| 101 California Street shooting | |

|---|---|

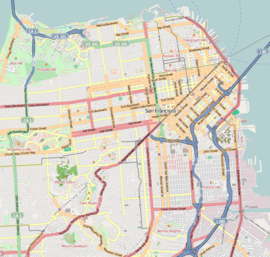

| Location | San Francisco, California, US |

| Coordinates | 37°47′34″N 122°24′00″W / 37.7928336°N 122.4000693°W |

| Date | July 1, 1993 2:57 p.m. |

Attack type | |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 10 (including the perpetrator and a victim who died in 1995) |

| Injured | 5 |

| Perpetrator | Gian Luigi Ferri |

| Motive | Undetermined |

The 101 California Street shooting was a mass shooting on July 1, 1993, in San Francisco, California, United States. The killings sparked a number of legal and legislative actions that were precursors to the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, H.R. 3355, 103rd Congress. The Act took effect in 1994 and expired in September 2004 after the expiration of a sunset provision. At the time, the incident was the deadliest mass shooting in the Bay Area's history, being surpassed 28 years later by the 2021 San Jose shooting.[1]

Shootings

[edit]At 2:57 p.m. 55-year-old failed entrepreneur[2] Gian Luigi Ferri (born December 29, 1937, as Gianluigi Ettore Ferri) entered an office building at 101 California Street in San Francisco and made his way to the offices of the law firm Pettit & Martin on the 34th floor. Ferri's reason for targeting that particular firm is unknown, though Ferri had just weeks earlier expressed his strong grudge against lawyers in general when asked by Los Angeles barber Keith Blum, "If you were locked in a room with Saddam, the Ayatollah Khomeini and a lawyer, and you had a gun with two bullets in it, who would you shoot?" Ferri, who had heard the gag before, replied, "The lawyer—twice."[2] P&M had redirected him to alternative legal counsel about some real estate deals in the Midwest in 1981, and had no contact with him in the 12 years since they could not advise him on matters out of state. After exiting an elevator, Ferri donned a pair of ear protectors and opened fire with a pair of TEC-9 handguns and a .45-caliber semiautomatic handgun.[2] He reportedly used a mix of Black Talon hollow point and standard ammunition and used Hell-Fire trigger systems for the TEC-9 pistols. After roaming the 34th floor, he moved down one floor through an internal staircase and continued shooting. The attack continued on several floors before Ferri committed suicide as San Francisco Police closed in. Eight people were killed in the attack, and six others injured.[3]

The reason for the shootings was never fully determined. A typed letter left behind by Ferri contained a list of complaints,[4] but the letter was largely unintelligible. Four single spaced pages in length, the letter contained many grammatical errors, misspellings and was typed in all caps.[5] Ferri claimed he had been poisoned by monosodium glutamate (MSG), a flavor enhancer in food, and that he had been "raped" by Pettit & Martin and other firms. The letter also contained complaints against the Food and Drug Administration, the legal profession, and a list of over 30 "criminals, rapists, racketeeres [sic], lobbyists", none of whom were among his actual victims.[6] Pettit & Martin occupied floors 33 (partial floor) and 34 through 36. The main reception floor was 35 and Ferri intended that floor as a target. His elevator stopped at the 34th floor because a secretary from that floor had pushed the up button for an elevator. As a result, Ferri began shooting on the 34th floor and worked his way down to lower floors.

Victims

[edit]Killed

[edit]- Shirley Mooser, 64, was a secretary at the Trust Company of the West, which had offices at 101 California Street.

- Allen J. Berk, 52, was a partner at Pettit & Martin, experienced in labor law, and was well-respected in the San Francisco legal community. He earned an undergraduate degree from City University of New York, and received his law degree from George Washington University.

- Donald "Mike" Merrill, 48, was an employee of the Trust Company of the West, which had offices at 101 California Street. He had worked as an energy industry consultant, working with independent energy projects.

- Jack Berman, 36, was a partner with the firm Bronson, Bronson, & McKinnon who was at Pettit & Martin's offices to attend a deposition of his client Jody Sposato. Both attorney Berman and his client were killed. A president of the American Jewish Congress known for his work specializing in employment law and chairing the firm's pro bono committee, Berman was born in Moosup, Connecticut, and graduated from Brown University before receiving his law degree from Boston University School of Law. Berman also co-founded TAX-AID,[7] an organization that provides free income tax preparation, and the San Francisco Transitional Housing Fund, a program to aid homeless individuals in finding housing. The New Lawyers Section of the California Lawyers Association gives an annual award in Berman's name.[8]

- Deborah Fogel, 33, was a legal secretary for the law firm of Davis Wright Tremaine, which had offices at 101 California Street.

- Jody Jones Sposato, 30, was a young mother and a client of Bronson, Bronson & McKinnon. She was the plaintiff in a sex discrimination lawsuit against her employer, Electronic Data Systems Corporation. She was at Pettit & Martin for a second day of deposition, accompanied by her attorney Jack Berman.

- David Sutcliffe, 30, was a law student at the University of Colorado Law School who was interning at Pettit & Martin for the summer.

- John Scully, 28, was a lawyer with Pettit & Martin who died, according to news reports, while protecting his wife from the gunman. Interested in labor law, Scully earned his bachelor's degree from Gonzaga University and his law degree at the University of San Francisco. He had gotten married about a year before the shootings, and many of his colleagues had attended his wedding in Hawaii. His new wife was visiting the firm for lunch when the gunman arrived. Scully pushed his wife underneath the desk, shielding her with his own body.

Injured

[edit]- Victoria Smith, 41.

- Sharon Jones O'Roke, 35, was in-house counsel at Electronic Data Systems Corporation in Dallas, Texas, and was using a Pettit & Martin conference room to take the deposition of Jody B. Jones Sposato. O'Roke was the first one shot during the attack.

- Michelle Scully, 27.

- Brian F. Berger, 39, who died two years later in 1995, at age 41, at his home from unknown and undisclosed causes, possibly from his "severe" wounds that he sustained to his arm and chest during the 1993 shooting.[1] In 1997, in was publically confirmed that he had died from wounds sustained in the shooting.[9]

- Deanna Eaves, 33, a court reporter recording the deposition of Jody Jones Sposato.

- Charles Ross, 42.

Reaction

[edit]The shootings spurred calls for tighter gun control and were followed by a number of legal and legislative actions. California implemented some of the toughest gun laws in the United States.[10]

A number of organizations were formed in the wake of the shootings, including Legal Community Against Violence,[11] which acts as a resource for information on federal, state, and local firearms policies. The American Jewish Congress founded the Jack Berman Advocacy Center[12] to lobby and organize with regard to gun control and violence reduction.

At the time of the attack, the law firm of Pettit & Martin were already on the decline, and the attack was a brutal blow to the struggling firm. After the defections of several partners, the firm dissolved in 1995.[13]

See also

[edit]- List of rampage killers in the United States

- List of homicides in California

- Federal assault weapons ban

- Gun politics in the United States

- Hollow-point bullet

- Wakefield massacre

References

[edit]- ^ a b Woolfolk, John (May 26, 2021). "The Bay Area's deadliest mass shootings". The Mercury News. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Lambert, Pam (July 19, 1993). "Falling Down". People. Dotdash Meredith. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 19, 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 21, 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "San Francisco Gunman's Rage Is Revealed in Four-page Letter". Chicago Tribune. July 4, 1993. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ^ "Seeking Motive in the Killing of 8: Insane Ramblings Are Little Help" Archived March 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times (4 July 1993).

- ^ High-quality tax return preparation for Bay Area families Archived July 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Tax Aid (31 October 2012).

- ^ "Jack Berman Award of Achievement". The State Bar of California. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ Chao, Julie (July 2, 1997). "Relatives recall loved ones lost at 101 California St". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ Harriet Chiang (July 1, 2003). "10 Years After: 101 California Massacre Victims Helped Toughen Gun Laws". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ Visit Our New Site! Archived April 24, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Lcav.org.

- ^ National Special Interest Groups - Project Vote Smart Archived May 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Vote-smart.org.

- ^ [1] Archived February 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine SFGate.com.

External links

[edit]- j.weekly article about the shootings

- z Publishing aggregation of news articles about the shootings

- Victims of Chance in Deadly Rampage, The New York Times (7 July 1993)

- The Broker Who Killed 8: Gunman's Motives a Puzzle, The New York Times (3 July 1993)

- Seeking Motive in the Killing of 8: Insane Ramblings Are Little Help, The New York Times (4 July 1993)

- Suit Can Proceed Against Maker Of Guns Used in 1993 Killings, The New York Times (12 April 1995)

- S.F. Gunman's Firm Failing, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (3 July 1993)

- Gunman kills 8 and Commits Suicide, Kingman Daily Miner (2 July 1993)

- Murder in Calif.: What price fame?, St. Petersburg Times (6 July 1993)