| Part of a series on |

| Islam in Australia |

|---|

|

| History |

|

| Mosques |

| Organisations |

| Islamic organisations in Australia |

| Groups |

| Events |

| National Mosque Open Day |

| People |

Afghan cameleers in Australia, also known as "Afghans" (Pashto: افغانان) or "Ghans" (Pashto: غانز), were camel drivers who worked in Outback Australia from the 1860s to the 1930s. Small groups of cameleers were shipped in and out of Australia at three-year intervals, to service the Australian inland pastoral industry by carting goods and transporting wool bales by camel trains. They were commonly referred to as "Afghans", even though the majority of them originated from the far western parts of British India, primarily the North-West Frontier Province and Balochistan (now Pakistan), which was inhabited by ethnic Pashtuns (historically known as Afghans) and Balochs. Nonetheless, many were from Afghanistan itself as well. In addition, there were also some with origins in Egypt and Turkey.[1] The majority of cameleers, including cameleers from British India, were Muslim, while a sizeable minority were Sikhs from the Punjab region. They set up camel-breeding stations and rest-house outposts, known as caravanserai, throughout inland Australia, creating a permanent link between the coastal cities and the remote cattle and sheep grazing stations until about the 1930s, when they were largely replaced by the automobile.[1] They provided vital support to exploration, communications and settlement in the arid interior of the country where the climate was too harsh for horses. They also played a major role in establishing Islam in Australia, building the country's first mosque at Marree in South Australia in 1861, the Central Adelaide Mosque (the first permanent mosque in Adelaide, still in use today), and several mosques in Western Australia.

Many of the cameleers and their families later returned to their homelands, but many remained and turned to other trades and ways of making a living. Today, many people can trace their ancestry back to the early cameleers, many of whom intermarried with local Aboriginal women and European women in outback Australia.

History

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]The various colonies of Australia being under the dominion of the British Empire, the early settlers used people from British territories, particularly Asia, as navigators. In 1838, Joseph Bruce and John Gleeson brought out 18 of the first "Afghans", who arrived in the colony of South Australia in 1838. The first camel, which became known as "Harry", arrived at Port Adelaide in 1840 and was used in an 1846 expedition by John Horrocks. It proved its worth as a pack animal,[2] but unfortunately caused Horrocks's death by accidental shooting so was later put down.[3][2][4]

Camels had been used successfully in desert exploration in other parts of the world, but by 1859, only seven camels had been imported into Australia.[5] In 1858 George James Landells, who was known for exporting horses to India, was commissioned by the Victorian Exploration Committee to buy camels and recruit camel drivers.[5][6] Eight (or three[7]) cameleers arrived in Melbourne from Karachi on the ship Chinsurah on 9 June 1860 with a shipment of 24 camels for the Burke and Wills expedition.[8][2] In 1866 Samuel Stuckey went to Karachi, and imported more than 100 camels as well as 31 men. In the 1860s, about 3,000 camel drivers came to Australia from Afghanistan and the Indian sub-continent, along with more camels.[4]

Although the cameleers came from different ethnic groups and a range of regions – mostly Baluchistan, Kashmir, Sind and Punjab (parts of present-day Pakistan, Afghanistan, north-western India and eastern Iran), with a few from Egypt and Turkey, they were known collectively as Afghans, later shortened to "Ghans".[4] Ethnic groups included Pashtun, Punjabi, Baloch (or Baluch) and Sindhis (from the region between the southern Hindu Kush in Afghanistan and the Indus River in what is now Pakistan)[9] as well as others (fewer in number) from Kashmir, Rajasthan, Egypt, Persia and Turkey.[2] Most practised Islam, and many blended this with their local customs, in particular the Pashtun code of honour.[10]

Use of camels

[edit]Before the building of railways and the widespread adoption of motor vehicles, camels were the primary means of transporting goods in the Outback, where the climate was too harsh for horses and other beasts of burden. From 1850 to 1900, the cameleers played an important part in opening up Central Australia, helping to build the Australian Overland Telegraph Line between Adelaide and Darwin and also the railways. The camels hauled the supplies and their handlers erected fences, acted as guides for several major expeditions, and supplied almost every inland mine or station with its goods and services.[3]

The majority of cameleers arrived in Australia alone, leaving wives and families behind, to work on three-year contracts. Those who were not given living quarters on a station (such as on Thomas Elder's Beltana),[2] generally lived away from white populations, at first in camps, and later in "Ghantowns" near existing settlements. A thriving Afghan community lived at Marree, South Australia (then also known as Hergott Springs) leading to the nicknames "Little Asia" or "Little Afghanistan". When rail reached Oodnadatta, the caravans travelled between there and Alice Springs (formerly known as Stuart).[3] There were caravanserais for the camel caravans travelling from Queensland, New South Wales and Alice Springs.[6] There was more acceptance by the local Aboriginal people, and some cameleers married local Aboriginal women and started families in Australia.[2] However some married European women, and writer Ernestine Hill wrote of white women who had joined the Afghan community and converted to Islam, even making the pilgrimage to Mecca.[3]

In 1873 Mahomet Saleh accompanied explorer Peter Warburton to Western Australia. Three Afghans helped William Christie Gosse to find a way from the Finke River to Perth. Two years later Saleh assisted Ernest Giles on an expedition, and J.W. Lewis used camels when surveying the country north-east of Lake Eyre in 1874 and 1875.[3]

In the 1880s, camels were used by police in northern South Australia for the collection of statistics and census forms as well as other kinds of work, and the Marree police used camels on patrol until 1949.[3] At Finke/Aputula, just over the border in the Northern Territory, the last camel police patrol was in 1953.[11]

In the 1890s, camels were used extensively in the Western Australian Goldfields to transport food, water, machinery and other supplies. In 1898 there were 300 Muslims in Coolgardie.[6]

During the Federation Drought, which devastated eastern Australia from 1895 to 1902, the camels and their drivers were indispensable. John Edwards wrote to the Attorney-General in 1902: "It is no exaggeration to say that if it had not been for the Afghan and his camels, Wilcannia, White Cliffs, Tibooburra, Milperinka and other towns...would have practically ceased to exist".[6]

Success and discrimination

[edit]By the turn of the century, Muslim entrepreneurs dominated the camel business, including Fuzzly Ahmed (Port Augusta–Oodnadatta, then Broken Hill) and Faiz Mahomet (Marree and Coolgardie). Abdul Wade (also known as Wadi, Wabed, Wahid) was especially successful in New South Wales, and bought and set up the Wangamanna station as a camel breeding and carrying business. He married the widow Emily Ozadelle and they had seven children. Wade worked hard at fitting in and being seen as an equal to his Australian peers, dressing in the European style, educating his children at top private schools and becoming a naturalised citizen. However his attempts were ridiculed and at the end of the camel era, he sold up and returned to Afghanistan.[2] By 1901, there were an estimated 2000–4000 cameleers in Australia. Many of them made regular trips home to deal with family matters.[6]

While outback settlers, farmers and others who had dealings with the Afghans often vouched for them, finding that they held many values in common, prejudice arose and discriminatory legislation was introduced by colonial, state and federal governments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One example was a 1895 law which prevented Afghans from mining on the Western Australia goldfields, after tensions arose between the communities and Afghans were accused of polluting waterholes (although no evidence was ever found for this).[6][2] In The Ballad of Abdul Wade (2022), author Ryan Butta tells of how Abdul Wade was attacked by people who saw him as a threat to their business interests, despite his contributions to the community, including offering hundreds of his camels to add to Australia's contribution to World War I in 1914. Cameleers saved Cunnamulla residents from "semi-starvation" after floods cut the town off from all other modes of transport in 1890. Yet in 1892, The Bulletin published an editorial saying "the imported Asiatic... is another cheap labour curse in a land where such curses are already much too plentiful".[12][13]

Many cameleers were refused naturalisation and found themselves refused entry when they tried to return to Australia after visits home, based on the Immigration Restriction Act 1901. In 1903 a petition was raised about a number of discriminatory practices, but nothing came of it.[2]

The last of the cameleers

[edit]Through the 1930s and 1940s, with no employment and sometimes a hostile community, many cameleers returned to their homelands, but others remained and developed trades and other means of making a living. In 1952, a small number of "ancient, turbaned men," supposedly as old as 117, were to be found at the Adelaide mosque.[2]

It is recorded that the first person to make a deposit, his life savings of £29, in the newly-formed Savings Bank of South Australia on 11 March 1848 was "an Afghan shepherd", with his name recorded as "Croppo Sing".[14]

Impact and legacy

[edit]From the mid 1800s through to the early 1900s, camels and cameleers were significant contributors to the wool industry, the mining industry, the construction of the Overland Telegraph and the rabbit-proof fence, and transporting water to wherever it was needed.[12] However, even though the Afghans' help was greatly appreciated, they were also subject to discrimination because of their religion and appearance, and because of the competition they provided to European bullock (ox)[2] and horse teamsters.[12] Many of the European competitors were also cameleers, and in 1903 a European camel train owner in Wilcannia replaced all of his Afghan camel drivers with Europeans.[15]

Author Ryan Butta has highlighted the fact that the cameleers were rendered invisible in some of the popular mythologies and histories of Australia, such as Banjo Paterson's work. Paterson spent time in Bourke at the time the cameleers were an active part of the community and business there, yet did not write about them.[12]

Australia's most famous train, The Ghan, was named a century ago but not in homage to outback cameleers as popular folklore would have it. The antiquated passenger train that ran on the narrow-gauge Central Australia Railway between Port Augusta and Alice Springs – a service that ended in 1980 – was nicknamed "The Afghan Express" by a railwayman at Quorn in 1923: he was observing a Moslem man running to a place of quiet for evening prayers during a brief stop there. Soon the name was shortened to The Ghan and passed into public use, although the term was never used by the railway administration. In the 1960s a Commonwealth Railways marketer decided that the name recognised Afghan cameleers for their contribution to outback transport. The idea was his fiction, but it stuck. Marketing of the present-day Ghan between Adelaide and Darwin is still focused on the same sentiment, compelling as it is.[16]

Many camels were shot by police after they were superseded by modern transport, but some cameleers released their camels into the wild rather than allow them to be shot. A large population of feral camels remains from that time.[3]

Date palms, planted wherever the Afghans went, are another legacy of the cameleers.[3] Another, understudied, legacy of the cameleers is the traces of Sufism introduced across Australia, evident in the remaining artefacts, particularly prayer beads, some books, and letters belonging to the cameleers.[17][18]

Descendants

[edit]A fourth-generation descendant of a Baluch cameleer who settled in Geraldton, Western Australia, set up a sheep station and married an Aboriginal woman, is proud of her heritage on both sides. She says that it was difficult for her ancestor to acquire permanent residence and permission to marry, but the Afghans were honourable men who preferred to marry rather than rape local women.[19]

Several descendants in Adelaide formed the Australian Outback Afghan Camelmen Descendants and Friends Memorial Committee, which organised a memorial in 2007. They included Janice Taverner (née Mahomet), Mona Wilson (née Akbar), Eric Sultan, Abdul Bejah (son of Jack Bejah and grandson of Dervish Bejah), Lil Hassan (née Fazulla), and Don Aziz.[20]

Marree still has the longest-surviving "Ghantown", and many descendants of the original cameleers still live there.[21]

Memorials

[edit]There is a memorial at Whitmore Square, Adelaide which pays homage to the city's Afghan camel drivers,[22] called Voyagers and created by South Australian artist Shaun Kirby and his company Thylacine Art Projects. It was unveiled on the night of 11 December 2007, so that the lighting of the sculpture could be appreciated. It is in the shape of a crescent, evocative of sand dunes in the deserts of South Australia as well as the Hilal (crescent moon) associated with Islam. The curved wall is covered with handmade rippled tiles, produced at the JamFactory. There is a red metalwork decorative screen with traditional Islamic patterning on the front of the crescent. The memorial does not have a plaque, but there is a small stone obelisk in front of the crescent wall with Arabic writing.[20][23][24]

There is also a bronze plaque honouring Bejah Dervish on the Jubilee 150 Walkway on North Terrace. It reads "Dervish Bejah, c1862-1957, Camel-driver, explorer".[25]

A commemorative plaque for Faiz and Tagh Mahomet on St Georges Terrace in Perth acknowledges their contributions as camel owners and drivers in the 1890s in opening up the interior of Western Australia before the building of the railway.[26]

In film

[edit]- A 2020 documentary, The Afghan Cameleers in Australia, directed by Afghan/Australian filmmaker Fahim Hashimy, explores and records the relationships that many cameleers formed with Aboriginal women, and their descendants.[27]

- The 2020 drama feature film, The Furnace is set during the gold rushes in Western Australia and highlights the roles of Afghan cameleers.[28][29][30]

- Watandar, My Countryman is a documentary film directed by Jolyon Hoff and co-written and co-produced by Hazara photographer Muzafar Ali,[31] who arrived in Australia as a refugee in 2015. The film, which explores the concept of identity, arose after Ali started investigating the long history of Afghan people in Australia.[32] It premiered at the Adelaide Film Festival in October 2022.[33] The film features Nici Cumpston, artistic director of Tarnanthi, and curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the Art Gallery of South Australia.[34]

Mosques

[edit]

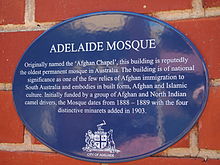

in Little Gilbert Street, Adelaide

At first a special room set aside in someone's house served as places of prayer, but as time went on, the Muslim communities wanted to have dedicated places of worship. At Marree, an important junction of the camel trade, the Afghan cameleers built the earliest mosque in Australia in 1861,[2] a simple mud and tin-roofed building,[6] but this subsequently fell into disuse and was demolished.[35]

Over time, as some members of the Afghan community prospered through trade and camel breeding, they contributed towards the building of the oldest permanent mosque in Australia, the Central Adelaide Mosque in 1888–89.[35]

The Perth Mosque, which dates from 1905,[36] was paid for by fund-raising efforts throughout the WA Muslim community, much of it instigated by the highly educated businessman Mohamed Hasan Musakhan (also known as Hassan Musa Khan) and the cameleer Faiz Mahomet.[37] In 1910 there were also mosques in Coolgardie, Mount Malcolm, Leonora, Bummers Creek, Mount Sir Samuel and Mount Magnet (all in WA).[6]

Notable people

[edit]- Dervish Bejah (or Bejah Dervish) (c.1862 – 1957), who had been decorated for his military service, led his community in Marree. He came from Baluchistan, and later took part with Lawrence Wells in the Calvert Expedition of 1896.[3] He is commemorated by a plaque in the Jubilee 150 Walkway in Adelaide.

- Dost Mahomed (c.1825 – c.1885), son of Mulla Mohamed Jullah of Gaznee, was a Pashtun who had served as a sepoy in the British Indian Army. Recruited by Landells for the Burke and Wills expedition, he was one of the first eight cameleers who arrived in Melbourne from Karachi on the ship Chinsurah on 9 June 1860 and the oldest cameleer in the party. He went with Burke from Menindee to Cooper Creek, where he waited with William Brahe's party, helping to feed them with ducks and fish. He also participated in Howitt's Victorian Relief Expedition, to recover the bodies of Burke and Wills, and it was during this journey that he was bitten badly by a bull camel, causing him loss of use of his right arm. He then worked in a market garden in Menindee, dying in the early 1880s.[8]

- Dost Mahomet (c.1873 – 1909) was a Baloch cameleer who worked the WA goldfields in the late 1890s.

- There was also Dost Mahomed (b.1878, Baluchistan) who worked at Port Hedland in 1904, and Dost Mahomed (b.1881, India) who arrived in Australia in 1898 and returned home several times between 1914 and 1931.[8]

- Faiz Mahomet (c.1848 – 1910) operated a camel station in South Australia, before opening camel stations in a number of locations in Western Australia in partnership with his brother Tagh. He assisted in raising funds for the construction of the Perth Mosque and laid its foundation stone on 13 November 1905.[38]

- Gool Mohomet or Gul Muhammed (1865–1950), who married Frenchwoman Adrienne Lesire, owned a station and later became Imam at Adelaide Mosque.[39]

- Haji Mulla Merban came from Kandahar to Port Darwin in the early days. He became a leader of the camel drivers working for the Overland Telegraph Line, eventually settling in Adelaide. He married a European woman and was known as a peace maker, once settling a dispute between Abdul Wade and Gunny Khan, two wealthy camel owners. He also became the first mullah (spiritual leader) of the Afghan community in SA at the Adelaide Mosque. He was buried at Coolgardie in 1897.[3]

- Hassan Musa Khan (30 May 1863 – 1939), well-educated and multi-lingual, ran a bookshop, founded the Perth Mosque and later lived in Adelaide.

- Mahomet Allum (c.1858 – 1964), herbalist and philanthropist, who settled in Adelaide and became known as "the wonder man".[6][40]

- Monga Khan (c.1870 – 1930) was a "licensed hawker" of imported goods based in Victoria.[41] According to research by Len Kenna, Khan was originally from Bathroi, a village in Dadyal Tehsil, Mirpur, Azad Kashmir.[42] His 1916 portrait (as recorded in the National Archives of Australia) was used in 2016 by Australian artist Peter Drew to create a poster campaign called "Real Aussies Say Welcome".[43] This project was followed by the book and ebook "The Legend of Monga Khan: An Aussie Folk Hero", which includes illustrations, poems and short stories.[44][45]

- Mullah Abdullah (c.1855 – 1 January 1915), one of two perpetrators of an attack known as the Battle of Broken Hill in 1915, in which the former cameleers shot four people dead and wounded seven more, before being killed themselves. The other man was Gool Badsha Mahomed, not to be confused with Gool Mohomet of Adelaide below.

- Abdul Kadir was the leader of the community in Oodnadatta.[3]

- Abdul Wade, a young Afghan man who brought his camels to the outback in the 1890s[12]

- Fuzzly Ahmed (Port Augusta–Oodnadatta, then Broken Hill)[2]

- Hector Mahomet, Peer Mahomet and Charlie Sadadeen were well known on the Oodnadatta track.[3]

Jones (2007) has "A biographical listing of Australia's Muslim cameleers" (which includes Sikhs), representing "more than half of the total number of cameleers and other Muslim men from south Asia who worked in Australia during the era of camel transport", on pages 166–191.[8]

See also

[edit]- Afghan Australian

- Afghan Rock, a place in WA where two cameleers were shot and killed

- Ahmadiyya in Australia

- Battle of Broken Hill

- Demography of Afghanistan

- Indian Australians

- Pakistani Australians

- Islam in Australia

- Non-resident Indian and person of Indian origin

- Pashtun diaspora

- United States Camel Corps

References

[edit]- ^ a b Afghan cameleers in Australia. 3rd September 2009. Australia.gov.au. Archived 5 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Afghan cameleers in Australia". australia.gov.au. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Afghan camelmen". South Australian History: Flinders Ranges Research. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Faris, Nezar (December 2012). "Contextualisation and Conceptualisation in a multifarious context: Mixed models of leadership" (PDF). Paper presented at ANZAM conference held in Perth in 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Camels & Sepoys for the Expedition". Burkeandwills.net.au. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Stories: Cameleers and hawkers". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Note: Conflicting sources.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Philip G.; Jones, Anna (2007). Australia's Muslim Cameleers: Pioneers of the Inland, 1860s-1930s (Pbk ed.). Wakefield Press. p. 39,172. ISBN 9781862547780.

- ^ Westrip, J.; Holroyde, P. (2010). Colonial Cousins: a surprising history of connections between India and Australia. Wakefield Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-1862548411.

- ^ Jones, Philip G.; Jones, Anna (2007). Australia's Muslim Cameleers: Pioneers of the Inland, 1860s-1930s (Pbk ed.). Wakefield Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9781862547780.

- ^ Kelham, Megg (November 2010). "A Museum in Finke: An Aputula Heritage Project" (PDF). pp. 1–97. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019. See Territory Stories for details of document

- ^ a b c d e Kelsey-Sugg, Anna (2 August 2022). "Ryan Butta says Afghan cameleers were ignored by Henry Lawson, and our national story is the poorer for it". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "The Ballad of Abdul Wade". Affirm Press. 26 July 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Our Story". BankSA. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ National Advocate newspaper, 17 April 1903, page 2.

- ^ Barrington, Rodney, ed. (2024). Into the Pass: a history of Pichi Richi Railway. Quorn, South Australia: Pichi Richi Railway Preservation Society Inc. p. 20. ISBN 9781763538726.

- ^ Cook, Abu Bakr Sirajuddin (2018). "Tasawwuf 'Usturaliya". Australian Journal of Islamic Studies. 3 (3): 60–74. doi:10.55831/ajis.v3i3.119. ISSN 2207-4414. S2CID 248537054.

- ^ Cook, Abu Bakr Sirajuddin; Dawood, Rami (18 March 2022). "On the History of Sufism in Australia: a manuscript from the Broken Hill Mosque". Journal of Sufi Studies. 11 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1163/22105956-bja10021. ISSN 2210-5948.

- ^ Mohabbat, Besmillah (1 June 2019). "Meet the fourth generation of a Baluch Afghan cameleer". SBS. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ a b Elton, Jude. "Voyagers". Adelaidia. History Trust of South Australia. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Stevens, Christine (27 July 2011). "Australia's Afghan cameleers". Australian Geographic. Originally published in the Oct-Dec issue, AG#20.

- ^ Affifudin, Amirul Husni (September 2018). "Historical Archaeology Report: Mahomet Allum Khan". ResearchGate: 27–29. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.23125.27365. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ "Afghan cameleers memorial" (photo). State Library of South Australia. 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Afghan Cameleers". Monument Australia. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "J150 Plaque, Bejah Dervish". Adelaidia. History Trust of South Australia. 1 February 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Discover Multicultural Perth" (PDF). Office of Multicultural Interests.

- ^ Mohabbat, Besmillah (13 November 2020). "Filmmaker explores the love that grew between Afghan cameleers and Indigenous women". SBS Language. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Australian feature film shines light on pioneering gold rush cameleers". Gold Industry Group. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Bakare, Lanre (8 September 2020). "The Furnace director: stories of Australia's cameleers 'felt like a huge historic omission'". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Singh, Manpreet K. (9 December 2020). "'Confronting truths': Film peels back layers of 'untold history' of migrant cameleers in Australia". SBS Language. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Watandar, My Countryman at IMDb

- ^ "Former Hazara refugee and photographer connects with cameleer descendants in Australian outback". ABC News. 21 January 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Watandar, My Countryman". Adelaide Film Festival. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Home page". Watandar, My Countryman. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Weekend Notes: Adelaide City Afghan Mosque". Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Westrip, J.; Holroyde, P. (2010). Colonial Cousins: a surprising history of connections between India and Australia. Wakefield Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-1862548411.

- ^ "inHerit – State Heritage Office". inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Koutsoukis, A. J., "Mahomet, Faiz (1848–1910)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 25 April 2022

- ^ "The Gool Mahomet story". Farina Restoration Project. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Hankel, Valmai A. (1968). "Allum, Mahomet (1858–1964)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 7. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Hashmi, Zushan (13 June 2016). "How The 'Afghan Cameleer' Campaign Accidentally Hides Diversity". The New Matilda. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Jordan, Crystal; Kenna, Len (2016). "The Legend of Monga Khan. No! The True Story". Australian Indian Historical Society Inc. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Drew, Peter (2016). "'Aussie' poster designed by Peter Drew". Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences Australia. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "The Legend of Monga Khan, an Aussie folk hero". The Boroughs. 12 March 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Drew, Peter; Kurmelovs, Royce, eds. (2016), The legend of Monga Khan: an Aussie folk hero, Peter Drew Arts, ISBN 978-0-9954388-0-4

Further reading

[edit]- Lerwill, Ben (10 April 2018). "The strange story of Australia's wild camel". BBC.

- Lee, Tim (29 March 2020). "Immigrant who fought White Australia policy for right to vote leaves lasting legacy". ABC News. Retrieved 1 April 2020. – Story of Sikh hawker Siva Singh.

- Snow, Madison (1 February 2020). "Forgotten history of Australia's exotic cameleers revived by living relatives". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. – Cameleers in Western Australia.

- Jones, Philip G.; Jones, Anna (2007). Australia's Muslim Cameleers: Pioneers of the Inland, 1860s-1930s (Pbk ed.). Wakefield Press. ISBN 9781862547780. (Online version of 2010 ed. at Google Books includes short biographies of a large number of cameleers.)

- Stevens, Christine (2003) [1989]. Tin Mosques and Ghan Towns: A History of Afghan Camel Drivers in Australia. ISBN 0-9581760-0-0.

- Stevens, Christine (27 July 2011). "Australia's Afghan cameleers". Australian Geographic.

- "Australian Muslim cameleers". Government of South Australia, South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014.

- "Afghan Cameleers of Australia". Geni. Many names and further information.

- "Afghan handlers and camels". State Library of South Australia. SA Memory. Photo with information and bibliography.

- Bibliography on Camels and Cameleers at the Northern Territory Library.

- The Afghan Camelmen (South Australian History: Flinders Ranges Research).

- Afghan Cameleers (ABC TV broadcast transcript, 1 November 2004 – George Negus).

- Pioneering Afghans from Bushmag.

- Cook, Abu Bakr Sirajuddin (2023). "Mullah Abdullah, A mullah? A reassessment of the assertions and the evidence". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs.