| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

African American newspapers (also known as the Black press or Black newspapers) are news publications in the United States serving African American communities. Samuel Cornish and John Brown Russwurm started the first African American periodical, Freedom's Journal, in 1827. During the antebellum period, other African American newspapers sprang up, such as The North Star, founded in 1847 by Frederick Douglass.

As African Americans moved to urban centers beginning during the Reconstruction era, virtually every large city with a significant African American population had newspapers directed towards African Americans. These newspapers gained audiences outside African American circles. Demographic changes continued with the Great Migration from southern states to northern states from 1910 to 1930 and during the Second Great Migration from 1941 to 1970. In the 21st century, papers (like newspapers of all sorts) have shut down, merged, or shrunk in response to the dominance of the Internet in terms of providing free news and information, and providing cheap advertising.[1][2]

History

[edit]

Origins

[edit]Most of the early African American publications, such as Freedom's Journal, were published in the North and then distributed, often covertly, to African Americans throughout the country.[3] The newspaper often covered regional, national, and international news. It also addressed the issues of American slavery and The American Colonization Society which involved the repatriation of free blacks back to Africa.[4]

19th century

[edit]Some notable black newspapers of the 19th century were Freedom's Journal (1827–1829), Philip Alexander Bell's Colored American (1837–1841), the North Star (1847–1860), the National Era, The Aliened American in Cleveland (1853–1855), Frederick Douglass' Paper (1851–1863), the Douglass Monthly (1859–1863), The People's Advocate, founded by John Wesley Cromwell and Travers Benjamin Pinn (1876–1891), and The Christian Recorder (1861–1902).[5]

In the 1860s, the newspapers The Elevator and the Pacific Appeal emerged in California as a result of black participation in the Gold Rush.[6] The American Freedman was a New York-based paper that served as an outlet to inspire African Americans to use the Reconstruction era as a time for social and political advancement. This newspaper did so by publishing articles that referenced African American mobilization during that era that had not only local support but had gained support from the global community as well.[citation needed] The name The Colored Citizen was used by various newspapers established in the 1860s and later.

In 1885, Daniel Rudd formed the Ohio Tribune, said to be the first newspaper "printed by and for Black Americans", which he later expanded into the American Catholic Tribune, purported to the first Black-owned national newspaper.[7] The Cleveland Gazette was established in the 1880s and continued for decades.

The National Afro-American Press Association was formed in 1890 in Indianapolis, Indiana.[8][9]

In 1894, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin founded The Woman's Era, the first nationally distributed newspaper published by and for African American women in the United States.[10][11] The Woman's Era began as the official publication of the National Association of Colored Women, and grew in import and impact with the founding of the National Federation of Afro American Women in 1895. It was also one of the first newspapers, along with the National Association Notes, to create journalism career opportunities for Southern black women.[12]

Many African American newspapers struggled to keep their circulation going due to the low rate of literacy among African Americans. Many freed African Americans had low incomes and could not afford to purchase subscriptions but shared the publications with one another.[13]

20th century

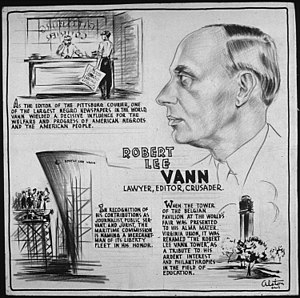

[edit]African American newspapers flourished in the major cities, with publishers playing a major role in politics and business affairs. By the 20th century, daily papers appeared in Norfolk, Chicago, Baltimore and Washington, D.C.[14] Representative leaders included Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1870–1940) and John H. Sengstacke (1912–1997), publishers of the Chicago Defender; John Mitchell Jr. (1863–1929), editor of the Richmond Planet and president of the National Afro-American Press Association; Anthony Overton (1865–1946), publisher of the Chicago Bee; Garth C. Reeves Sr. (1919–2019), publisher emeritus of the Miami Times; and Robert Lee Vann (1879–1940), the publisher and editor of the Pittsburgh Courier.[15] In the 1940s, the number of newspapers grew from 150 to 250.[16]

From 1881 to 1909, the National Colored Press Association (American Press Association) operated as a trade association. The National Negro Business League-affiliated National Negro Press Association filled that role from 1909 to 1939.[17] The Chicago-based Associated Negro Press (1919–1964) was a subscription news agency "with correspondents and stringers in all major centers of black population".[18] In 1940, Sengstacke led African American newspaper publishers in forming the trade association known in the 21st century as the National Newspaper Publishers Association.[19]

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Black southern press both aided and, to an extent, hindered the equal payment movement of Black teachers in the southern United States. Newspaper coverage of the movement served to publicize the cause. However, the way in which the movement was portrayed, and those whose struggles were highlighted in the press, displaced Black women to the background of a movement they spearheaded. A woman's issue, and a Black woman's issue, was being covered by the press. However, reporting diminished the roles of the women fighting for teacher salary equalization and “diminished the presence of the teachers’ salary equalization fight” in national debates over equality in education.[20]

There were many specialized black publications, such as those of Marcus Garvey and John H. Johnson. These men broke a wall that let black people into society. The Roanoke Tribune was founded in 1939 by Fleming Alexander, and recently celebrated its 75th anniversary. The Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder is Minnesota's oldest black-owned newspaper[21] and one of the United States' oldest ongoing minority publication, second only to The Jewish World.[citation needed]

21st century

[edit]Many Black newspapers that began publishing in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s went out of business because they could not attract enough advertising. They were also victims of their own substantial efforts to eradicate racism and promote civil rights.[citation needed] As of 2002[update], about 200 Black newspapers remained. With the decline of print media and proliferation of internet access, more black news websites emerged, most notably Black Voice News, The Grio, The Root, and Black Voices.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Black-owned business

- List of African American newspapers and media outlets

- List of newspapers in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Arvarh E. Strickland and Robert E. Weems, eds. The African American Experience: An Historiographical and Bibliographical Guide (Greenwood, 2001), pp. 216–230. ISBN 978-0313298387

- ^ Simmons, Charles A. The African American press: a history of news coverage during national crises, with special reference to four black newspapers, 1827–1965. McFarland, 2006, p. 2. ISBN 978-0786403875

- ^ Bacon, Jacqueline (2003). "The History of Freedom's Journal: A Study in Empowerment and Community". The Journal of African American History. 88 (1): 1–20. doi:10.2307/3559045. JSTOR 3559045.

- ^ "Honoring African American Contributions: The Newspapers". 30 July 2020. Archived from the original on 2023-08-13. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ^ Knowlton, Steven. "LibGuides: African American Studies: Newspapers: 19th century". Libguides.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "History 313: Manual – Chapter 3". Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ^ "Daniel Rudd". Star Quest Production Network (SQPN). 2020-02-03. Archived from the original on 2020-06-11. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Nina Mjagkij, ed. (2001), Organizing Black America: an Encyclopedia of African American Associations, Garland, ISBN 978-0815323099

- ^ Gonzalez 2011.

- ^ Stabel, Meredith (2021). Radicals, Volume 2: Memoir, Essays, and Oratory: Audacious Writings by American Women, 1830-1930. University of Iowa Press. p. 173. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1m9x358. ISBN 978-1-60938-768-6. JSTOR j.ctv1m9x358.

- ^ "The Woman's Era". Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. Retrieved 2024-02-12 – via Lewis H. Beck Center at Emory University.

- ^ Wade-Gayles, Gloria (1981). "Black Women Journalists in the South, 1880-1905: An Approach to the Study of Black Women's History". Callaloo (11/13): 138–152. doi:10.2307/3043847. ISSN 0161-2492. JSTOR 3043847.

- ^ Rhodes, Jane (1998). Mary Ann Shadd Carry: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 120–123. ISBN 0253213509.

- ^ Jacqueline Bacon, Freedom's journal: the first African-American newspaper (2007).

- ^ Patrick S. Washburn, The African American Newspaper: Voice of Freedom (2006).

- ^ Mott, Frank Luther (1950). American Journalism: The history of newspapers in the United States 1690–1950. Macmillan. p. 794.

- ^ "National Colored Press Association". nkaa.uky.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ "Associated Negro Press", Encyclopedia of Chicago, Chicago Historical Society, archived from the original on June 8, 2008, retrieved March 20, 2017

- ^ Osgood, Harley (2018-09-30). "The National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) (1940– )". Black Past. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ Aiello, Thomas (February 2018). "'Do We Have Any Men to Follow in Her Footsteps?': The Black Southern Press and the Fight for Teacher Salary Equalization". History of Education Quarterly. 58 (1): 94–121. doi:10.1017/heq.2017.50. ISSN 0018-2680.

- ^ "About". Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

Further reading

[edit]- Bacon, Jacqueline. Freedom's journal: the first African-American newspaper (Lexington Books, 2007)

- Belles, A. Gilbert (1975). "The Black Press in Illinois". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984). 68 (4): 344–352. JSTOR 40191030. online

- Bradshaw, Katherine A.; Gibbons, Sheila; Bradshaw, Katherine A.; O'Reilly, Julie D.; Zacher, Dale; Myers, Cayce (2015). "Book Reviews". Journalism History. 41: 52–56. doi:10.1080/00947679.2015.12059122. Sub-article: Bradshaw, Katherine A. "Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press Archived 2019-05-02 at the Wayback Machine." Journalism History 41.1 (2015): 53+

- Brown, Warren Henry (1946). Check list of Negro newspapers in the United States (1827–1946). Jefferson City, Mo.: Lincoln University School of Journalism. OCLC 36983520.

- Bullock, Penelope L. The Afro-American Periodical Press, 1838–1909 (LSU Press, 1981).

- Buni, Andrew (1974). Robert L. Vann of the Pittsburgh courier: politics and Black journalism. University of Pittsburgh Press. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- Burma, John H. (1947). "An Analysis of the Present Negro Press". Social Forces. 26 (2): 172–180. doi:10.2307/2571774. JSTOR 2571774.

- Dann, Martin E. The Black Press, 1827–1890: The Quest for National Identity (1972).

- Davis, Ralph N. "The Negro Newspapers and the War." Sociology and Social Research 27 (1943): 378–380.

- Detweiler, Frederick German (1922). The Negro Press in the United States. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-7426-4265-2.

- Dijk, Teun A. van (1995). "Selective Bibliography on Ethnic Minorities, Racism and the Mass Media". Electronic Journal of Communication. ISSN 1183-5656. Archived from the original on 2019-10-05. Retrieved 2017-04-05. (includes US)

- Eldridge, Lawrence Allen. Chronicles of a Two-front War: Civil Rights and Vietnam in the African American Press (University of Missouri Press, 2012)

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2006). "Newspapers". Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195167771.

- Finkle, Lee. Forum for protest: The black press during World War II (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1975)

- Gonzalez, Juan; Joseph Torres (2011). News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media. Verso Books. ISBN 978-1844679423.

- Gershenhorn, Jerry. Louis Austin and the Carolina Times: A Life in the Long Black Freedom Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

- Guskin, Emily, Paul Moore, and Amy Mitchell. "African American media: Evolving in the new era." in The State of the News Media 2011 (2011).

- Henritze, Barbara K. Bibliographic Checklist of African American Newspapers (Genealogical Publishing Com, 1995)

- Hogan, Lawrence D. A black national news service: the Associated Negro Press and Claude Barnett, 1919–1945 (Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1984)[ISBN missing]

- Jones, Allen W. (1979). "The Black Press in the "New South": Jesse C. Duke's Struggle for Justice and Equality". The Journal of Negro History. 64 (3): 215–228. doi:10.2307/2717034. JSTOR 2717034.

- La Brie, Henry G. A survey of Black newspapers in America (Mercer House Press, 1973).[ISBN missing]

- Meier, August (1953). "Booker T. Washington and the Negro Press: With Special Reference to the Colored American Magazine". The Journal of Negro History. 38 (1): 67–90. doi:10.2307/2715814. JSTOR 2715814.

- Morris, James McGrath. Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press (New York: Amistad, 2015). xii, 466 pp.[ISBN missing]

- Oak, Vishnu Vitthal. The Negro Newspaper (Greenwood, 1970)

- Odum-Hinmon, Maria E. "The Cautious Crusader: How the Atlanta Daily World Covered the Struggle for African American Rights from 1945 to 1985." (PhD Dissertation University of Maryland, 2005). [1] Archived 2023-12-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Penn, Irvine Garland (1891). The Afro-American Press and Its Editors. Massachusetts: Willey and Co.

- Pride, Armistead Scott; Clint C. Wilson (1997). History of the Black Press. Howard University Press. ISBN 978-0882581927.

- Prides, Armistead S. A Register and History of Negro Newspapers in the United States: 1827–1950. (1950)

- Simmons, Charles A. The African American press: a history of news coverage during national crises, with special reference to four black newspapers, 1827–1965 (McFarland, 2006).

- Stevens, John D. "Conflict-cooperation content in 14 Black newspapers." Journalism Quarterly 47#3 (1970): 566–568.

- Strickland, Arvarh E., and Robert E. Weems, eds. The African American Experience: An Historiographical and Bibliographical Guide (Greenwood, 2001), pp. 216–230, with long bibliography

- Suggs, Henry Lewis, ed. The Black press in the south, 1865–1979 (Praeger, 1983).

- Suggs, Henry Lewis, ed. The Black Press in the Middle West, 1865–1985 (Greenwood Press, 1996). 416 pp.

- Wade-Gayles, Gloria (1981). "Black Women Journalists in the South, 1880-1905: An Approach to the Study of Black Women's History". Callaloo (11/13): 138–152. doi:10.2307/3043847. JSTOR 3043847.

- Washburn, Patrick S. The African American Newspaper: Voice of Freedom (Northwestern University Press, 2006); covers 1827–1900; emphasis on Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender

- Washburn, Patrick Scott. A question of sedition: The federal government's investigation of the black press during World War II (Oxford University Press, 1986).

- Wolseley, Roland Edgar. The black press, USA (Wiley-Blackwell, 1990).

Primary sources

[edit]- Dunnigan, Alice. Alone Atop the Hill: The Autobiography of Alice Dunnigan, Pioneer of the National Black Press (University of Georgia Press, 2015)

- La Brie, Henry G. III, Black Pulitzers and Hearsts, oral history collection at Columbia University's Butler Library with over 80 interviews with Black publishers and editors