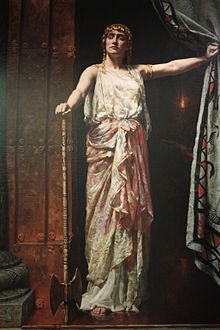

Clytemnestra after the murder of Agamemnon (John Collier, 1882) | |

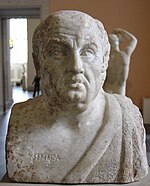

| Author | Lucius Annaeus Seneca |

|---|---|

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Set in | Agamemnon's palace |

Publication date | 1st century |

| Publication place | Rome |

| Text | Agamemnon at Wikisource |

Agamemnon is a fabula crepidata (Roman tragedy with Greek subject) of c. 1012 lines of verse written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca in the first century AD, which tells the story of Agamemnon, who was killed by his wife Clytemnestra in his palace after his return from Troy.

Characters

[edit]- Thyestis umbra (Thyestes' ghost), uncle of Agamemnon

- chorus

- Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon

- nutrix (nurse)

- Aegisthus, son of Thyestes, lover of Clytemnestra

- Eurybates, messenger of Agamemnon.

- Cassandra, Trojan princess, captive of Agamemnon

- Agamemnon, king of Myceneae, and leader of the Greeks in the Trojan War.

- Electra, daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra

- Strophius, king of Phocis, husband of Agamemnon's sister

- Orestes (silent role), son of Agamemnon, brother of Electra

- Pylades (silent role), son of Strophius, friend of Orestes

The scene is laid partly inside and partly outside the palace of Agamemnon at Argos or Mycenae, on the day of the return of the king from his long absence at Troy, beginning in the period of darkness just preceding the dawn.[1]

Plot

[edit]The blood-feud between Atreus and Thyestes was not ended with the vengeance which Atreus wreaked upon his brother. It was fated that Thyestes should live to father upon his own daughter a son, Aegisthus, who would slay Atreus and bring ruin and death upon Agamemnon.[1]

The Trojan War is done, and now the near approach of the victorious king Agamemnon, bringing his captives and treasure home to Argos, has been announced. But his wife Clytemnestra, enraged at Agamemnon because he had sacrificed her daughter Iphigenia at Aulis to appease the winds, and full of jealousy because he brings Cassandra as her rival home, estranged also by the long-continued absence of her husband, but most estranged by her own guilty affair with Aegisthus, is now plotting to slay her husband on his return, gaining both revenge and safety from his anger.[1]

Act I

[edit]The ghost of Thyestes, arriving from the underworld, calls upon his son Aegisthus to carry out the revenge which had been promised him by the oracle.

The Chorus of the Women of Argos or Mycenae complains of exalted fortune as unstable, full of anxieties and cares, and therefore gives preference to a modest life.[2]

Act II

[edit]Clytemnestra, conscious of her own wickedness, and fearing punishment for her adultery now that her husband has just returned, meditates the destruction of Agamemnon as a remedy. The Nurse however, dissuades her from adopting such a step.

Aegisthus comes on the scene and finds Clytemnestra in a hesitating mood and prepared to yield to the wise counsels of the Nurse. He succeeds in diverting Clytemnestra from her new-born resolution, and on again towards her rash purpose.

The chorus of the women of Mycenae and Argos sing a triumphal hymn in honor of Apollo on account of the victory gained at Troy, but introduce laudatory addresses to Juno, Minerva and Jupiter.[2]

Act III

[edit]Eurybates reports that Agamemnon has returned and is now approaching—that a tempest was visited upon them by Pallas, which was made worse for them, through the treachery of Nauplius. Sacrifices are prepared for the gods, and a feast is got ready for Agamemnon. The captives are brought forward.

The Chorus of Trojans bewail the fates and the misfortunes of Troy. Cassandra is seized with one of her prophesying fits, and foretells what dangers are threatening Agamemnon.[2]

Act IV

[edit]Cassandra, when Agamemnon returns, predicts his fate, but she is not believed.

The Chorus of Argos Women sing the praises of Hercules, especially as he was brought up at Argos, and they maintain that his arrows were required by the Fates, for the second downfall of Troy.[2]

Act V

[edit]Cassandra, although she (actually) sees nothing, and is only in the proscenium, foretells what is to happen, and she narrates everything that is progressing in the banqueting hall to those outside concerning the slaughter of Agamemnon.

Electra persuades her brother Orestes to take flight and luckily encounters Strophius. She hands Orestes over to Strophius to be carried away. Electra flies to the altar for protection.

Clytemnestra orders Electra to be dragged away from the altar and thrown into prison. Clytemnestra orders death for Cassandra.[2]

Sources

[edit]There is no earlier known play which serves as an obvious model for Seneca's Agamemnon.[3] The play tells the roughly same story as the Agamemnon by Aeschylus.[3] However the characterisation, structure, and themes of Seneca's play are very different from Aeschylus's play.[3] Agamemnon has only a relatively minor role in Seneca's play, compared with Clytemnestra and Cassandra who have large parts.[4] Other (lost) plays which might have influenced Seneca include Agamemnon by Ion of Chios, Aegisthus by Livius Andronicus, and Clytemnestra by Accius.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Miller, Frank Justus (1917). Seneca. Tragedies. Loeb Classical Library: Harvard University Press.

- ^ a b c d e Bradshaw, Watson (1903). The ten tragedies of Seneca. S. Sonnenschein & Co.

- ^ a b c Tarrant, R. J. (2004). Seneca: Agamemnon. Cambridge University Press. p. 10.

- ^ a b Braund, Susanna (2017). "Agamemnon: Introduction". In Bartsch, Shadi (ed.). Seneca: The Complete Tragedies. Vol. 2. University of Chicago Press. p. 233.

Further reading

[edit]- Otto Zwierlein (ed.), Seneca Tragoedia (Oxford: Clarendon Press: Oxford Classical Texts: 1986)

- John G. Fitch Tragedies, Volume II: Oedipus. Agamemnon. Thyestes. Hercules on Oeta. Octavia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: Loeb Classical Library: 2004)