| Successor | American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1893 |

| Founded at | Oberlin, Ohio |

| Type | Nonprofit |

| Legal status | Defunct |

| Purpose | Activism |

| Leader | Wayne Wheeler |

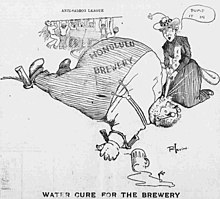

The Anti-Saloon League, now known as the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems, is an organization of the temperance movement in the United States.[1]

Founded in 1893 in Oberlin, Ohio, it was a key component of the Progressive Era, and was strongest in the South and rural North, drawing support from Protestant ministers and their congregations, especially Methodists, Baptists, Disciples and Congregationalists.[2] It concentrated on legislation, and cared about how legislators had voted, not whether they drank or not. Established initially as an Ohio state society, its influence spread rapidly. In 1895, it became a national organization and quickly rose to become the most powerful prohibition lobby in America, overshadowing the older Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Prohibition Party. Its triumph was nationwide prohibition locked into the Constitution with passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919. It was decisively defeated when Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

However, the organization continued – albeit with multiple name changes – and as of 2016, is known as the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems. It remains active in lobbying to restrict alcohol advertising and promoting temperance.[3] Its periodical is titled The American Issue. Member organizations of the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems include "state temperance organizations, national Christian denominations and other fraternal organizations that support ACAAP's philosophy of abstinence".[4]

Organizational structure and operation

[edit]

The League was the first modern pressure group in the United States organized around one issue. Unlike earlier popular movements, it utilized bureaucratic methods learned from business to build a strong organization.[5] The League's founder and first leader,[6] Howard Hyde Russell (1855–1946), believed that the best leadership was selected, not elected. Russell built from the bottom up, shaping local leagues and raising the most promising young men to leadership at the local and state levels. This organizational strategy reinvigorated the temperance movement.[7] Publicity for the League was handled by Edward Young Clarke and Mary Elizabeth Tyler of the Southern Publicity Association.[8]

In 1909, the League moved its national headquarters from Washington to Westerville, Ohio, which had a reputation for supporting temperance. The American Issue Publishing House, the publishing arm of the League, was also in Westerville. Ernest Cherrington headed the company. It printed so many leaflets – over 40 tons of mail per month – that Westerville was the smallest town to have a first class post office.

From 1948 until 1950 the group was named the Temperance League, from 1950 to 1964 the National Temperance League, and from 1964 to 2015 the American Council on Alcohol Problems (ACAP);[7] in 2016 the group rebranded as the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems (ACAAP).[9] As of 2020[update] the organization continues its "neo-prohibitionist agenda",[10] with the addition of "other drugs" such as opioids.[11] ACAAP is headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama.[11]

A museum about the Anti-Saloon League is at the Westerville Public Library.[12]

Pressure politics

[edit]The League's most prominent leader was Wayne Wheeler, although both Ernest Cherrington and William E. "Pussyfoot" Johnson were also highly influential and powerful. The League used pressure politics in legislative politics, which it is credited with developing.[13]

Howard Ball has written that the Ku Klux Klan and the Anti-Saloon league were both immensely powerful pressure groups in Birmingham, Alabama during the Post-World War I period. A local newspaper editor at the time wrote that "In Alabama, it is hard to tell where the Anti-Saloon League ends and the Klan begins".[14] During the May 1928 primary in Alabama, the League joined with Klansmen and members of the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). When an Alabama state senator proposed an anti-masking statute "to emasculate the order's ability to terrorize people", lobbying led by J. Bib Mills, the superintendent of the Alabama Anti-Saloon League, ensured that the bill failed.[15]

When it came to fighting “wet” candidates, especially candidates such as Al Smith in the presidential election of 1928, the League was less effective because its audience was already Republican.[citation needed]

National constitutional amendment

[edit]The League used a multitiered approach in its attempts to secure a dry (prohibition) nation through national legislation and congressional hearings, the Scientific Temperance Federation, and its American Issue Publishing Company. The League also used emotion based on patriotism, efficiency and anti-German sentiment in World War I. The activists saw themselves as preachers fulfilling their religious duty of eliminating liquor in America.[16] As it tried to mobilize public opinion in favor of a dry, saloonless nation, the League invented many of the modern techniques of public relations.[17]

Local work

[edit]The League lobbied at all levels of government for legislation to prohibit the manufacture or import of spirits, beer and wine. Ministers had launched several efforts to close Arizona saloons after the 1906 creation of League chapters in Yuma, Tucson, and Phoenix. A League organizer from New York arrived in 1909, but the Phoenix chapter was stymied by local-option elections, whereby local areas could decide whether to allow saloons. League members pressured local police to take licenses from establishments that violated closing hours or served women and minors, and they provided witnesses to testify about these violations. One witness was Frank Shindelbower, a juvenile from a poor family, who testified that several saloons had sold him liquor; as a result those saloons lost their licenses. However, owners discovered that Shindelbower had perjured himself, and he was imprisoned. After the Arizona Gazette and other newspapers pictured Shindelbower as the innocent tool of the Anti-Saloon League, he was pardoned.[18]

State operations

[edit]At the state level, the League had mixed results, usually doing best in rural and Southern states. It made little headway in larger cities, or among liturgical church members such as Catholics, Jews, Episcopalians and German Lutherans. Pegram (1990) explains its success in Illinois under William Hamilton Anderson. From 1900 and 1905, the League worked to obtain a local option referendum law and became an official church federation. Local Option was passed in 1907 and, by 1910, 40 of Illinois's 102 counties and 1,059 of the state's townships and precincts had become dry, including some Protestant areas around Chicago. Despite these successes, after the Prohibition amendment was ratified in 1919, social problems ignored by the League – such as organized crime – undermined the public influence of the single-issue pressure group, and it faded in importance.[19] Pegram (1997) uses the League's failure in Maryland to explore the relationship between Southern Progressivism and national progressivism. William H. Anderson was the League's Maryland leader from 1907 to 1914, but he was unable to adapt to local conditions, such as the large German element. The League failed to ally with local political bosses and attacked the Democratic Party. In Maryland, as in the rest of the South, Pegram concludes, traditional religious, political, and racial concerns constrained reform movements even as they converted Southerners to the new national politics of federal intervention and interest-group competition.[20]

William M. Forgrave was superintendent of the Massachusetts Anti-Saloon League from 1923 to 1928. In his first year as leader, the statewide referendum on the state's liquor enforcement code was passed by a majority of 8,000 votes. The same referendum had been defeated by 103,000 votes two years earlier.[21] In 1928, the Massachusetts House of Representatives voted 97 to 93 to censure him and strip him of his right to act as a legislative agent after he made unsubstantiated allegations the Massachusetts General Court held a "wild party" and gave away liquor confiscated by the Massachusetts Department of Public Safety.[22][23] The Senate rejected the amendment because Forgrave had censured without a hearing.[24] He resigned as superintendent on November 27, 1928, due to his impending divorce.[21][25]

Post-1928

[edit]Unable to cope with the failures of prohibition after 1928, especially bootlegging and organized crime as well as reduced government revenue, the League failed to counter the repeal forces. Led by prominent Democrats, Franklin D. Roosevelt handily won the U.S. presidency election in 1932 on a wet platform. A new Constitutional amendment passed in 1933 to repeal the 18th Amendment, and the League lost much of its former influence afterwards.

As of 2016, the organization is now known as the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems and remains active in lobbying to restrict alcohol advertising and promoting temperance.[3] It additionally aims to reduce alcohol consumption by Americans.[1] Member organizations of the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems include "state temperance organizations, national Christian denominations and other fraternal organizations that support ACAAP's philosophy of abstinence".[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Martin, Scott C. (December 16, 2014). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. SAGE Publications. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-4833-3108-9.

The American Council on Alcohol Problems (ACAP) is a national organization with branches in 37 of the 50 states. In contemporary terms, ACAP focuses on reducing the number of alcohol advertisements available within the United States, decreasing the availability of alcohol and alcohol-related products, and encouraging Americans to reduce alcohol consumption.

- ^ Rumbarger, John (1989). Profits Power, and Prohibition: Alcohol Reform and the Industrializing of America, 1800–1930. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-88706-782-4.

- ^ a b Ade, George (November 4, 2016). The Old-Time Saloon: Not Wet - Not Dry, Just History. University of Chicago Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-226-41230-6.

- ^ a b Mart, Sarah; Giesbrecht, Norman (2015). "Pinkwashed Drinks: Problems & Dangers". The American Issue. 24 (15).

- ^ Odegard, Peter H. (1928). Pressure Politics: Story of the Anti-Saloon League. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Cherrington, Ernest Hurst (1913). History of the Anti-Saloon League. Westerville, Ohio: The American Issue Publishing Company.

- ^ a b Kerr, K. Austin (1985). Organized for Prohibition: A New History of the Anti-Saloon League. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300032932.

- ^ Martinez, J. Michael (2016). A Long Dark Night: Race in America from Jim Crow to World War II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-5996-6.

- ^ "Home". American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems. The American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016.

- ^ Hanson, David J. (September 12, 2019). "American Council on Alcohol Problems (A Temperance Group Today)". Alcohol Problems and Solutions. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ a b "Philosophy and Programs". American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems. The American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Anti-Saloon League Museum". Westerville Public Library. 2020. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Kerr, K. Austin (1980). "Organizing for Reform: The Anti-Saloon League and Innovation in Politics". American Quarterly. 32 (1): 37–53. doi:10.2307/2712495. ISSN 0003-0678. JSTOR 2712495.

- ^ Ball, Howard (1996). Hugo L. Black: Cold Steel Warrior. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536018-9.

- ^ Feldman, Glenn (1999). Politics, Society, and the Klan in Alabama, 1915–1949. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0984-8.

- ^ Lamme, Margot Opdycke (2004). "Tapping into War: Leveraging World War I in the Drive for a Dry Nation". American Journalism. 21 (4): 63–91. doi:10.1080/08821127.2004.10677610. ISSN 0882-1127. S2CID 153796704.

- ^ Lamme, Margot Opdycke (2003). "The 'Public Sentiment Building Society': the Anti-saloon League of America, 1895–1910". Journalism History. 29 (3): 123–32. doi:10.1080/00947679.2003.12062629. ISSN 0094-7679. S2CID 197720589.

- ^ Ware, H. David (1998). "The Anti-Saloon League Wages War in Phoenix, 1910: the Unlikely Case of Frank Shindelbower". Journal of Arizona History. 39 (2): 141–54. ISSN 0021-9053.

- ^ Pegram, Thomas R. (Autumn 1990). "The Dry Machine: the Formation of the Anti-Saloon League of Illinois". Illinois Historical Journal. 83 (3): 173–86. ISSN 0748-8149.

- ^ Pegram, Thomas R. (1997). "Temperance Politics and Regional Political Culture: the Anti-saloon League in Maryland and the South, 1907–1915". Journal of Southern History. 63 (1): 57–90. doi:10.2307/2211943. JSTOR 2211943.

- ^ a b "Forgrave Out As State Anti-Saloon League Head". The Boston Daily Globe. November 28, 1928.

- ^ "House Censures Supt Forgrave". The Boston Daily Globe. July 13, 1928.

- ^ "Censures Bay State Dry Leader". The New York Times. July 13, 1928.

- ^ "Senate Refuses Forgrave Censure". The Boston Daily Globe. July 18, 1928.

- ^ "Wife Of Forgrave Asks Reno Divorce". The Boston Daily Globe. October 19, 1933.

Further reading

[edit]- Ade, George. The Old-Time Saloon: Not Wet – Not Dry, Just History (1931; reprint 2020) excerpt

- Andersen, Lisa M. F. The Politics of Prohibition: American Governance and the Prohibition Party, 1869–1933 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- The Anti-Saloon League of America. Cherrington, Ernst Hurst (ed.). The Anti-Saloon League Year Book: 1908–1931. Westerville, Ohio: The American Issue Publishing Company – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- Clark, Norman H. (1976). Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition. Norton. – a favorable history

- Donovan, Brian L. (April 1995). "Framing and Strategy: Explaining Differential Longevity in the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League". Sociological Inquiry. 65 (2): 143–55. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.1995.tb00410.x. ISSN 0038-0245.

- Ewin, James Lithgow (1913). The Birth of the Anti-Saloon League. Washington, D.C.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hamm, Richard F. (1995). Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment: Temperance Reform, Legal Culture, and the Polity, 1880–1920. Studies in Legal History. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807821817.

- Lerner, Michael A. (2007). Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674024328. online review

- McGirr, Lisa. The war on alcohol: prohibition and the rise of the American state (2016) online review

- Sponholtz, Lloyd (1976). "The Politics of Temperance in Ohio, 1880–1912". Ohio History. 85 (1): 4–27. ISSN 0030-0934.

- Szymanski, Ann-Marie E. (2003). Pathways to Prohibition: Radicals, Moderates, and Social Movement Outcomes. Duke University Press Books. ISBN 978-0822331810.

External links

[edit]- American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems

- Ohio History Central (Westerville)

- American Council on Alcohol Problems Records

- Anti-Saloon League & Prohibition History

- Anti-Saloon League Origins

- Anti-Saloon League Leaders

- Anti-Saloon League of Nebraska records[usurped] at Nebraska State Historical Society

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Anti-Saloon League