| Apodaca prison riot | |

|---|---|

| Part of Mexican Drug War | |

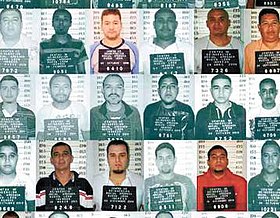

Mug shots of the Zeta fugitives. | |

| Location | Apodaca, Nuevo León, Mexico |

| Coordinates | 25°52′01″N 100°15′21″W / 25.86694°N 100.25583°W |

| Date | 19 February 2012 2:00 am – 6:00 am |

| Target | Gulf Cartel |

Attack type | Mass murder, prison riot, prison escape |

| Weapons | Clubs, knives, and rocks[1] |

| Deaths | 44 (All Gulf Cartel members)[2] |

| Injured | 12 (During main riot)[3] 22 (After later riots)[4] |

| Perpetrator | Los Zetas |

No. of participants | 10–12 (Zeta killers)[5][6] 21 (Prison officers)[7] |

The Apodaca prison riot occurred on 19 February 2012 at a prison in Apodaca, Nuevo León, Mexico.[3] Mexico City officials stated that at least 44 people were killed, with another twelve injured.[3] The Blog del Narco, a blog that documents events and people of the Mexican Drug War anonymously, reported that the actual (unofficial) death toll may be more than 70 people.[8] The fight was between Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel, two drug cartels that operate in northeastern Mexico.[9] The governor of Nuevo León, Rodrigo Medina, mentioned on 20 February 2012 that 30 inmates escaped from the prison during the riot.[10] Four days later, however, the new figures of the fugitives went down to 29.[11] On 16 March 2012, the Attorney General's Office of Nuevo León confirmed that 37 prisoners had actually escaped on the day of the massacre.[12] One of the fugitives, Óscar Manuel Bernal alias La Araña (The Spider), is considered by the Mexican authorities to be "extremely dangerous," and is believed to be the leader of Los Zetas in the municipality of Monterrey.[13] Some other fugitives were also leaders in the organization.[14]

The fight broke out around 2:00 am local time between inmates in one high security cell block and inmates of another security cell block.[15][16] The guards of the prison allowed the Zeta members to surge from Cellblock C into Cellblock D and attack the Gulf Cartel members, who were sleeping.[17] A guard was taken hostage during the melee, and mattresses were set on fire.[18] Security personnel regained control of the prison by 6:00 am.[3] Each cell block contained roughly 750 inmates, with members of rival drug cartels normally separated.[15] Not all the prisoners were able to be counted, but by the time the dead prisoners were counted, the public security spokesperson speculated that the riot may have been started as a cover for a jail break.[15] It was later confirmed that the riot and brawl "served as cover for a massive jailbreak" for the members of the Zetas drug cartel, who attacked the Gulf Cartel inmates.[19]

According to The Wall Street Journal and El Universal, the mass murder in Apodaca is the deadliest prison massacre in Mexico's history.[20][21] Milenio news, in addition, mentioned that the prisons in the state of Nuevo León are plagued with violence, and that they are "under the control of the criminal groups" that operate in the area.[22] The Apodaca prison was built to house 1,500 inmates, but had around 3,000 incarcerated at the time of the riot.[16] After the split of the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas in early 2010, both groups have been battling for Monterrey and other areas in northeastern Mexico.[23] And although no firearms were used in the fight between the two groups, the fact that their turf war goes as far as to Mexico's prison system only "emphasizes the bitterness of their rivalry."[24] More importantly, however, the massacre, and the involvement of the prison guards in the escape, highlights the problems facing Mexico's—and the rest of Latin America's prison system.[24]

Cause

[edit]The prison riot is believed to have started when members of the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas clashed in the prison, using sharp-edged knives, stones, burning devices, and possibly firearms to kill rival cartel members.[25] A prison spokesperson denied that firearms were involved.[15] Some of the dead were strangled, thrown out of windows, stabbed, beheaded, hanged, bludgeoned, and crushed.[16][26] An investigation was immediately launched into whether some of the 17 prison guards on duty colluded in the fight by unlocking the doors between the two wings of the prison.[16] The prison director, the director of security, and the supervisor on duty were all detained for questioning.[15] By the time the riot ended, 44 inmates who were reportedly members of the Gulf Cartel had been killed.[27] Moreover, 30 inmates of the Los Zetas drug cartel were allowed to escape by the prison guards, and government sources reveal that the fugitives were high-ranking members in the organization, former police officers, or drug dealers.[28]

Since President Felipe Calderón launched a military-led offensive against the cartels in Mexico in 2006, Mexican prisons have turned into battlefields for rival cartels, often leading to violent fights and frequent deaths.[20] Many prisons are essentially run by one cartel or another.[20] Eric Olson of the Mexico Institute at Wilson Center remarked, "The strategy has been to arrest a lot of people, but when you warehouse prisoners in prisons that are overcrowded and poorly managed, you are likely to have this kind of warfare breakout inside prisons."[20] The Apodaca prison riot was the third riot to result in 20 or more deaths since October 2011.[20] And according to the writers of InSight Crime, Mexico's prison system is slipping into anarchy, with inmates slaughtering each other at alarming rates;[29] below is a quote from a newspaper, which sums up Mexico's penitentiary system and its problems: "Gang violence and break-outs are common in Mexico's notoriously overcrowded and corrupt prison system."[30]

Investigation

[edit]

Fifteen days before the massacre, the family members of the fugitives claimed that the inmates had planned out the prison break.[31] And as the investigations began, officials in northern Mexico reported that Los Zetas, with the help of several jail guards, helped the 30 fugitives escape from the prison.[32] Four days after the incident, however, the figures went down to 29, because they had "recounted" one of the fugitives.[11] Other sources mention that one of the 30 fugitives was actually killed in the massacre.[33] The governor speculated that the jailbreak "was planned."[34] And Jorge Domene, the security spokesman for the state of Nuevo León, does not discard the possibility that Óscar Manuel Bernal Soriano alias La Araña may have been the major leader in the riot and escape in the prison.[35] The Attorney General of Mexico and the National Human Rights Commission are leading the investigations.[36][37] Investigations indicate that the directors of the prison accepted between $40,000 and $15,000 pesos, and the guards around $6,000 pesos, in bribes each month.[38] By 16 March 2012, it was confirmed that Óscar Manuel Bernal, alias La Araña, was allowed to hold "parties with musical groups and women."[38]

El Universal mentioned on 24 February 2012 that the family members of the prisoners claimed that the inmates had certain "privileges" inside the jail, like holding big parties, sexual orgies with prostitutes, and "special permissions" from the authorities of prison in Apodaca.[39] The mother of one of the prisoners said that his son had claimed that the prison was "under the control of the narcos (drug traffickers)," and that they were often given permission "to leave the prison and come back after they had finished doing their business."[39] Another witness claimed that the guards were also directly involved in the weekly escape of the prisoners and the "drug trafficking business" inside the prison walls.[39] The prison, they said, was under the "law of Los Zetas," and it only cost the prisoners up to $40,000 Mexican pesos (about $3120 U.S. dollars) to operate freely inside the prison.[39] In addition, it cost the Zetas more than $2.5 million pesos a year to bribe the officials in the prison.[40]

CNNMéxico published an article exposing the number of prison fights in Mexico since the start of the Mexican Drug War in late 2006, as well as the figures behind each prison (population and capacity), and the number of federal prisons in the country.[41]

Fraudulent numbers

[edit]On 16 March 2012, the Attorney General's Office Nuevo León corrected the figures of the inmates who managed to escape the prison during the massacre, confirming that the actual prisoners who escaped were 37—not 29—as previously stated.[42] One of the fugitives was captured on 6 March 2012, however, so 36 prisoners were at large when this announcement was given.[43] The state government attributed the "irregularities" of the previous reports to the manager of the prison, Jerónimo Miguel Andrés Martínez, who presented "fraudulent documents and misleading reports" the day of the massacre.[42] In addition, two prisoners who were pronounced as fugitives on 19 February 2012 never escaped from the prison.[44] The Attorney General's Office Nuevo León asserted that the new figures are definitive.[45]

The Mexican authorities offer up to 12.4 million pesos for information leading to the arrests of the fugitives.[46]

Aftermath

[edit]The governor of Nuevo León mentioned that 30 inmates, reportedly from the criminal group Los Zetas, escaped from the prison with the "complicity of the prison authorities," and that 18 prison guards were being investigated on 20 February 2012.[47] Nine of them confessed to have helped the prisoners escape,[48] but 19 have been found guilty as of 21 February 2012.[49] An investigation continues as to why the prison cells were opened, allowing the riot between the rival drug gangs.[50] Mexican prisons have been notorious for being overpopulated, lacking adequate supervisors, and failing to meet prisoners' needs or prevent them from reoffending after release.[51] Of the 44 killed, 35 have been identified.[52] Rodrigo Medina is offering more than 10 million Mexican pesos (almost $800,000 U.S. dollars) for information leading to the arrest of the fugitives that escaped in the mass jailbreak.[53]

During the prison riot, over 300 family members arrived at the scene.[54] The families then demanded the authorities to hand in the bodies of their loved ones.[55] Other family members, nonetheless, confronted the police forces after failing to obtain information of what had occurred.[56] The National Human Rights Commission reported that 25 minors were in the prison during the deadly riot.[57] The mayor of García, Nuevo León, Jaime Rodríguez, worries that the escape of Oscar Manuel Bernal Soriano alias La Araña (The Spider), a high-ranking Los Zetas leader, might bring reprisals from him and the cartel.[58]

On 21 February 2012 the United Nations asked for the Mexican authorities to work "exhaustively and independently" to find those responsible for the massacre.[59] In addition, they condemned the massacre and asked for the National Human Rights Commission to "monitor conditions of detention throughout Mexico."[60] Moreover, Egidio Torre Cantú, the governor of the neighboring state of Tamaulipas, has agreed to search for the fugitives of the prison break in his state, too.[61] As a result of the "crisis" in the prison systems of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León, the president of Mexico, Felipe Calderón, promised to begin a project to create 8 to 10 prisons by the end of his term, and reiterated that this project forms part of his "security strategy" to prevent Mexico from falling in the hands of the organized crime groups.[62][63] That effort, he mentioned, has "never been done in the past 20 years in Mexico."[64] Alejandro Poiré Romero, moreover, mentioned that there will be no more federal inmates in state prisons by the end of 2012, and recognized that that was one of the many "weaknesses" of the Mexican prison systems.[65] On 24 February 2012 Jaime Castañeda Bravo, the Secretary of Public Security in Nuevo León was removed from office by the state government.[66] Concrete walls were later installed around the prison in Apodaca to "elevate the security measures" of the area.[67] In addition, the police forces of the city of Apodaca recruited former Mexican military officers to form part of their body.[68] The state government of Nuevo León asked the Federal government of Mexico to take control of the prison in Apodaca on 24 February 2012, the same day 10 prisoners were found guilty of the massacre.[69]

Although the events are not related, in the prison of Topo Chico, just north of Monterrey, 3 inmates were killed two days after the massacre in Apodaca.[70]

Protests and later riots

[edit]On 21 February 2012 the families of the inmates and the deceased prisoners protested and confronted the police forces outside the prison in Apodaca. In the heat of the moment, the families burned objects and threw rocks at the authorities.[71] Inside the prison, riots continued after several inmates were being transported from the prison in Nuevo León to other prisons out-of-state.[72] The Mexican military and the Fuerza Civil police forces guarded the area.[73]

Anonymous' operation

[edit]During the disturbances outside the prison, the hacker group Anonymous blocked the official page of the municipality of Apodaca as a "protest for the massacre."[74]

Prisoners transfer

[edit]After the massacre and disturbances in the prison in Apodaca, three high-ranking leaders of Los Zetas were transferred on 22 February 2012 to Puente Grande, a maximum security prison in Jalisco.[75] There were 22 inmates injured after the prisoners' transfer triggered another riot.[76] One of the prisoners that was transferred, known as El Comandante Chabelo, was reportedly the leader of Los Zetas in certain parts of Nuevo León and Coahuila, and is believed to be responsible for drug trafficking, aggression to military officers and federal agents, as well as conducting other organized crime activities.[77] The two other transfers, known by their aliases of El Junior and El Extraño, were contract killers of Los Zetas.[78] La Vanguardia, however, noted that the prison in Jalisco has "worse conditions than in Apodaca," and as of February 2012, the overpopulation of that prison ranges from 130 to 150%.[79]

The transfer of the prisoners caused a series of protests inside and outside the prison in Apodaca, and smog could be seen from the outside of the prison walls.[80]

'Narco-blockades' in Monterrey

[edit]The capital city of Monterrey was not immune to the effects of the prison break and massacre, and on 24 February 2012 it experienced a series of the narco-blockades, a military technique used by the drug cartels to cut off the roads and slow down authorities who were pursuing them.[81] Law enforcement officials say that cartels block roads "as a show of force."[82] According to reports by CNNMéxico, alleged members of a drug cartel used buses and stripped people from their cars to block important avenues in Monterrey.[83] Then, they began to put up several narco-banners against the state government of Nuevo León and the current governor, Rodrigo Medina.[83] Two blockades were reported that day.[84]

'Narco-banners' in Monterrey

[edit]The Blog del Narco published an article on 25 February 2012 reporting that the criminal group Los Zetas had put up several narco-banners, messages hung from bridges or in other public places,[85] around the city of Monterrey at around 8:00 pm[86] According to a state police investigator who spoke on condition of anonymity, gunmen carjacked several cars and buses and blocked busy avenues in Monterrey to put up the messages allegedly signed by Heriberto Lazcano alias Z-3 and Miguel Treviño Morales alias Z-40, the two supreme leaders of the entire Los Zetas.[87] The banners read the following:

Nuevo León is Zeta territory, and we demonstrate our power with facts, even if Rodrigo Medina doesn't like it, he will have to obey because we supported him to become a governor...That's why I do whatever I want in Nuevo León because it belongs to me. I release whomever I want from prison and kill the same way I killed the enemy, Gulf Cartel. Accept it. The only thing that the government of Calderón and the next president can do is come to an agreement with us, because if they don't, we will overthrow the government and we will take the power by force the same way we have been doing it till now…Here, Los Zetas, are the ones with power.

The banners also mentioned that Rodrigo Medina, the governor, accepted briberies from the criminal organizations.[89] The governor, however, reacted by saying that the messages posted by the cartel should be "discredited by the entire population," since they only "damage the public institutions" of the country.[90] In addition, Medina reiterated his efforts to adopt efficient security measures for the state.[90] Álvaro Ibarra, the Secretary General of Nuevo León, said that the banners "divide the citizens of Nuevo León," and invited the media and the citizens to recognize that the banners only serve that purpose.[91] Moreover, he mentioned that the message is a clear sign of "desperation" by the cartel due to the major blows it has received by the Mexican government.[91] Aldo Fasci Zuazua, a member of the Ecologist Green Party of Mexico, said that the banners may not have been written by Los Zetas.[91]

Arrests

[edit]The 21 former functionaries from the prison in Apodaca were apprehended on 15 March 2012.[92] Among them were three high-level functionaries.[92]

As of 3 August 2012, 24 out of the 37 fugitives have been arrested or killed.[93]

Past incidents

[edit]Prison fire

[edit]In the same prison in Apodaca in May 2011, a fire erupted in the prison's psychiatric ward, killing 14 inmates and injuring 35.[94] The causes of the fire have not been proven.[95]

Prison breaks

[edit]In November 2011, in the same prison in Apodaca, 3 inmates were able to escape, but nothing was brought to light until the Mexican military counted the list of prisoners and noticed that three of them were missing.[96]

In Apatzingán, Michoacán on 5 January 2004, dozens of gunmen stormed a prison and released 25 inmates in only fifteen minutes before fleeing the scene.[97] On 25 March 2010 in the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, 40 inmates escaped from a federal prison.[98] Authorities are still trying to understand how the prisoners escaped.[99] The authorities mentioned that the incident is "under investigation," but did not give further information.[100] In the border city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, 85 inmates escaped from a prison on 10 September 2010.[101] Reports first indicated that there were 71 fugitives, but the correct figures were later released.[102] On 5 April 2010, in the same prison, a convoy of 10 trucks filled with gunmen broke into the cells and liberated 13 inmates, and the authorities later mentioned that 11 of them were "extremely dangerous."[103] Also in Reynosa, 17 inmates escaped from a federal prison on 9 October 2008;[104] another 17 escaped after "digging a tunnel" in the prison in Reynosa on 25 May 2011.[105] In Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas on 17 December 2010, about 141 inmates escaped from a federal prison. At first, estimates mentioned that 148 inmates had escaped, but later counts gave the exact figures.[106] The federal government "strongly condemned" the prison breaks and said that the work by the state and municipal authorities of Tamaulipas "lack effective control measures" and urged them to strengthen their institutions.[107] A confrontation inside a maximum security prison in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas on 15 July 2011 left 7 inmates dead and 59 escaped.[108] The 5 guards that were supposed to supervise have not been found, and the Federal government of Mexico urged the state and municipal authorities to strengthen the security of their prisons.[109] Consequently, the federal government did not hesitate to assign the Mexican Army and the Federal Police to vigilate the prisons until further notice; they were also left in charge of searching for the fugitives.[110] CNN mentioned that the state government of Tamaulipas later recognized "their inability to work with the federal government."[111] In the State of Mexico 8 prisoners escaped from a prison after making a hole through the wall on 19 April 2010.[112]

In a prison in the state of Zacatecas, on 16 May 2009, an armed commando liberated 53 Gulf Cartel members using 10 trucks and even a helicopter.[113] 3 inmate escaped from a prison in Tehuantepec, Oaxaca on 13 July 2010.[114] In Morelos, 6 prisoners escaped after killing the prison director on 14 July 2010.[115] 5 federal inmates escaped from a prison in Cancún on 31 December 2010, although authorities reported the incident until 5 January 2011.[116] In Chihuahua, Chihuahua on 11 January 2012, gunmen confronted the prison guards, where 10 inmates were able to escape.[117] In Ahualulco de Mercado, Jalisco, 8 inmates escaped from a prison on 27 April 2011.[118] In Culiacán, Sinaloa on 10 March 2011, 3 high-profile inmates escaped from a prison.[119] On 2 January 2012, the same prison experienced the jailbreak of 4 inmates.[120] In Veracruz, a total of 32 inmates escaped from three prisons on 19 September 2011.[121] On 27 November 2011, in San Pedro Cholula, Puebla, 11 inmates escaped from a federal prison.[122] On 9 December 2006 in the resort city of Cancún, 80 inmates escaped from a prison after a prison riot; 63 of them were captured.[123] On 28 April 2012 in Calera, Zacatecas, 10 inmates escaped from a prison.[124]

According to CNN, more than 400 prison inmates escaped from several prisons in Tamaulipas from January 2010 to March 2011 due to corruption.[125]

Prison killings

[edit]On 15 October 2011, in the border city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, 20 inmates were killed and 12 were severely wounded in a prison brawl.[126] Some sources reveal that the killings were indeed "planned executions."[127] Earlier on 6 August 2010, 14 inmates were also killed in a riot at the federal prison in Matamoros.[128] Moreover, in 1991, the time when Juan García Ábrego was the supreme leader of the Gulf Cartel, the federal prison in Matamoros experienced the massacre of 18 people.[129][130][131] In the nearby border city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, 21 inmates were killed after a shooting inside the prison on 20 October 2008.[132]

On 26 July 2011 in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, a prison brawl left 17 inmates dead and 4 injured after "one group of inmates attacked rivals from another drug gang."[133] Some of the corpses were shot with assault rifles, and authorities investigates whether the weapons used in the attack were "stolen from prison guards, homemade or smuggled" inside the prison.[134] Surveillance videos show how two gangs of the Sinaloa Cartel and the Juárez Cartel stormed the prison with assault rifles.[135] In a prison in Cadereyta Jiménez, Nuevo León, 7 inmates were killed and 12 were injured on 14 October 2011.[136]

On 4 January 2012, in the city of Altamira, Tamaulipas, 31 were killed and 13 were injured in a prison brawl; the brawl was, according to local authorities, between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas, their former allies.[137][138] In the state of Durango, 19 inmates were killed in the prison of Gómez Palacio on 25 August 2009;[139] in the same prison on 21 January 2010, about 23 inmates were killed in a brawl.[140] On 19 May 2011, a shooting inside a prison in Durango left 8 prisoners dead,[141] and on 15 November 2010 a group of gunmen threw a grenade inside the prison.[142] In Tijuana, Baja California on 18 September 2008, a total of 19 inmates were killed in a brawl between rival drug cartel members.[143] In Mazatlán, Sinaloa on 14 June 2010, a group of gunmen entered a prison, killed the guard, and then entered a cell and massacred 29 people.[144]

73 inmates were killed in the prison in Apodaca between the start of the Mexican Drug War in December 2006 to February 2012.[145]

Reactions

[edit] Mexico – President Felipe Calderón promised to create 10 top-notch prisons by the end of his term, in order "to counteract the crisis" in the prisons of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León.[146]

Mexico – President Felipe Calderón promised to create 10 top-notch prisons by the end of his term, in order "to counteract the crisis" in the prisons of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León.[146]

- PRI – The governor of Nuevo León, Rodrigo Medina, member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, claimed that despite the prison break and the masacre, "the State has not lost control of the prisons." Nonetheless, he pointed out that this incident may spark violence all around Nuevo León.[147]

- PAN – The National Action Party asked Congress to "unfreeze" the dead bills and allow the prison reforms by Calderón to be implemented.[148]

- PRD – The Party of the Democratic Revolution said that the next president of Mexico should "establish a new model for social readaptation" to improve the conditions of the country and its prisons.[148]

- PT – The Labor Party asked in Congress for a "detailed investigation" on the conditions of the prison and for the National Human Rights Commission to intervene.[149]

- PVEM – The Ecologist Green Party of Mexico said that the penitentiary system in Mexico has "collapsed," and asked for a complete and "integral reconstruction" of the prisons in the country.[150]

– In the state of Nuevo León, the president of the Citizen Committee for Public Security (CCSP), José Antonio Ortega, called for Rodrigo Medina to step down as governor of the state.[151] In addition, he urged the Mexican government to hold itself responsible for the violence and not blame the United States.[152]

– In the state of Nuevo León, the president of the Citizen Committee for Public Security (CCSP), José Antonio Ortega, called for Rodrigo Medina to step down as governor of the state.[151] In addition, he urged the Mexican government to hold itself responsible for the violence and not blame the United States.[152] – The state of Coahuila emitted a security alert for the possible presence of the fugitives due to the proximity it has to Nuevo León.[153]

– The state of Coahuila emitted a security alert for the possible presence of the fugitives due to the proximity it has to Nuevo León.[153] – The state of Tamaulipas emitted a security alert and offered to work with the state of Nuevo León to find the fugitives.[154]

– The state of Tamaulipas emitted a security alert and offered to work with the state of Nuevo León to find the fugitives.[154] – The authorities of the state of San Luis Potosí are collaborating with Nuevo León to find the fugitives.[155]

– The authorities of the state of San Luis Potosí are collaborating with Nuevo León to find the fugitives.[155]

United Nations – United Nations urged the Mexican government to work exhaustively in the investigation and find those responsible; in addition, they asked the government to meet the "basic standards" in their prison systems.[156]

United Nations – United Nations urged the Mexican government to work exhaustively in the investigation and find those responsible; in addition, they asked the government to meet the "basic standards" in their prison systems.[156]- Amnesty International – The AI organization echoed that Mexico has "failed to implement the urgently needed reforms." They also mentioned that the prison had "persistent and worsening human rights violations" before the massacre.[157]

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- Dozens killed in Mexican prison riot – The Telegraph

- (in Spanish) Crisis carcelaria en Apodaca: masacre, fuga, corrupción – Milenio

- (in Spanish) Galería: Los 30 reos que se fugaron en Nuevo León – Blog del Narco

- (in Spanish) En el caso Apodaca hubo incompetentes, ciegos y sordos – La Vanguardia

- (in Spanish) NL: se fugaron 30 "Zetas" con apoyo externo y de autoridades – El Universal

References

[edit]- ^ "Los 44 reclusos fueron asesinados uno por uno". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ "Cesan a todo el personal del Cereso de Apodaca". Animal Político (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Dozens killed in Mexico prison fight". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Traslado de reos deja 22 heridos en penal de Apodaca". Yahoo! News (in Spanish). 22 February 2012. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Ya hay 10 asesinos identificados: PGJE". Milenio (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Identifican a reos agresores en masacre de Cereso de Apodaca". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Dan formal prisión a directivos y custodios del penal de Apodaca". Proceso (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Motín en Nuevo León: oficial 38 reos muertos, extraoficial al menos 70". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Post, Washington (21 February 2012). "Drug cartel blamed in prison riot that killed 44". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Funcionarios, cómplices en fuga de 30 reos en Apodaca, dice el gobernador". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Son 29 fugados de Apodaca, rectifica PGJNL". El Universal (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Del penal de Apodaca se fugaron 37 reos, no 29, corrigen las autoridades". Animal Politico (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Reo fugado en NL, de alta peligrosidad". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Eran ex jefes de plaza algunos de los fugados". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Mexican prison officials detained after deadly Apodaca riot". Herald Sun. 19 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Dozens of inmates killed in gang fight in Mexican jail". BBC News. 19 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Malkin, Elisabeth (21 February 2012). "Guards Implicated in Mexico Prison's Deadly Gang Attack". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "44 killed in Mexican prison melee". CNN. 19 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson, Tracy (21 February 2012). "Mexico prison riot was cover for jailbreak, officials say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Jose de Cordoba (19 February 2012). "Mexico Prison Riot Leaves 44 Dead". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Mueren 44 reos en riña en penal de NL". El Universal (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Penales de NL, en manos de los grupos delictivos". Milenio (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Mexican jail chiefs sacked after deadly riot". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ a b Fox, Edward (20 February 2012). "Zetas-Gulf Cartel Prison Fight' Leaves 44 Dead". InSight Crime. Retrieved 16 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Confirman 44 muertos en penal de Apodaca". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Monterrey prison riot covers mass escape by gang members". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Reos asesinados eran del cártel del Golfo". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "La "cacería" de reos, para encubrir fuga". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Corcoran, Patrick (24 February 2012). "How to Fix Mexico's Broken Prisons". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ "Mexico sacks Apodaca jail boss over Monterrey riot". BBC News. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Evasión de Apodaca, planeada 15 días antes". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Mexico Prison Riot Staged by Zetas as Cover for Mass Escape, Officials Say". Fox News. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Por error, ponen a reo muerto en Apodaca en la lista de fugados". Proceso (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Mexico Says Drug-Gang Convicts Escaped in Prison Riot". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "No descartan que el zeta "Spider" liderara fuga de reos en Apodaca". Milenio (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "La PGR inicia una investigación por la muerte y fuga de reos en Apodaca". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 23 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "La CNDH inicia una investigación sobre la muerte de 44 reos en Apodaca". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 22 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Cuatro directivos del penal de Apodaca reciben orden de aprehensión". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Reos "entraban y salían como Juan por su casa"". El Universal (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Seguridad costaba a Zetas 2.5 mdp anuales en Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). 15 March 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ "Reos federales colapsan sistemas carcelarios estatales". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 2 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ a b "El gobierno de Nuevo León aumenta el número de fugados de Apodaca". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Rectifican, son 36 los reos fugados en Apodaca". Yahoo News (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Suman 37 los fugados en Apodaca.- NL". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Son 37 y no 29 los reos fugados de Apodaca". Proceso (in Spanish). 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Salazar, Patricia (17 March 2012). "Aumenta cifra de reos fugados de Apodaca; sube recompensa". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "A la caza de 30 reos fugados de penal de Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Nueve custodios confirman su participación en la fuga de Apodaca". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Aumentan a 16 los custodios implicados en motín en Apodaca: Domene". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Mueren 44 reos en riña en penal de Nuevo León". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "El caos de las cárceles". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Identifican a 35 reos muertos en penal de Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). 19 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Zetas gang killed rivals, escaped at Mexico prison". CBS News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Familiares de internos viven horas de angustia". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Familiares reclaman cuerpos de reos". Milenio (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Tragedias en prisiones de México: Apodaca". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 19 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Había 25 menores durante motín en Apodaca: CEDH". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Teme Jaime Rodríguez represalias por fuga de "La Araña"". Milenio (in Spanish). 20 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "La ONU pide pesquisa independiente tras muertes en prisión de Nuevo León". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Palabras de la Portavoz de la Sra. Navi Pillay, Alta Comisionada de la ONU-DH sobre los hechos del pasado domingo en el reclusorio de Apodaca Nuevo León" (PDF). El Universal (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Rastrean en Tamaulipas a los reos fugados". El Universal (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Martínez, Fabiola (21 February 2012). "Al final de este sexenio habrá 8 nuevos centros de reclusión, dice Poiré". La Jornada (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Román, José Antonio (21 February 2012). "En este año, 10 nuevas penitenciarías, promete el presidente Calderón". La Jornada (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Arellano, Silvia (21 February 2012). "Estados generan crisis con sus sistemas penitenciarios: Calderón". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "No habrá reos federales en cárceles estatales al terminar sexenio: Segob". Excélsior (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "El gobierno de Nuevo León destituye al secretario de Seguridad Pública". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Refuerzan con muros de concreto penal de Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). 1 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Policía de Apodaca recluta ex militares". El Universal (in Spanish). 1 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "dentifican a autores de la matanza en el penal de Apodaca". Proceso (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Arroyo, Alejandra (21 February 2012). "Mueren 3 presos durante riña en el penal de Topo Chico, Nuevo León". La Jornada (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Supuestos familiares de reos protestan fuera de la prisión de Apodaca". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Traslado de capo originó nuevo motín en Apodaca". Yahoo! News (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Reportan nuevos disturbios en penal de Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Grupo Anonymus bloquea página web de Apodaca". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Trasladan a tres líderes de Los Zetas del Penal de Apodaca a Puente Grande". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 22 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Deja 22 heridos operativo en penal de Apodaca". Televisa (in Spanish). 22 February 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Trasladan a 3 "zetas" a penal de Puente Grande". El Universal (in Spanish). 23 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Trasladan reos de Apodaca a penal de máxima seguridad". Milenio (in Spanish). 22 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Luna, Adriana (24 February 2012). "Reclusorios de Jalisco presentarían situaciones peores que en Apodaca". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Traslado de capos "calienta" el Cereso". Milenio (in Spanish). 22 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Chapa, Sergio (23 April 2010). "'Narco-Blockade' reported in Reynosa neighborhood". KGBT-TV. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Mexican cartel blockades streets in Monterrey". BBC News. 14 August 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Un grupo de supuestos delincuentes bloquean avenidas de Monterrey". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 24 February 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "La violencia no cesa en Monterrey y los bloqueos regresan a la ciudad". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 25 February 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Ellingwood, Ken (28 October 2009). "Grim glossary of the narco-world". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Narcomantas que aparecieron en Nuevo León son firmadas por Los Zetas, mencionan a Medina y a Calderón". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 25 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Encaran Zetas a gobernador Medina con narcomantas". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 25 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Security Chief Fired after Apodaca Prison Riot – Heriberto Lazcano and Z40 Leave Manta". Borderland Beat. 25 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Acusan en narcomanta a gobernador de Nuevo León de recibir dinero ilícito". Proceso (in Spanish). 25 February 2012. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b "El gobierno de Nuevo León dice que mantas buscan dividir a la sociedad". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 25 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Ordenan aprehensión contra 21 ex funcionarios de Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). 15 March 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ "Presentan a La Cría reo fugado del Penal de Apodaca". Blog del Narco. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "44 killed in Mexican prison melee". CNN. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "Un incendio en un penal de Nuevo León deja 14 internos muertos". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 20 May 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "El director del penal de Apodaca era vinculado a corrupción en cárceles". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 25 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 25 reos de penal de Michoacán". Esmas.com (in Spanish). 5 January 2004. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 40 reos de penal en Matamoros". El Universal (in Spanish). 25 March 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 40 reos de Penal de Matamoros". El Economista (in Spanish). 25 March 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "40 reos se fugan de penal de Matamoros". CNN Mexico (in Spanish). 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "85 reos escaparon del penal de Reynosa, precisa el gobierno". CNN México (in Spanish). 10 September 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Al menos 71 reos se fugan de un penal de Reynosa, en Tamaulipas". CNN México (in Spanish). 10 September 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Un comando libera a trece prisioneros de un penal de Reynosa". CNN Mexico (in Spanish). 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 17 reos de penal de Reynosa ayudados por custodios". El Universal (in Spanish). 9 October 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Chapa, Sergio (25 May 2011). "17 prisoners dig tunnel to freedom at Reynosa prison". Valley Central. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Al menos 148 presos se escapan de una cárcel de Tamaulipas". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 17 December 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Tamaulipas cesa a directivos de penal por la fuga de los 141 reos". CNN México (in Spanish). 17 December 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Al menos siete muertos y 59 reos fugados en una cárcel de Nuevo Laredo". CNN México (in Spanish). 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 59 reos en Nuevo Laredo". El Universal (in Spanish). 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 59 reos en Nuevo Laredo tras enfrentamiento". Terra Noticias (in Spanish). 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Tras las fugas de reos en Tamaulipas, el gobierno federal se defiende". CNN Mexico (in Spanish). 7 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Huyen ocho internos de penal en Tenancingo". El Universal (in Spanish). 19 April 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Narco libera reos en Zacatecas". CNN Expansion (in Spanish). 16 May 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ "Investigan fuga de 3 reos de penal en Oaxaca". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). 13 July 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Catean penal de Morelos". El Universal (in Spanish). 14 July 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 5 reos peligrosos de penal en Cancún". El Universal (in Spanish). 5 January 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 10 reos del penal Aquiles Serdán, de Chihuahua". Milenio (in Spanish). 11 January 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Reportan fuga de reos de cárcel de Ahualulco de Mercado". El Informador (in Spanish). 27 March 2011. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Reportan extraña fuga de reos en Sinaloa". El Universal (in Spanish). 10 March 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Escapan cuatro reos de penal de Culiacán". Animal Politico (in Spanish). 2 January 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 32 reos de tres penales de Veracruz". Televisa (in Spanish). 19 September 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Alertan a estados por fuga de 11 reos en Puebla". El Universal (in Spanish). 27 November 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Rebelión en el penal de Cancún deja 3 muertos y 21 lesionados". La Jornada (in Spanish). 9 December 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Se fugan 10 reos de penal en Zacatecas". El Universal (in Spanish). 28 April 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ^ "Más de 400 reos se fugaron de cárceles de Tamaulipas en 14 meses". CNN México (in Spanish). 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Chapa, Sergio (15 October 2011). "20 inmates killed, 12 wounded in Matamoros prison brawl". Valley Central. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Prison riot in Matamoros kills 20; shootouts reported in Reynosa". The Monitor. 16 October 2011. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Chapa, Sergio (8 August 2010). "14 prisoners killed in Matamoros prison brawl". Valley Central. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Pérez González, Jorge (22 February 2009). "Mentes perversas". Hoy Tamaulipas (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ Vindell, Tony (24 January 1996). "El Profe welcomes Garcia Abrego's downfall". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ Althaus, Dudley (2009). "Texas-Mexico Borderlands: The Slide Toward Chaos" (PDF). The International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education. 12 (10974911): 57. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Mexico jail riot 'leaves 21 dead'". BBC News. 20 October 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Mexico prison shooting: 17 dead in Ciudad Juarez clash". BBC News. 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Many killed in Mexico prison violence". Al Jazeera. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Al menos 17 personas mueren durante un motín en una prisión de Juárez". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Pelea en el penal de Cadereyta deja 7 reos muertos y 12 heridos". La Jornada (in Spanish). 14 October 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Mexico Prison Fight: 31 Killed in Altamira". HuffPost. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "31 killed in Mexican prison fight between rival drug gangs". The Global Post. 5 January 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Riña en el penal de Gómez Palacio; 19 muertos". La Jornada (in Spanish). 15 August 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Riña en penal de Durango deja 23 muertos; no descartan ejecuciones". La Jornada (in Spanish). 21 January 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Una balacera en un penal de Durango deja ocho reos muertos y 11 heridos". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 19 May 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "Un grupo de hombres ataca con granada a penal de Durango". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 15 November 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "Confirman 19 muertos por motín en cárcel de Tijuana". El Universal (in Spanish). 18 September 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Suman 29 los reos muertos por violencia en el penal de Mazatlán". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 14 June 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "¿Dónde quedaron los dos jefes zeta que estaban presos en Apodaca?". Animal Político (in Spanish). 23 February 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ "El Gobierno federal construye 10 penales para solucionar crisis carcelaria". CNNMexico (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Garcia, Luis (21 February 2012). "Medina afirma tener control sobre penales de Nuevo León". Milenio (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Urgen descongelar reforma para frenar riñas en cárceles: PAN". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Piden PT y PRD en Senado informe por tragedia en penal de Apodaca". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "PVEM propone reforma integral en cárceles". El Universal (in Spanish). 23 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Exigen renuncias en NL tras matanza en Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "NL podría caer en total anarquía: presidente del Consejo para la Seguridad". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Alerta en Coahuila por posible paso de fugados de Apodaca". El Universal (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Activan alerta en Tamaulipas por prófugos del penal de Apodaca". Milenio (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Buscan en San Luis Potosí a reos fugados en Apodaca, NL". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Solicita ONU a México indagar enfrentamiento y evasión en Apodaca". La Jornada (in Spanish). 21 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "DOCUMENT – MEXICO: FEAR FOR SAFETY / PRISON CONDITIONS". Amnesty International. Retrieved 5 April 2012.