It has been suggested that this article be split into articles titled Anmatyerr language, Western Arrarnta language, Alyawarra language and Ayerrerenge language. (Discuss) (November 2024) |

| Upper Arrernte | |

|---|---|

| Arrernte | |

| Pronunciation | [aɾəⁿɖə] |

| Native to | Australia |

| Region | Northern Territory |

| Ethnicity | Arrernte people, Alyawarre, Anmatyerre, Ayerrereng, Yuruwinga |

Native speakers | 4,100 (2021 census)[1] |

Pama–Nyungan

| |

| Latin | |

| Arrernte Sign Language | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:amx – Anmatjirraaly – Alyawarradg – Antekerrepenheaer – Eastern Arrernteare – Western Arrernteaxe – Ayerrerenge |

| Glottolog | aran1263 |

| AIATSIS[2] | C8 Arrernte, C14 Alyawarr, C8.1 Anmatyerre, C12 Antekerrepenh, G12 Ayerrerenge, C28 Akarre |

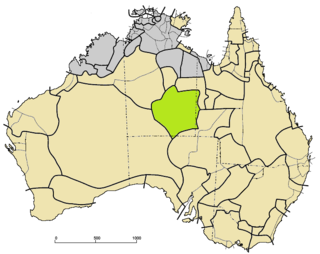

Map of where Arandic is spoken | |

Arrernte is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Arrernte or Aranda (/ˈʌrəndə/;[3] Eastern Arrernte pronunciation: [aɾəⁿɖə]), or sometimes referred to as Upper Arrernte (Upper Aranda), is a dialect cluster in the Arandic language group spoken in parts of the Northern Territory, Australia, by the Arrernte people. Other spelling variations are Arunta or Arrarnta, and all of the dialects have multiple other names.

There are about 1,800 speakers of Eastern/Central Arrernte, making this dialect one of the widest spoken of any Indigenous language in Australia, the one usually referred to as Arrernte and the one described in detail below. It is spoken in the Alice Springs area and taught in schools and universities, heard in media and used in local government.

The second biggest dialect in the group is Alyawarre. Some of the other dialects are spoken by very few people, leading to efforts to revive their usage; others are now completely extinct.

Arrernte/Aranda dialects

[edit]

"Aranda" is a simplified, Australian English approximation of the traditional pronunciation of the name of Arrernte [ˈarəɳ͡ɖa].[4]

Glottolog defines the Arandic group of languages/dialects as comprising 5 Aranda (Arrernte) dialects, plus two distinct languages, Kaytetye (Koch, 2004) and Lower Southern (or just Lower) Aranda, an extinct language.[5] Ethnologue defines 8 Arandic languages and classifies them slightly differently.[6]

Two dialects are more widely spoken than any of the others:

- Eastern Arrernte (also known as Central Arrernte) dialects include Akarre, Antekerrepenh, Ikngerripenhe, Mparntwe Arrernte.[7] Spoken in the Alice Springs area and others, there were 1,910 speakers in the 2016 census,[8] making it the most widely spoken Arrernte, and Australian Aboriginal, language. This is the dialect most often referred to as "Arrernte" and the strongest of all in the group. There is a project encouraging its use, Apmere angkentye-kenhe,[9]

- The Alyawarra dialect is spoken by the Alyawarra people, in the Sandover and Tennant Creek areas as well as Queensland. In 2016 there were 1,550 speakers of the language, giving it a status of "Developing".[10] It is similar to Western Arrernte. (Kaytetye is related to this dialect, but is classed as a separate language.[11])

All of the other dialects are either threatened or extinct:

- Andegerebinha (or Antekerrepenhe or Ayerrerenge) was spoken in the Hay River area (east of Alice Springs), but is now extinct.[12]

- Ayerrerenge, (also known as Yuruwinga, Bularnu and other variations) was spoken by the Yuruwinga/Yaroinga people[13] is the north-easternmost member of the Arrernte group of languages, and the least studied.[11] It was spoken across the Queensland border in the Headingly, Urandangi, Lake Nash, Barkly Downs and Mount Isa areas, and near Mount Hogarth, Bathurst,[14] and Argadargada[15] in the NT.[16] It is now extinct.[16][a] Breen (2001) says that the language was regarded as the same or similar to Andegerebinha/Antekerrepenhe by some speakers,[11] and Glottolog regards it as a dialect of it.[12]

- Anmatyerr (also spelt Anmatyerre and other variations),[17] divided into Eastern and Western, is spoken by the Anmatyerr (or Anmatjirra) people.[18] The Eastern form seems more closely related to Eastern Arrernte and Southern Alywarre than Western Anmatyerre, which is noticeably different phonetically from other Arandic languages.[11] it is spoken in the Mount Allan and northwest Alice Springs regions. With only 640 speakers in the 2016 census, it is regarded as threatened.[19]

- Western Arrarnta (Western Arrernte, Western Aranda, Akara, Southern Aranda, possible sub-dialect Akerre[20]), spoken west of Alice Springs, is nearly extinct, being only spoken by 440 people in 2016.[21] Other terms are Tyuretye Arrernte and Arrernte Alturlerenj.[22][b][c] Breen distinguishes Tyurretye Arrernte (which he initially called Mbunghara) from Western Arrernte, saying that two speakers first recorded, from the Standley Chasm and Mbunghara, was not known until the mid-1980s, and that it may have been the "real" Western Arrernte, before the latter was mixed with Southern Arrernte (Pertame) at the Hermannsburg Mission.[11] Anna Kenny has noted that the people of the Upper Finke River prefer their language to be known as Western Aranda.[25] This dialect has similarities with Alyawarre and Kaytetye.

Sign language

[edit]The Arrernte also have a highly developed Arrernte sign language,[26] also known as Iltyeme-iltyeme.

There is also an Anmatyerr sign language called iltyem-iltyem which is used by many Anmatyerr speakers to communicate non-verbally; the word iltja means 'hand, finger' and the term translates as 'signaling with hands'.[27][28] Sign language is used when Anmatyerr people when hunting, when talking to the deaf, when somebody passes away and when talking to elders.[29]

Current usage and tuition

[edit]The Northern Territory Department of Education has a program for teaching Indigenous culture and languages, underpinned by a plan entitled Keeping Indigenous Languages and Cultures Strong – A Plan for Teaching and Learning of Indigenous Languages and Cultures in the Northern Territory with the second stage of the plan running from 2018 to 2020.[30][31]

The Alice Springs Language Centre delivers language teaching at primary, middle and senior schools, offering Arrernte, Indonesian, Japanese, Spanish and Chinese.[32]

There are two courses teaching Arrernte at tertiary level: at the Batchelor Institute and at Charles Darwin University.[33]

There are books available in Arandic languages in the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages.[34]

Projects are being run to revive dying dialects of the language, such as Southern Arrernte/Pertame.[35]

Eastern/Central Arrernte

[edit]This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used - notably aer for Eastern Arrernte. (November 2024) |

This description relates to Central or Eastern Arrernte.

Phonology

[edit]Consonants

[edit]| Peripheral | Coronal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laminal | Apical | ||||||

| Bilabial | Velar | Uvular | Palatal | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | |

| Stop | p pʷ | k kʷ | c cʷ | t̪ t̪ʷ | t tʷ | ʈ ʈʷ | |

| Nasal | m mʷ | ŋ ŋʷ | ɲ ɲʷ | n̪ n̪ʷ | n nʷ | ɳ ɳʷ | |

| Prestopped nasal | ᵖm ᵖmʷ | ᵏŋ ᵏŋʷ | ᶜɲ ᶜɲʷ | ᵗn̪ ᵗn̪ʷ | ᵗn ᵗnʷ | ᵗɳ ᵗɳʷ | |

| Prenasalized stop | ᵐb ᵐbʷ | ᵑɡ ᵑɡʷ | ᶮɟ ᶮɟʷ | ⁿd̪ ⁿd̪ʷ | ⁿd ⁿdʷ | ⁿɖ ⁿɖʷ | |

| Lateral | ʎ ʎʷ | l̪ l̪ʷ | l lʷ | ɭ ɭʷ | |||

| Approximant | β̞ | ɰ ~ ʁ̞ | j jʷ | ɻ ɻʷ | |||

| Tap | ɾ ɾʷ | ||||||

/ɰ ~ ʁ̞/ is described as velar [ɰ] by Breen & Dobson (2005), and as uvular [ʁ̞] by Henderson (2003).

Stops are unaspirated.[36] Prenasalized stops are voiced throughout; prestopped nasals are voiceless during the stop. These sounds arose as normal consonant clusters; Ladefoged states that they now occur initially, where consonant clusters are otherwise forbidden, due to historical loss of initial vowels;[37] however, it has also been argued that such words start with a phonemic schwa, which may not be pronounced (see below).

Vowels

[edit]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | (i) | (u) | |

| Mid | ə | ||

| Low | a |

All dialects have at least /ə a/.

The vowel system of Eastern/Central Arrernte is unusual in that there are only two contrastive vowel phonemes, /a/ and /ə/. Two-vowel systems are very rare worldwide, but are also found in some Northwest Caucasian languages. It seems that the vowel system derives from an earlier one with more phonemes, but after the development of labialised consonants in the vicinity of round vowels, the vowels lost their roundedness/backness distinction, merging into just two phonemes. There is little allophonic variation in different consonantal contexts for the vowels. Instead, the phonemes can be realised by various different articulations in free variation. For example, the phoneme /ə/ can be pronounced [ɪ ~ e ~ ə ~ ʊ] in most contexts. However, it is required to be [ʊ] when phrase-initial before a labialized consonant (see below).[38]

Phonotactics

[edit]The underlying syllable structure of Eastern/Central Arrernte is argued to be VC(C), with obligatory codas and no onsets.[39] Underlying phrase-initial /ə/ is realised as zero, except before a rounded consonant where, by a rounding process of general applicability, it is realised as [ʊ]. It is also common for phrases to carry a final [ə] corresponding to no underlying segment.[40]

Among the evidence for this analysis is that some suffixes have suppletive variants for monosyllabic and bisyllabic bases. Stems that appear monosyllabic and begin with a consonant in fact select the bisyllabic variant. Stress falls on the first nucleus preceded by a consonant, which by this analysis can be stated more uniformly as the second underlying syllable. And the frequentative is formed by reduplicating the final VC syllable of the verb stem; it does not include the final [ə].

Orthography

[edit]Central/Eastern Arrernte orthography does not write word-initial /ə/, and adds an e to the end of every word.[41]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grammar

[edit]

Eastern and Central Arrernte has fairly free word order but tends towards SOV. It is generally ergative, but is accusative in its pronouns. Pronouns may be marked for duality and skin group.[36]

| suffix | gloss |

|---|---|

| +aye | emphasis |

| +ewe | stronger emphasis |

| +eyewe | really strong emphasis |

| +ke | for |

| +le | actor in a sentence |

| +le | instrument |

| +le | location |

| +le-arlenge | together, with |

| +nge | from |

| -akerte | having |

| -arenye | from (origin), association |

| -arteke | similarity |

| -atheke | towards |

| -iperre, -ipenhe | after, from |

| -kenhe | belongs to |

| -ketye | because (bad consequence) |

| -kwenye | not having, without |

| -mpele | by way of, via |

| -ntyele | from |

| -werne | to |

| +ke | past |

| +lhe | reflexive |

| +me | present tense |

| +rre/+irre | reciprocal |

| +tyale | negative imperative |

| +tye-akenhe | negative |

| +tyeke | purpose or intent |

| +tyenhe | future |

| ∅ | imperative |

Pronouns

[edit]

Pronouns decline with a nominative rather than ergative alignment:

| person | number | subject | object | dative | possessive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | singular | ayenge/the | ayenge/ayenhe | atyenge | atyenhe/atyinhe |

| dual | ilerne | ilernenhe | ilerneke | ilernekenhe | |

| plural | anwerne | anwernenhe | anwerneke | anwernekenhe | |

| 2 | singular | unte | ngenhe | ngkwenge | ngkwinhe |

| dual | mpwele | mpwelenhe | mpweleke | mpwelekenhe | |

| plural | arrantherre | arrenhantherre | arrekantherre | arrekantherrenhe | |

| 3 | singular | re | renhe | ikwere | ikwerenhe |

| dual | re-atherre | renhe-atherre renhe-atherrenhe |

ikwere-atherre | ikwere-atherrenhe | |

| plural | itne | itnenhe | itneke | itnekenhe |

Body parts normally require non-possessive pronouns (inalienable possession), though younger speakers may use possessives in this case too (e.g. akaperte ayenge or akaperte atyinhe 'my head').[44]

Examples

[edit]| Arrernte | English |

|---|---|

werte

|

G'day, What's new?

|

Unte mwerre?

|

Are you alright?

|

Urreke aretyenhenge

|

See you later

|

Cultural references

[edit]- Peter Sculthorpe's music theatre work Rites of Passage (1972–1973) is written partly in Arrernte and partly in Latin.

- Western and Southern Arrernte were used in parts of the libretto for Andrew Schultz' and Gordon Williams' Journey to Horseshoe Bend, based on the novel by Ted Strehlow.

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Glottolog: "E17/E18/E19 has a separate entry for Ayerrerenge [axe]. But Ayerrerenge is an Arandic variety subsumed under the entry Andegerebinha [adg] (Breen, Gavan 2001, Breen, J. Gavan 1971)".

- ^ In Western Arrernte lands the preferred spelling for their language is 'Arrarnta' or 'Aranda'.[23]

- ^ 'The Arandic group whose culture Carl Strehlow documented in great detail identify themselves today as Western Aranda or Arrarnta. They call themselves sometimes Tyurretyerenye, meaning 'belonging to Tyurretye', and refer to their Arandic dialect as Western or Tyurretye Arrernte.'[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021). "Cultural diversity: Census". Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ C8 Arrernte at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (see the info box for additional links)

- ^ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh; also /əˈrændə/ "Aranda". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Turpin 2004.

- ^ "Arandic". Glottolog. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Arandic". Ethnologue. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Ikngerripenhe". Glottolog. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "Eastern Arrernte". Ethnologue. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Home page". Apmere angkentye-kenhe. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "Alyawarr". Ethnologue. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Breen, Gavan (2001). "Chapter 4: The wonders of Arandic phonology" (pdf). In Simpson, Jane; Nash, David; Laughren, Mary; Austin, Peter; Alpher, Barry (eds.). Forty years on: Ken Hale and Australian languages. Pacific Linguistics 512. ANU. Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. (Pacific Linguistics). pp. 45–69. ISBN 085883524X.

- ^ a b "Andegerebinha". Glottolog. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "G12: Ayerrerenge". Austlang. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ NOTE: Cannot find reference to a Bathurst in this region, but this map of Mt Hogarth shows a "Bathurst Bore".

- ^ "Argadargada Waterhole (with map)". Bonzle. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Ayerrerenge". Ethnologue. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ C8.1 Anmatyerr at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ^ "Anmatyerre". Glottolog. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "Anmatyerre". Ethnologue. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Akerre". Glottolog. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "Western Arrarnte". Ethnologue. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Dixon 2002, p. xxxix.

- ^ Kenny 2017, p. xvii.

- ^ Kenny 2017, p. 6.

- ^ Kenny, Anna (17 November 2017). "Aranda, Arrernte or Arrarnta? The Politics of Orthography and Identity on the Upper Finke River". Oceania. 87 (3): 261–281. doi:10.1002/ocea.5169.

- ^ Kendon 1988, pp. 49–50.

- ^ "Iltyem-iltyem – Australian Indigenous Sign Languages". www.iltyemiltyem.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Iltyem-iltyem Indigenous Sign Languages of Central Australia". Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Central Australian Aboriginal sign language shared in Tasmania". ABC News. 22 April 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Northern Territory Government, April 2018.

- ^ Northern Territory Government 2017.

- ^ Schools.

- ^ ULPA search.

- ^ Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages.

- ^ Pertame Project.

- ^ a b Green (2005).

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 129. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

- ^ Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996)

- ^ Breen & Pensalfini (1999).

- ^ Breen & Pensalfini (1999), pp. 2–3.

- ^ "Arrernte language, alphabet and pronunciation". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ Green (2005), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Green (2005), p. 54.

- ^ Green (2005), p. 55.

- ^ "Fact Sheet 3" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009. (681 KB)

Sources

[edit]- Breen, Gavan (2000). Introductory Dictionary of Western Arrernte. Alice Springs: IAD Press. ISBN 978-0-949659-98-9.

- Breen, Gavan (2001). "The wonders of Arandic phonology". In Simpson, Jane; Nash, David; Laughren, Mary; Austin, Peter; Alpher, Barry (eds.). Forty Years On: Ken Hale and Australian Languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 45–69.

- Breen, Gavan; Dobson, Veronica (2005). "Illustrations of the IPA: Central Arrernte". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 249–254. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002185.

- Breen, Gavan; Pensalfini, Rob (1999). "Arrernte: A Language with No Syllable Onsets" (PDF). Linguistic Inquiry. 30 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1162/002438999553940. S2CID 57564955.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47378-1.

- Green, Jenny (2005). A learner's guide to Eastern and Central Arrernte. Alice Springs: IAD Press. ISBN 978-1-86465-081-5.

- Henderson, John (1988). Topics in Eastern and Central Arrernte grammar. PhD dissertation. University of Western Australia.

- Henderson, John; Veronica Dobson (1994). Eastern and Central Arrernte to English Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press. ISBN 978-0-949659-74-3.

- Henderson, John (2003). "The word in Eastern/Central Arrernte". In R. M. W. Dixon; Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (eds.). Word: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 100–124.

- Kendon, Adam (1988). Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia: Cultural, Semiotic and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36008-1.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Ian Maddieson (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- "Lower Arrernte". Mobile Language Team. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Mathews, R. H. (October–December 1907). "The Arran'da Language, Central Australia". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 46 (187): 322–339.

- Northern Territory Government. Dept of Education (5 April 2018). "Indigenous Education Strategy - Issue 17: Keeping Arrernte strong". NT Government.

- Northern Territory Government. Dept of Education (2017). "Guidelines for the implementation of Indigenous languages and cultures programs in schools" (PDF). NT Government.

- "Pertame Project". Call for Australian languages and linguistics. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- "Schools". Alice Springs Language Centre. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Strehlow, T. G. H. (1944). Aranda phonetics and grammar. Sydney: Oceania Monographs.

- "To save a dying language". Alice Springs News Online. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Turpin, Myfany (August 2004). "Have you ever wondered why Arrernte is spelt the way it is?". Central Land Council.

- "ULPA search". University Languages Portal Australia.

- "LAAL". Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Wilkins, David P. (1988). "Switch-reference in Mparntwe Arrernte (Aranda): form, function, and problems of identity". In Austin, P. K. (ed.). Complex sentence constructions in Australian languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 141–176.

- Wilkins, David P. (1989). Mparntwe Arrernte (Aranda): studies in the structure and semantics of grammar. PhD dissertation, Australian National University.

- Wilkins, David P. (1991). "The semantics, pragmatics and diachronic development of "associated motion" in Mparntwe Arrente". Buffalo Working Papers in Linguistics. 91: 207–257.

- Yallop, C. (1977). Alyawarra, an Aboriginal language of central Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. ISBN 978-0-85575-062-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Arrernte: Data collected on the Arrernte language (Sorosoro program for linguistic diversity, 2015)

- Arrernte (Arrernte angkentye) (Omniglot.com)

- Arrernte language - with map. (Aboriginal Art and Culture, Alice Springs)

- Gavan Breen Eastern Arrernte collection - written materials (PARADISEC open-access collection)

- Green, Jenny (Jennifer Anne); Institute for Aboriginal Development (Alice Springs, N.T.) (1992), Alyawarr to English dictionary, Institute for Aboriginal Development, ISBN 978-0-949659-66-8

- Kimber, Richard (2009). "Chapter 13. Placenames of central Australia: Early European records and recent experience". In Harold Koch; Luise Hercus (eds.). Aboriginal Placenames: Naming and re-naming the Australian landscape. Aboriginal History Monograph. Australian National University. Aboriginal History Incorporated. p. 23. ISBN 9781921666087. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Keeping The Aboriginal Language Strong (The Spoken Word)

- Published Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, rare items Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine and special materials Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine on Arrernte language and people: bibliographies of items held in the AIATSIS library

- Roennfeldt, David. "Western Arrarnta picture dictionary". Trove. Compiled by David Roennfeldt with members of the communities of Ntaria, Ipolera, Gilbert Springs, Kulpitarra, Undarana, Red Sand Hill, Old Station and other outstations. - Version details.