Aunt Jemima was an American breakfast brand for pancake mix, table syrup, and other breakfast food products. The original version of the pancake mix was developed in 1888–1889 by the Pearl Milling Company and was advertised as the first "ready-mix" cooking product.[1][2]

Aunt Jemima was modeled after, and has been a famous example of, the "Mammy" archetype in the Southern United States.[3] Due to the "Mammy" stereotype's historical ties to the Jim Crow era, Quaker Oats announced in June 2020 that the Aunt Jemima brand would be discontinued "to make progress toward racial equality",[4] leading to the Aunt Jemima image being removed by the fourth quarter of 2020.[5]

In June 2021, amidst heightened racial unrest in the United States,[6] the Aunt Jemima brand name was discontinued by its current owner, PepsiCo, with all products rebranded to Pearl Milling Company, the name of the company that produced the original pancake mix product.[5][7][8] The Aunt Jemima name remains in use in the brand's tagline, "Same great taste as Aunt Jemima."[5]

Nancy Green portrayed the Aunt Jemima character at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and was one of the first Black corporate models in the United States.[1] Subsequent advertising agencies hired dozens of actresses to perform the role as the first organized sales promotion campaign.[9][10]

History

[edit]In 1888, St. Joseph Gazette editor Chris L. Rutt and his friend Charles G. Underwood bought a small flour mill at 214 North 2nd St. in St. Joseph, Missouri.[11] Rutt and Underwood's "Pearl Milling Company" produced a range of milled products (such as wheat flour and cornmeal) using a pearl milling process.[12] Facing a glutted flour market, after a year of experimentation they began selling their excess flour in paper bags with the generic label "Self-Rising Pancake Flour" (later dubbed "the first ready-mix").[1][2][13]

Branding and trademark

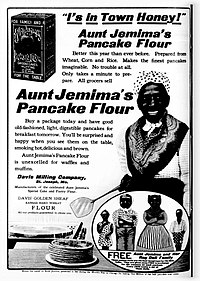

[edit]To distinguish their pancake mix, in late 1889 Rutt appropriated the Aunt Jemima name and image from lithographed posters seen at a vaudeville house in St. Joseph, Missouri.[1][13] Aunt Jemima was portrayed by Nancy Green, a former slave, of Montgomery County, Kentucky.[14]

In 1915, the well-known Aunt Jemima brand was the basis for a trademark law ruling that set a new precedent. Previously, United States trademark law had protected against infringement by other sellers of the same product, but under the "Aunt Jemima Doctrine", the seller of pancake mix was also protected against infringement by an unrelated seller of a different but related product—pancake syrup.[15] Aunt Jemima became one of the longest continually running logos and trademarks in the history of American advertising.[16]

Logo

[edit]

The earliest advertising was based upon a vaudeville parody, and it remained a caricature for many years.[1][3][13]

Quaker Oats commissioned Haddon Sundblom, a nationally known commercial artist, to paint a portrait of an obese actress named Anna Robinson, and the Aunt Jemima package was redesigned around the new likeness.[1][17]

James J. Jaffee, a freelance artist from the Bronx, New York, also designed one of the images of Aunt Jemima used by Quaker Oats to market the product into the mid-20th century.

Just as the formula for the mix changed several times over the years, so did the Aunt Jemima image. In 1968, the face of Aunt Jemima became a composited creation. She was slimmed down from her previous appearance, depicting a more "svelte" look, wearing a white collar and a geometric print "headband" still resembling her previous kerchief.[1][18][19][20]

In 1989, marking the 100th anniversary of the brand, her image was again updated, with all head-covering removed, revealing wavy, gray-streaked hair, gold-trimmed pearl earrings, and replacing her plain white collar with lace. At the time, the revised image was described as a move towards a more "sophisticated" depiction, with Quaker marketing the change as giving her "a more contemporary look" which remained on the products until early 2021.[18][19]

Rebranding of 2020–2021

[edit]On June 17, 2020, Quaker Oats announced that the Aunt Jemima brand would be discontinued and replaced with a new name and image "to make progress toward racial equality".[4][21] The image was removed from packaging in fall 2020, while the name change was said to be planned for a later date.[22][23]

Within one day of the June 2020 announcement, other similarly motivated rebrandings and reviews of brand marketing were also announced, including for Uncle Ben's rice (which was renamed Ben's Original), the Mrs. Butterworth's pancake syrup brand and bottle shape, and the "Rastus" Black chef logo used by Cream of Wheat.[7]

Descendants of Aunt Jemima models Lillian Richard and Anna Short Harrington objected to the change. Vera Harris, a family historian for Richard's family, said "I wish we would take a breath and not just get rid of everything. Because good or bad, it is our history."[24] Harris further stated "Erasing my Aunt Lillian Richard would erase a part of history."[25] Harrington's great-grandson Larnell Evans said "This is an injustice for me and my family. This is part of my history." Evans had previously lost a lawsuit against Quaker Oats (and others) for billions of dollars in 2015.[26]

On February 9, 2021, PepsiCo announced that the replacement brand name would be Pearl Milling Company. PepsiCo purchased that brand name for that purpose on February 1, 2021.[7] The new branding was launched that June, one year after the company announced they would drop Aunt Jemima branding. PepsiCo referenced the Aunt Jemima brand by logotype on the front of the packaging for at least six months after the rebrand. Following that period, PepsiCo said it wouldn't be able to completely permanently abandon the Aunt Jemima brand due to trademark law; if it did, a third party could obtain and use the brand.[5]

Character of Aunt Jemima

[edit]

Aunt Jemima is based on the common enslaved "Mammy" archetype, a plump black woman wearing a headscarf who is a devoted and submissive servant.[3][16] Her skin is dark and dewy, with a pearly white smile. Although depictions vary over time, they are similar to the common attire and physical features of "mammy" characters throughout American history.[27][28][29][30][31][32]

The term "aunt" and "uncle" in this context was a Southern form of address used with older enslaved peoples. They were denied use of English honorifics, such as "mistress" and "mister".[33][34]

A British image in the Library of Congress, which may have been created as early as 1847, shows a smiling black woman named "Miss Jim-Ima Crow", with a framed image of "James Crow" on the wall behind her.[35] A character named "Aunt Jemima" appeared on the stage in Washington, D.C., as early as 1864.[36] Rutt's inspiration for Aunt Jemima was Billy Kersands' American-style minstrelsy/vaudeville song "Old Aunt Jemima", written in 1875. Rutt reportedly saw a minstrel show featuring the "Old Aunt Jemima" song in the fall of 1889, presented by blackface performers identified by Arthur F. Marquette as "Baker & Farrell".[13] Marquette recounts that the actor playing Aunt Jemima wore an apron and kerchief.[13][34]

However, Doris Witt at University of Iowa was unable to confirm Marquette's account.[17] Witt suggests that Rutt might have witnessed a performance by the vaudeville performer Pete F. Baker, who played characters described in newspapers of that era as "Ludwig" and "Aunt Jemima". His portrayal of the Aunt Jemima character may have been a white male in blackface, pretending to be a German immigrant, imitating a black minstrel parodying an imaginary black female enslaved cook.[17]

Advertising

[edit]Marketing materials for the line of products centered around the "Mammy" archetype, including the slogan first used at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois: "I's in Town, Honey".[3][17][37]

At that World's Fair, and for decades afterward,[34] marketers created and circulated fictional stories about Aunt Jemima.[9] She was presented as a "loyal cook" for a fictional Colonel Higbee's Louisiana plantation on the Mississippi River.[9][37][38][39] Jemima was said to use a secret recipe "from the South before the Civil War", with their "matchless plantation flavor", to make the best pancakes in Dixie.[34][38] Another story described her as diverting Union soldiers during the Civil War with her pancakes long enough for Colonel Higbee to escape.[37] She was said to have revived a group of shipwrecked survivors with her flapjacks.[9]

Beginning in 1894, the company added an Aunt Jemima paper doll family that could be cut out from the pancake box.[38] Aunt Jemima is joined by her husband, Uncle Rastus (later renamed Uncle Mose to avoid confusion with the Cream of Wheat character, while Uncle Mose was first introduced as the plantation butler).[40] Their children, described as "comical pickaninnies": Abraham Lincoln, Dilsie, Zeb, and Dinah. The paper doll family was posed dancing barefoot, dressed in tattered clothing, and the box was labeled "Before the Receipt was sold". (Receipt is an archaic rural form of recipe.)[38] Buying another box with elegant clothing cut-outs to fit over the dolls, the customer could transform them "After the Receipt was sold". This placed them in the Horatio Alger rags-to-riches American cultural mythos.[38]

Rag doll versions were offered as a premium in 1909: "Aunt Jemima Pancake Flour / Pica ninny Doll / The Davis Milling Company". Early versions were portrayed as poor people with patches on their trousers, large mouths, and missing teeth. The children's names were changed to Diana and Wade. Over time, there were improvements in appearance. Oil-cloth versions were available circa the 1950s, with cartoonish features, round eyes, and watermelon mouths.[41]

A typical magazine ad from the turn of the century created by advertising executive James Webb Young, and the illustrator N.C. Wyeth,[37] shows a heavyset black cook talking happily while a white man takes notes. The ad copy says, "After the Civil War, after her master's death, Aunt Jemima was finally persuaded to sell her famous pancake recipe to the representative of a northern milling company."[9]

However, the Davis Milling Company was not located in a northern state. Missouri in the American Civil War was a hotly contested border state. In reality, she never existed, created by marketers to better sell products.[32]

Controversy

[edit]

Although the Aunt Jemima character was not created until nearly 25 years after the American Civil War, the clothing, dancing, enslaved dialect, and singing old plantation songs as she worked, all harkened back to a glorified view of antebellum Southern plantation life as a "happy slave" narrative.[32][38] The marketing legend surrounding Aunt Jemima's successful commercialization of her "secret recipe" contributed to the post-Civil War nostalgia and romanticism of Southern life in service of America's developing consumer culture—especially in the context of selling kitchen items.[3][16][30]

African American women formed the Women's Columbian Association and the Women's Columbian Auxiliary Association to address the exclusion of African Americans from the 1893 World's Fair exhibitions, asking that the fair reflect the success of post-Emancipation African Americans.[38] Instead, the Fair included a miniature West African village whose natives were portrayed as primitive savages.[37] Ida B. Wells was incensed by the exclusion of African Americans from mainstream fair activities; the so-called "Negro Day" was a picnic held off-site from the fairgrounds.[38]

Black scholars Hallie Quinn Brown, Anna Julia Cooper, and Fannie Barrier Williams used the World's Fair as an opportunity to address how African American women were being exploited by white men.[38][42] In her book A Voice from the South (1892), Cooper had noted the fascination with "Southern influence, Southern ideas, and Southern ideals" had "dictated to and domineered over the brain and sinew of this nation".[38]

These educated progressive women saw "a mammy for the national household" represented at the World's Fair by Aunt Jemima.[38] This directly relates to the belief that slavery cultivated innate qualities in African Americans. The notion that African Americans were natural servants reinforced a racist ideology renouncing the reality of African American intellect.[38]

Aunt Jemima embodied a post-Reconstruction fantasy of idealized domesticity, inspired by "happy slave" hospitality, and revealed a deep need to redeem the antebellum South.[38] There were others that capitalized on this theme, such as Uncle Ben's Rice and Cream of Wheat's Rastus.[34][38]

Slang

[edit]The term "Aunt Jemima" is sometimes used colloquially as a female version of the derogatory epithet "Uncle Tom" or "Rastus". In this context, the slang term "Aunt Jemima" falls within the "mammy archetype" and refers to a friendly black woman who is perceived as obsequiously servile or acting in, or protective of, the interests of whites.[43]

John Sylvester of WTDY-AM drew criticism after calling Condoleezza Rice an "Aunt Jemima" and Colin Powell an "Uncle Tom", referring to remarks by singer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte about their alleged subservience in the George W. Bush administration. He apologized by giving away Aunt Jemima's pancake mix and syrup.[44]

Barry Presgraves, then 77-year-old Mayor of Luray, Virginia, was censured 5-to-1 by the town council because he referred to Kamala Harris as "Aunt Jemima" after she was selected by Joe Biden to be the Democratic Party vice presidential candidate.[45][46][47][48]

Performers of Aunt Jemima

[edit]The African American Registry of the United States suggests Nancy Green and others who played the caricature of Aunt Jemima[23] should be celebrated despite what has been widely condemned as a stereotypical and racist brand image. The registry wrote, "We celebrate the birth of Nancy Green in 1834. She was a Black storyteller and one of the first Black corporate models in the United States."[49]

Following Green's work as Aunt Jemima, very few were well-known. Advertising agencies (such as J. Walter Thompson, Lord and Thomas, and others) hired dozens of actors to portray the role, often assigned regionally, as the first organized sales promotion campaign.[1][9]

Quaker Oats ended local appearances for Aunt Jemima in 1965.[50]

Nancy Green

[edit]Nancy Green was the first spokesperson hired by the R. T. Davis Milling Company for the Aunt Jemima pancake mix.[2] Green was born into slavery in Montgomery County, Kentucky.[1][51] Dressed as Aunt Jemima, Green appeared at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, beside the "world's largest flour barrel" (24 feet high), where she operated a pancake-cooking display, sang songs, and told romanticized stories about the Old South (a happy place for blacks and whites alike). She appeared at fairs, festivals, flea markets, food shows, and local grocery stores, her arrival heralded by large billboards featuring the caption, "I'se in town, honey."[1][3][51]

Green refused to cross the ocean for the 1900 Paris exhibition.[17][52] She was replaced by Agnes Moody. Green died in 1923 and was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave in Chicago's Oak Woods Cemetery.[37][52][53][54] A headstone was placed on September 5, 2020.[55]

Agnes Moody

[edit]60-year-old Agnes Moody first performed as Aunt Jemima at the 1900 Paris exhibition, and was erroneously reported as the original Aunt Jemima.[56][57] She had become well known in the Chicago area for her cornmeal bread and cakes. She died April 9, 1903.[57]

Lillian Richard

[edit]

Lillian Richard was hired to portray Aunt Jemima in 1925, and remained in the role for 23 years. Richard was born in 1891, and grew up in the tiny community of Fouke 7 miles west of Hawkins in Wood County, Texas. In 1910, she moved to Dallas, working initially as a cook. Her job "pitching pancakes" was based in Paris, Texas.[9] After she suffered a stroke circa 1947–1948, she returned to Fouke, where she lived until her death in 1956. Richard was honored with a Texas Historical Marker in her hometown, dedicated in her name on June 30, 2012.[58][59][60][61]

Hawkins, Texas, east of Mineola, is known as the "Pancake Capital of Texas" because of longtime resident Lillian Richard. The local chamber of commerce decided to use Hawkins' connection to Aunt Jemima to boost tourism.[58] In 1995, State Senator David Cain introduced Senate Resolution No. 73 designating Hawkins as the "Pancake Capital of Texas", which was passed into law; the measure was spearheaded by Lillian's niece, Jewell Richard-McCalla.[9]

Artie Belle McGinty

[edit]In 1927, Artie Belle McGinty debuted as the original radio advertisement voice for Aunt Jemima.[62]

Anna Robinson

[edit]

Anna Robinson was hired to play Aunt Jemima at the 1933 Century of Progress Chicago World's Fair.[2][13] Robinson answered an open audition, and her appearance was more like the "mammy" stereotype than the slender Lillian Richard.[17] Born circa 1899, she was also from Kentucky and widowed (like Green), but in her 30s with 8 years of education.[63] She was sent to New York City by Lord and Thomas to have her picture taken. A 1967 company history commemorated this journey as "the day they loaded 350 pounds of Anna Robinson on the Twentieth Century Limited."[13]

She appeared at prestigious establishments frequented by the rich and famous, such as El Morocco, the Stork Club, "21", and the Waldorf-Astoria.[1][63] Photos show Robinson making pancakes for celebrities and stars of Broadway, radio, and motion pictures. They were used in advertising "ranked among the highest read of their time".[13] The Aunt Jemima packaging was redesigned in her likeness.[1][17]

Robinson reportedly worked for the company until her death in 1951; however, [1][2] the work, which was sporadic and for mere weeks in a year,[63] was not enough to escape the hard life into which she had been born.[63] Her $1,200 total payment in 1939 (equivalent to $26,285 in 2023) was almost the entirety of the household's annual income[63] and stood in stark contrast to the official Aunt Jemima history timeline, which stated that Robinson was "able to make enough money to provide for her children and buy a 22-room house where she rents rooms to boarders".[64] The same claim was made for Anna Short Harrington, yet according to the 1940 census, she rented an apartment in a four-flat in Washington Park with her daughter, son-in-law, and two grandchildren.[63]

Rosa Washington Riles

[edit]Rosa Washington Riles became the third face on Aunt Jemima packaging in the 1930s, and continued until 1948. Rosa Washington was born in 1901 near Red Oak in Brown County, Ohio, one of several children of Robert and Julie (Holliday) Washington and a granddaughter of George and Phoeba Washington.[65] She was employed as a cook in the home of a Quaker Oats executive and began pancake demonstrations at her employer's request. She died in 1969, and is buried near her parents and grandparents in the historic Red Oak Presbyterian Church cemetery of Ripley, Ohio.[65] An annual Aunt Jemima breakfast has been a long-time fundraiser for the cemetery, and the church maintains a collection of Aunt Jemima memorabilia.[33][65][66][67]

Anna Short Harrington

[edit]Anna Short Harrington began her career as Aunt Jemima in 1935 and continued to play the role until 1954. She was born in 1897 in Marlboro County, South Carolina. The Short family lived on the Pegues Place plantation as sharecroppers.[68] In 1927, she moved to Syracuse, New York. Quaker Oats discovered her cooking pancakes at the 1935 New York State Fair.[69][70][71] Harrington died in Syracuse in 1955.[68][69][70][71]

Edith Wilson

[edit]Edith Wilson was the face of Aunt Jemima on radio, television, and in personal appearances, from 1948 to 1966 and was the first Aunt Jemima to appear in television commercials. Born in 1896 in Louisville, Kentucky, Wilson was a classic blues singer and actress in Chicago, New York, and London. She appeared on radio in The Great Gildersleeve, on radio and television in Amos 'n' Andy, and on film in To Have and Have Not (1944). Wilson died in Chicago on March 31, 1981.[1][72]

Ethel Ernestine Harper

[edit]Ethel Ernestine Harper portrayed Aunt Jemima during the 1950s.[1][20] Harper was born on September 17, 1903, in Greensboro, Alabama.[73] After graduating from college at the age of 17, she taught elementary school for 2 years and high school mathematics for 10 years. She then moved to New York City, where she performed in The Hot Mikado in 1939. She also appeared in Harlem Cavalcade in 1942 and toured Europe during and after World War II as one of the Ginger Snaps. Harper, who was the last individual model for the character's logo,[20] died in Morristown, New Jersey on March 31, 1979.[1][74]

Rosie Lee Moore Hall

[edit]Rosie Lee Moore Hall, the last "living" Aunt Jemima, was born in Robertson County, Texas on June 22, 1899. She was working in the Quaker Oats' advertising department in Oklahoma when she answered their search for a new Aunt Jemima. Hall portrayed Aunt Jemima from 1950 until her death (on her way to church) from a heart attack on February 12, 1967. She was buried in the family plot in the Colony Cemetery near Wheelock, Texas. On May 7, 1988, her grave was declared an historical landmark.[1][9]

Aylene Lewis

[edit]Aylene Lewis portrayed Aunt Jemima at the Disneyland Aunt Jemima's Pancake House, a popular eating place at the park on New Orleans Street in Frontierland, from 1957 until her death in 1964. Lewis became well known posing for pictures with visitors and serving pancakes to dignitaries, such as Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. She also developed a close relationship with Walt Disney.[1][13]

In popular culture

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Aunt Jemima has been featured in various formats and settings throughout popular culture. Aunt Jemima has been a present image identifiable by popular culture for well over a century, dating back to Nancy Green's appearance at the 1893 World Fair in Chicago, Illinois.[75]

Aunt Jemima, a minstrel-type variety radio program, was broadcast January 17, 1929 – June 5, 1953, at times on CBS and at other times on the Blue Network. The program had several hiatuses during its time on the air.[76]

The 1933 novel Imitation of Life by Fannie Hurst features an Aunt Jemima-type character, Delilah, a maid struggling in life with her widowed employer, Bea. Their fortunes change dramatically when Bea capitalizes on Delilah's family pancake recipe to open a pancake restaurant that attracts tourists at the Jersey Shore. It became a great success and was eventually packaged and sold as Aunt Delilah's Pancake Mix. They achieve that success due to selling flour with a smiling Delilah on the box dressed in Aunt Jemima fashion. The Academy Award-nominated 1934 film version of Imitation of Life starring Claudette Colbert and Louise Beavers retains this part of the plot, which was excised from the 1959 remake of Imitation of Life starring Lana Turner and directed by Douglas Sirk.

In the 1960s, Betye Saar began collecting images of Aunt Jemima, Uncle Tom, Little Black Sambo, and other stereotyped African-American figures from folk culture and advertising of the Jim Crow era. She incorporated them into collages and assemblages, transforming them into statements of political and social protest.[77] The Liberation of Aunt Jemima is one of her most notable works from this era. In this mixed-media assemblage, Saar utilized the stereotypical mammy figure of Aunt Jemima to subvert traditional notions of race and gender.[78]

"Aunt Jemima's Kitchen"—named Aunt Jemima's Pancake House when it first started operating in 1955—was a restaurant opened in 1962 during the Civil Rights Movement as the official Aunt Jemima restaurant at Disneyland. In addition to the restaurant, a woman portraying Aunt Jemima was poised at the restaurant to take pictures with its patrons.[79] Aunt Jemima's Kitchen also had additional locations across the United States.[80]

The Aunt Jemima character, portrayed at the time by Edith Wilson, received the Key to the City of Albion, Michigan, on January 25, 1964.[81] Actresses portraying Aunt Jemima visited Albion, Battle Creek ("Cereal City"), and other Michigan cities many times over three decades. Grand Rapids had an Aunt Jemima's Kitchen, one of 21 locations, until it was changed to Colonial Kitchen in 1968.[50]

Frank Zappa includes a song titled "Electric Aunt Jemima" on his 1969 album Uncle Meat. Electric Aunt Jemima was the nickname for Zappa's Standel guitar amplifier.[82]

Faith Ringgold's first quilt story Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) depicts the story of Aunt Jemima as a matriarch restaurateur: through mediums of text and imagery used to characterize Aunt Jemima in the public sphere, Ringgold represented the oppressed mammy caricature as an entrepreneur.[83]

"Burn Hollywood Burn" on Public Enemy's 1990 album Fear of a Black Planet features Big Daddy Kane commenting on the updating of racial tropes with the lyrics, "And black women in this profession / As for playin' a lawyer, out of the question / For what they play Aunt Jemima is the perfect term / Even if now she got a perm."[84] Spike Lee's 2000 film Bamboozled features Aunt Jemima (played by Tyheesha Collins) as one of the dancing "pickaninnies" in the film's deliberately racist TV show Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show, alongside other stereotypical black antebellum South characters like Rastus.

The 2004 mockumentary C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America features numerous depictions of Aunt Jemima-type characters as slaves (referred to as servants) in an alternate timeline in which the Confederacy won the American Civil War.[citation needed]

In the South Park episode "Gluten Free Ebola" (2014), Aunt Jemima appears in Eric Cartman's delirious dream to tell him that the food pyramid is upside down.[85]

On November 7, 2020, the comedy sketch TV series Saturday Night Live featured a skit in which Aunt Jemima was fired, in addition to Uncle Ben, with roles played by "Count Chocula" and the "Allstate Guy".[86]

In the 2021 film, Judas and the Black Messiah, a police officer disparagingly compares a passing Black woman to Aunt Jemima, in a scene where Chicago Police are surrounding the Black Panther Party Headquarters.[87]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Kern-Foxworth, Marilyn (1994). Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Rastus: Blacks in advertising, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Aunt Jemima—Our History". Quaker Oats. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f "Caricatures of African Americans: Mammy". Regnery Publishing. November 25, 2012. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Kesslen, Ben (June 17, 2020). "Aunt Jemima brand to change name, remove image that Quaker says is 'based on a racial stereotype'". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Kowitt, Beth (February 11, 2021). "The inside story behind Aunt Jemima's new name". Fortune. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Boyce, Travis (Summer 2020). "Cruel Summer1 | Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy". Journaldialogue.org. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Alcorn, Chauncey (February 9, 2021). "Aunt Jemima finally has a new name". CNN Business. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Kubota, Samantha (February 9, 2021). "Brand formerly known as Aunt Jemima reveals new name". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Crocker, Ronnie (June 17, 2020). "Homage to Aunt Jemima remains a tricky business". Beaumont Enterprise. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020.

- ^ "The untold story of the real 'Aunt Jemima' and the fight to preserve her legacy". ABC News. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ "What is the history of the brand?". contact.pepsico.com. 2021. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "What Does Aunt Jemima's New Name, Pearl Milling Company, Mean?". Outsider. February 10, 2021. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marquette, Arthur F. (1967). Brands, Trademarks, and Good Will: The Story of the Quaker Oats Company. McGraw-Hill. ASIN B0006BOVBM.

- ^ "Nancy Green, The Original 'Aunt Jemima' born". African American Registry.

- ^ Soniak, Matt (June 15, 2012). "How Aunt Jemima Changed U.S. Trademark Law". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c Richardson, Riché (June 24, 2015). "Can We Please, Finally, Get Rid of 'Aunt Jemima'?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Witt, Doris (2004). Black Hunger: Soul Food and America. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4551-0. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Key, Janet (April 28, 1989). "At Age 100, A New Aunt Jemima". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Anderson, Peggy (May 2, 1989). "Aunt Jemima's Ready for the '90s". The Burlington Free Press. Associated Press. p. 7. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c Ingrano, Terrance (February 4, 2019). "Strange But True: 'I'se in town, honey!'". Worcester Telegram. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020.

- ^ Valinsky, Jordan (June 17, 2020). "The Aunt Jemima brand, acknowledging its racist past, will be retired". CNN. Archived from the original on February 11, 2021.

- ^ Kubota, Samantha (June 17, 2020). "Aunt Jemima to remove image from packaging and rename brand". TODAY.com. NBC Universal. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Voytko, Lisette (June 17, 2020). "Aunt Jemima—Long Denounced As A Racist Caricature—Removed By Quaker Oats". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021.

- ^ Hallmark, Bob (June 22, 2020). "Family of woman who portrayed Aunt Jemima opposes move to change brand". KLTV. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020.

- ^ Young, Robin; Hagan, Allison (June 29, 2020). "Family Of Woman Who Portrayed Aunt Jemima Speaks Out About Quaker Oats's Rebranding Decision". WBUR. Boston. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Konkol, Mark (June 18, 2020). "Aunt Jemima's Great-Grandson Enraged Her Legacy Will Be Erased". The Patch. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021.

- ^ Griffin, Johnnie (1998). "Aunt Jemima: Another Image, Another Viewpoint". Journal of Religious Thought. 54/55: 75–77.

- ^ Manring, M. M. (1998). Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima. University of Virginia Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-8139-1811-1.

- ^ Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (June 15, 2009). "Southern Memory, Southern Monuments, and the Subversive Black Mammy". Southern Spaces. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Gritz, Jennie Rothenberg (April 23, 2012). "New Racism Museum Reveals the Ugly Truth Behind Aunt Jemima". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021.

- ^ Zillman, Claire (August 12, 2014). "Why it's so hard for Aunt Jemima to ditch her unsavory past". Fortune. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c Patrick, Jeanette (May 11, 2017). "Aunt Jemima and Betty Crocker: American Cultural Icons that Never Existed". National Women's History Museum. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Berry, Karin D. (June 18, 2020). "It was past time for Aunt Jemima's image to go". Andscape. ESPN. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "The Advertiser's Holy Trinity: Aunt Jemima, Rastus, and Uncle Ben". Moss H. Kendrix: A retrospective. The Museum of Public Relations. Archived from the original on May 7, 2006.

- ^ "Miss Jim-Ima Crow". The Library of Congress. January 1847. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "Daily national Republican. [volume] (Washington, D.C.) 1862–1866, August 11, 1864, Second Edition, Image 3". Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. National Endowment for the Humanities. August 11, 1864. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Roberts, Sam (July 18, 2020). "Overlooked No More: Nancy Green, the 'Real Aunt Jemima'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (1962). "Dishing Up Dixie: Recycling the Old South". Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. University of Michigan Press – Ann Arbor. pp. 58–72. ISBN 978-0-472-11614-0. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021.

- ^ "The Poor Little Bride of 1860". Good Housekeeping. Vol. 70. C.W. Bryan & Company. 1920. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021.

- ^ Dotz, Warren; Morton, Jim (1996). What a Character! 20th Century American Advertising Icons. Chronicle Books. p. 10. ISBN 0-8118-0936-6.

- ^ Lamphier, Mary Jane (January 13, 2020). "Aunt Jemima and family!". collectorsjournal.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020.

- ^ Cooper, Anna Julia (January 28, 2007). "Women's Cause is One and Universal". BlackPast. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020.

Anna Julia Cooper, in May Wright Sewell, ed., The World's Congress of Representative Women (Chicago: Rand, McNally, 1894), pp. 711–715.

- ^ Cassell's Dictionary of Slang, Jonathon Green, Cassell, March 1999, ISBN 0-304-34435-4, p. 36.

- ^ "Radio host Calls Rice 'Aunt Jemima'". NBC News. Associated Press. November 19, 2004. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020.

- ^ Jasper, Simone (August 5, 2020). "Virginia mayor who said Joe Biden picked Aunt Jemima as VP faces calls to resign". McClatchy Washington Bureau. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021.

- ^ Hood, John (August 11, 2020). "Luray mayor apologizes for Facebook post at town council meeting". WHSV-TV. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020.

- ^ Armstrong, Rebecca (August 11, 2020). "Luray Town Council Censures Mayor Over 'Aunt Jemima' Post". Daily News-Record. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020.

- ^ Griffith, Janelle (August 13, 2020). "Virginia mayor urged to resign after saying Biden picked 'Aunt Jemima as his VP'". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Nancy Green, the original "Aunt Jemima"". aaregistry.org. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Buckley, Nick (June 24, 2020). "'Aunt Jemima' was given the key to Albion in 1964. The character, based on a stereotype, is being retired". Battle Creek Enquirer.

- ^ a b Aulbach, Lucas (June 17, 2020). "Aunt Jemima's image pulled from boxes, putting an end to a story that began in Kentucky". Louisville Courier Journal.

- ^ a b Nagasawa, Katherine (June 19, 2020). "The Fight To Preserve The Legacy Of Nancy Green, The Chicago Woman Who Played The Original 'Aunt Jemima'". WBEZ. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020.

- ^ Crowther, Linnea (June 19, 2020). "Finally, a proper headstone for the original Aunt Jemima spokeswoman, Nancy Green". legacy.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2020.

- ^ Gibson, Tammy (August 31, 2020). "Nancy Green, the Original face of Aunt Jemima, Receives a Headstone". The Chicago Defender. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Erick (September 15, 2020). "Nearly 100 years later, original Aunt Jemima gets a headstone". The Chicago Crusader. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020.

- ^ "'Aunt Jemima' Back: Famous Baker of Hoe Cakes Returns from Her Service in Corn Kitchen of Paris Exposition". Independence Daily Reporter. Independence, Kansas. December 3, 1900. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Agnes Moody, 'Aunt Jemima' actress, dies in Chicago". The Pittsburgh Gazette. April 10, 1903. p. 2.

- ^ a b Hollister, Stacy (October 2002). "Texas History 101: The northeast town of Hawkins remembers one of its small-town girls". Texas Monthly. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020.

- ^ Popik, Barry (December 8, 2006). "Pancake Capital of Texas". Archived from the original on September 27, 2020.

- ^ "State Planning to Honor 'Aunt Jemima,' Hawkins with Historical Marker". Longview News-Journal. June 29, 2012. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021.

- ^ "Details – Lillian Richard – Atlas Number 5507016717 – Atlas: Texas Historical Commission". atlas.thc.state.tx.us. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Mandy Lou Takes Spot From Stars". The Pittsburgh Press. May 14, 1933. Retrieved July 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Hansen, John Mark (June 19, 2020). "The real stories of the Chicago women who portrayed Aunt Jemima". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020.

- ^ "Aunt Jemima: Our History". Quaker Oats. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c Tucker, T. J. (January 16, 2001). "Rosa Washington Riles – Aunt Jemima born in Brown County". Ledger Independent. Maysville, Kentucky.

- ^ Berry, Karin D. (September 2, 1991). "Aunt Jemima Tribute Falls Flat as Pancake". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ Albrecht, Brian E. (May 4, 2001). "Ohioans proud to honor one of own, 'Aunt Jemima'". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ a b Sloan, Bob (May 7, 2009). "Book details history of Wallace's own 'Aunt Jemima'". The Cheraw Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Case, Dick (November 3, 2002). "Book serves up the life of Syracuse's 'Aunt Jemima'". The Post-Standard. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Wight, Conor (June 17, 2020). "The Syracuse resident that portrayed Aunt Jemima, and the racist history of the character". CNYCentral.com. Sinclair Broadcast Group. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Croyle, Johnathan (June 18, 2020). "Exploring Syracuse's tie to the controversial 'Aunt Jemima' brand". syracuse.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Edith Wilson, Actress and Jazz Vocalist, 84". The New York Times. Associated Press. April 1, 1981. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021.

Miss Wilson, who portrayed Aunt Jemima for the Quaker Oats Company for 18 years ...

- ^ "Miss Ethel Harper Assumes Duties of President of City Federation". The Birmingham Reporter. October 1, 1932. p. 5. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ethel 'Aunt Jemima' Harper Dies at 75". Jet. April 19, 1979. p. 60. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021.

- ^ Waligora-Davis, Nicole A. (2007). "Dunbar and the Science of Lynching". African American Review. 41 (2): 303–311. ISSN 1062-4783. JSTOR 40027064.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ "Betye Saar | American artist and educator". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021.

- ^ "Life Is a Collage for Artist Betye Saar". NPR.org. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021.

- ^ McElya, Micki (2007). Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02433-5. JSTOR j.ctvjf9z8t.

- ^ Rosen and Hughes (2019). "Aunt Jemima's Kitchen - 2019 - Question of the Month - Jim Crow Museum - Ferris State University". ferris.edu. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Passic, Frank (January 7, 2007). "The Key To The City". Morning Star. Historic Albion Michigan, Albion History/Genealogy Resources. p. 7. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ Lowe, Kelly (2007). The words and music of Frank Zappa. United Kingdom: Bison Books. p. 68. ISBN 9780803260054.

- ^ Morris, Bob (June 11, 2020). "Faith Ringgold Will Keep Fighting Back". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ "Burn Hollywood Burn". genius.com/. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. (lyrics of a song by the group Public Enemy)

- ^ Parker, Trey; Stone, Matt (September 24 – December 10, 2014). "Gluten Free Ebola". South Park: Season 18. South Park. Comedy Central.

- ^ Henderson, Cydney (November 8, 2020). "'SNL:' Dave Chappelle, Pete Davidson break character during Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben's firing". USA Today. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Judas and the Black Messiah [00:57:47]

Further reading

[edit]- Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (1962). Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. University of Michigan Press – Ann Arbor. ISBN 9780472116140.

- Marquette, Arthur F. (1967). Brands, Trademarks, and Good Will: The Story of the Quaker Oats Company. McGraw-Hill. ASIN B0006BOVBM.

- Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Stereotyping[permanent dead link], Kenneth Goings, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1994, ISBN 0-253-32592-7

- Manring, Maurice M. (1995). "Aunt Jemima Explained: The Old South, the Absent Mistress, and the Slave in a Box". Southern Cultures. 2 (1): 19–44. doi:10.1353/scu.1995.0059. JSTOR 26235388. S2CID 145517461.

- Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima, Maurice M. Manring, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1998, ISBN 0-8139-1811-1

- Black Hunger: Soul Food and America, Doris Witt, ebrary, Inc, University of Minnesota Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8166-4551-5, ISBN 978-0-8166-4551-0

External links

[edit]- Pearl Milling Company official website (2021–present)

- Aunt Jemima official website (2020) at the Wayback Machine (archived January 23, 2020)