This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

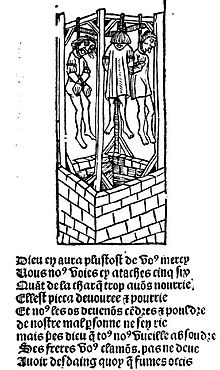

The Ballade des pendus, literally "ballad of the hanged", also known as Epitaphe Villon or Frères humains, is the best-known poem by François Villon. It is commonly acknowledged, although not clearly established, that Villon wrote it in prison while he awaited his execution. It was published posthumously in 1489 by Antoine Vérard.

Title

[edit]In the Coisline manuscript, this ballade has no title, and in the anthology Le Jardin de Plaisance et fleur de rethoricque printed in 1501 by Antoine Vérard, it is just called Autre ballade (literally, "Another ballad"). It is titled Épitaphe Villon in the Fauchet manuscript and in Pierre Levet's 1489 edition, and it is called Épitaphe dudit Villon in the Chansonnier de Rohan. In his 1533 commented edition, Clément Marot names it: Épitaphe en forme de ballade, que feit Villon pour luy & pour ses compaignons s'attendant à estre pendu avec eulx, which translates approximately to: Epitaph in the form of a ballad, which Villon made for him & for his companions expecting to be hanged with them. The modern title is due to the romantics and is problematic because it reveals the identity of the narrators too early and compromises the effect of surprise desired by Villon.

The title Epitaph Villon and its derivatives are also improper and confusing, because Villon had already written a real epitaph for himself at the end of Testament (around 1884 to 1906). Moreover, this title (and in particular the Marot's version) implies that Villon composed the work while awaiting his hanging, remains in question.

Villon's historians and commentators have now mostly resolved to designate this ballad by its first words: Frères humains (literally, "Human brothers"), as is customary when the author has assigned no title.

The title Ballade des pendus subsequently given to this ballad is all the less appropriate since there already exists a ballad with that title by Théodore de Banville, in his one-act play Gringoire (1866). This ballad has been renamed Le Verger du Roi Louis, but that is not the title given by the author either.

Context

[edit]It is often said that Villon composed this ballade while awaiting his execution following the Ferrebouc affair, in which a papal notary was injured in a brawl with Villon and his friends. In support of this point of view, Gert Pinkernell underlines the desperate and macabre nature of the text and concludes that Villon must have composed it in prison. However, as Claude Thiry notes: “It is a possibility, but among others: we cannot completely exclude it, but we should not impose it.” He remarks indeed that it is far from the only text of Villon which refers to his fear of the gallows and to the dangers which await lost children.[1] The Ballades en jargon, for example, contain many allusions to the gallows, but they were not necessarily composed during his imprisonment. Moreover, Thiry points out that, if we disregard the modern title, the poem is an appeal to Christian charity towards the poor more than towards the hanged, and, unlike the large majority of Villon's texts, the poet does not present this one as autobiographical. In addition, the macabre character of the ballad is not unique to it, as it is also found in the evocation of the mass grave of the innocents from stanzas CLV to CLXV of the Testament .

Background

[edit]This poem is an appeal to Christian charity, a highly respected value in the Middle Ages (as seen in the third and fourth lines of the first stanza: "For, if you take pity on us poor fellows, God will sooner have mercy on you."). Redemption is at the heart of the ballad. Villon recognizes that he has focussed too much care of his physical being to the detriment of his spirituality. This observation is reinforced by the very raw description of the rotting bodies (probably inspired by the macabre spectacle of the mass grave of the innocents) which contrasts with the religious themes of the poem.[1] The hanged first exhort passers-by to pray for them, then in the final stanza, the prayer is extended to all humans.

Form

[edit]The poem is in the form of a large ballade (3 dizains and 1 quintil, with decasyllabic verses)

- All lines have 10 syllables.

- The last line is the same in each stanza.

- The first three stanzas have 10 lines, and the last has 5 lines.

- Each stanza has the same rhyme scheme.

- There are several enjambments.

Text of the ballad with English translation

[edit]The translation deliberately follows the original as closely as possible.

Frères humains, qui après nous vivez, |

Human brothers who live after us, |

French Source:,[2] English source:[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "La ballade des pendus - Villon, Poésies diverses". www.bacdefrancais.net. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ "François Villon : La Ballade des pendus". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ Lagarde A & Michard L (1962). Moyen Age. France: Bordas. p. 219.

External links

[edit] (in French) Livres audio mp3 gratuits 'Ballade des pendus' de François Villon - (Association Audiocité).

(in French) Livres audio mp3 gratuits 'Ballade des pendus' de François Villon - (Association Audiocité).- Sung version of the poem performed by Serge Reggiani, composed by Louis Bessières (on YouTube).

- Sung version of the poem performed by Anika Kildegaard, composed by Jean-François Charles (on YouTube).