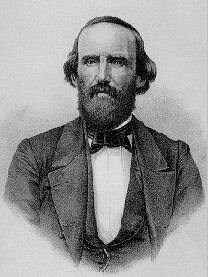

Benjamin McCulloch | |

|---|---|

Benjamin McCulloch | |

| Born | November 11, 1811 Rutherford County, Tennessee |

| Died | March 7, 1862 (aged 50) Benton County, Arkansas |

| Place of burial | State Cemetery in Austin, Texas |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1835–1836; 1840–1845 (Texas Army) 1846–1847 (Texas Militia) 1861–1862 (CSA) |

| Rank | First Lieutenant (Texas Army) Major General (Texas Militia) |

| Battles / wars | Texas Revolution Mexican–American War American Civil War |

Brigadier-General Benjamin McCulloch (November 11, 1811 – March 7, 1862) was a soldier in the Texas Revolution, a Texas Ranger, a major-general in the Texas militia and thereafter a major in the United States Army (United States Volunteers) during the Mexican–American War, sheriff of Sacramento County, a U.S. marshal, and a brigadier-general in the army of the Confederate States during the American Civil War. He owned at least 91 slaves.

McCulloch was killed during the Battle of Pea Ridge.

Early life

[edit]He was born November 11, 1811, in Rutherford County, Tennessee, one of twelve children and the fourth son of Alexander McCulloch and Frances Fisher LeNoir. Benjamin's father Alexander, a Yale University graduate, was a descendant of Captain Nicolas Martiau, the French Huguenot settler of Jamestown, Virginia and ancestor of President George Washington, and also had Scots-Irish ancestry. Alexander was also an officer on Brig. Gen. John Coffee's staff during the Creek War of 1813 and 1814 in Alabama (and apparently at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815). His mother was a daughter of a prominent Virginian planter. The McCulloch family had been wealthy, politically influential, and socially prominent in North Carolina before the American Revolution, but Alexander had wasted much of his inheritance and was unable even to educate his sons. (Two of Ben's older brothers had briefly attended a school in Tennessee taught by their neighbor, Sam Houston.) One of Ben's younger brothers was Henry Eustace McCulloch, also a Confederate general officer. Another brother, Alexander, served in the Texas Revolution and as a captain in Mexico.

The McCulloch family, like many on the frontier, moved often by choice or necessity. In the twenty years following their move from North Carolina and Ben's birth, they lived in eastern Tennessee, Alabama, and then western Tennessee. They finally settled at Dyersburg, where one of their closest neighbors was Davy Crockett, a great influence on young Ben.

In 1834, McCulloch headed west. He reached St. Louis just too late to join the fur trappers headed for the mountains for the season. He then tried to join a freight company heading for Santa Fe as a muleskinner, but was told they had a full complement. He moved on to Wisconsin to investigate lead-mining, but found all the best claims already staked by the large mining companies. In the fall of 1835, he returned to Tennessee to take up farming.

Texas career

[edit]When Crockett went to Texas in 1835 (following his defeat in his third congressional campaign), Ben McCulloch—tired of farming and seeking adventure—decided to accompany him, as did his brother Henry McCulloch. They planned to meet Crockett's Tennessee Boys at Nacogdoches on Christmas Day. Crockett's arrival in Nacogdoches was delayed due to hunting between the Bois d'Arc Creek and Choctaw Bayou. By January 5, 1836, Crockett found his way to Nacogdoches. There, Ben McCulloch greeted him after having convinced his brother, Henry McCulloch to return to Tennessee. Ben subsequently contracted measles and was bedridden for several weeks. Crockett pressed on toward San Antonio. McCulloch's illness prevented him from arriving in San Antonio until after the Alamo had already fallen.

McCulloch joined the Texas army under Sam Houston in its retreat to east Texas. Assigned to Captain Isaac N. Moreland's artillery company at the Battle of San Jacinto (April 21, 1836), he commanded one of the "Twin Sisters"—two six-pounder cannon sent to aid the Texans by the citizens of Cincinnati. One of the twin sisters was named Eleanor, the other Elizabeth. It is believed he chose to command Elizabeth to honor his dear friend and mentor, David Crockett, whose widow was Elizabeth Crockett. He made deadly use of his cannon against the Mexican positions and received a battlefield commission as first lieutenant. For his service (dating before April 18, 1836), McCulloch was issued Texas Bounty Certificate No. 2473 for 320 acres (.5 mi2, 1.3 km2). In 1839, he also received Donation Certificate No. 776 for 640 acres (1 mi2, 2.6 km2), for his service at San Jacinto.

McCulloch was then attached to Captain William H. Smith's cavalry company,[1] but returned to Tennessee to recruit a company of volunteers to return to Texas. He returned a few months later with a company of thirty volunteers which he had placed under the command of his friend, Robert Crockett, David Crockett's son.

By 1838, he had taken up the profession of surveying land for the Republic of Texas in and around the community of Seguin, later joining the Texas Rangers as lieutenant to Captain John Coffee "Jack" Hays. He acquired a reputation as an Indian fighter, favoring shotguns, pistols, and Bowie knives to the regulation saber and carbine.

On the strength of his new fame, he was elected to the Republic of Texas House of Representatives in 1839. The campaign was contentious, and McCulloch fought a rifle duel the next year against Colonel Reuben Ross, resulting in a wound that left his right arm crippled for life. Ben considered the matter closed, but it flared up again the following year, this time involving Henry McCulloch, who killed Ross with a pistol.

In 1842, McCulloch went back to surveying and intermittent military service. At the Battle of Plum Creek, August 12, 1840, he served as a scout against the Comanches, and then commanded the right wing of the Texas army. When a Mexican raiding party under General Ráfael Vásquez invaded San Antonio in February 1842, McCulloch was prominent in the fighting that pushed the Mexicans back beyond the Rio Grande. A second Mexican raid led by General Adrian Woll in September of that year again captured San Antonio. McCulloch then served as a scout for Captain Hays' Rangers. He and his brother, Henry, subsequently took part in the failed Somervell expedition and both escaped very shortly before most of the Texans were captured at Ciudad Mier, Mexico in Tamaulipas, December 25, 1842.

Samuel Reid, a volunteer from Louisiana, described McCulloch and his ranger company as "men in groups with long beards and mustaches, dressed in every variety of garment, with one exception, the slouched hat, the unmistakable uniform of a Texas ranger, and a brace of pistols around their waists, [who] were occupied drying their blankets, cleaning and fixing their guns, and some employed cooking at different fires, while others were grooming their horses. A rougher-looking set we never saw. They were without tents, and a miserable shed afforded them the only shelter. Captain McCulloch introduced us to his officers and many of his men, who appeared orderly and well-mannered people. But from their rough exterior, it was hard to tell who or what they were. Notwithstanding their ferocious and outlaw look, there were among them doctors and lawyers and many a college graduate."

War with Mexico

[edit]In 1845, McCulloch was elected from Gonzales County to the first Texas state legislature following its entry into the union. In the spring of 1846, a law was passed appointing him Major-General in command of all Texas militia west of the Colorado River. That same year, with the outbreak of the war with Mexico, he raised a company of Rangers that became Company A of Col. Hays's 1st Regiment of Texas Mounted Volunteers, who were known for their ability to regularly travel 250 miles in ten days or less. He subsequently was named chief of scouts under Gen. Zachary Taylor, with the rank of major, and became known nationwide for his daring exploits in northern Mexico. (His company of scouts included George Wilkins Kendall, editor of the New Orleans Picayune.) By this time, McCulloch was fluent in Spanish and his woodsman's skills enabled him to slip back and forth across the lines undetected—more than once penetrating to within a mile of Santa Anna's own tent.

McCulloch led his scouting company as mounted infantry at the Battle of Monterrey and his expert reconnaissance work preceding the Battle of Buena Vista probably saved Taylor's army from disaster.(how?) After Buena Vista he was promoted to the rank of major of U.S. Volunteers.

At the war's end, McCulloch scouted for Maj. Gen. David E. Twiggs, but joined the rush to the California gold fields in 1849. While he never struck gold, he was elected sheriff of Sacramento. (His old commander, Col. Hays, had been elected sheriff of San Francisco on the same day.) His old friends Sam Houston and Thomas J. Rusk, both now in the U.S. Senate, tried to arrange for his appointment to command a frontier army regiment, but his lack of formal education was against him and the appointment never went through. In 1852, President Franklin Pierce promised him command of the U.S. Second Cavalry, but Secretary of War Jefferson Davis gave it instead to Albert Sidney Johnston.

McCulloch was appointed U.S. marshal for the Eastern District of Texas in 1852, serving throughout the Pierce and Buchanan administrations. However, conscious of his lack of formal military education, he actually spent much of his term studying military science in libraries in Washington, D.C. In the aftermath of the Utah War, in 1858 he was one of two Peace Commissioners sent to deliver President Buchanan's pardon to Brigham Young in Utah (the other being former Gov. Lazarus W. Powell of Kentucky). As the Commissioners stated during meetings with Brigham and Church leadership, they had no power to negotiate. The Buchanan pardon was non-negotiable: 1) submit to Federal authority, and 2) allow the army to pass through Salt Lake City and establish a post somewhere in Utah. Brigham accepted the pardon under protest that the members of the Church had committed no crimes other than burning the US Army supply train contracted with Majors & Waddell, on the high plains of Wyoming. McCulloch in effect ended the Utah War when he changed the tone of the 2-day meeting on the 2nd morning, June 12, 1858, as reported by the New York Herald, 9 August 1858, 8/2-3: "But while a torrent of beastly and disgusting words were issuing from the throat of [Apostle Erastus] Snow, Commissioner McCulloch interrupted him with this remark: "....but I tell you sir, the army shall come in, and no power here can prevent it.""

Civil War service

[edit]Texas seceded from the union on February 1, 1861, and on February 14, McCulloch received a colonel's commission from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, with the comment that "to Texans, a moment's notice is sufficient when their State demands their service." He was authorized to demand the surrender of all federal military posts in the state. Subsequently, on the morning of February 16, U.S. Army General Twiggs, finding that more than 1,000 Texas troops had surrounded his installations in an orderly manner during the night, turned over to McCulloch all federal property in San Antonio. In return Twigg's troops were to be allowed to leave the state unharmed. On May 11, President Davis appointed McCulloch a brigadier-general.

McCulloch was placed in command of the Indian Territory. He set up his headquarters at Little Rock, and began piecing together an Army of the West, with regiments from Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana. He disagreed strongly with General Sterling Price of Missouri, but with the assistance of Brigadier-General Albert Pike, he was able to build alliances for the Confederacy with the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek nations.

On August 10, 1861, McCulloch's troops, though relatively poorly armed, handily defeated the army of Brigadier-General Nathaniel Lyon at the Battle of Wilson's Creek, Missouri. "We have an average of only twenty-five rounds of ammunition to the man," McCulloch reported, "and no more to be had short of Fort Smith and Baton Rouge." He did not have a high opinion of Price's Missourians, noting that they were undisciplined, commanded mostly by incompetent and inexperienced politicians, and possessed only a poor mix of weapons and equipment. For some 5,000 of them, their enlistment time was up and they were anxious to go home. Cooperation between the Arkansas and Missouri contingents was feeble, with "little cordiality of feeling between the two armies." His lack of confidence in the Missourians led McCulloch to hesitate when a bold attack might well have destroyed Lyon's smaller force and given Missouri to the Confederacy.

The continuing feud between McCulloch and Price led to the appointment of Major-General Earl Van Dorn to overall command, Henry Heth and Braxton Bragg having declined the appointment. When Van Dorn launched an expedition against St. Louis, a strategy McCulloch strongly opposed, it was again McCulloch's reconnaissance that contributed most to what little success Van Dorn's plan was able to achieve.

McCulloch commanded the Confederate right wing at the Battle of Pea Ridge (or Elkhorn Tavern), Arkansas, and on March 7, 1862, after much maneuvering his troops overran a key Union artillery battery. Union resistance stiffened late in the morning, however, and as McCulloch rode forward to scout out enemy positions, he was shot out of the saddle and died instantly. McCulloch always disliked army uniforms and was wearing a black velvet civilian suit and Wellington boots at the time of his death. Credit for the fatal shot was claimed by sharpshooter Peter Pelican of the 36th Illinois Infantry.

McCulloch's next in command, Brig. Gen. James M. McIntosh, head of the cavalry, was killed a few minutes later in a charge to recover McCulloch's body. Confederate Col. Louis Hébert was captured in the same charge, and the Confederate forces, with no remaining leadership, slowly fell apart and withdrew. Historians generally blame the Confederate disaster at Pea Ridge and the subsequent loss of undefended Arkansas on the death of McCulloch.

McCulloch's body was buried on the field at Pea Ridge, but was subsequently removed with other victims of the battle to a cemetery in Little Rock. He was later reinterred in the Texas State Cemetery in Austin; the gravesite is in the cemetery's Republic Hill section, Row N, No. 4. His papers are housed at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History (previously the Barker Texas History Center) at the University of Texas at Austin. McCulloch County, Texas, formed in 1856 and located in the present geographical center of the state, was named for him.[2] He is also one of thirty men inducted into the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame at Fort Fisher, Waco.

Shortly after Pea Ridge, Albert Pike, now a brigadier-general, constructed Fort McCulloch as the principal Confederate fortification in the southern section of the Indian Territory, naming it after his late commander. It was built on a bluff on the south bank of the Blue River and is now located in Bryan County, Oklahoma. It was placed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

Camp Ben McCulloch (see External Links below) was established near Austin in 1896 as a reunion site for the United Confederate Veterans and is the last such site still owned by the UCV's descendant group, the Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy. It is now a public recreation facility of some 200 acres (0.8 km2), operated by the County of Hays, and is a popular location for Central Texas family reunions, picnics, and musical festivals.

Several other members of McCulloch's family followed him to Texas, including his mother. She died in Ellis County in 1866 at the home of another of her sons, John C. McCulloch, who had been a captain in the Confederate army. Her remains were exhumed in 1938 by the State of Texas and reinterred beside those of Gen. Ben McCulloch, and a joint monument was erected. Other siblings lived in Gonzales and in Walker County.

In popular culture

[edit]- Steve Earle wrote a song about McCulloch on his album Train a Comin'. "Ben McCulloch" is sung from the perspective of a foot soldier in McCulloch's infantry, marched from Texas to fight in Missouri and growing to hate both McCulloch and the Civil War. Its chorus and refrain is "Goddamn you, Ben McCulloch / I hate you more than any other man alive // And when you die, you'll be a foot soldier just like me / in the Devil's infantry."

- He is the main antagonist in Harry Turtledove's short story "Lee at the Alamo" (2011). [1]

- He is also a character in Janice Woods Windle's True Women which was later made into a TV movie.

- There is a mention of McCulloch's Rangers in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian on page 95, where the men from the Glanton gang are said to be from McCulloch's Rangers: "(...) Tate from Kentucky who had fought with McCulloch's Rangers as had Tobin and others among them (...)".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This William H. Smith was captain of 2nd Regiment Texas Volunteers Cavalry Company J, part of Sam Houston's Army at the Battle of San Jacinto. 'San Jacinto Veterans Unit' Archived 2017-07-09 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 15, 2012. In 1837, he was a major in charge of a battalion of Texas Rangers. See entry on "Fort Fisher" in 'The Handbook of Texas Online' Retrieved May 15, 2012, which mentions Major Smith.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 193.

References

[edit]- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Wright, Marcus J., General officers of the Confederate Army: officers of the executive departments of the Confederate States, members of the Confederate Congress by states. New York: The Neale Publishing Company 1911. OCLC 795106013. Reprinted Mattituck, NY: J.M. Carroll, 1983. OCLC 10362155. ISBN 0-8488-0009-5. Reprinted Conway, AR: Oldbuck Press, 1993. OCLC 29443870.

Further reading

[edit]- Cutrer, Thomas W. Ben McCulloch and the Frontier Military Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Gunn, Jack W. "Ben McCulloch: A Big Captain." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 58 (July 1954).

- McCulloch, Benjamin, "Memoirs", Missouri Historical Review (1932): 354ff.

- Reid, Samuel C. The Scouting Expeditions of McCulloch's Texas Rangers. Philadelphia, 1847; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1970 (reprint).

- Rose, Victor Marion. The Life and Services of Gen. Ben McCulloch. Philadelphia, 1888; Austin: Steck, 1958 (reprint).

- Undated clipping, probably from Dallas Herald, provided by Thomas R. Lindley; Henry McCulloch to Henry McArdle, January 14, 1891, Henry McArdle San Jacinto Notebook, TXSL.

- Earle, Steve. "Ben McCulloch". A song written from the perspective of a foot soldier in the Texas Infantry.

External links

[edit]- McCulloch Family Tree - Ben McCulloch Archived 2022-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Account of Ben McCulloch's Peach Creek fight in 1839 from Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas by John Henry Brown, published 1880, hosted by The Portal to Texas History

- Benjamin McCulloch from the Handbook of Texas Online

- A Guide to the Ben and Henry Eustace McCulloch Family Papers, 1798-1961, Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

- murfreesboropost.com Murfreesboro Post site biography of McCulloch.

- nps.gov National Park Service site biography of McCulloch.

- [2] Camp Ben McCulloch, Hays County, Driftwood TX

- [3] Camp Ben McCulloch (map), Hays County TX, Google Maps