Title page of volume I | |

| Author | John Neal |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

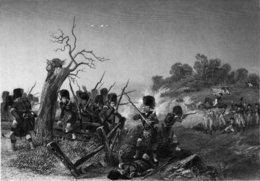

| Set in | American Revolutionary War |

| Publisher | William Blackwood |

Publication date | 1825 |

| Publication place | UK |

| Pages | 1,324 |

| OCLC | 3593743 |

Brother Jonathan: or, the New Englanders is an 1825 historical novel by American writer John Neal. The title refers to Brother Jonathan, a popular personification of New England and the broader United States. The story follows protagonist Walter Harwood as he and the nation around him both come of age through the American Revolution. The novel explores cross-cultural relationships and highlights cultural diversity within the Thirteen Colonies, stressing egalitarianism and challenging the conception of a unified American nation. It features mixed-race Anglo-Indigenous characters and depicts them as the inheritors of North America. The book's sexual themes drew negative reactions from contemporary critics. These themes were explicit for the period, addressing female sexual virtue and male guilt for sexual misdeeds.

Literature scholars have praised Brother Jonathan's extensive and early use of realism in depicting American culture and speech. Using phonetic transcriptions, the dialogue documents a wide range of regional accents and colloquialisms. Included in the dialogue is a likely-accurate depiction of American Indian English, and what may be American literature's earliest attempt to express a wide range of emotion using children's natural speech patterns. Neal's characterizations of American character and speech were praised in the UK but derided in the US. The author nevertheless considered them central to developing an American literature distinct from British precedent.

Neal wrote the original manuscript while crossing the Atlantic from Baltimore in early 1824, then revised it in London many times before convincing William Blackwood of Edinburgh to publish it in mid-1825. It is Neal's longest work and possibly the longest single work of American fiction until well into the twentieth century. The editing process was the most laborious of Neal's career and resulted in a number of inconsistencies in the plot. The author fashioned many of the deleted sections into separate works he published later. Considered one of America's top novelists at the time, Neal wrote Brother Jonathan with a British audience in mind in order to boost his reputation internationally. It was a financial failure that received mixed but mostly warm reviews at the time. Twenty-first century readers are generally unaware of the book, and many scholars consider it too complex to be considered good.

Plot

[edit]The storyline begins in 1774 in the Connecticut home of Presbyterian preacher Abraham Harwood. Abraham lives in the fictional community of Gingertown with his son Walter Harwood, his Virginian niece Edith Cummin, and a mysterious figure named Jonathan Peters. The introductory chapters illustrate the individual nature of the characters within the specific cultural context of New England. Walter loves Edith and feels jealous of her relationship with Jonathan. Abraham becomes implicated in a murder that occurred near Abraham's church, but the community turns its attention to Jonathan and drives him out of Gingertown.

Walter becomes restless in his rural surroundings, but his father will not let him leave for New York City. Walter grew up spending time in the forest among Indigenous people, particularly his friend Bald Eagle. When Walter gets caught in a spring flood, Bald Eagle saves him and brings him home. Edith and Walter express love for each other and become engaged.

With his father's consent, Walter takes a stage coach to New York following a send-off from community members exhibiting New England customs. He gets a job in a counting house and moves into a Quaker household, where he learns that his father has been killed and his family home seized by British Loyalists.

Walter meets a young man named Harry Flemming who has news concerning Edith. He reports that she is living among high society in Philadelphia and has asked for news of Jonathan. This inquiry reignites Walter's jealousy. Walter ends the engagement and develops relationships with two other women: Mrs. P. and Olive Montgomery. Olive knows Edith from childhood and met Jonathan through Harry.

Walter and Harry get very drunk while observing riotous behavior during Declaration of Independence celebrations. Harry leads Walter to the luxurious home of a courtesan named Emma. She seduces Walter and they sleep together, though he is troubled by thoughts of Edith.

Walter finds a note written by Abraham explaining that Walter's father is not Abraham but, rather, a man named Warwick Savage, whom Abraham murdered upon discovering Warwick's sexual affair with his wife. The note also explains how Jonathan was implicated by his appearance near the murder scene. It also describes the strange likeness between Jonathan and Warwick.

Walter joins the Continental Army and serves under Captain Nathan Hale and Colonel Warwick Savage. Walter is bothered by the colonel's resemblance to Jonathan, then learns from Indigenous friends and from a letter from Edith that Warwick is actually Jonathan using a false identity. Walter learns that Jonathan has sinister reasons for joining the army. Jonathan tries to kill Walter during the Battle of Long Island and Walter wounds him in self defense.

Walter is severely wounded during the Battle of Harlem Heights and he returns to his Quaker hosts. He is nursed by the daughter in the household, Ruth Ashley, who has held unrequited romantic feelings for him since he arrived in New York a year earlier. Meanwhile, Walter is haunted by dreams of Jonathan Peters. Walter recovers and hears that Olive is dying, so he ventures to visit her in an Indigenous settlement outside the city. Along the way, he witnesses Nathan Hale's execution and is nearly executed himself. Bald Eagle liberates Walter from enchantment by an Indigenous witch named Hannah, which had been causing his dreams of Jonathan and related suicidal thoughts. Upon meeting with Olive, Walter learns that her love for him is causing her death. She makes a contradictory statement regarding whether Walter should marry Edith, then dies.

Edith tells Walter that the real Warwick had a brother who is using Warwick's name to escape punishment for committing crimes. It becomes unclear whether Abraham's murder victim was Warwick or the brother. Walter visits Edith where she is staying with Benedict Arnold. He witnesses her in a possibly romantic exchange with Jonathan and leaves without seeking an explanation from either. He rushes to Emma's home, seduces her, sleeps with her, and proposes marriage. Opposed to the institution of marriage, Emma refuses, but offers him advice. Walter sees her as a more upstanding character than before.

Walter learns that Jonathan and Benedict Arnold are collaborating as traitors. Harry pursues them and wounds Jonathan. Emma gives birth to Walter's child. Walter considers marrying Emma until the child dies. Emma advises Walter to return to Edith and he leaves Emma with a letter to deliver to Edith if he should die.

Edith tells Walter more about Warwick and his brother. She tells him to attend a meeting of Indigenous Penobscot leaders to learn more. Walter travels to the Massachusetts District of Maine and sees the results of the Burning of Falmouth. At Indian Island he learns of his distant Penobscot and Mohawk ancestry and meets up with Edith. He finds Warwick/Jonathan, whose real name is Robert Evans. Robert is his real father but thought Walter was Abraham's son and that Walter was responsible for the accidental infant death of Robert's other son. Robert's twin brother George Evans was the man murdered by Abraham. Harry is Walter's cousin, the illegitimate son of Abraham's sister and George. The novel closes: "Walter and Edith were happy: and Warwick Savage – alias, Jonathan Peters – alias, Robert Evans – he, though not happy, was no longer bad, or foolish."[1]

Background

[edit]At more than 1,300 pages across three volumes, Brother Jonathan is John Neal's longest book.[2] Writing in 1958, scholar Lillie Deming Loshe considered it the longest work of early American fiction and possibly longer than any other since.[3] There were no other works of American fiction comparable in scope, length, and complexity until the Littlepage Manuscripts trilogy (1845–1846) by James Fenimore Cooper.[4] Neal published it anonymously,[5] but revealed himself as the author through coded references in his 1830 novel, Authorship.[6]

In Baltimore in 1818, Neal collaborated with fellow Delphian Club cofounder Tobias Watkins to write A History of the American Revolution (published 1819) based on primary sources collected by another Delphian, Paul Allen.[7] In late November 1823, he was at a dinner party with an English friend who quoted Sydney Smith's then-notorious 1820 remark, "in the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?".[8] On December 15, 1823, he left Baltimore on a UK-bound ship.[9] Partly in response to Smith,[10] and drawing on that Revolutionary War research,[11] Neal wrote the first draft of Brother Jonathan while sailing across the Atlantic.[12] The working title was The Yankee,[13] and he intended it to be a major work[14] that would expand his recognition as a significant novelist beyond the US and into the UK.[15] Seventy-Six (1823) had gained him recognition as Cooper's chief rival as America's top novelist.[16] He hoped this new novel would boost his reputation to surpass Cooper's.[17]

Unlike his previous novels, Neal wrote Brother Jonathan with a British audience in mind.[18] His intention was to make the US, its language, and its customs more broadly recognized in the UK.[19] Soon after arriving in London in February 1824, he brought his manuscript to publishers in that city, but failed to convince any of them to publish it.[20] He approached the publishing company that pirated Seventy-Six and Logan, offering them his other Baltimore-published novels Errata and Randolph, but they refused to publish either.[21] His financial situation was becoming desperate[22] when, in April, William Blackwood of Edinburgh asked Neal to become a regular contributor to Blackwood's Magazine.[23] For the next year and a half, Neal was one of the magazine's most prolific contributors.[24]

While working on the American Writers series and other articles for Blackwood's, Neal rewrote Brother Jonathan with Blackwood in mind as a potential publisher.[25] He sent the manuscript to Edinburgh in October 1824.[26] Blackwood refused to publish, partly on account of the novel's sexual content, saying: "it is not fit for young people to read of seduction, brothels, and the abandonment of the sexes."[27] Based on feedback from both Blackwood and his associate David Macbeth Moir, Neal revised the novel and submitted a second draft in March 1825. Blackwood agreed to publish, but requested one more round of revisions, to which Neal agreed.[26] This process of revision was more laborious than for any other novel Neal published[28] and scholars blame it for many of the plot's inconsistencies.[29] Neal later used sections cut during those revision processes to create other works, including the essay "The Character of the Real Yankees" (The New Monthly Magazine 1826),[30] the fiction series "Sketches from Life" (The Yankee 1828–1829),[31] the fictional fragment "Males and Females" (The Yankee April 9, 1829),[32] the short story "Otter-Bag, the Oneida Chief" (The Token 1829),[33] and the novella Ruth Elder (Brother Jonathan magazine 1843).[34]

Blackwood published Brother Jonathan in early July 1825[35] and had 2,000 copies[2] printed by A. and R. Spottiswoode in London.[36] Blackwood paid Neal 200 guineas with the promise to pay 100 more after he sold the first 1,000 copies. Fewer than 500 copies sold before Blackwood deemed the venture a failure and his relationship with Neal broke down the following winter.[37] Neal agreed it was a failure,[27] but claimed it would have been a success had Blackwood allowed him to publish a story closer to the original manuscript.[38] Neal claimed that Cooper's publisher, Charles Wiley, agreed to publish Brother Jonathan in the US but never followed through. No records from Wiley exist to confirm.[39] As late as autumn 1828 and back in his home state of Maine, Neal continued pressuring Blackwood for the additional 100-guinea payment to no avail. Blackwood maintained that fewer than 500 copies had sold by that point.[40]

Themes

[edit]

Depicting Americans

[edit]Neal dedicated a large proportion of Brother Jonathan to the documentation of the peculiarities of the American people, particularly New Englanders.[41] American studies scholar Winifred Morgan claimed that no other author before him had attempted to craft such a vivid and extensive portrayal in literature.[42] As with much of his other literary work, Neal pursued the American literary nationalist goal of increasing cultural recognition of the US within the anglophone world.[43] To that end, he dedicated a great deal of space to scenes of distinctive American cultural events, customs, accents, colloquialisms, dress, cuisine, and characters.[44] The novel nevertheless presented readers with conflicting ideas about what it means to be an American and a New Englander.[45] The result, according to Morgan, is "the absolute impossibility of knowing anything for certain".[46]

The novel's title refers to the national emblem, Brother Jonathan, exemplified by the novel's protagonist, Walter Harwood.[47] Neal chose the name because it was used by his British contemporaries as a derogatory term for Americans, particularly those from his native New England region.[2] The emblem had been developing for decades as a minor self-referential device in American literature, but saw full development in this novel into the personification of American national character.[48] Though Brother Jonathan was initially considered to personify just the New England states, Neal advocated for Americans to accept him as a representation for the entire country.[49] Uncle Sam replaced Brother Jonathan in this regard later in the nineteenth century.[2]

National coming of age

[edit]Among other things, Brother Jonathan is a coming-of-age story about both the protagonist growing into manhood and about the new American nation as it is born in the American Revolution.[50] For Walter, this is exemplified by his transition from a rural upbringing in Connecticut to urban life in New York City.[51] Once in New York, Walter observes with disgust as wealthy city dwellers at his boarding house clean themselves with a common towel and toothbrush, comb their hair with their fingers, and arrange their collars and cravats to hide wear marks and stains. Yet, he is left feeling shame over his own unsophisticated country appearance.[52] On the one hand, exposure in New York to urban sophistication, love interests, and war corrupts his natural naivety.[53] On the other, Neal exalts Walter's provinciality in contrast to the elites, showing him better suited for self-governance.[54]

Neal used Walter to stand in for the American people as a naturally republican society oppressed by outside British control.[55] According to cultural studies researcher Jörg Thomas Richter, the stage coach that transported Walter to New York also exemplifies this natural American republicanism, as it depicts a curious mix of animals, cargo, and passengers of varying social status, all traveling together. He also argues that the character on the stage coach smoking a pipe dangerously close to a keg of gunpowder suggests that heterogeneous egalitarianism might have explosive consequences for the nation.[56] Pointing to other negative consequences of this egalitarianism, Neal depicts a vulgar display from New Yorkers in a Declaration of Independence celebration and poor discipline among Continental troops.[55]

Cultural diversity

[edit]Neal's earlier novel Seventy-Six depicts the Revolutionary War as a moment of national unification, but Brother Jonathan explores the same event as a portrait of the nation's complex cultural diversity. One example is how each novel's protagonist views his father. The father figure in Seventy-Six is a hero, whereas in Brother Jonathan he may be one of two different men, both of whom demonstrate significant character flaws.[57] To illustrate cultural diversity in the Thirteen Colonies, Brother Jonathan features colloquialisms and accents specific to Black Americans, American Indians, Southerners, New Englanders, and others.[58] Neal likely meant this as a challenge to the concept of the United States as a unified nation[59] and to stress the ideal of egalitarianism.[60]

The novel also explores relationships between culturally different characters and features a mixed-race protagonist.[61] The darker side of these cross-cultural interactions is exemplified by the graveyard in Gingertown as a haunting Gothic symbol for "the legacy of the American colonial project ... fertilized and poisoned with the blood of conquered and the conqueror alike", according to literature scholar Matthew Wynn Sivils.[62] However, unlike the mass death scene at the end of Neal's earlier novel Logan, which killed off every major character, Brother Jonathan's ending kills off two Indigenous characters and leaves the two mixed-race characters alive. Historian Matthew Pethers interprets this as Neal's take on the vanishing Indian: the common literary trope that depicts American Indians as a people vanishing to make way for Anglo-Americans as inheritors of the American landscape. In this version, the inheritors are a mixed-race people of both English and Indigenous descent.[61]

Sex

[edit]As with nearly all of Neal's novels,[63] Brother Jonathan includes scenes much more sexually explicit than its contemporaries.[10] Walter seduces Emma, and like in many of Neal's earlier novels, the male protagonist demonstrates guilt after committing sexual misdeeds. The story explores the consequences of those actions for both men and women.[64] Walter also grows in his views on female sexual virtue after becoming more acquainted with women of varying sexual activity in New York. He comes to dismiss virtuous women and praise the promiscuous as those who "fall, not because of their being worse – but because of their being better, than usual".[65] Publisher William Blackwood warned that "the pictures you give of seduction &c. are such as would make your work a sealed book to nine tenths of ordinary readers".[66] Scholar Fritz Fleischmann acknowledged the historic importance of the novel's treatment of female virtue, male profligacy, and seduction of women by men, but asserted that Neal failed to craft a successful theme on the topic.[67]

Style

[edit]Most of Neal's novels experimented with American dialects and colloquialisms,[68] but Brother Jonathan is considered by many scholars to be Neal's best and most extensive attempt in this regard.[69] Walter's dialogue in the first volume may be the earliest attempt in American literature to use a child's natural speech patterns to express a wide range of emotion. The novel's portrayal of Walter's transition to more adult language is described by scholar Harold C. Martin as "the oddest transformation ... in all of American literature".[70] The book's dialogue features phonetic transcriptions of speech patterns particular to New Englanders, Appalachian Virginians, rural Americans from the Mid-Atlantic, Indigenous Penobscot, Georgians, Scots, and enslaved Black Americans.[71] Literature scholar and biographer Benjamin Lease found the representation of American Indian English to be likely very accurate,[72] and Martin posited it was likely closer to reality than the work of contemporary novelists like James Fenimore Cooper.[73] Examples of Virginia colloquialisms in the novel include "I reckon", "jest", "mighty bad", and "leave me be".[65] The book's use of English is cited in the definitions of multiple words by the compilers of the Dictionary of American English,[74] The Oxford English Dictionary,[75] and A Dictionary of Americanisms.[76]

In the "Unpublished Preface" to Rachel Dyer (1828), Neal himself claimed the representation of American speech in Brother Jonathan as central to American literary nationalism – a movement that sought to develop an American literature distinct from British precedent.[19] In the novel itself, Neal used dialogue by the character Edith Cummin to express the predominant literary sentiment he opposed: "We all say that which none of us would write".[65] Lease felt his intention was successful: "Neal's adventurous experiments contributed significantly to our colloquial tradition."[77] Those experiments stood at the time in stark and controversial contrast to the broadly accepted literary standard of classical English and to efforts by contemporaries like Noah Webster to downplay regional variation in American English.[78]

"...modest women, hey? – no, no, Harry – that's goin' a little too fur. As for their – vir – vir – vir – why – hiccup – why; that's neither here, nor there – nobody can tell; but – a – a – as for their modesty – o – o – o, for shame – so – so – hiccup – so languishing; so prodigal of exposure – so – so – so full of treachery; a – a – hiccup – the – their mischievous – a – a blandishment – a – a – no, no, Harry."

Brother Jonathan introduced technical devices for conveying natural speech diction that no author used before Neal and that were not copied by his successors. Martin described it as a "rudimentary ... choppy style, aided by eccentric punctuation".[73] The novel's prolific use of italics and diacritics convey the stresses and rhythm of natural speech and peculiarities of regional accents.[80] The speech of a Connecticut farmer is thus captured for the reader: "In făct – I thoŭght – mȳ tĭme – hăd cŏme – sŭre enŏugh – I guĕss."[81] In many cases, dialogue between multiple characters runs together in a single paragraph to convey passion.[82] This experiment came after Neal played with omitting identifying dialogue tags in Seventy-Six (1823) and before he began omitting quotation marks in Rachel Dyer (1828).[77] Literature scholar Maya Merlob described the novel's less-intelligible examples as "ludicrous dialogue" that Neal concocted to subvert British literary norms and prototype a new literature as distinctly American.[83] Neal may also have been mimicking common speech patterns in order to make his novel appealing to a broader, and less educated, audience.[84]

Contemporary critique

[edit]

Critical reception of Brother Jonathan was mixed[85] but mostly warm.[86] Most of the positive criticism was qualified by commentary on the novel's shortcomings, such as what The Ladies' Monthly Museum published: "the striking delineations of New England manners are interesting as well as amusing, notwithstanding their coarseness."[87] Of Neal's previous novels, only Logan and Seventy-Six had been published in the UK. Compared to those, Brother Jonathan received more attention from British critics.[88] The Literary Chronicle and Weekly Review praised the earlier two novels, for instance, but was much more enthusiastic about Brother Jonathan.[87] Almost all critics found the novel puzzling.[89] American critics largely ignored the novel,[39] as did readers in both the US and UK.[90]

Depiction of Americans

[edit]Among American readers and critics who were aware of Brother Jonathan, most were angered by its caricatures of American speech and customs.[91] Returning to his native Portland, Maine, two years after publishing the novel, Neal found former friends refusing to meet with him.[92] He received threats, found printed denunciations posted throughout town, and got heckled in the street.[93] The formerly friendly journalist Joseph T. Buckingham of The New-England Galaxy in nearby Boston lambasted the novel's "gross and vulgar caricatures of New-England customs and language".[94] In contrast, Sumner Lincoln Fairfield of the New York Literary Gazette praised the novel as a "great success", particularly in its characterization of Americans.[95]

In stark contrast to the Americans, British critics praised Brother Jonathan's realistic depiction of American language and habits as its chief achievement.[96] The Literary Gazette praised it as "what an American novel should be: American in its scenes, actors, and plot".[97] Dumfries Monthly Magazine said "'Brother Jonathan' is the first publication of the kind that introduces us to anything like an accurate ... acquaintance with the inhabitants of the great continent – aborigines as well as colonists."[98] In a mostly negative review, the British Critic instructed readers to "skip or skim" most of the novel to get to "the vivid and eccentric pictures of American life and character with which it abounds."[99] On the other hand, John Bowring claimed that Jeremy Bentham assailed the novel as "the most execrable stuff that ever fell from mortal pen." Neal, who served as Bentham's secretary for more than a year following the novel's release, claimed Bowring libelously manufactured this quote.[100]

Sexual content

[edit]Many reviewers decried the novel's sexual content as offensive.[65] The British Critic summarized the novel's contents as "the adventures of profligates, misanthropes, maniacs, liars, and louts".[101] David Macbeth Moir claimed Neal demonstrated "a deficiency of just taste in what is proper for the public palate" and declared the novel "unfit for a circle of female readers". He continued: "Need I allude to such things as elaborate plans for female seduction, or pictures of male profligacy which startle while they astonish, and nauseate while they create interest."[102]

Excessive but powerful

[edit]Many critics complained that the story was hard to follow.[89] The New Monthly Magazine in London felt that Brother Jonathan was less excessive than Logan or Seventy-Six, but still disappointingly unrestrained.[103] The British Monthly Review called it a failure, saying "the general character of the style is that of exaggeration".[104] One reviewer for the British Critic described the novel's characters as exaggerated, referring to them as "stalking moody spectres with glaring eyeballs and inflated nostrils, towering above the common height, and exhibiting the play of their muscles and veins through their clothes in the most trivial action".[105] William Hazlitt of the Edinburgh Review felt that the novel tried too hard to amplify mundane aspects of American life: "In the absence of subjects of real interest, men make themselves an interest out of nothing, and magnify mole-hills into mountains."[106] The French Revue encyclopédique praised the narration and dialogue as poetic and eloquent, but also scattered and impossible to understand.[107] Moir predicted commercial failure for the book on the grounds that readers had no patience for such a demanding work, saying that Neal is "too fond of making a great deal of every thing".[102] Neal himself admitted to the novel's excesses, blaming them on his quest for originality: "I, wishing to avoid what is common, am apt to run off into what is not only uncommon, but unnatural, and even absurd."[65]

Despite criticizing the novel's exaggerated style, The New Monthly Magazine admitted it "display[ed] throughout the marks of great intellectual power."[103] The Edinburgh Literary Journal called it "full of vigour and originality".[108] The Literary Gazette claimed "it is a work no one could read through without acknowledging the author's powers."[97] When reviewing a Cooper novel in 1827, the same magazine claimed Logan, Seventy-Six, and Brother Jonathan to be "full of faults, but still full of power" and successful at positioning the author as Cooper's chief competitor.[109] Moir also offered praise: "It is extremely powerful – and, what is more to the purpose, its power is of a kind that is unhackneyed and original."[102] The Literary Chronicle and Weekly Review asserted "there are few novels – few indeed, which display so much talent or possess such a fearful interest as Brother Jonathan.[88] Commenting on both the novel's power and excesses, Peter George Patmore supposed that if Brother Jonathan was the anonymous author's first work, it was "destined to occupy a permanent place in the very foremost rank of his age's literature. .... But if its author has written two or three such works, we almost despair of his ever writing a better."[110]

Modern views

[edit]Twenty-first-century readers are generally unaware of Brother Jonathan.[111] Among scholars familiar with the work, many consider it bad or a failure.[112]

Realism

[edit]Scholars who have praised Brother Jonathan often focus on the realism achieved in the novel's depiction of American characters and scenes.[113] Fleischmann felt it was the novel's greatest achievement.[114] Lease and fellow literature scholars Hans-Joachim Lang and Arthur Hobson Quinn claimed that this level of realism was uniquely high for the early nineteenth century.[115] Lease and Lang claimed that "to find a counterpart of the power and subtlety ... it is necessary to turn to the best of Hawthorne and Melville."[116] Biographer Irving T. Richards called it "flat, crass realism, of an excellent sort".[117] Authors of the Literary History of the United States praised the "extraordinary fidelity" of the depiction of American speech.[118]

Complexity

[edit]Many scholars have judged the novel's plot to be overly complex.[119] Richards referred to it as "a most inharmonious whole"[120] and Fleischmann called it "an ill-designed shambles".[121] The plot was "brilliant yet exasperating" according to biographer Donald A. Sears,[2] while Morgan called it "overstuffed".[122] Sivils called Brother Jonathan a "hodgepodge of a novel" that attempted to combine too many different genres and to document too much about American life.[123]

Richards and Richter both complained of an incongruous mixture of realism and fantastical Gothic devices,[124] which Lease and Lang referred to as "vast quantities of Gothic mystification".[116] Richter and Sears both felt that the narrative shifted abruptly between following Walter Harwood and Jonathan Peters.[125] Fleischmann and Lease contended that Walter's sudden transformation "from a virtuous lad of countrified looks to an elegant profligate"[27] is unwarranted.[126] Fleischmann went on to argue that Walter's jealousy is too intense given the limited interactions between Edith and Jonathan.[127] Martin argued that the plot's excesses and inconsistencies were accentuated by Neal's experiments in diction and syntax.[128] Referring to this mix of style experiments, American realism, Gothic devices, and an excessive plot, scholar Alexander Cowie summarized: "To see unity in the vast conglomeration of Brother Jonathan is impossible."[89]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Neal 1825, p. 452 (volume III).

- ^ a b c d e Sears 1978, p. 73.

- ^ Loshe 1958, p. 93.

- ^ Sivils 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 661.

- ^ Welch 2021, p. 494n11.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 40.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 70; Lease 1972, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Daggett 1920, p. 9.

- ^ a b Sears 1978, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 1003.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 468.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 44.

- ^ Martin 1959, p. 466.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 72.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 39.

- ^ Gura 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Richter 2018, pp. 255–256, 260n7; Quinn 1964, p. 49.

- ^ a b Richards 1933, pp. 694–695.

- ^ Sears 1978, pp. 70–71; Richards 1933, p. 658.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 470.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 71.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 49.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 50; Sears 1978, p. 71.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 658.

- ^ a b Lease 1972, pp. 55–58.

- ^ a b c Fleischmann 1983, p. 287.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 661–662.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, pp. 287–289.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 528–529; Lease 1972, p. 110n2.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 619.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 618–619.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 293; Sears 1978, p. 73.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 1059n1.

- ^ Lease & Lang 1978, p. x.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 660.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 73; Lease 1972, p. 59; Richards 1933, p. 497.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Lease 1972, p. 64.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 500–502.

- ^ Sears 1978, pp. 74–75; Cowie 1948, p. 172.

- ^ Morgan 1988, p. 156.

- ^ Sivils 2012, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Orestano 1989, p. 138; Quinn 1964, p. 49; Cowie 1948, p. 172; Sears 1978, pp. 74–75; Lease 1972, p. 153; Pethers 2012, p. 23; Richter 2018, p. 251.

- ^ Schäfer 2016, p. 233.

- ^ Morgan 1988, p. 153.

- ^ Richter 2018, p. 250; Morgan 1988, p. 155; Kayorie 2019, p. 88.

- ^ Morgan 1988, p. 143; Kayorie 2019, p. 88.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 1031.

- ^ Morgan 1988, p. 155; Schäfer 2021.

- ^ Kayorie 2019, p. 88; Fleischmann 1983, p. 361n214; Richter 2018, p. 250.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 112.

- ^ Kayorie 2019, p. 88; Richter 2018, pp. 251–254.

- ^ Schäfer 2016, p. 241.

- ^ a b Fleischmann 1983, p. 317.

- ^ Richter 2018, p. 250.

- ^ Pethers 2012, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Schumacher 2018, p. 156.

- ^ Richter 2018, p. 259; Pethers 2012, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Richter 2018, p. 258.

- ^ a b Pethers 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Sivils 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 246.

- ^ Lease & Lang 1978, p. xvii; Fleischmann 1983, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d e Sears 1978, p. 75.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 56.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, pp. 288–291.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 116; Sears 1978, p. 75; Kayorie 2019, p. 89; Martin 1959, p. 468.

- ^ Martin 1959, p. 469.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 116; Kayorie 2019, p. 89; Martin 1959, p. 468; Pethers 2012, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 116.

- ^ a b Martin 1959, p. 468.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 189.

- ^ Murray, James A. H., ed. (1978). The Oxford English Dictionary Being a Corrected Re-Issue with an Introduction, Supplement, and Bibliography of A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles Found Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. Vol. XII. Oxford, UK: The Clarendon Press. pp. 14, 15. OCLC 33186370.

- ^ Mathews, Mitford M., ed. (1966). A Dictionary of Americanisms on Historical Principles. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 13, 20, 163, 1, 896. OCLC 319585.

- ^ a b Lease 1972, p. 117.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 37n105.

- ^ Neal 1825, pp. 403–404 (volume II).

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 75; Cowie 1948, p. 172; Pethers 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Martin 1959, p. 471.

- ^ Merlob 2012, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Merlob 2012, p. 109.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 59; Lease & Lang 1978, p. x.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 662.

- ^ a b Richards 1933, p. 663.

- ^ a b Cairns 1922, p. 210.

- ^ a b c Cowie 1948, p. 172.

- ^ Sears 1978, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 675–676; Fleischmann 1983, p. 150.

- ^ Todd 1906, p. 66.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 150.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 123; Lease & Lang 1978, p. xv; Richards 1933, p. 675.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 570.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 675–676.

- ^ a b Cairns 1922, p. 34.

- ^ Cairns 1922, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 665–666.

- ^ King 1966, p. 50.

- ^ Lease & Lang 1978, p. x; Cowie 1948, p. 273; Cairns 1922, pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b c Richards 1933, p. Appendix A.

- ^ a b Richards 1933, p. 664.

- ^ Cairns 1922, p. 211.

- ^ Cairns 1922, p. 212.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 690.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 59.

- ^ Cairns 1922, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 673–674.

- ^ Richter 2018, p. 251.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 693; Sivils 2012, p. 46; Sears 1978, p. 76; Morgan 1988, p. 156.

- ^ Quinn 1964, p. 49; Richards 1933, p. 687; Lease & Lang 1978, p. xi; Fleischmann 1983, p. 284.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 284.

- ^ Quinn 1964, p. 49; Lease & Lang 1978, p. xi.

- ^ a b Lease & Lang 1978, p. xi.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 691.

- ^ Spiller et al. 1963, p. 291.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 676, 686; Richter 2018, pp. 252–253; Martin 1959, p. 467; Sears 1978, p. 73; Morgan 1988, pp. 152, 156.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 694.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 286.

- ^ Morgan 1988, p. 152.

- ^ Sivils 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Richter 2018, pp. 252–253; Richards 1933, p. 691.

- ^ Richter 2018, pp. 252–253; Sears 1978, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 115.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 288.

- ^ Martin 1959, p. 467.

Sources

[edit]- Cairns, William B. (1922). British Criticisms of American Writings 1815–1833: A Contribution to the Study of Anglo-American Literary Relationships. University of Wisconsin Studies in Language and Literature Number 14. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin. OCLC 1833885.

- Cowie, Alexander (1948). The Rise of the American Novel. New York City, New York: American Book Company. OCLC 268679.

- Daggett, Windsor (1920). A Down-East Yankee From the District of Maine. Portland, Maine: A.J. Huston. OCLC 1048477735.

- Fleischmann, Fritz (1983). A Right View of the Subject: Feminism in the Works of Charles Brockden Brown and John Neal. Erlangen, Germany: Verlag Palm & Enke Erlangen. ISBN 978-3-7896-0147-7.

- Gura, Philip F. (2013). Truth's Ragged Edge: The Rise of the American Novel. New York City, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-8090-9445-5.

- Kayorie, James Stephen Merritt (2019). "John Neal (1793–1876)". In Baumgartner, Jody C. (ed.). American Political Humor: Masters of Satire and Their Impact on U.S. Policy and Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 86–91. ISBN 978-1-4408-5486-6.

- King, Peter J. (March 1966). "John Neal as a Benthamite". The New England Quarterly. 39 (1): 47–65. doi:10.2307/363641. JSTOR 363641.

- Lease, Benjamin (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46969-0.

- Lease, Benjamin; Lang, Hans-Joachim, eds. (1978). The Genius of John Neal: Selections from His Writings. Las Vegas: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-261-02382-7.

- Loshe, Lillie Deming (1958) [1907]. The Early American Novel 1789–1830. New York City, New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. OCLC 269646.

- Martin, Harold C. (December 1959). "The Colloquial Tradition in the Novel: John Neal". The New England Quarterly. 32 (4): 455–475. doi:10.2307/362501. JSTOR 362501.

- Merlob, Maya (2012). "Celebrated Rubbish: John Neal and the Commercialization of Early American Romanticism". In Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (eds.). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. pp. 99–122. ISBN 978-1-61148-420-5.

- Morgan, Winifred (1988). An American Icon: Brother Jonathan and American Identity. Newark, New Jersey: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-307-6.

- Neal, John (1825). Brother Jonathan: or, the New Englanders. Edinburgh, Scotland: William Blackwood. OCLC 3593743.

- Orestano, Francesca (1989). "The Old World and the New in the National Landscapes of John Neal". In Gidley, Mick; Lawson-Peebles, Robert (eds.). Views of American Landscapes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–145. ISBN 0-521-36435-3.

- Pethers, Matthew (2012). "'I Must Resemble Nobody': John Neal, Genre, and the Making of American Literary Nationalism". In Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (eds.). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-1-61148-420-5.

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1964) [1936]. American Fiction: An Historical and Critical Survey (Students' ed.). New York City, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc. OCLC 610879015.

- Richards, Irving T. (1933). The Life and Works of John Neal (PhD thesis). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. OCLC 7588473.

- Richter, Jörg Thomas (2018) [Originally published 2009 in Civilizing America: Manners and Civility in American Literature and Culture, edited by Dietmar Schloss. Heidelberg, Germany: Universitätsverlag Winter. pp. 111–132]. "The Willing Suspension of Etiquette: John Neal's Brother Jonathan (1825)". In DiMercurio, Catherine C. (ed.). Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism: Criticism of the Works of Novelists, Philosophers, and Other Creative Writers Who Died between 1800 and 1899, from the First Published Critical Appraisals to Current Evaluations. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale. pp. 249–261. ISBN 978-1-4103-7851-4.

- Schäfer, Stefanie (2016). "UnSettling North America: The Yankee in the Writings of John Neal and Thomas Chandler Haliburton". In Redling, Erik (ed.). Traveling Traditions: Nineteenth-Century Cultural Concepts and Transatlantic Intellectual Networks. Boston, Massachusetts: De Gruyter. pp. 231–246. doi:10.1515/9783110411744-015. ISBN 978-3-11-041174-4.

- Schäfer, Stefanie (2021). Yankee Yarns: Storytelling and the Invention of the National Body in Nineteenth-Century American Culture. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-7744-4.

- Schumacher, Peter (2018). "John Neal 1793–1876". In DiMercurio, Catherine C. (ed.). Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism: Criticism of the Works of Novelists, Philosophers, and Other Creative Writers Who Died between 1800 and 1899, from the First Published Critical Appraisals to Current Evaluations. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale. pp. 155–158. ISBN 978-1-4103-7851-4.

- Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7230-8.

- Sivils, Matthew Wynn (2012). "Chapter 2: "The Herbage of Death": Haunted Environments in John Neal and James Fenimore Cooper". In Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (eds.). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. pp. 39–56. ISBN 978-1-61148-420-5.

- Spiller, Robert E.; Thorp, Willard; Johnson, Thomas H.; Canby, Henry Seidel; Ludwig, Richard M., eds. (1963). The Literary History of the United States: History (3rd ed.). London, UK: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 269181.

- Todd, John M. (1906). A Sketch of the Life of John M. Todd (Sixty-two Years in a Barber Shop) And Reminiscences of His Customers. Portland, Maine: William W. Roberts Co. OCLC 663785.

- Welch, Ellen Bufford (2021). "Literary Nationalism and the Renunciation of the British Gothic Tradition in the Novels of John Neal". Early American Literature. 56 (2): 471–497. doi:10.1353/eal.2021.0039. S2CID 243142175.

External links

[edit]- Brother Jonathan available at Google Books: vol. I, vol. II, vol. III

- Brother Jonathan available at Hathitrust