| Cannabis use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cannabis addiction, marijuana addiction |

| |

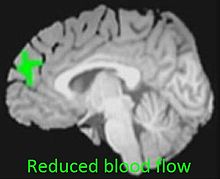

| Reduced blood flow in prefrontal cortex of adolescent cannabis users[1] | |

| Specialty | Addiction medicine, Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Dependency of THC and withdrawal symptoms upon cessation such as anxiety, irritability, depression, depersonalization, restlessness, insomnia, vivid dreams, gastrointestinal problems, and decreased appetite |

| Risk factors | Adolescence and high-frequency use |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy |

| Medication | None approved, experimental only |

Cannabis use disorder (CUD), also known as cannabis addiction or marijuana addiction, is a psychiatric disorder defined in the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and ICD-10 as the continued use of cannabis despite clinically significant impairment.[2][3]

There is a common misconception that cannabis use disorder does not exist.[4][5]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Cannabis use is sometimes comorbid for other mental health problems, such as mood and anxiety disorders, and discontinuing cannabis use is difficult for some users.[6] Psychiatric comorbidities are often present in dependent cannabis users including a range of personality disorders.[7]

Based on annual survey data, some high school seniors who report smoking daily (nearly 7%, according to one study) may function at a lower rate in school than students that do not.[8] The sedating and anxiolytic properties of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in some users might make the use of cannabis an attempt to self-medicate personality or psychiatric disorders.[9]

Dependency

[edit]Prolonged cannabis use produces both pharmacokinetic changes (how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted) and pharmacodynamic changes (how the drug interacts with target cells) to the body. These changes require the user to consume higher doses of the drug to achieve a common desirable effect (known as a higher tolerance), reinforcing the body's metabolic systems for eliminating the drug more efficiently and further down-regulating cannabinoid receptors in the brain.[10]

Cannabis users have shown decreased reactivity to dopamine, suggesting a possible link to a dampening of the reward system of the brain and an increase in negative emotion and addiction severity.[11]

Cannabis users can develop tolerance to the effects of THC. Tolerance to the behavioral and psychological effects of THC has been demonstrated in adolescent humans and animals.[12][13] The mechanisms that create this tolerance to THC are thought to involve changes in cannabinoid receptor function.[12]

One study has shown that between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013, the use of cannabis in the US doubled.[14]

Cannabis dependence develops in about 9% of users, significantly less than that of heroin, cocaine, alcohol, and prescribed anxiolytics,[15] but slightly higher than that for psilocybin, mescaline, or LSD.[16] Of those who use cannabis daily, 10–20% develop dependence.[17]

Withdrawal

[edit]Cannabis withdrawal symptoms occur in half of people being treated for cannabis use disorder.[18] Symptoms may include dysphoria, anxiety, irritability, depression, restlessness, disturbed sleep, gastrointestinal symptoms, and decreased appetite. It is often paired with rhythmic movement disorder. Most symptoms begin during the first week of abstinence and resolve after a few weeks.[6] About 12% of heavy cannabis users showed cannabis withdrawal symptoms as defined by the DSM-5, and this was associated with significant disability as well as mood, anxiety, and personality disorders.[19] Furthermore, a study on 49 dependent cannabis users over a two week period of abstinence proved most prominently symptoms of nightmares and anger issues.[20]

Cause

[edit]Cannabis addiction is often due to prolonged and increasing use of the drug. Increasing the strength of the cannabis taken and increasing use of more effective methods of delivery often increase the progression of cannabis dependency. Approximately 17.0% of weekly and 19.0% of daily cannabis smokers can be classified as cannabis dependent.[21] In addition to cannabis use, it has been shown that co-use of cannabis and tobacco can result in an elevated risk of cannabis use disorder.[22] It can also be caused by being prone to becoming addicted to substances, which can be genetically or environmentally acquired.[23]

Risk factors

[edit]Certain factors are considered to heighten the risk of developing cannabis dependence. Longitudinal studies over a number of years have enabled researchers to track aspects of social and psychological development concurrently with cannabis use. Increasing evidence is being shown for the elevation of associated problems by the frequency and age at which cannabis is used, with young and frequent users being at most risk.[24] The frequency of cannabis use and duration of use are considered to be major risk factors for development of cannabis use disorder. The strength of cannabis used, with higher THC content conferring a heightened risk, is also thought to be a risk factor.[25] Concomitant alcohol or tobacco use, a history of adverse childhood experiences, depression or other psychiatric disorders, stressful life events and parental cannabis use may also increase the risk of developing cannabis use disorder.[25]

The main factors in Australia, for example, related to a heightened risk for developing problems with cannabis use include frequent use at a young age; personal maladjustment; emotional distress; poor parenting; school drop-out; affiliation with drug-using peers; moving away from home at an early age; daily cigarette smoking; and ready access to cannabis. The researchers concluded there is emerging evidence that positive experiences to early cannabis use are a significant predictor of late dependence and that genetic predisposition plays a role in the development of problematic use.[26]

High risk groups

[edit]A number of groups have been identified as being at greater risk of developing cannabis dependence and, in Australia have been found to include adolescent populations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and people with mental health conditions.[27]

Adolescents

[edit]The endocannabinoid system is directly involved in adolescent brain development.[28] Adolescent cannabis users are therefore particularly vulnerable to the potential adverse effects of cannabis use.[28] Adolescent cannabis use is associated with increased cannabis misuse as an adult, issues with memory and concentration, long-term cognitive complications, and poor psychiatric outcomes including social anxiety, suicidality, and addiction.[29][30][31]

There are several reasons why adolescents start a smoking habit. According to a study completed by Bill Sanders, influence from friends, difficult household problems, and experimentation are some of the reasons why this population starts to smoke cannabis.[32] This segment of population seems to be one of the most influenceable group there is.[33] They want to follow the group and look "cool", "hip", and accepted by their friends.[32] This fear of rejection plays a big role in their decision to use cannabis. However it does not seem to be the most important factor. According to a study from Canada, the lack of knowledge about cannabis seems to be the main reason why adolescents start to smoke.[34] The authors observed a high correlation between adolescents that knew about the mental and physical harms of cannabis and their consumption.[34] Of the 1045 young participants in the study, those who could name the least number of negative effects about this drug were usually the ones who were consuming it.[34] They were not isolated cases either. Actually, the study showed that the proportion of teenagers who saw cannabis as a high-risk drug and the ones who thought the contrary was about the same.[35]

Pregnancy

[edit]The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advise against cannabis use during pregnancy or lactation.[36] There is an association between smoking cannabis during pregnancy and low birth weight.[37] Smoking cannabis during pregnancy can lower the amount of oxygen delivered to the developing fetus, which can restrict fetal growth.[37] The active ingredient in cannabis (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, THC) is fat soluble and can enter into breastmilk during lactation.[37] THC in breastmilk can then subsequently be taken up by a breastfeeding infant, as shown by the presence of THC in the infant's feces. However, the evidence for long-term effects of exposure to THC through breastmilk is unclear.[38][39][40]

Diagnosis

[edit]Cannabis use disorder is recognized in the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5),[41] which also added cannabis withdrawal as a new condition.[42] In the 2013 revision for the DSM-5, DSM-IV abuse and dependence were combined into cannabis use disorder. The legal problems criterion (from cannabis abuse) has been removed, and the craving criterion was newly added, resulting in a total of eleven criteria: hazardous use, social/interpersonal problems, neglected major roles, withdrawal, tolerance, used larger amounts/longer, repeated attempts to quit/control use, much time spent using, physical/psychological problems related to use, activities given up and craving. For a diagnosis of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, at least two of these criteria need to be present in the last twelve-month period. Additionally, three severity levels have been defined: mild (two or three criteria), moderate (four or five criteria) and severe (six or more criteria) cannabis use disorder.[43]

Cannabis use disorder is also recognized in the eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11),[44] adding more subdivisions including time intervals of pattern of use (episodic, continuous, or unspecified) and dependence (current, early full remission, sustained partial remission, sustained full remission, or unspecified) compared to the 10th revision.[45]

A 2019 meta-analysis found that 34% of people with cannabis-induced psychosis transitioned to schizophrenia. This was found to be comparatively higher than hallucinogens (26%) and amphetamines (22%).[46]

To screen for cannabis-related problems, several methods are used. Scales specific to cannabis, which provides the benefit of being cost efficient compared to extensive diagnostic interviews, include the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST), Cannabis Use Identification Test (CUDIT), and Cannabis Use Problems Identification Test (CUPIT).[47] Scales for general drug use disorders are also used, including the Severity Dependence Scale (SDS), Drug Use Disorder Identification Test (DUDIT), and Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).[48] However, there are no gold standard and both older and newer scales are still in use.[48] To quantify cannabis use, methods such as Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) and Cannabis Use Daily (CUD) are used.[48] These methods measure general consumption and not grams of psychoactive substance as the concentration of THC may vary among drug users.[48]

Treatment

[edit]Clinicians differentiate between casual users who have difficulty with drug screens, and daily heavy users, to a chronic user who uses multiple times a day.[9] In the US, as of 2013[update], cannabis is the most commonly identified illicit substance used by people admitted to treatment facilities.[17] Demand for treatment for cannabis use disorder increased internationally between 1995 and 2002.[49] In the United States, the average adult who seeks treatment has consumed cannabis for over 10 years almost daily and has attempted to quit six or more times.[16]

Treatment options for cannabis dependence are far fewer than for opioid or alcohol dependence. Most treatment falls into the categories of psychological or psychotherapeutic, intervention, pharmacological intervention or treatment through peer support and environmental approaches.[26] No medications have been found effective for cannabis dependence,[50] but psychotherapeutic models hold promise.[6] Screening and brief intervention sessions can be given in a variety of settings, particularly at doctor's offices, which is of importance as most cannabis users seeking help will do so from their general practitioner rather than a drug treatment service agency.[51]

The most commonly accessed forms of treatment in Australia are 12-step programmes, physicians, rehabilitation programmes, and detox services, with inpatient and outpatient services equally accessed.[52] In the EU approximately 20% of all primary admissions and 29% of all new drug clients in 2005, had primary cannabis problems. And in all countries that reported data between 1999 and 2005 the number of people seeking treatment for cannabis use increased.[53]

Psychological

[edit]Psychological intervention includes cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy (MET), contingency management (CM), supportive-expressive psychotherapy (SEP), family and systems interventions, and twelve-step programs.[6][54]

Evaluations of Marijuana Anonymous programs, modelled on the 12-step lines of Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, have shown small beneficial effects for general drug use reduction.[55] In 2006, the Wisconsin Initiative to Promote Healthy Lifestyles implemented a program that helps primary care physicians identify and address marijuana use problems in patients.[56]

Medication

[edit]As of 2023, there is no medication that has been proven effective for treating cannabis use disorder, research is focused on three treatment approaches: agonist substitution, antagonist, and modulation of other neurotransmitter systems.[6][50][25] More broadly, the goal of medication therapy for cannabis use disorder centers around targeting the stages of the addiction: acute intoxication/binge, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation.[57]

For the treatment of the withdrawal/negative affect symptom domain of cannabis use disorder, medications may work by alleviating restlessness, irritable or depressed mood, anxiety, and insomnia.[58] Bupropion, which is a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been studied for the treatment of withdrawal with largely poor results.[58] Atomoxetine has also shown poor results, and is as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, though it does increase the release of dopamine through downstream effects in the prefrontal cortex (an area of the brain responsible for planning complex tasks and behavior).[58] Venlafaxine, a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, has also been studied for cannabis use disorder, with the thought that the serotonergic component may be useful for the depressed mood or anxious dimensions of the withdrawal symptom domain.[58] While venlafaxine has been shown to improve mood for people with cannabis use disorder, a clinical trial in this population actually found worse cannabis abstinence rates compared to placebo.[58] It is worth noting that venlafaxine is sometimes poorly tolerated, and infrequent use or abrupt discontinuation of its use can lead to withdrawal symptoms from the medication itself, including irritability, dysphoria, and insomnia.[59] It is possible that venlafaxine use actually exacerbated cannabis withdrawal symptoms, leading people to use more cannabis than placebo to alleviate their discomfort.[58] Mirtazapine, which increases serotonin and norepinephrine, has also failed to improve abstinence rates in people with cannabis use disorder.[58]

People sometimes use cannabis to cope with their anxiety, and cannabis withdrawal can lead to symptoms of anxiety.[58] Buspirone, a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist, has shown limited efficacy for treating anxiety in people with cannabis use disorder, though there may be better efficacy in males than in females.[58] Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), has failed to show efficacy in adolescents with both cannabis use disorder and depression.[58] SSRIs are a class of antidepressants that are also used for the treatment of anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder.[60] Vilazodone, which has both SRI and 5-HT1A receptor agonism properties, also failed to increase abstinence rates in people with cannabis use disorder.[58]

Studies of valproate have found no significant benefit, though some studies have found mixed results.[58] Baclofen, a GABAB receptor agonist and antispasmodic medication, has been found to reduce cravings but without a significant benefit towards preventing relapse or improving sleep.[58] Zolpidem, a GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulator and "z-drug" medication, has shown some efficacy in treating insomnia due to cannabis withdrawal, though there is a potential for misuse.[58] Entacapone was well tolerated and decreased cannabis cravings in a trial on a small number of patients.[6] Topiramate, an antiepileptic drug, has shown mixed results in adolescents, reducing the volume of cannabis consumption without significantly increasing abstinence, with somewhat poor tolerability.[58] Gabapentin, an indirect GABA modulator, has shown some preliminary benefit for reducing cravings and cannabis use.[58]

The agonist substitution approach is one that draws upon the analogy of the success of nicotine replacement therapy for nicotine addiction. Dronabinol, which is synthetic THC, has shown benefit in reducing cravings and other symptoms of withdrawal, though without preventing relapse or promoting abstinence.[58] Combination therapy with dronabinol and the α2-adrenergic receptor agonist lofexidine have shown mixed results, with possible benefits towards reducing withdrawal symptoms.[58] However, overall, the combination of dronabinol and lofexidine is likely not effective for the treatment of cannabis use disorder.[58] Nabilone, a synthetic THC analogue, has shown benefits in reducing symptoms of withdrawal such as difficulty sleeping, and decreased overall cannabis use.[58] Despite its psychoactive effects, the slower onset of action and longer duration of action of nabilone make it less likely to be abused than cannabis itself, which makes nabilone a promising harm reduction strategy for the treatment of cannabis use disorder.[58] The combination of nabilone and zolpidem has been shown to decrease sleep-related and mood-related symptoms of cannabis withdrawal, in addition to decreasing cannabis use.[58] Nabiximols, a combined THC and cannabidiol (CBD) product that is formulated as an oromucosal spray, has been shown to improve withdrawal symptoms without improving abstinence rates.[58] Oral CBD has not shown efficacy in reducing the signs or symptoms of cannabis use, and likely has no benefit in cannabis use withdrawal symptoms.[58] The CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant has shown efficacy in reducing the effects of cannabis in users, but with a risk for serious psychiatric side effects.[58]

Naltrexone, a μ-opioid receptor antagonist, has shown mixed results for cannabis use disorder—both increasing the subjective effects of cannabis when given acutely, but potentially decreasing the overall use of cannabis with chronic administration.[58] N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has shown some limited benefit in decreasing cannabis use in adolescents, though not with adults.[58] Lithium, a mood stabilizer, has shown mixed results for treating symptoms of cannabis withdrawal, but is likely ineffective.[58] Quetiapine, an atypical antipsychotic, has been shown to treat cannabis withdrawal related insomnia and decreased appetite at the expense of exacerbating cravings.[58] Oxytocin, a neuropeptide that the body produces, has shown some benefit in reducing the use of cannabis when administered intranasally in combination with motivational enhancement therapy sessions, though the treatment effect did not persist between sessions.[58]

CB1 receptor antagonists such as rimonabant have been tested for utility in CUD.[61]

Barriers to treatment

[edit]Research that looks at barriers to cannabis treatment frequently cites a lack of interest in treatment, lack of motivation and knowledge of treatment facilities, an overall lack of facilities, costs associated with treatment, difficulty meeting program eligibility criteria and transport difficulties.[dubious – discuss][62][63][64]

Epidemiology

[edit]According to the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis is one of the most widely used drugs in the world.[65] Research by the Pew Research Center from 2012 claims 42% of the US population have claimed to use cannabis at some point.[3] According to the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 46% of U.S. adults say they have ever used cannabis.[66] An estimated 9% of those who use cannabis develop dependence.[16][67][needs update]

In the United States, cannabis is the most commonly identified illicit substance used by people admitted to treatment facilities.[6] Most of these people were referred there by the criminal justice system. Of admittees, 16% either went on their own, or were referred by family or friends.[68]

Of Australians aged 14 years and over, 34.8% have used cannabis one or more times in their life.[69]

In the European Union (data as available in 2018, information for individual countries was collected between 2012 and 2017), 26.3% of adults aged 15–64 used cannabis at least once in their lives, and 7.2% used cannabis in the last year. The highest prevalence of cannabis use among 15 to 64 years old in the EU was reported in France, with 41.4% having used cannabis at least once in their life, and 2.17% used cannabis daily or almost daily. Among young adults (15–34 years old), 14.1% used cannabis in the last year.[70]

Among adolescents (15–16 years old) in a European school based study (ESPAD), 16% of students have used cannabis at least once in their life, and 7% (boys: 8%, girls: 5%) of students had used cannabis in the last 30 days.[71]

Globally, 22.1 million people (0.3% of the worlds population) were estimated to have cannabis dependence.[72]

Research

[edit]Medications such as SSRI antidepressants, mixed-action antidepressants, bupropion, buspirone, and atomoxetine may not be helpful to treat cannabis use disorder, but the evidence is very weak and further research is required.[50] THC preparations, gabapentin, oxytocin, and N-acetylcysteine also require more research to determine if they are effective as the evidence base is weak.[50]

Heavy cannabis use has been associated with impaired cognitive functioning; however, its specific details are difficult to elucidate due to the potential use of additional substances of users, and lack of longitudinal studies.[73]

See also

[edit]- La Guardia Committee, the first in-depth study into the effects of cannabis.

- Medical cannabis

- Quitting smoking

References

[edit]- ^ Jacobus, Joanna; Goldenberg, Diane; Wierenga, Christina E.; Tolentino, Neil J.; Liu, Thomas T.; Tapert, Susan F. (1 August 2012). "Altered cerebral blood flow and neurocognitive correlates in adolescent cannabis users". Psychopharmacology. 222 (4): 675–684. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2674-4. ISSN 1432-2072. PMC 3510003. PMID 22395430.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse (2014), The Science of Drug Abuse and Addiction: The Basics, archived from the original on 1 April 2022, retrieved 17 March 2016

- ^ a b Gordon AJ, Conley JW, Gordon JM (December 2013). "Medical consequences of marijuana use: a review of current literature". Current Psychiatry Reports (Review). 15 (12): 419. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0419-7. PMID 24234874. S2CID 29063282.

- ^ Smith, Dana (10 April 2023). "How Do You Know if You're Addicted to Weed?". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ MacDonald, Kai (1 April 2016). "Why Not Pot?: A Review of the Brain-based Risks of Cannabis". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 13 (3–4): 13–22. PMC 4911936. PMID 27354924.

- ^ a b c d e f g Danovitch I, Gorelick DA (June 2012). "State of the art treatments for cannabis dependence". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America (Review). 35 (2): 309–26. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.003. PMC 3371269. PMID 22640758.

- ^ Dervaux A, Laqueille X (December 2012). "[Cannabis: Use and dependence]". Presse Médicale (in French). 41 (12 Pt 1): 1233–40. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.07.016. PMID 23040955.

- ^ E.B., Robertson. "Information on Cannabis Addiction". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b Clinical Textbook of Addictive Disorders, Marijuana, David McDowell, page 169, Published by Guilford Press, 2005 ISBN 1-59385-174-X.

- ^ Hirvonen J, Goodwin RS, Li CT, Terry GE, Zoghbi SS, Morse C, et al. (June 2012). "Reversible and regionally selective downregulation of brain cannabinoid CB1 receptors in chronic daily cannabis smokers". Molecular Psychiatry. 17 (6): 642–9. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.82. PMC 3223558. PMID 21747398.

- ^ Madras BK (August 2014). "Dopamine challenge reveals neuroadaptive changes in marijuana abusers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (33): 11915–6. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11111915M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1412314111. PMC 4143049. PMID 25114244.

- ^ a b González S, Cebeira M, Fernández-Ruiz J (June 2005). "Cannabinoid tolerance and dependence: a review of studies in laboratory animals". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 81 (2): 300–18. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.028. PMID 15919107. S2CID 23328509.

- ^ Maldonado R, Berrendero F, Ozaita A, Robledo P (May 2011). "Neurochemical basis of cannabis addiction". Neuroscience. 181: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.035. PMID 21334423. S2CID 6660057.

- ^ "Marijuana use disorder is common and often untreated". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Wilkie G, Sakr B, Rizack T (May 2016). "Medical Marijuana Use in Oncology: A Review". JAMA Oncology. 2 (5): 670–675. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0155. PMID 26986677.

- ^ a b c Budney AJ, Roffman R, Stephens RS, Walker D (December 2007). "Marijuana dependence and its treatment". Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 4 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1151/ascp07414. PMC 2797098. PMID 18292704.

- ^ a b Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS (February 2013). "The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis". Pharmacotherapy (Review). 33 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1002/phar.1187. PMID 23386598. S2CID 8503107.

- ^ Bahji, Anees; Stephenson, Callum; Tyo, Richard; Hawken, Emily R.; Seitz, Dallas P. (9 April 2020). "Prevalence of Cannabis Withdrawal Symptoms Among People With Regular or Dependent Use of Cannabinoids". JAMA Network Open. 3 (4): e202370. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2370. PMC 7146100. PMID 32271390.

- ^ Livne O, Shmulewitz D, Lev-Ran S, Hasin DS (February 2019). "DSM-5 cannabis withdrawal syndrome: Demographic and clinical correlates in U.S. adults". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 195: 170–177. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.005. PMC 6359953. PMID 30361043.

- ^ Allsop, David (2011). "The Cannabis Withdrawal Scale development: Patterns and predictors of cannabis withdrawal and distress". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 119 (1–2): 123–129. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.003. PMID 21724338. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Cougle, Jesse R.; Hakes, Jahn K.; Macatee, Richard J.; Zvolensky, Michael J.; Chavarria, Jesus (27 April 2016). "Probability and Correlates of Dependence Among Regular Users of Alcohol, Nicotine, Cannabis, and Cocaine: Concurrent and Prospective Analyses of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 77 (4): e444 – e450. doi:10.4088/JCP.14m09469. PMID 27137428.

- ^ Connor, Jason P.; Stjepanović, Daniel; Le Foll, Bernard; Hoch, Eva; Budney, Alan J.; Hall, Wayne D. (25 February 2021). "Cannabis use and cannabis use disorder". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 7 (1): 3. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00247-4. ISSN 2056-676X. PMC 8655458. PMID 33627670.

- ^ Coffey C, Carlin JB, Lynskey M, Li N, Patton GC (April 2003). "Adolescent precursors of cannabis dependence: findings from the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 182 (4): 330–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.182.4.330. PMID 12668409.

- ^ "DrugFacts: Marijuana". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Gorelick, David A. (14 December 2023). "Cannabis-Related Disorders and Toxic Effects". New England Journal of Medicine. 389 (24): 2267–2275. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2212152. PMID 38091532.

- ^ a b Copeland J, Gerber S, Swift W (December 2004). Evidence-based answers to cannabis questions a review of the literature. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre University of New South Wales, A report prepared for the Australian National Council on Drugs.

- ^ McLaren, J, Mattick, R P., Cannabis in Australia Use, supply, harms, and responses Monograph series No. 57 Report prepared for: Drug Strategy Branch Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre University of New South Wales, Australia.

- ^ a b Volkow, Nora D.; Swanson, James M.; Evins, A. Eden; DeLisi, Lynn E.; Meier, Madeline H.; Gonzalez, Raul; Bloomfield, Michael A. P.; Curran, H. Valerie; Baler, Ruben (1 March 2016). "Effects of Cannabis Use on Human Behavior, Including Cognition, Motivation, and Psychosis: A Review" (PDF). JAMA Psychiatry. 73 (3): 292–7. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3278. ISSN 2168-622X. PMID 26842658.

- ^ Levine, Amir; Clemenza, Kelly; Rynn, Moira; Lieberman, Jeffrey (1 March 2017). "Evidence for the Risks and Consequences of Adolescent Cannabis Exposure". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 56 (3): 214–225. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.12.014. ISSN 0890-8567. PMID 28219487.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (U.S.). Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: an Evidence Review and Research Agenda. (2017). The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids : the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. The National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-45304-2. OCLC 1021254335.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Montoya, Ivan D.; Weiss, Susan R. B. (2018). Cannabis use disorders (1 ed.). New York, NY: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-319-90364-4. OCLC 1029794724.

- ^ a b SANDERS, Bill (2005). Youth Crime and Youth Culture in the Inner City. Taylor and Francis Group.

- ^ LEMIRE, L. (2014). Enquête québécoise sur la santé des jeunes du secondaire 2010-2011. Santé publique. Récupéré de http://www.cisss-lanaudiere.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/internet/cisss_lanaudiere/Documentation/Sante_publique/Themes/Sante_mentale_et_psychosociale/EQSJS-Envir_social-Amis-VF.pdf

- ^ a b c LEOS-TORO, C., FONG, G. T., MEYER, S. B. et HAMMOND, D. (2020). Cannabis health knowledge and risk perceptions among Canadian youth and young adults. Harm Reduction Journal. London. Vol. 17. (p.1-13).

- ^ LEOS-TORO, C., FONG, G. T., MEYER, S. B. et HAMMOND, D. (2020). Cannabis health knowledge and risk perceptions among Canadian youth and young adults. Harm Reduction Journal. London. Vol. 17. (p.1-13)

- ^ "Committee Opinion No. 722: Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 130 (4): e205 – e209. October 2017. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002354.

- ^ a b c Gunn, J K L; Rosales, C B; Center, K E; Nuñez, A; Gibson, S J; Christ, C; Ehiri, J E (2016). "Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 6 (4): e009986. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009986. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 4823436. PMID 27048634.

- ^ Metz, Torri D.; Stickrath, Elaine H. (December 2015). "Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (6): 761–778. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.025. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 25986032.

- ^ Brown, R.A.; Dakkak, H.; Seabrook, J.A. (21 December 2018). "Is Breast Best? Examining the effects of alcohol and cannabis use during lactation". Journal of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. 11 (4): 345–356. doi:10.3233/npm-17125. ISSN 1934-5798. PMID 29843260. S2CID 44153511.

- ^ Seabrook, J.A.; Biden, C.; Campbell, E. (2017). "Does the risk of exposure to marijuana outweigh the benefits of breastfeeding? A systematic review". Canadian Journal of Midwifery Research and Practice. 16 (2): 8–16.

- ^ "Proposed Revision | APA DSM-5". Dsm5.org. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "DSM-5 Now Categorizes Substance Use Disorder in a Single Continuum". American Psychiatric Association. 17 May 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Hasin DS, O'Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, et al. (August 2013). "DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (8): 834–51. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. PMC 3767415. PMID 23903334.

- ^ "ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "ICD-10 Version:2016". icd.who.int. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ Murrie, Benjamin; Lappin, Julia; Large, Matthew; Sara, Grant (16 October 2019). "Transition of Substance-Induced, Brief, and Atypical Psychoses to Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (3): 505–516. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz102. PMC 7147575. PMID 31618428.

- ^ Casajuana, Cristina; López-Pelayo, Hugo; Balcells, María Mercedes; Miquel, Laia; Colom, Joan; Gual, Antoni (2016). "Definitions of Risky and Problematic Cannabis Use: A Systematic Review". Substance Use & Misuse. 51 (13): 1760–1770. doi:10.1080/10826084.2016.1197266. ISSN 1532-2491. PMID 27556867. S2CID 32299878.

- ^ a b c d López-Pelayo, H.; Batalla, A.; Balcells, M. M.; Colom, J.; Gual, A. (2015). "Assessment of cannabis use disorders: a systematic review of screening and diagnostic instruments". Psychological Medicine. 45 (6): 1121–1133. doi:10.1017/S0033291714002463. ISSN 1469-8978. PMID 25366671. S2CID 206254638.

- ^ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. (2003). Emergency department trends from the drug abuse warning network, final estimates 1995–2002, DAWN Series: D-24, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 03-3780.

- ^ a b c d Nielsen S, Gowing L, Sabioni P, Le Foll B (January 2019). "Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (3): CD008940. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008940.pub3. PMC 6360924. PMID 30687936.

- ^ Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M (2000). Cannabis use and mental health among Australian adults: Findings from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being, NDARC Technical Report No. 98. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales.

- ^ Copeland J, Swift W (April 2009). "Cannabis use disorder: epidemiology and management". International Review of Psychiatry (Review). 21 (2): 96–103. doi:10.1080/09540260902782745. PMID 19367503. S2CID 10881676.

- ^ EMCDDA (2007). Annual report 2007: The state of the drugs problem in Europe. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- ^ Gates, Peter J.; Sabioni, Pamela; Copeland, Jan; Le Foll, Bernard; Gowing, Linda (5 May 2016). "Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD005336. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005336.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4914383. PMID 27149547.

- ^ Sussman, Steve (1010). "A Review of Alcoholics Anonymous/Narcotics Anonymous Programs for Teens". Evaluation & the Health Professions. 33 (1): 26–55. doi:10.1177/0163278709356186. PMC 4181564. PMID 20164105.

- ^ "With Support From Collaborative, Primary Care Practices Identify and Address Behavioral Health Issues, Reducing Binge Drinking, Marijuana Use, and Depression Symptoms". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Zehra A, Burns J, Liu CK, Manza P, Wiers CE, Volkow ND, Wang GJ (December 2018). "Cannabis Addiction and the Brain: a Review". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 13 (4): 438–452. doi:10.1007/s11481-018-9782-9. PMC 6223748. PMID 29556883.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Brezing CA, Levin FR (January 2018). "The Current State of Pharmacological Treatments for Cannabis Use Disorder and Withdrawal". Neuropsychopharmacology. 43 (1): 173–194. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.212. PMC 5719115. PMID 28875989.

- ^ Fava GA, Benasi G, Lucente M, Offidani E, Cosci F, Guidi J (2018). "Withdrawal Symptoms after Serotonin-Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitor Discontinuation: Systematic Review" (PDF). Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 87 (4): 195–203. doi:10.1159/000491524. PMID 30016772. S2CID 51677365.

- ^ "Generalised anxiety disorder – NICE Pathways". pathways.nice.org.uk. NICE. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ Sabioni, Pamela; Le Foll, Bernard (2018). "Psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for the treatment of cannabis use disorder". F1000Research. 7: 173. doi:10.12688/f1000research.11191.1. ISSN 2046-1402. PMC 5811668. PMID 29497498.

- ^ Treloar C, Holt M (2006). "Deficit models and divergent philosophies: Service providers' perspectives on barriers and incentives to drug treatment". Drugs: Education Prevention and Policy. 13 (4): 367–382. doi:10.1080/09687630600761444. S2CID 73095850.

- ^ Treloar C, Abelson J, Cao W, Brener L, Kippax S, Schultz L, Schultz M, Bath N (2004). Barriers and incentives to treatment for illicit drug users. Monograph Series 53. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, National Drug Strategy.

- ^ Gates P, Taplin S, Copeland J, Swift W, Martin G (2008). "Barriers and Facilitators to Cannabis Treatment". Drug and Alcohol Review. 31 (3). National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney: 311–9. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00313.x. PMID 21521384.

- ^ "WDR 2022_Booklet 2". United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ "6 facts about marijuana". 10 April 2024.

- ^ Marshall K, Gowing L, Ali R, Le Foll B (17 December 2014). "Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD008940. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008940.pub2. PMC 4297244. PMID 25515775.

- ^ "Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS)2001 – 2011. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services" (PDF). samhsa.gov. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "Drug Info". Australian Drug Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Statistical Bulletin 2018 — prevalence of drug use | www.emcdda.europa.eu". emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Summary | www.espad.org". espad.org. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, Santomauro D, Erskine H, Mantilla-Herrara A, et al. (GBD 2016 Alcohol and Drug Use Collaborators) (December 2018). "The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (12): 987–1012. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7. PMC 6251968. PMID 30392731.

- ^ Scott, JC; Slomiak, ST; Jones, JD; Rosen, AFG; Moore, TM; Gur, RC (1 June 2018). "Association of Cannabis With Cognitive Functioning in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 75 (6): 585–595. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0335. PMC 6137521. PMID 29710074.