Casey Jones | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Luther Jones March 14, 1863 Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | April 30, 1900 (aged 37) Vaughan, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Train wreck |

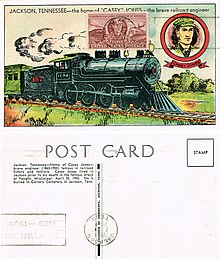

| Burial place | Mount Calvary Cemetery, Jackson, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | John Jones |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1878–1900 |

| Spouse |

Mary Joanna Brady (m. 1886) |

| Children | 3 |

John Luther "Casey" Jones (March 14, 1863 – April 30, 1900) was an American railroader who was killed when his passenger train collided with a stalled freight train in Vaughan, Mississippi.

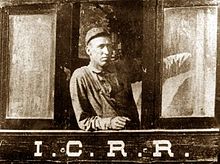

Jones was a locomotive engineer for the Illinois Central Railroad, based in Memphis, Tennessee, and Jackson, Mississippi. He was noted for his exceptionally punctual schedules, which sometimes required a degree of risk, though this was not a factor on his fatal last journey. However, there is some disagreement about the sequence of events on that night, April 29–30, 1900.

He was due to run the southbound passenger service from Memphis to Canton, Mississippi, departing 11:35 p.m. Owing to the absence of another engineer, he had to take over another service through the day, which may have deprived him of sleep. He eventually departed 75 minutes late, but was confident of making up the time with the powerful ten-wheeler Engine No. 382, known as "Cannonball". This was then later referenced in a New York newspaper to describe Erwin Baker and his now infamous "Cannonball Run".[1]

Approaching Vaughan at high speed, he was unaware that three trains were occupying the station, one of which was broken down and directly on his line. Some claim that he ignored a flagman signaling to him, though this person may have been out of sight on a tight bend or obscured by fog. All are agreed, however, that Jones managed to avert a potentially disastrous crash through his exceptional skill at slowing the engine and saving the lives of the passengers at the cost of his own. For this, he was immortalized in a traditional song, "The Ballad of Casey Jones".

Family background

[edit]Jones was born in rural southeastern Missouri. The Jones family moved to Cayce, Kentucky[2] after his mother Ann Nolan Jones and his father Frank Jones, a schoolteacher, decided that the rural areas of Missouri offered few opportunities for their family.[3] It was there that he acquired the nickname of "Cayce", which he chose to spell as "Casey".[4]

Jones met his wife Mary Joanna "Janie" Brady through her father, who owned the boarding house where Jones was staying. Since she was Catholic, he decided to convert and was baptized on November 11, 1886, at St. Bridget's Catholic Church in Whistler, Alabama[5][6] to please her. They were married at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Jackson, Tennessee, on November 25, 1886. They bought a house at West Chester Street in Jackson, Tennessee, where they raised their three children.[7] By all accounts he was a devoted family man and teetotaler.[citation needed]

Promotion to engineer

[edit]Jones went to work for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad as a telegraph operator, performed well, and was promoted to brakeman on the Columbus, Kentucky, to Jackson, Tennessee route, and then to fireman on the Jackson, Tennessee to Mobile, Alabama, route.[8]

In the summer of 1887, a yellow fever epidemic struck many train crews on the neighboring Illinois Central Railroad (IC), providing an unexpected opportunity for faster promotion of firemen on that line. On March 1, 1888, Jones switched to IC, firing a freight locomotive between Jackson, Tennessee and Water Valley, Mississippi.

He was promoted to engineer, his lifelong goal, on February 23, 1891. Jones reached the pinnacle of the railroad profession as an expert locomotive engineer for IC. Railroading was a talent, and Jones was recognized by his peers as one of the best engineers in the business. He was known for his insistence that he "get her there on the advertised [time]" and that he never "fall down", meaning he never arrived at his destination behind schedule. He was so punctual, it was said that people set their watches by him.[citation needed]

His work in Jackson primarily involved freight service between Jackson and Water Valley, Mississippi. Both locations were busy and important stops for IC, and he developed close ties with them between 1890 and 1900.[7]

Service at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893

[edit]During the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, in 1893, IC was charged with providing commuter service for the thousands of visitors to the fairground. A call was sent out for trainmen who wanted to work there. Jones answered it, spending the summer there with his wife. He shuttled many people from Van Buren Street to Jackson Park during the exposition. It was his first experience as an engineer in passenger service and he enjoyed it.[8]

At the Exposition, he became acquainted with No. 638, a new freight engine IC had on display as the latest and greatest technological advancement in locomotives. It had eight drive wheels and two pilot wheels, a 2-8-0 "Consolidation" type. At the closing of the fair, No. 638 was due to be sent to Water Valley for service in the Jackson District. Jones asked for permission to drive the engine back to Water Valley. His request was approved, and No. 638 ran its first 589 miles (948 km) with Jones at the throttle to Water Valley. Jones liked No. 638 and liked working in the Jackson District because his family was there. They had once moved to Water Valley, but returned to Jackson, which they felt was home.

Jones drove the engine until he transferred to Memphis in February 1900. No. 638 stayed in Water Valley. That year, he drove the engine that became most closely associated with him one time. That was Engine No. 382, known affectionately as "Ole 382.", or "Cannonball". It was a steam-driven Rogers 4-6-0 "Ten Wheeler" with six drivers, each approximately six feet (1.8 m) high. Bought new in 1898 from the Rogers Locomotive Works, it was a very powerful engine for the time.

His regular fireman on No. 638 was his close friend John Wesley McKinnie, with whom he worked exclusively from about 1897 until he switched to the passenger run out of Memphis. There he worked with his next and last fireman, Simeon T. "Sim" Webb in 1900.[8]

Rescue of a child from the tracks

[edit]A little-known example of Jones's heroic instincts in action is described by his biographer and friend Fred J. Lee in his book Casey Jones: Epic of the American Railroad (1939). He recounts an incident in 1895 as Jones's train approached Michigan City, Mississippi. He had left the cab with a fellow engineer Bob Stevenson, who had reduced speed sufficiently for Jones to walk safely out on the running board to oil the relief valves. He advanced from the running board to the steam chest and then to the pilot beam to adjust the spark screen. He had finished well before they arrived at the station, as planned, and was returning to the cab when he noticed a group of small children dart in front of the train some 60 yards (55 m) ahead. All cleared the rails easily except for a little girl who suddenly froze in fear at the sight of the oncoming locomotive. Jones shouted to Stevenson to reverse the train and yelled to the girl to get off the tracks in almost the same breath. Realizing that she was still immobile, he raced to the tip of the pilot (cowcatcher) and braced himself on it, reaching out as far as he could to pull the frightened but unharmed girl from the rails. The event was partially spoofed in The Brave Engineer, in which the hero rescued a damsel from a cliché bandit.[8][dubious – discuss]

Baseball player

[edit]Jones was an avid baseball fan and watched or participated in the game whenever his schedule allowed. During the 1880s, he had played in Columbus, Kentucky, while he was a club operator on the M & O. One Sunday during the summer of 1898, the Water Valley shop team was scheduled to play the Jackson shop team and Jones got to haul the team to Jackson for the game.[8]

Rules infractions

[edit]Jones was issued nine citations for rules infractions in his career, with a total of 145 days suspended. But in the year prior to his death, Jones had not been cited for any rules infractions. Railroaders who worked with Jones liked him but admitted that he was a bit of a risk-taker. Unofficially though, the penalties were far more severe for running behind than breaking the rules[citation needed]. He was by all accounts an ambitious engineer, eager to move up the seniority ranks and serve on the better-paying, more prestigious passenger trains.

Transfer to passenger trains

[edit]In February 1900, Jones was transferred from Jackson, Tennessee to Memphis, Tennessee, for the passenger run between Memphis and Canton, Mississippi. This was one link of a four-train run between Chicago, Illinois, and New Orleans, Louisiana, the so-called "cannonball" passenger run. "Cannonball" was a contemporary term applied to fast mail and fast passenger trains of those days, but it was a generic term for speed service. This run offered the fastest schedules in the history of American railroading. Some veteran engineers doubted the times could be met and some quit.[7]

Engineer Willard W. "Bill" Hatfield had transferred from Memphis back to a run out of Water Valley, thus opening up trains No. 2 (north) and No. 3 (south) to another engineer. Jones had to move his family to Memphis and give up working with his close friend John Wesley McKinnie on No. 638, but he thought the change was worth it. Jones would drive Hatfield's Engine No. 382 until his death in 1900.[8]

Fatal accident

[edit]

There is disagreement over the circumstances prior to Casey Jones's fatal last run. In the account given in the book Railroad Avenue by Freeman H. Hubbard, which was based on an interview with fireman Sim Webb, he and Casey had been used extra on trains 3 and 2 to cover for engineer Sam Tate, who had marked off ill. They returned to Memphis at 6:25 a.m. on April 29. This gave them adequate time to be rested for No. 1 that night, which was their regular assigned run.[9]

The Fred J. Lee biography Casey Jones contended that the men arrived in Memphis on No. 4 at 9 p.m. April 29. They were asked to turn around and take No. 1 back to Canton to fill in for Sam Tate, who had marked off. This would have given them little time to rest, as No. 1 was due out at 11:35 p.m. In both accounts, Jones's regular run included trains 1 and 4.[10]

In a third account, trains 3 and 2 were Jones and Webb's regular run, and they were asked to fill in for Sam Tate that night on No. 1, having arrived that morning on No. 2.[8]

In any event, they departed Memphis on the fatal run at 12:50 a.m., 75 minutes behind schedule owing to No. 1's late arrival. The crew felt the conditions of the run, including a fast engine, a good fireman, a light train, and rainy or damp weather, were ideal for a record-setting run. The weather was foggy, reducing visibility, and the run was well known for its tricky curves.[7][8]

In the first section of the run, Jones drove from Memphis 100 miles (160 km) south to Grenada, Mississippi, with an intermediate water stop at Sardis, Mississippi, over a new section of light and shaky rails at speeds of up to 80 miles per hour (130 km/h). By the time Jones arrived at Grenada for another water stop, he had made up 55 minutes of the 75-minute delay.

Jones made up another 15 minutes in the 25-mile (40 km) stretch from Grenada to Winona, Mississippi. By the time he got to Durant, Mississippi, Jones was almost on time. He was quite happy, saying at one point, "Sim, the old girl's got her dancing slippers on tonight!" as he leaned on the Johnson bar.

At Durant, he received new orders to take to the siding at Goodman, Mississippi (8 miles (13 km) south of Durant), wait for the No. 2 passenger train to pass, and then continue on to Vaughan. Furthermore, he was informed he would meet local No. 26 passenger train at Vaughan (15 miles (24 km) south of Goodman). He was told No. 26 was in two sections and would be on the siding, so he would take priority over it. Jones pulled out of Goodman only five minutes behind schedule. With 25 miles (40 km) of fast track ahead, Jones likely felt he had a good chance to make it to Canton by 4:05 am "on the advertised".[7][8]

Unbeknownst to Jones, three separate trains were in the station at Vaughan. The No. 83, a double-header freight train (located to the north and headed south), which had been delayed, and the No. 72, a long freight train (located to the south and headed north), were both on the passing track to the east of the main line. The combined length of the two trains was ten cars longer than the length of the east passing track, causing some of the cars to be stopped on the main line. The two sections of No. 26 had arrived from Canton earlier, and required a saw-by maneuver to get to the house track west of the main line. The saw-by maneuver required No. 83 to back up onto the main line, to allow No. 72 to move northward and pull its overlapping cars off the main line and onto the east side track from the south switch. This allowed the two sections of No. 26 to gain access to the house track. The saw-by, however, left the rear cars of No. 83 overlapping above the north switch and on the main line, directly in Jones' path. As workers prepared a second saw-by to let Jones pass, an air hose broke on No. 72, locking its brakes and leaving the last four cars of No. 83 on the main line.[7][8]

At the same time, Jones, who was almost back on schedule, was running at about 75 miles per hour (120 km/h) toward Vaughan. As Jones and Webb approached the station, they went through a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) left-hand curve that blocked Jones' view from the engine's right side. Webb's view from the left side was better, and he was first to see the red lights of the caboose on the main line. He alerted Jones, who ordered him to jump from the train. Webb leapt out about 300 feet (90 m) before impact, and was knocked unconscious. The last thing he heard as he jumped was the long, piercing whistle used by Jones to warn anyone still in the freight train looming ahead. At that point, Jones was only two minutes behind schedule.[7][8]

Jones reversed the throttle and slammed the airbrakes into emergency stop, but the engine quickly plowed through several loaded train cars before derailing. He had been able to reduce his speed to about 40 miles per hour (60 km/h) before impact. It's believed Jones' actions prevented any other serious injury and death; Jones was the only fatality of the collision. His watch stopped at the time of impact, 3:52 a.m. Popular legend holds his hands still clutched the whistle cord and brake when his body was pulled from the wreckage.

The next morning, Jones's body was transported to Jackson, Tennessee by the No. 26 passenger train. A funeral service was held May 2, 1900, at St. Mary's Church, where he and Janie Brady had married 14 years before. He was buried in Mount Calvary Cemetery. A record 15 enginemen rode 118 miles (190 km) from Water Valley to pay their last respects.[8]

Coverage of the accident

[edit]The headlines in The Jackson Sun (Jackson, Tennessee) read: "FATAL WRECK – Engineer Casey Jones, of This City, Killed Near Canton, Miss. – DENSE FOG THE DIRECT CAUSE – Of a Rear End Collision on the Illinois Central. – Fireman and Messenger Injured – Passenger Train Crashed Into a Local Freight Partly on the Siding – Several Cars Demolished."[7]

A Jackson, Mississippi, newspaper report described the accident:

The south-bound passenger train No. 1 was running under a full head of steam when it crashed into the rear end of a caboose and three freight cars which were standing on the main track, the other portion of the train being on a sidetrack. The caboose and two of the cars were smashed to pieces, the engine left the rails and plowed into an embankment, where it overturned and was completely wrecked, the baggage and mail coaches also being thrown from the track and badly damaged. The engineer was killed outright by the concussion. His body was found lying under the cab, with his skull crushed and right arm torn from its socket. The fireman jumped just in time to save his life. The express messenger was thrown against the side of the car, having two of his ribs broken by the blow, but his condition is not considered dangerous.[8]

Jones's legend was quickly fueled by headlines such as "DEAD UNDER HIS CAB: THE SAD END OF ENGINEER CASEY JONES," The Commercial Appeal, Memphis, Tennessee; and "HEROIC ENGINEER – Sticks to his post at cost of life. Railroad Wreck at Vaughan's on Illinois Central Railroad – Terrible Fatality Prevented by Engineer's Loyalty to Duty – A passenger's Story," The Times-Democrat, New Orleans.[8]

The passenger in the article was Adam Hauser, formerly a member of The Times-Democrat telegraph staff. He was in a sleeper on Jones's southbound fast mail and said after the wreck:

The passengers did not suffer, and there was no panic.

I was jarred a little in my bunk, but when fairly awake the train was stopped and everything was still.

Engineer Jones did a wonderful as well as a heroic piece of work, at the cost of his life.

The marvel and mystery is how Engineer Jones stopped that train. The railroad men themselves wondered at it and of course the uninitiated could not do less. But stop it he did. In a way that showed his complete mastery of his engine, as well as his sublime heroism. I imagine that the Vaughan wreck will be talked about in roundhouses, lunchrooms and cabooses for the next six months, not alone on the Illinois Central, but many other roads in Mississippi and Louisiana.[8]

Illinois Central Railroad report on accident

[edit]

A conductor's report filed five hours after the accident stated, "Engineer on No.1 failed to answer flagman who was out proper distance. It is supposed he did not see the flag." This was the position the IC held in its official reports.[7]

The final IC accident report was released July 13, 1900, by A.S. Sullivan, general superintendent of IC. It stated, "Engineer Jones was solely responsible having disregarded the signals given by Flagman Newberry." John M. Newberry was the flagman on the southbound No. 83 that Jones hit. According to the report, he had gone out a distance of 3,000 feet (910 m), where he had placed warning torpedoes on the rail. He continued north a further distance of 500 to 800 feet (150 to 240 m), where he stood and gave signals to Jones's train No. 1. Historians and the press had questions about the official findings.

In the report, Fireman Sim Webb states that he heard the torpedo explode before going to the gangway on the engineer's side and seeing the flagman with the red and white lights standing alongside the tracks. Going to the fireman's side, he saw the markers of No. 83's caboose and yelled to Jones. But it would have been impossible for him to have seen the flagman if the flagman had been positioned 500–800 feet (150–240 m) before the torpedoes, as the report says he was. In any event, some railroad historians[who?] have disputed the official account over the years, finding it difficult if not impossible to believe that an engineer of Jones's experience would have ignored a flagman and fusees (flares) and torpedoes exploded on the rail to alert him to danger.

Contrary to what the report claimed, shortly after the accident and until his death Webb maintained, "We saw no flagman or fusees, we heard no torpedoes. Without any warning we plowed into that caboose."[7][8]

Injuries and losses from wreck

[edit]The personal injury and physical damage costs of the wreck were initially estimated as follows:

- Simeon T. Webb, Fireman Train No. 1, body bruises from jumping off Engine 382 – $5.00 (equivalent to $183 in 2023)

- Mrs. W. E. Breaux, passenger, 1472 Rocheblave Street, New Orleans, slight bruises – Not settled

- Mrs. Wm. Deto, passenger, No 25 East 33rd Street, Chicago, slight bruises left knee and left hand – Not settled

- Wm. Miller, Express Messenger, injuries to back and left side, apparently slight – $23.00 ($916 in 2023)

- W. L. Whiteside, Postal Clerk, jarred – $1.00 ($37 in 2023)

- R. A. Ford, Postal Clerk, jarred – $1.00 ($37 in 2023)

- Engine No. 382; $1,396.25 ($51,136 in 2023)

- Mail car No. 51 – $610.00 ($22,341 in 2023)

- Baggage car No. 217 – $105.00 ($3,846 in 2023)

- Caboose No. 98119 – $430.00 ($15,748 in 2023)

- IC box car 11380 – $4000.00 ($146,496 in 2023)

- IC box car 24116 – $55.00 ($2,014 in 2023)

- Total (property damage only) – $2,996.00 ($109,726 in 2023)[8]

An update indicated an additional $327.50 in property damage ($102.50 in track damage, $100.00 for freight, and $125.00 in wrecking expense) plus a settlement of $1.00 to Mrs. Breaux for her injuries. Mrs. Deto was identified as the spouse of an IC engineer, and in the update her claim for injuries was still unsettled.[8] There are no clearly authentic photographs of the famous wreck in existence.[8]

There has been some controversy about exactly how Jones died. Massena Jones, (former postmaster of Vaughan and director of the now-closed museum there), said "When they found Jones, according to Uncle Will Madison (a section hand who helped remove Jones's body from the wreckage), he had a splinter of wood driven through his head. Now this is contrary to most of the stories, some of which say he had a bolt through his neck, some say he was crushed, some say he was scalded to death."[7]

Later history of engines

[edit]For at least ten years after the wreck, the imprint of Jones's engine was clearly visible in the embankment on the east side of the tracks about two-tenths of a mile north of Tucker's Creek, which is where the marker was located. The imprint of the headlight, boiler, and the spokes of the wheels could be seen and people would ride up on handcars to view the traces of the famous wreck. Corn that was scattered by the wreck grew for years afterward in the surrounding fields.[11]

The wrecked 382 was brought to the Water Valley shop and rebuilt "just as it had come from the Rogers Locomotive Works in 1898," according to Bruce Gurner. It was soon back in service on the same run with Engineer Harry A. "Dad" Norton in charge—but bad luck seemed to follow it. During its 37 years of service, "Ole 382" was involved in accidents that took six lives before it was retired in July 1935. During its career, the 382 was renumbered 212, 2012, and 5012.[8]

In January 1903, criminal train wreckers caused 382 to wreck, nearly demolishing the locomotive. Norton's legs were broken and he was badly scalded. His fireman died three days later.

In September 1905, Norton and the 382 turned over in the Memphis South Yards. This time, however, the train was moving slowly and Norton was uninjured.

On January 22, 1912, 382 (now numbered 2012) was involved in a wreck that killed four prominent railroad men and injured several others. It is called the Kinmundy Wreck[12] as it happened near Kinmundy, Illinois. An engineer by the name of Strude was driving.[8]

Jones's beloved Engine No. 638 was sold to the Mexican government in 1921 and still ran there in the 1940s.[8]

Other people involved

[edit]Jones's African-American fireman Simeon T. Webb (born May 12, 1874), died in Memphis on July 13, 1957,[13] at age 83.

Jones's widow, Janie Brady Jones (born October 29, 1866), died on November 21, 1958, in Jackson at age 92.[14] At the time of Jones' death at age 37, his son Charles was 12, his daughter Helen was 10 and his youngest son John Lloyd (known as "Casey Junior") was 4.

Jones's wife received $3,000 in insurance payments (Jones was a member of two unions, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, and had a $1,500 policy with each union), and later settled with IC for an additional $2,650 (Earl Brewer, a Water Valley attorney who would later serve as Governor of Mississippi, represented her in the settlement).[8] Other than these payments, Mrs. Jones received nothing as a result of the wreck or Jones's service with the railroad, as the Railroad Retirement Fund was not established until 1937.

Jones's wife said she never had any thought of remarrying.[15] She wore black nearly every day for the rest of her life.[7]

Jones's tombstone in Jackson's Mount Calvary Cemetery gives his birth year as 1864, but according to information his mother wrote in the family Bible, he was born in 1863. The tombstone was donated in 1947 by two out-of-town railroad enthusiasts who accidentally got his birth year wrong. Until then, a simple wooden cross had marked his grave.[7]

Casey Jones references in music

[edit]Casey Jones's fame is largely attributed to the traditional song, “The Ballad of Casey Jones”,[7][16] also known as "Casey Jones, the Brave Engineer", recorded by, among others, Billy Murray, Mississippi John Hurt, Harry McClintock,[17] Furry Lewis, Johnny Cash, Ed McCurdy, and played live by the Grateful Dead, as well as Jones' friend Wallace Saunders, an African-American engine wiper for the IC.

Songs titled “Casey Jones”, usually about the crash or the engineer, have been recorded by Vernon Dalhart (Edison Disc recorded June 16, 1925), This Bike Is a Pipe Bomb, Feverfew (Blueboy (band)), Tom Russell, The New Christy Minstrels, Skillet Lickers, and the Grateful Dead.

IWW activist Joe Hill wrote and sang a protest song parody of "The Ballad of Casey Jones". ″Casey Jones—the Union Scab″ fictitiously portrays Jones as a strikebreaker at Southern Pacific. As his engine is badly in disrepair he crashes from a bridge, dies and goes to Heaven. There St. Peter wants him to break a strike of celestial musicians. The rebellious musicians form a local union and throw Casey down into Hell, where Satan urges him to shovel sulphur in the furnaces. Hill's version of the song was later performed and recorded by Utah Phillips, Pete Seeger, in Russian by Leonid Utyosov, and Hungarian by the Szirt Együttes. The historic figure Casey Jones was a dues-paying member of two unions.[18]

Songs about or related to Jones or the crash include:

- "Casey's Last Ride" – Kris Kristofferson

- "J C Cohen" a parody by Allan Sherman

- "Casey Jones" – Johnny Cash

- “Casey Jones” – Elizabeth Cotten

- "Do The Paranoid Style" – Bad Religion

- "Casey Jones" – Grateful Dead

- "Talking Casey" – Mississippi John Hurt

- "To the Dogs or Whoever" – Josh Ritter from The Historical Conquests of Josh Ritter

- "April the 14th Part 1" and "Ruination Day Part 2" – Gillian Welch from Time (The Revelator) — Casey Jones becomes a simile for another great collision, that of the RMS Titanic, on April 14, 1912.

- "St Luke's Summer" – Thea Gilmore from Rules For Jokers

- "KC Jones" – North Mississippi Allstars

- "Ridin' With the Driver" – Motörhead

- "Casey Jones Was His Name" – Hank Snow

- "Freight Train Boogie" – Marty Stuart

- "Knocking Down Casey Jones" – Wilmer Watts

- "What's Next to the Moon" – AC/DC

- “Casey Jones—the Union Scab” – Joe Hill

- "Casey Jones" – Gibson Bros. from "Big Pine Boogie"

- "Casey Jones" – This Bike is a Pipe Bomb

- "Casey Jones" – The Black

- "Casey Jones" – Claudia Lennear

- "Casey Jones" – Furry Lewis

- "The Ballad of Casey Jones" – Band of Annuals

- "Grist for the Malady Mill" – mewithoutYou

- "What Have They Done To The Trains" – Roy Acuff

- "Statecny Strojvudce" – Ladislav Vodicka

- "Strojvudce Prihoda" – Jiri Voskovec and Jan Werich

- "Casey Caught the Cannonball" – Jimbo Mathus

- "Casey's Crazy Train" – DNatureofDTrain

- In the lyrics of their 1964 recording of Wabash Cannonball (found on the album Connie Francis and Hank Williams Jr. Sing Great Country Favorites), Connie Francis and Hank Williams Jr. make reference to Jones: "We'll drink a toast to Casey Jones, may his name forever stand".

Casey Jones media references

[edit]- A 1927 movie, Casey Jones (1927), starred Ralph Lewis as Casey Jones, Kate Price as his wife, and a young Jason Robards Sr. as Casey Jones, Jr.

- The Return of Casey Jones was released by Monogram Pictures in 1933. The movie was based upon the novelette written by John Johns, a real New York Central conductor, originally published in the April 1933 issue of Railroad Stories Magazine. The story was reprinted by Bold Venture Press in 2019 in Railroad Stories #7, collecting other stories by John Johns.

- In his 1975 painting "Sources of Country Music", Thomas Hart Benton chose Casey Jones' fateful Engine No. 382, the "Cannonball", to represent the influence of railroads on Country Music.[19]

- A 1938 dramatic play by Robert Ardrey called Casey Jones stars a 1930s version of the hero. It was produced on Broadway with a critically heralded locomotive set-piece by Mordecai Gorelik.

- In the 1941 Walt Disney movie, Dumbo, a song refers to the engine of the circus train as 'Casey Junior' early in the film. This inspired the Casey Jr. Circus Train attractions found at both Disneyland Park in Anaheim and Disneyland Park in Paris and the Casey Jr. Splash 'n' Soak Station at the Magic Kingdom.

- In 1950, the Disney studio produced an animated cartoon short based on Casey Jones, entitled The Brave Engineer.

- From 1954 until 1973, Roger Awsumb played Casey Jones on Lunch With Casey in the Minneapolis/St. Paul market on WTCN-TV.

- The 1956 James Bond novel Diamonds Are Forever references Casey Jones during a train chase.

- Airing in 1958, Casey Jones was a television series loosely based on Jones's legend. It starred Alan Hale, Jr. as Casey Jones; Hale would later become well remembered for his role as "The Skipper" on the TV series Gilligan's Island. The series only ran for one season, with a total of 32 episodes. Its co-star was Dub Taylor.

- Beginning in 1950, Good & Plenty candy began an advertising campaign featuring a cartoon character named "Choo-Choo Charlie," a child railroad engineer who appeared in ads featuring a jingle based on "The Ballad of Casey Jones".

- In an episode of Captain Caveman and the Teen Angels titled "The Legend of Devil's Run", the villain's name is Casey Jones.

- Sesame Street: "The Ballad Of Casey Macphee" casts the Cookie Monster as an engine driver faced with his train loaded with cookies, chocolate, milk and cows trapped by an avalanche, but while tempted to consume the food bravely chooses to "eat the snow instead".

- The 1982 film An Officer and a Gentleman features a coarse cadence call about "Casey Jones", led by Gunnery Sgt. Foley (Louis Gossett Jr.). It carried over into the real military, until it was outlawed under the regulations regarding sexual harassment.

- Casey Jones is mentioned in Caryl Phillips's stageplay The Shelter (1984).

- Casey Jones is the vigilante comrade of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

- An episode of The Real Ghostbusters (titled Last Train To Oblivion) (1987) features the ghost of Casey Jones. He abducts Peter Venkman, and always yells at him for more coal. Peter eventually realizes that Jones wants to repeat the journey that killed him, so that he can avoid the collision this time.

- Neil Young's song "Southern Pacific" alludes to the Casey Jones legend by imagining a railroad engineer named "Mr. Jones" who meets a less heroic but in some ways a more tragic fate: when he turns 65 years old, he is compelled into retirement by the railroad company as "company policy."

- Tommy Lee Jones' character in the film The Fugitive mentions Casey Jones after the initial train crash of the movie.

- A 1993 episode of Shining Time Station called "Billy's Runaway Train", includes a play about Casey Jones.

- In a 1996 The Simpsons episode, "Burns, Baby Burns", guest star Rodney Dangerfield voices a character that chases after a train and calls out to the conductor by referring to him as Casey Jones.

- In 1997, The Green Bag published a poem by Brainerd Currie, Casey Jones Redivivus, about a man injured in a railroad accident.[20]

Museums in Casey Jones's honor

[edit]- The Historic Casey Jones Home & Railroad Museum in Jackson, Tennessee

- Water Valley Casey Jones Railroad Museum in Water Valley, Mississippi

- Casey Jones Railroad Museum State Park in Vaughan, Mississippi (Museum closed in 2004)[21]

References

[edit]- ^ "AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame: Erwin 'Cannonball' Baker". Motorcycle Hall of Fame. Pickerington, OH USA: American Motorcyclist Association. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "Facts About Casey Jones". CaseyJones.com. Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ "Casey Jones". biography.com. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Erie Railroad Magazine Vol 24 (April 1928), No 2, pp. 13,44.

- ^ Lee, Fred J. (2008). Casey Jones: Epic of the American Railroad. Lee Press. ISBN 9781443728928.

- ^ "Casey Jones' Whistler Museum And Park – Hon. Sonny Callahan (Extension of Remarks – October 14, 1993)". Congressional record. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The Historic Casey Jones Home & Railroad Museum in Jackson, Tennessee". Archived from the original on May 28, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Water Valley Casey Jones Railroad Museum in Water Valley, Mississippi". Archived from the original on March 14, 2008.

- ^ Hubbard, Freeman H. (1945). Railroad Avenue, p. 12 McGraw Hill, New York

- ^ Lee, Fred J. (1939). Casey Jones, p.260, Kingsport, Tennessee: Southern Publishers

- ^ Jones, Massena F. (1978) The Choo-Choo Stopped at Vaughan. Quail Ridge Press.

- ^ "Train Wreck". Kinmundy Historical Society. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ "Poplar Ave. Station". condrenrails.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ "Death Comes at 92 to Casey Jones's Widow". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. November 22, 1958. p. 14.

- ^ "Widow of Casey Jones Is Dead at 92: "Haunted" by Ballad of Famed Engineer". The New York Times. November 22, 1958. p. 21.

- ^ Lomax, John A and Lomax, Alan. (1934) American Ballads and Folk Songs. Macmillan., p. 34.

- ^ "Casey Jones (The Union Scab) – YouTube". YouTube. 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Water Valley Casey Jones Railroad Museum in Water Valley, Mississippi". Archived from the original on November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Thomas Hart Benton". Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ Brainerd Currie. "Casey Jones Redivivus" (PDF). The Green Bag. Retrieved 2018-06-29.

- ^ "Abandoned: Vaughan, Mississippi". Preservation in Mississippi. March 7, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- A History of Railroad Accidents, Safety Precautions and Operating Practices, by Robert B. Shaw. p290. (1978)