Charles Graner | |

|---|---|

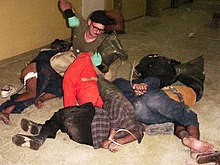

Graner posing over the body of Manadel al-Jamadi, an Iraqi prisoner who was tortured to death during interrogation in Abu Ghraib prison in November 2003 | |

| Born | Charles A. Graner Jr. November 10, 1968 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Occupation | Soldier (formerly) |

| Criminal status | Released |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4 |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Criminal penalty | 10 years imprisonment plus a dishonorable discharge |

| Accomplice(s) | Lynndie England |

| Imprisoned at | United States Disciplinary Barracks (released in August 2011) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | c. 1988 – c. 1992 2001–2005 |

| Rank | Private (formerly Specialist) |

| Unit | 372nd Military Police Company |

| Battles / wars | Gulf War Iraq War |

Charles A. Graner Jr. (born November 10, 1968) is an American former soldier and corrections officer who was court-martialed for prisoner abuse after the 2003–2004 Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal. Along with other soldiers of his Army Reserve unit, the 372nd Military Police Company, Graner was accused of allowing and inflicting sexual, physical, and psychological abuse on Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib prison, a notorious prison in Baghdad during the United States' occupation of Iraq.

On January 14, 2005, Graner was found guilty under the Uniform Code of Military Justice on charges of conspiracy to maltreat detainees, failing to protect detainees from abuse, cruelty, and maltreatment, as well as charges of assault, indecency, and dereliction of duty. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison, demotion to private, dishonorable discharge and forfeiture of pay and allowances. Charges of adultery and obstruction of justice were dropped before trial.[1] On August 6, 2011, Graner was released from the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, after serving 6+1⁄2 years of his ten-year sentence.[2]

Early life

[edit]Graner grew up in Baldwin, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh.[3] After graduating from high school in 1986, Graner attended the University of Pittsburgh for two years before dropping out to join the Marine Corps Reserve in April 1988. He had the Marine Corps emblem and the letters "USMC" tattooed on his upper right biceps.[4]

In 1990, Graner married Staci M. Dean, a 19-year-old from Ohiopyle, Pennsylvania. The couple had two children.[citation needed] Trained as a military policeman, he served in the Persian Gulf War in 1991. He was in the Marines until May 1996, when he left with the rank of lance corporal.[citation needed]

Graner was deployed during the Gulf War, serving with the 2nd MP Co, originally of 4th FSSG, 4th Marine Division, a Marine Reserve unit based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. On January 11, 1991, he arrived in Saudi Arabia, taking part in Operation Desert Storm. From there, he traveled to the largest prisoner-of-war camp near the Saudi-Kuwaiti border, where he worked for about six weeks.[citation needed]

Prison guard

[edit]After his marriage, he moved to Butler, Pennsylvania, a steel industry area in southwestern Pennsylvania. In 1994, he began working as a corrections officer at Fayette County Prison in a shift with a "no-nonsense reputation." Once, Graner was accused of putting mace in a new guard's coffee as a joke, causing him to be sick.[5]

In May 1996, he moved to the State Correctional Institution, Greene, a maximum-security prison in Greene County, Pennsylvania. Almost 70% of the inmates were black, many from large cities, but it was located in a rural part of the state and more than 90% of the guards were white.[6] Guards at the prison were accused of beating and sexually assaulting prisoners and conducting cavity searches in view of other prisoners. There were also reports of racism, including reports of guards writing "KKK" in the blood of a beaten prisoner. In 1998, two guards were fired and 20 others were suspended, demoted or reprimanded for prisoner abuse.[5][7]

In 1998, a prisoner accused Graner and three other guards of planting a razor blade in his food, causing his mouth to bleed when he ate it.[6] The prisoner accused the guards of first ignoring his cries for help and then punching and kicking him when they took him to the nurse. Graner was accused of telling him to "Shut up, nigger, before we kill you."[5] The allegations were denied; although a federal magistrate judge ruled that the charges had "arguable merit in fact and law," the case was dismissed when the prisoner disappeared after his release.[5] Graner and four other guards were accused of beating another prisoner who had deliberately flooded his cell, taunting anti-capital punishment protesters, using racial epithets and telling a Muslim inmate he had rubbed pork all over his tray of food.[5]

A second lawsuit involving Graner was brought by a prisoner who claimed that guards made him stand on one foot while they handcuffed and tripped him. This allegation was ruled to have been made too late under the statute of limitations.[3][6]

Domestic abuse

[edit]In May 1997, Graner's wife and mother of their two children filed for divorce and sought a protection order, saying Graner had threatened to kill her. A six-month order was granted, unopposed by Graner. Shortly after the first one expired, Staci Dean was granted a second protection order, saying Graner had come to her house, thrown her against some furniture, thrown her on the bed, grabbed her arm and hit her face with her arm. Three years later, Dean called police after Graner came to her house and attacked her. Dean said Graner had "yanked me out of bed by my hair, dragging me and all the covers into the hall and tried to throw me down the steps." Afterwards, Graner called a friend of Dean's and allegedly said, "I have nothing if she's not my wife, she's dead." Graner admitted the attack and a third order of protection was granted.[5]

Soon after, an order of protection was granted against Graner to protect his estranged wife. This resulted from Graner's comment to Dean that "she could keep his guns, because he did not need them for what he was going to do to the plaintiff."[8]

Abu Ghraib

[edit]

In November 2003, Graner was awarded a commendation from the Army for serving as an MP in Iraq.[3] Graner held the rank of specialist[9] in the company during his tour of duty in Iraq.

Allegations

[edit]

Thirteen prisoners were interviewed by military investigators after the abuse allegations emerged. Eight of them named Graner as one of the abusers, and the other five described a person fitting his description.[10] The investigation report named Graner as a ringleader of the abuse.[11]

One of the prisoners, Kasim Mehaddi Hilas, said that one day he asked Graner for the time so that he could pray. Graner handcuffed him to the bars of a cell window and left him there, feet dangling off the floor, for nearly five hours. On another occasion, Graner and other soldiers tied a prisoner to a bed and sodomized him with a phosphoric light while another soldier took photographs.[10]

Another prisoner, Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, said Graner forced him to stand on a food box, naked except for a blanket. Another soldier then put a bag over his head and electrodes on his fingers, toes and penis. The picture of this incident was one of the first pictures whose publication prompted the investigation.[10] A third prisoner, Mohanded Juma Juma, said Graner often threw food into the toilets and told the prisoners to eat it.[10]

Jeremy Sivits, a soldier who pleaded guilty to charges relating to the Abu Ghraib investigation, alleged that Graner once punched a prisoner in the head so hard that he lost consciousness.[11]

Timeline

[edit]

- 2002: Graner joins the Army Reserve.

- May 5, 2003: Graner called to active duty in Iraq.

- 2003–2004 Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse:

- Specialist Sabrina Harman testified as to Graner's assignment, "It is Graner and Frederick's job [...] to get these people to talk" for military intelligence officers and for 'OGA,' short for 'Other Government Agency,' a nickname for the CIA."[12]

- Graner appears in several pictures with his fellow guards Lynndie England and Sabrina Harman, giving the thumbs up in front of nude prisoners. In one photo, Graner poses over the dead body of Manadel al-Jamadi, an Iraqi prisoner; a small patch of blood can be seen on al-Jamadi's right temple and his eyes are sealed closed with tape. According to Spc. Jason Kenner's testimony, al-Jamadi was brought to the prison by Navy SEALs in good health; Kenner says he saw that al-Jamadi looked extensively bruised when he was brought out of the showers, dead. According to Kenner a "battle" took place among CIA and military interrogators over who should dispose of the body. Capt. Donald Reese, company commander of 372nd Military Police Company, gave testimony about al-Jamadi's death, saying he saw the dead prisoner. Reese testified, "I was told that when he was brought in, he was combative, that they took him up to the room and during the interrogation he passed."[13] Reese stated the corpse was locked in a shower room overnight, which is where he first saw him. Reese says he was first told the man had died of a heart attack, but when he saw him he "was bleeding from the head, nose, mouth".[13] The body was then autopsied, concluding that the cause of death was a blood clot from trauma.[13]

- Prisoner Kasim Mehaddi Hilas testifies regarding his experiences at Abu Ghraib, telling investigators that Graner had cuffed him to the bars of a cell window, after Hilas had asked Graner what time it was because he wanted to pray. Graner left him, feet dangling above the floor, for almost five hours.[10] Hilas also detailed events he had witnessed of Graner and some of his fellow soldiers sodomizing and otherwise abusing other detainees. These events were also detailed by other prisoners including some of the victims themselves. According to Hilas, Graner also "repeatedly threw the detainees' meals into the toilets and said, 'Eat it.'"[10]

- Spec. Joseph M. Darby, who reported what was happening in the prison, stated that he had asked Graner, when he was the MP in charge of the tier's night shift, "if he had any photographs of the cell where the shooting took place."[14] Darby received two CDs of photographs from Graner. Darby told investigators, "I thought the discs just had pictures of Iraq, the cell where the shooting occurred." However, the discs contained "hundreds of photographs showing naked detainees being abused by U.S. soldiers." Feeling that what he had seen was "just wrong", Darby was compelled to do something about it. Upon being confronted by Darby, Graner responded, "The Christian in me says it's wrong, but the corrections officer in me says, 'I love to make a grown man piss himself."[14]

- Julie Scelfo and Rod Nordland of Newsweek reported, "One military investigator wrote in his notes on Graner: 'the biggest S.O.B. on earth,' a comment he underlined twice."[15]

- May 14, 2004: U.S. Army files seven criminal charges against Graner under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, with punishments ranging up to 24½ years in prison, forfeiture of pay, reduction in rank and a dishonorable discharge:[16]

- Conspiracy to maltreat detainees;

- Dereliction of duty for willfully failing to protect detainees from abuse, cruelty and maltreatment;

- Assaulting detainees;

- Committing indecent acts;

- Adultery;

- Obstruction of justice;

- Maltreatment of detainees.

- The charges of adultery and obstruction of justice were dropped before the first trial began.[17] Later, other charges were dropped, leaving only the charges for conspiracy to maltreat detainees, assault and committing indecent acts. This made the maximum penalty 17½ years instead of 24½ years.[18]

- May 19, 2004: Graner is arraigned along with Staff Sergeant Ivan L. "Chip" Frederick II and Sergeant Javal Davis. All of them waive their right to have charges read aloud. Their pleas were deferred. On the same day, Jeremy C. Sivits, the first soldier to go on trial, is sentenced to the maximum penalty of one year in prison and a bad conduct discharge.[19]

- June 25, 2004: Spc. Israel Rivera, a military intelligence analyst, testifies at a hearing in Baghdad that will decide whether Spc. Sabrina Harman should be court-martialed. Rivera says Graner shouted "homosexual slurs" at three naked prisoners, "ordering them to crawl along the ground so their genitalia had to drag along the floor." According to Rivera, "Graner was shouting things like, 'Are you guys fucking in there' and 'fucking fags.'"[20]

- Three key witnesses refused to testify against Graner during a secret hearing on the grounds they might incriminate themselves (see Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution):[21]

- Lieutenant Colonel Steven L. Jordan, who as director of the Joint Interrogation and Debriefing Center at the prison oversaw the interrogations;

- Captain Donald J. Reese, who was commander of the 372nd Military Police Company, in which Graner served; and

- Adel Nakhla, civilian translator, employed by private military contractor Titan Corporation, assigned to the 205th Military Intelligence Brigade; mentioned in the Taguba Report as suspect.

Court-martial

[edit]Article 32 hearing

[edit]Due to security problems with holding pre-trial hearings in Baghdad, the case was transferred to Germany. On August 23, Graner appeared before military judge Colonel James Pohl at a high-security Army base in the city of Mannheim in southwest Germany. On that day, Article 32 hearings were held. These preliminary hearings usually function as an arraignment and allow the judge to hear and decide on motions made by the prosecutor and the defense. Graner appeared with Specialist Megan Ambuhl, along with his civilian attorneys and appointed military defense lawyers.[22]

During the Article 32 hearing, attorneys for Harman and Graner made discovery motions. Pohl set a deadline of September 10 for the government to provide the defense team with the documents requested, and ordered the release of a U.S. Army report performed by the Criminal Investigational Division on investigative procedures, as well as the Schlesinger panel report.[22]

Graner's attorney (as well as attorneys for several others charged) also moved to suppress evidence of statements made to Army investigators during interrogations, as well as seizure of a computer. Also requested was a change of venue, because some witnesses could not be compelled to come to Iraq to testify. In addition, the defense sought immunity from prosecution for several people so they may testify for the defense. The judge denied all three motions, and also ruled that video testimony and depositions could be used as evidence.[22]

October 22 hearing

[edit]Another pre-trial hearing was held on October 22, at Camp Victory in Baghdad, with Pohl again presiding as judge. Pohl set January 7, 2005, as the trial date and again denied a defense motion to grant immunity to several witnesses so they could testify without fear of incrimination.[23] On November 11, Lieutenant Colonel Fred Taylor, a judge advocate in the regional defense counsel's office at Camp Victory, notified Graner that the military judge ordered that all further hearings in the case would be held at Fort Hood, Texas.[24]

Not guilty plea and court-martial member selection

[edit]The trial officially began on January 7, at the Williams Judicial Center in Fort Hood, with Colonel James Pohl presiding. A ten-member, all-male court-martial was seated, consisting of four officers and six enlisted men—all of whom had served in either Iraq or Afghanistan. Under military law, three fourths of the members must vote guilty to convict a person of each charge.[25]

Graner entered a not-guilty plea to each of the five charges. Two officers detailed as members of the court were not seated—Colonel Allen Batschelet for saying he was embarrassed as an Army officer after seeing the photos and had strong views about the case, and Lieutenant Colonel Mark Kormos by the prosecutors for no reason given.[25]

During the session a list of potential witnesses was also made public. It included three other soldiers in Graner's unit from western Pennsylvania: Captain Donald Reese of New Stanton, Specialist Jeremy Sivits of Bedford County, and Sergeant Joseph Darby of Somerset County. Reese was the unit commander and had been reprimanded in connection with Abu Ghraib; Sivits had already pleaded guilty in a plea bargain; Darby was the soldier who first reported the situation at Abu Ghraib. At the hearing several other possible witnesses were listed, including the prerecorded video depositions of three Iraqi prisoners—two for the prosecution and one for the defense. Graner's lawyer, Guy Womack, said he was not sure whether Graner would testify for himself.[25]

After the hearing journalists interviewed Graner outside the courtroom, where Graner expressed a positive attitude, saying "Whatever happens here is going to happen. I still try to stay positive."[25][26]

Testimony

[edit]Opening statements began on January 10. During this hearing, witness testimony began. Three soldiers in Graner's unit testified; the first was Specialist Matthew Wisdom, who first reported the situation at Abu Ghraib. Wisdom said that Graner had enjoyed beating inmates (saying that he had laughed, whistled, and sung) and was the one who first thought of arranging the prisoners in naked human pyramids and other positions.[27] On this day the Military Judge, Michael Hunter, banned any further reporting of the hearing.[28]

Testimony continued the next day, as Syrian foreign fighter Ameed al-Sheikh told the court in video testimony that Graner had beaten him while he was recovering from a bullet wound. Al-Sheikh described Graner as the "primary torturer" and said that he had forced him to eat pork, drink alcohol,[29] and thank Jesus for keeping him alive.[30] Another detainee, Hussein Mutar, testified that Graner had forced him, like al-Sheikh, to eat pork, drink alcohol, and curse Islam. He was also forced to masturbate in public and was one of the men stacked into a pyramid naked.[29]

On January 11, military prosecutors also presented evidence not publicly released, including a video of forced group masturbation and a picture of a female prisoner being forced to show her breasts.[15]

Following orders

[edit]The main defense was that Graner was following orders from, and supervised by, intelligence officers.[31] Graner and others testified that many senior officers were aware of the activities and actively supported them. This is why he was not worried about taking and distributing the photographs which were later used against him. Referring to military intelligence, Graner testified "I nearly beat an MI detainee to death with MI there" before Pohl cut him off.[32]

A formal complaint about the abuse was filed by Specialist Matthew Wisdom in November 2003 but was ignored by the military. Private Ivan Frederick (previously convicted of abuse) said he had consulted six senior officers, ranging from captains to lieutenant-colonels, about the guards' actions but was never told to stop. Despite this, the prosecution did not call any senior officers to testify. Womack suggests that this was not because they "just forgot" to do so.[33]

White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales had issued a memo which defined torture very narrowly as "intentionally causing permanent damage to vital organs or permanent emotional trauma".[34] This would have excluded Graner's acts of intimidation. However the prosecution argued that even if he was following orders from senior officers, he should have known that the orders were illegal.[35]

Verdict

[edit]On January 15, 2005, Graner was found guilty of assault, battery, conspiracy, maltreatment of detainees, committing indecent acts and dereliction of duty and sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment, reduction in rank to private, a dishonorable discharge, and the loss of all pay and benefits.[36]

Defense lawyer Guy Womack contended that Graner and the six other Abu Ghraib guards charged with abuses were being scapegoated.[36] For example, The Washington Post reported in 2004 that a torture position known as a "Palestinian hanging", where a prisoner is suspended by their hands behind their back, was approved by the Bush administration for use in CIA interrogations (termed an "enhanced interrogation technique" by the CIA).[37]

Graner's mother, Irma Graner said, "You know it's the higher-ups that should be on trial ... they let the little guys take the fall for them. But the truth will come out eventually."[38]

Life post-trial

[edit]Graner was imprisoned in the United States Disciplinary Barracks in Leavenworth, Kansas.[39]

In 2005, while serving time for his role in the Abu Ghraib scandal, Graner married fellow Abu Ghraib guard Megan Ambuhl. Graner was in a relationship with fellow soldier, Lynndie England, and they had a child.[40] Ambuhl was not permitted to see him for the first 2½ years of his incarceration; it was a proxy wedding with a friend.[25] Ambuhl previously pleaded guilty to two minor charges but served no jail time and was discharged.

Graner was released from prison after serving 6+1⁄2 years of a ten-year sentence. He remained on parole until December 25, 2014.[41]

Graner and his wife have declined interview requests.[42]

See also

[edit]- Standard Operating Procedure (film) – 2008 documentary film by Errol Morris

References

[edit]- ^ Abu Ghraib Court Martial: "Ring Leader" Spc. Charles A. Graner Jr. Sentenced to Ten Years Archived 2008-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Defense Information. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ Dishneau, David. Key figure in Abu Ghraib abuse freed from prison[dead link], Associated Press, August 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c Guard Left Troubled Life for Duty in Iraq, The New York Times, 2004-05-14. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Fuoco, Michael A., et al. (2004-05-08)"Suspect in prisoner abuse has a history of troubles" Post-Gazette.com. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Records Paint Dark Portrait Of Guard, The Washington Post, 2004-06-05. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ a b c Unveiling the Face of the Prison Scandal, Los Angeles Times, 2004-06-19. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ MP investigated in Iraq was at Pa. prison during abuse scandal, but not implicated Archived 2004-06-08 at the Wayback Machine, The San Diego Union-Tribune, 2004-05-07. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Abuse scandal meets disbelief in hometowns. USA Today, 2004-05-06. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ "Preferred Charges Against Spc. Charles Graner (May 14, 2004)". News.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ a b c d e f New Details of Prison Abuse Emerge, The Washington Post, 2004-05-21. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ a b 3 to Be Arraigned in Prison Abuse[dead link], The Washington Post, 2004-05-19. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ "CBSNews.com Who's Who Person". www.cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2004.

- ^ a b c "ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". www.abc.net.au. 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ a b Punishment and Amusement, The Washington Post, 2004-05-21. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ a b Beneath the Hoods Archived February 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Los Angeles Times] Iraq Prison Case Attorney a Military Law Expert[dead link], Los Angeles Times, 2004-05-15. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Preferred Charges Against, findlaw.com, 2005-05-14. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Defense Witness: Graner Disobeyed Orders, NBC Austin, 2005-01-12. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Soldier Sentenced to One-Year Confinement for Prison Actions Archived September 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, italy.usembassy.gov, 2004-05-19. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Zimbardo, Philip (2008-01-22). The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8129-7444-7.

- ^ Serrano, Richard A. "3 witnesses in abuse case aren't talking / Higher-ups and a contractor out to avoid self-incrimination". SFGATE. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ a b c Abu Ghraib Article 39A Hearings Held in Germany, U.S. Department of Defense, defenselink.mil. Retrieved 2009-03-05. Archived 2009-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Panel for Detainees' Cases Cut in Half (washingtonpost.com)". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ THE CONFLICT IN IRAQ: MILITARY JUSTICE; Trials of G.I.'s At Abu Ghraib To Be Moved To the U.S., The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e Court-Martial Will Hear Taped Testimony of Prisoners, The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ "CNN.com - Transcripts". transcripts.cnn.com. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Behind Failed Abu Ghraib Plea, a Tangle of Bonds and Betrayals, The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ Torture? Not if cheerleaders do it, lawyer claims[dead link], The Times Online. Retrieved 2009-03-05.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Abu Ghraib inmates recall torture". 2005-01-12. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ THE REACH OF WAR: DETAINEES; Testimony From Abu Ghraib Prisoners Describes a Center of Violence and Fear, The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ Prosecuting Abuse Archived 2014-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, 2004-05-10. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Badger, T.A (28 September 2005). "Lynndie England sentenced to three years for Abu Ghraib abuses". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Guard Convicted In the First Trial From Abu Ghraib, The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ "Gonzales OK could be seen as OK for torture rules" (PDF). kuwaitfreedom.org. 2 February 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ Soldiers Testify on Orders To Soften Prisoners in Iraq, The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ a b "Graner gets 10 years for Abu Ghraib abuse". NBC News. 2005-01-06. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "Torture, American-Style". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "The Australian: Son the fall guy for abuse: mum [January 16, 2005]". 2005-03-13. Archived from the original on 2005-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "Notorious Abu Ghraib guard released from prison". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "Lynndie England gives birth in US". 13 October 2004.

- ^ Dishneau, David, (Associated Press), "Abu Ghraib Abuse Ringleader Freed Early From Military Prison", The Boston Globe, 7 August 2011.

- ^ Dishneau, David, Key Figure in Abu Ghraib Abuse Freed From Prison, San Francisco Chronicle, August 6, 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Badger, T.A. "Jury seated in Graner prisoner abuse case[permanent dead link]." Associated Press. January 7, 2005.

- Cauchon, Dennis. "Lawyer wants Rumsfeld to testify in prison-abuse case." USA Today: June 13, 2003.

- Fuoco, Michael A., et al. "Suspect in prisoner abuse has a history of troubles." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: May 8, 2004.

- Lieberman, Paul, and Dan Morain. "Unveiling the Face of the Prison Scandal[dead link]." Los Angeles Times: June 19, 2004.

- Lin, Judy. "Soldier target of prior abuse allegations." Associated Press: May 13, 2004.

- Peirce, Paul. "Graner remains positive before trial." Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. January 8, 2005.

- Serrano, Richard A., and Greg Miller. "Prison intelligence officers scrutinized." The Los Angeles Times: May 23, 2004.

External links

[edit] Media related to Charles Graner at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles Graner at Wikimedia Commons