| Chilote Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Chilote, castellano chilote | |

| Pronunciation | [tʃiˈlote], [kasteˈʝano tʃiˈlote] |

| Native to | Chiloé Archipelago, Chile and vicinity. |

| Ethnicity | Chilote Chileans |

Early forms | |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Chilote is a dialect of Spanish language spoken on the southern Chilean islands of Chiloé Archipelago (Spanish: Archipiélago de Chiloé or simply, Chiloé). It has distinct differences from standard Chilean Spanish in accent, pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary, especially by influences from local dialect of Mapuche language (called huilliche or veliche) and some conservative traits.

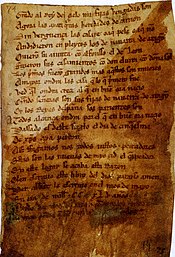

After the battle of Curalaba (1598) and the Destruction of the Seven Cities Chiloé was further isolated from the rest of Chile and developed a culture with little influence from Spain or mainland Chile. During the 17th and 18th centuries most of the archipelago's population was bilingual and according to John Byron many Spaniards preferred to use Mapudungun because they considered it more beautiful.[1] Around the same time, Governor Narciso de Santa María complained that Spanish settlers in the islands could not speak Spanish properly, but could speak Veliche, and that this second language was more used.[2]

Phonology

[edit]- As in Chilean Spanish, the /s/ is aspirated at the end of the syllable and the /d/ between vowels tends to be removed.

- Aspirated realization of "j" as [h].

- Transformation of the groups [bo, bu] and [ɡo, ɡu] into [wo, wu].

- Preservation of the nasal consonant velar /ŋ/ (written "ng" or "gn") in words of Mapuche origin. This phoneme does not exist in standard Spanish. Eg: culenges [kuˈleŋeh] (In the rest of Chile, it is said culengues [kuˈleŋɡeh]).

- Difference in treatment for "y" and "ll" : From Castro to the north, no difference is made between them, since both are pronounced as [ʝ] (yeísmo). In sectors of the center and the south they are pronounced differently, they can be [ʝ] and [dʒ], [ʝ] and [ʒ] or [dʒ] and [ʒ]. There are also other places in the southern and western parts where they are both pronounced [ʒ].

- It is common for "ch" to be pronounced as a fricative [ʃ], similar to an English "sh". This fricative pronunciation has a social stigma associated in Chile.

- In some places the group "tr" is pronounced differently according to the etymology of the word: if it comes from Spanish, both consonants are clearly pronounced, while if the word comes from Mapudungun, it is pronounced [tɹ], similar to a "chr". However, in the rest of the places, the words of Mapuche origin that had this consonant have replaced it by the "chr" and in the rest this group is pronounced [tɾ] as in most dialects of Spanish, unlike what occurs in Chilean Spanish, in which you tend to use [tɹ] regardless of the origin of the word.

- Paragoge: A vowel is added to the end of words ending in "r" or "c". Eg: andar [anˈdarə], Quenac [keˈnakə].

- The prosodic aspects of Chiloé Spanish have recently been studied and show an ascending intonation.

Morphology

[edit]The Spanish of the Chiloé Archipelago shares a number of morphological characteristics with that of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado and with that of rural areas of the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Durango, Sonora, Tlaxcala, Jalisco, and Guanajuato:[3]

- Second-person preterite forms ending in -ates, -ites instead of the standard -aste, -iste.

- Latin -b- is retained in some imperfect conjugations of -er and -ir verbs, with the preceding -i- diphthongized into the previous vowel, as in: caiban vs. caían, traiba vs. traía, creiban vs creían.

- Verbs ending in -er are, like those ending in -ir, conjugated in -imos for both the present and preterite tenses. The reverse occurs in New Mexico and rural Mexico, where -ir verbs can be conjugated -emos in the present tense.

- Non-standard -g- in many verb roots, such as creiga 'believe'.

- In their present-tense subjunctive first person plural conjugations, verbs are pronounced with stress on the antepenultimate syllable, instead of on the penultimate one, thus váyamos and báilemos instead of vayamos and bailemos.

- The clitic pronoun nos 'we' is often replaced by los. This is found in Traditional New Mexican Spanish but is not attested within Mexico.

References

[edit]- ^ Byron, John. El naufragio de la fragata "Wager". 1955. Santiago: Zig-zag.

- ^ Cárdenas, Renato; Montiel, Dante y Hall, Catherine. Los chono y los veliche de Chiloé. 1991 Santiago: Olimpho. p. 277 p

- ^ Sanz, Israel; Villa, Daniel J. (2011). "The Genesis of Traditional New Mexican Spanish: The Emergence of a Unique Dialect in the Americas". Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. 4 (2): 417–442. doi:10.1515/shll-2011-1107. S2CID 163620325. Retrieved 13 April 2021.