This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

Cisalpine Republic Repubblica Cisalpina (Italian) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1797–1802 | |||||||||||||||||

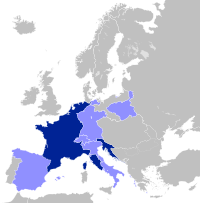

The Cisalpine Republic in 1797 | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Sister Republic of France | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Milan | ||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Italian | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary directorial republic | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council | ||||||||||||||||

| Council of Elders | |||||||||||||||||

| Council of Juniors | |||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | French Revolutionary Wars | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 April 1797 | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 29 June 1797 | ||||||||||||||||

• Constitution adopted | 8 July 1797 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17 October 1797 | |||||||||||||||||

• Golpe and second Constitution | 31 August 1798 | ||||||||||||||||

| 27 April 1799 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 June 1800 | |||||||||||||||||

| 26 January 1802 | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 1797 | 42,500[1] km2 (16,400 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1797 | 3,240,000[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Milanese scudo, lira, soldo and denaro | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Cisalpine Republic (Italian: Repubblica Cisalpina; Lombard: Republica Cisalpina) was a sister republic or a client state of France in Northern Italy that existed from 1797 to 1799, with a second version until 1802.

Creation

[edit]After the Battle of Lodi in May 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte organized two states: one to the south of the Po, the Cispadane Republic, and one to the north, the Transpadane Republic. On 19 May 1797, Napoleon transferred the territories of the former Duchy of Modena to Transpadania and, on 12 Messidor (29 June), he decreed the birth of the Cisalpine Republic, creating a Directory for the republic and appointing its ministers. France published the constitution of the new republic on 20 Messidor (7 July), establishing the division of the territory into eleven departments: Adda (Lodi), Alpi Apuane (Massa), Crostolo (Reggio), Lario (Como), Montagna (Lecco), Olona (Milan), Panaro (Modena), Po (Cremona), Serio (Bergamo), Ticino (Pavia), and Verbano (Varese).

The rest of Cispadania was merged into the Cisalpine Republic on 27 July, with the capital of the unified state being Milan. On 1 Brumaire (22 October), Bonaparte announced the union of Valtelline with the Republic, after its secession from the Swiss Three Grey Leagues. Austria acknowledged the new entity in the Treaty of Campoformio of 17 October, gaining in exchange what remained of the Venetian Republic. On 25 Brumaire (15 November), the full international recognition and legality of the new state was ratified by the law governing the final annexation of the conquered territories.

The parliament, composed of two chambers (the Great Council and the Council of the Seniors), was appointed directly by Napoleon on 1 Frimaire (21 November). He justified this undemocratic action as a necessity of war. New departments joined the eleven original ones and Valtelline in the following months: Benaco (Desenzano) on 11 Ventose (1 March 1798), Mella (Brescia) on 13 Floreal (2 May), Mincio (Mantua) on 7 Prairial (26 May), and five departments of Emilia. The structural phase of the republic was terminated on 14 Fructidor (31 August), when France dismissed all the authorities of the republic, replacing them with a stronger executive power under a new constitution.

Government

[edit]First constitution

[edit]The Cisalpine Republic was for many years under the dominion of the House of Austria.

The French Republic succeeded it by right of conquest. It now renounces this right, and the Cisalpine Republic is free and independent. Recognized by France and by the Emperor, it will soon be equally acknowledged by the rest of Europe.

The Executive Directory of the French Republic, not content with employing its influence, and the victories of the Republican armies, to secure the political existence of the Cisalpine Republic, extends its care still further; and convinced that, if liberty be the first of blessings, the revolution which attends it is the greatest of evils, it has given to the Cisalpine people their peculiar Constitution, resulting from the wisdom of the most enlightened nation.

From a military regime, the Cisalpine people pass to a constitutional one.

That this transition should experience no shock, nor be exposed to anarchy, the Executive Directory thought proper to nominate, for the present, the members of the government and the legislative body, so that the people should, after the lapse of one year, have the election to the vacant places, in conformity to the Constitution.

For a great number of years, there existed no republic in Italy. The sacred fire of liberty was extinguished, and the finest part of Europe was under the yoke of strangers. It belongs to the Cisalpine Republic to show to the world by its wisdom, its energy, and the good organization of its armies, that modern Italy is not degenerated, and is still worthy of liberty.

(Signed) Buonaparte.

— Proclamation of General Buonaparte (later became the Preamble to the Constitution of the Cisalpine Republic), Montebello, 11 Messidor, year V (29 June 1797).[2]

The institutions of the Cisalpine Republic were very similar to those of France. Its first constitution, adopted on 8 July 1797, was based on the French Constitution of 1795.[1] A five-member directory constituted the executive branch of government.[1] The territory was divided into departments[1] which elected the judges of peace, the magistrates and the electors, one for every 200 people having the right to vote. The latter elected two councils: the Consiglio dei Seniori ("Council of the Seniors") and the Gran Consiglio ("Great Council"). The first was initially composed of 40 to 60 members and approved the laws and modifications to the Constitutional Chart. The second initially had from 80 to 120 members and proposed the laws. Both councils discussed treaties, the choice of a Directory, and the determination of tributes. The legislative corps included men like Pietro Verri, Giuseppe Parini and the scientist Alessandro Volta. The electors had to be landowners or wealthy.

The Cisalpine directory was composed of five members and exercised executive power.[1] Directors included local politicians such as Giovanni Galeazzo Serbelloni, the first president, and Francesco Melzi d'Eril, who would later serve as vice president of the Italian Republic.[1] The Directory chose its secretary and appointed the six ministers: for justice, war, foreign affairs, internal affairs, police, and finance. The supreme authority, however, was the commander of the French troops. The republic also adopted the French Republican Calendar.

Each department had its own local directory of five members, as did communes between 3,000 and 100,000 inhabitants. The biggest communes were divided into municipalities, with a central joint commission to handle the general affairs of the cities. The smallest communes were united in districts with a single municipality, with each commune having its own municipal agent.

Second constitution

[edit]

The first constitution did not have a long life. On 14 Fructidor, year VI (31 August 1798), the French ambassador Claude-Joseph Trouvé (who was only thirty years old) dismissed the Directory, and the next day he promulgated a new constitution with a stronger executive power.

The departments numbered eleven again, now covering larger geographical areas: Olona (Milan), Alto Po (Cremona), Serio (Bergamo), Adda and Oglio (Morbegno), Mella (Brescia), Mincio[3] (Mantua), Panaro (Modena), Crostolo (Reggio), Reno (Bologna), Basso Po (Ferrara), Rubicone (Forlì). The membership of the local directories was reduced to three, and the municipalities for communes between 3,000 and 10,000 inhabitants were disbanded.

Trouvé appointed the new Directory, which had stronger powers, and a new parliament composed of two councils: the Anziani ("Elders") and the Giuniori ("Juniors"). The first was composed of 40 elected members together with the former directors. The second had 80 members.

A new coup d'état, attempted by French general Guillaume Marie Anne Brune the next autumn, was disavowed by the French Directory on 17 Frimaire (7 December).

Treaty of alliance

[edit]Formally, the Cisalpine Republic was an independent state allied with France, but the treaty of alliance established the effective subalternity of the new republic to France. The French, in fact, had control over the local police and left an army consisting of 25,000 Frenchmen, financed by the Republic. The Cisalpines were also required to form another army of 35,000 of their own men to take part in French campaigns.

On 4 March 1798, the Directory presented this treaty to the Great Council for ratification. The council did not agree with the terms and delayed taking a decision, but in the end, the French general Berthier compelled acceptance by the members. The Elders, however, refused it from the very beginning, as the new state was unable to finance the requested institutions. Berthier threatened to impose a military government but was later replaced by General Brune. The latter, after replacing some Elders and Juniors, achieved the signing of the treaty on 8 June.

Relationship with Switzerland

[edit]Due to multiple attempts by the Cisalpine government to annex the Italian-speaking Swiss territories south of the Alps, relations with the Swiss Confederacy were strained.[1] The Cisalpine Republic ended up taking control of Valtellina from the Three Leagues and Campione d'Italia and annexing them.[1] A Cisalpine attempt to conquer Lugano by surprise failed in 1797.

Second republic

[edit]

After the defeat of France at the Battle of Cassano in April 1799 during the War of the Second Coalition, the republic was occupied by General Suvorov's Russian and Austrian forces, which appointed a provisional administration led by the Imperial Commission of the Mantuan Count Luigi Cocastelli. They departed only on 30 May 1800, just a few days before the French won the Battle of Marengo.

The Cisalpine Republic was restored by Napoleon on 15 Prairial, year VIII (4 June 1800). On 28 Prairial (17 June), the First Consul appointed an Extraordinary Commission of Government of nine members and a legislative Consulta: the final list of the executive and legislative institutions was published on 5 Messidor (24 June). On 16 Messidor (6 July) all the acts issued during the Austrian occupation were annulled, and afterwards, the tricolour flag was restored.

Napoleon's new victories gave him a chance to stabilize the political situation in all of northern Italy. On 3 Vendémiaire, year IX (25 September), the powers of the Extraordinary Commission were concentrated in the hands of a more restricted Committee of Government, composed of three members: Giovan Battista Sommariva, Sigismondo Ruga and Francesco Visconti, reflecting the institution of the French Consulate. On 21 Vendémiaire (13 October), owing to the refusal of the escaped King Charles Emmanuel IV of Sardinia to sign a treaty of peace settling the situation of the occupied Piedmont, Napoleon ordered the annexation of Novara to the republic, shifting its western border from the river Ticino to the River Sesia. After the surrender of Austria and the signing of the Treaty of Lunéville on 9 February 1801, the territory of the republic was extended to the east as well, placing the frontier with the Holy Roman Empire on the River Adige without the exceptions agreed in Campo Formio. On 23 Floreal (13 May), the territory of the republic was divided into 12 departments, adding Agogna (Novara), restoring Lario and abolishing Adda-e-Oglio.

On 21 Brumaire, year X (12 November), an Extraordinary Cisalpine Consulta was summoned in Lyon. In January 1802, the Consulta decided to change the name of the State to the Italian Republic, when Napoleon had himself elected president, on 24 January, on the advice of Talleyrand. Two days later, in a scene officially commemorated by Nicolas-André Monsiau, Bonaparte appeared in the Collège de la Trinité of Lyon, attended by Murat, Berthier, Louis Bonaparte, Hortense and Joséphine de Beauharnais, and heard the assembled notables proclaim the Italian Republic. On 21 Pluviôse (10 February), the new constitutional government was proclaimed in Milan by Sommariva and Ruga. The same day, the Gregorian calendar was restored.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cisalpine Republic in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ John Debrett, A Collection of State Papers Relative to the War Against France Now Carrying on by Great Britain and the Several Other European Powers (1798) 96. Debrett's.

- ^ The Constitution was written so fast that the department of Mincio was erroneously listed as Milano.

Sources

[edit]- Historical database of Lombard laws (in Italian)