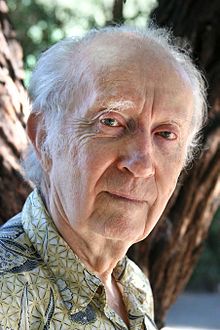

Clare Palmer | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1967 (age 56–57) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford |

| Notable work | Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking (1998) Animal Ethics in Context (2010) |

| Institutions | Texas A&M University |

Main interests | Environmental ethics Animal ethics |

Clare Palmer (born 1967) is a British philosopher, theologian and scholar of environmental and religious studies. She is known for her work on environmental and animal ethics. She was appointed as a professor in the Department of Philosophy at Texas A&M University in 2010. She had previously held academic appointments at the Universities of Greenwich, Stirling, and Lancaster in the United Kingdom, and Washington University in St. Louis in the United States, among others.

She has published three sole-authored books: Environmental Ethics (ABC-CLIO, 1997), Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking (Oxford University Press, 1998) and Animal Ethics in Context (Columbia University Press, 2010). She has also published two co-authored books and has edited (or co-edited) seven collections or anthologies. She is a former editor of the religious studies journal Worldviews: Environment, Culture, Religion, and a former president of the International Society for Environmental Ethics.

In Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking, which was based on her doctoral research, Palmer explores the possibility of a process philosophy-inspired account of environmental ethics, focussing on the work of Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne. She ultimately concludes that a process ethic is not a desirable approach to environmental questions, in disagreement with some environmentalist thinkers. In Animal Ethics in Context, Palmer asks about responsibilities to aid animals, in contrast to the typical focus in animal ethics on not harming animals. She defends a contextual, relational ethic according to which humans will typically have duties to assist only domestic, and not wild, animals in need. However, humans will often be permitted to assist wild animals, and may be obligated to do so if there is a particular (causal) relationship between humans and the animals' plight.

Career

[edit]

Palmer read for a BA (Hons) in theology at Trinity College, Oxford, graduating in 1988, before reading for a doctorate in philosophy at the same university. From 1988 to 1991, she was based at Wolfson College, before becoming a Holwell Senior Scholar at The Queen's College.[1] In 1992, having previously published book reviews, Palmer published her first research publication,[1] "Stewardship: A Case Study in Environmental Ethics", in the edited collection The Earth Beneath: A Critical Guide to Green Theology, published by SPCK. She was also, along with Ian Ball, Margaret Goodall, and John Reader, a co-editor of the volume.[2] She graduated from Oxford in 1993 with a doctorate from The Queen's College;[3] her thesis focussed on process philosophy and environmental ethics.[4] She worked as a research fellow in philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1992 to 1993, before becoming a lecturer in environmental studies at the University of Greenwich. She worked at Greenwich from 1993 until 1997, after which she spent a year as a research fellow at the University of Western Australia.[1] In 1997, she published her first[1] book: Environmental Ethics was published with ABC-CLIO.[5] Additionally, the first issue of Worldviews: Environment, Culture, Religion (later renamed Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology), a peer reviewed academic journal in religious studies, was published. Palmer was the founding editor,[6] and she remained editor until 2007.[1]

Palmer returned to working in the UK in 1998, becoming a lecturer in religious studies at the University of Stirling.[1] That same year, she published Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking with the Clarendon Press imprint of Oxford University Press.[7] This was based ultimately on her doctoral dissertation.[4] The book was reviewed by William J. Garland in Ethics,[8] Richard J. Matthew in Environment,[9] and Stephen R. L. Clark in Studies in Christian Ethics,[10] Timothy Sprigge in Environmental Ethics,[11] and Randall C. Morris in The Journal of Theological Studies.[4] It was also the subject of a "forum" in the journal Process Studies. Introduced by David Ray Griffin, the forum's editor,[12] it featured a "Palmer on Whithead: A Critical Evaluation" by John B. Cobb[13] and "Clare Palmer's Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking: A Hartshornean Response" by Timothy Menta,[14] as well as a reply by Palmer herself.[15] The next year, Cobb published "Another Response to Clare Palmer" in the same journal.[16]

Palmer remained at Stirling for several years before taking up the post of senior lecturer in philosophy at Lancaster University in 2001. While at Lancaster, she became the vice-president of the International Society for Environmental Ethics (ISEE). In 2005, she moved to Washington University in St. Louis, where she took up the role of associate professor, jointly appointed in departments of philosophy and environmental studies.[1] The same year, the five-volume encyclopaedia Environmental Ethics, co-edited by Palmer and J. Baird Callicott, was published by Routledge,[17] and, in the subsequent year, she was part of "The Animal Studies Group" which published the collection Killing Animals with the University of Illinois Press.[18] While at Washington, she was also the editor of both Teaching Environmental Ethics (Brill, 2007)[19] and Animal Rights (Ashgate Publishing, 2008).[20] In 2007, she was elected president of the ISEE, a position she held until 2010.[1]

In 2010, Palmer was appointed professor in the Department of Philosophy at Texas A&M University.[1] The same year saw the publication of her Animal Ethics in Context with Columbia University Press.[21] Among reviews of this book were pieces by Bernard Rollin in Anthrozoös,[22] Jason Zinser in The Quarterly Review of Biology,[23] J. M. Dieterle in Environmental Ethics,[24] Scott D. Wilson in Ethics[25] and Daniel A. Dombrowski in the Journal of Animal Ethics.[26] She has subsequently published papers on the theme of assisting animals in the wild—ideas discussed in her Animal Ethics in Context[27]—in animal-focussed journals,[28][29] prompting commentary from Joel MacClellan,[30] Gordon Burghart,[31] and Catia Faria.[32]

While at Texas A&M, Palmer co-edited the 2011 Veterinary Science: Humans, Animals and Health with Erica Fudge[33] and the 2014 Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World: Values, Philosophy, and Action with Calliott, Ricardo Rozzi, Steward Pickett, and Juan Armesto.[34] In 2015, Wiley-Blackwell published Palmer's Companion Animal Ethics, co-authored with Peter Sandøe and Sandra Corr,[35] and, in 2023, Wiley published her Wildlife Ethics: The Ethics of Wildlife Management and Conservation, which was co-authored with Bob Fischer, Christian Gamborg, Jordan Hampton, and Sandøe.

Thought

[edit]Environmental ethics

[edit]

In Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking, Palmer examines whether process philosophy, in particular the philosophies of Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne, can provide an appropriate background for engaging in environmental ethics.[8] Process thought, Clark notes, has frequently appealed more to theologically inclined environmental ethicists than classical theism; in particular, the views of Hartshorne and Cobb have been influential.[10]

Palmer first sets forth a process ethic. The ethic she presents is similar to John Stuart Mill's utilitarianism, but while Mill's approach locates value in pleasure, Palmer's process ethic locates value in "richness" of experience. She then compares this ethic to several dominant schools in environmental ethics: "individualist consequentialism" (as championed by Peter Singer, Donald VanDeVeer and Robin Attfield), "individualist deontological environmental ethics" (including the diverse positions presented by Albert Schweitzer, Kenneth Goodpastor, Tom Regan and Paul W. Taylor), "collectivist environmental ethics" (including those thinkers who advocate doing what is best for nature as a whole, such as Aldo Leopold and Callicott in his earlier work) and deep ecology.[8]

Process ethics, Palmer argues, is closer to individualist consequentialism than individualist deontological environmental ethics. In considering collectivist environmental ethics, Palmer asks how process thinkers could approach natural collectives, such as ecosystems. She argues that Whitehead could view them as single entities with a good of their own, while Hartshorne could not. The primary difference between process ethics and collectivist environmental ethics, however, is that the former has a theological basis. The advocates of deep ecology have previously sought support from the views of Whitehead; two affinities are the shared holism and a shared concern with the extension of the self, but Palmer finds that the views of Whitehead and the views of the deep ecology advocate Arne Næss differ in these areas.[8]

The book was not intended to either present or defend any particular position in environmental ethics, but rather to explore what process philosophers could say or have said about environmental issues.[15] There are, for Palmer, two key problems with a process approach to environmental ethics. The first concerns the value of human and nonhuman life; for process thinkers, the latter will always be trumped by the former in terms of value. The second concerns human perspectives; as process philosophy invariably models interpretation of all entities on human experience, it is not well-suited to characterising non-human nature. Palmer thus concludes that process philosophy does not provide a suitable basis for environmental ethics.[8]

The book was hailed as an important addition to the literature in both environmental ethics and process philosophy.[4] Garland offered two challenges to Palmer's claims. First, he challenged her linking of process ethics with individualist consequentialism, arguing that it is instead somewhere between individualist consequentialism and deep ecology. Second, he challenged Palmer's claim that process philosophers will always favour human ends over nonhuman ends.[8] Cobb and Menta, though both welcoming her consideration of process philosophy, challenged Palmer's interpretation of the philosophy of Whitehead and Hartshorne on a number of points.[13][14]

In addition to writing on process approaches to the environment, Palmer has contributed to Christian environmental ethics more broadly,[36][37][38] urban environmental ethics,[39][40] and scholarship on the environment in the work of English writers.[41][42] Much of her work in environmental ethics has explored questions concerning animals, including the tension between protecting individuals and protecting species.[39][40][43][44]

Animal ethics

[edit]

Palmer does not explicitly connect Environmental Ethics and Process Thought to Animal Ethics in Context, her second monograph; the latter does, however, address environmental ethics, insofar as it offers an attempt to bridge environmental ethics and animal ethics.[26] In contrast to more typical approaches to animal ethics which focus on the ethics of harming animals, Palmer asks, in Animal Ethics in Context, about the ethics of aiding animals,[25] with a focus on the distinction between wild and domestic animals.[26] She follows mainstream animal ethics approaches in arguing that humans have a prima facie duty not to harm any animal. However, when it comes to aiding animals, she argues that human obligations differ depending on the context.[26]

Palmer begins by defending the claim that animals have moral standing, and then surveys three key approaches to animal ethics; utilitarian approaches, animal rights approaches, and capabilities approaches. All are lacking, she argues, as they are fundamentally capacity-oriented, and thus unable to properly take account of human relationships to animals. However, her approach leans more strongly towards a Regan-inspired rights view. She next identifies different kinds of relations humans may have with animals: affective, contractual and, most significantly, causal.[25]

Palmer identifies the laissez-faire intuition (LFI), which is the intuition that humans do not have an obligation to aid wild animals in need. There are three forms of the LFI:

- The strong LFI, according to which humans may not harm or assist wild animals.

- The weak LFI, according to which humans may not harm wild animals, but may assist them, despite lacking an obligation to do so.

- No-contact LFI, according to which humans may not harm wild animals, but may assist them, and may gain obligations to assist them if humans are responsible for the animals' plight.[25]

Ultimately, Palmer endorses the no-contact version of the LFI. She defends the distinction between doing and allowing harm, and then defends the idea that humans have different positive obligations towards domestic animals and wild animals. At the centre of Palmer's approach is the fact that humans are causally responsible for the hardship faced by some animals, but not the hardship faced by others. She then deploys this philosophy in a number of imagined cases in which humans have varying relations to particular animals in need. She closes the book by considering possible objections, including the idea that her approach would not require someone to save a drowning child at little cost to themselves.[25]

Thus, Palmer argues that humans are not normally required to aid wild animals in need.[27][29] The philosopher Joel MacClellan, a critic of intervention, challenges Palmer on three grounds: first, he says that the difference between our obligations to domestic and wild animals in Palmer's thought experiments could be justified on scientific, rather than moral, grounds; second, he challenges Palmer's characterisation of wildness as a relationship, rather than a capacity, arguing that a description of an animal as wild likely conveys that the animal has certain capacities lacked by domestic animals; and, third, he suggests that just as a utilitarian approach to wild animal suffering may demand too much, Palmer's contextual approach may permit too much, by allowing the policing of nature. The affinities between utilitarian and contextualist approaches, MacClellan argues, come from their shared idea of what is and is not valuable.[30] The pro-intervention philosopher Catia Faria criticises Palmer's argument from the other direction. Faria challenges Palmer's account by pointing to the counter-intuitive conclusions it would reach, Faria claims, in cases of assisting humans with whom an individual does not have significant relationships. Unless Palmer is willing to deny that humans have obligations to help suffering distant humans, Faria argues, the account cannot justify not aiding animals.[32]

In addition to contextual animal ethics and her exploration of animals in environmental ethics, Palmer has written on disenhanced animals (i.e., animals that have been engineered to lose certain capacities)[46][47] and companion animals.[48][49] The latter topic was the focus of her co-authored text Companion Animal Ethics,[35] which explores ethical issues concerning companion animals, including feeding, medical care, euthanasia and others.[50]

Selected bibliography

[edit]In addition to her books, Palmer has written or co-written over 30 articles in peer-reviewed journals and over 25 articles in scholarly collections, as well as various encyclopaedia articles and book reviews.[1] Editorial duties have included acting as an associate editor for Callicott and Robert Frodeman's two-volume encyclopaedia Environmental Philosophy and Ethics and editing the journal Worldviews. Palmer has served on the editorial boards of two Springer series (first, the International Library of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Ethics, and, second, Ecology and Ethics) and one Sydney University Press series: Animal Publics. She has served on the editorial boards of various journals, including Environmental Humanities; Ethics, Policy and Environment; Environmental Ethics; Environmental Values; the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics; and the Journal for the Study of Religion, Culture and Nature.[1]

Books

[edit]- Palmer, Clare (1997). Environmental Ethics. Santa Barbara and Denver: ABC-CLIO.

- Palmer, Clare (1998). Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Palmer, Clare (2010). Animal Ethics In Context. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sandøe, Peter, Sandra Corr and Clare Plamer (2015). Companion Animal Ethics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Palmer, Clare, Bob Fischer, Christian Gamborg, Jordan Hampton and Peter Sandøe (2023). Wildlife Ethics: The Ethics of Wildlife Management and Conservation. Oxford: Wiley.

Edited collections and anthologies

[edit]- Ball, Ian, Margaret Goodall, Clare Palmer and John Reader, eds. (1992). The Earth Beneath. London: SPCK.

- Callicott, J. Baird, and Clare Palmer, eds. (2005). Environmental Philosophy, Vols. 1–5. London and New York: Routledge.

- The Animal Studies Group, ed. (2006). Killing Animals. Champaign-Urbana: Illinois University Press.

- Palmer, Clare, ed. (2007). Teaching Environmental Ethics. Leiden: Brill.

- Palmer, Clare, ed. (2008). Animal Rights. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Fudge, Erica, and Clare Palmer, eds. (2014). Veterinary Science: Humans, Animals and Health. London: Open Humanities Press.

- Rozzi, Ricardo, Steward Pickett, Clare Palmer, Juan Armesto and J. Baird Callicott, eds. (2014). Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World: Values, Philosophy, and Action. Dordrecht: Springer.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Palmer, Clare (October 2015). "CV" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ^ Ball, Ian, Margaret Goodall, Clare Palmer and John Reader, eds. (1992). The Earth Beneath. London: SPCK.

- ^ "Clare Palmer; Professor Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Texas A&M University. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Morris, Randall C. (2001). "Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking" The Journal of Theological Studies 52 (1): 499–501. doi:10.1093/jts/52.1.499.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (1997). Environmental Ethics. Santa Barbara and Denver: ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (1997). "Editorial". Worldviews: Environment, Culture, Religion 1 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1163/156853597X00173

- ^ Palmer, Clare (1998). Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f Garland, William J. (2000). "Clare Palmer, Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking" Ethics 110 (4): 859–861. doi:10.1086/233388.

- ^ Matthew, Richard A. (1999). "Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking". Environment 41 (7): 30.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen R. L. (1999). "Book review: Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking, by Clare Palmer". Studies in Christian Ethics 12 (2): 89–91. doi:10.1177/095394689901200209

- ^ Sprigge, T. L. S. (2000). "Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking". Environmental Ethics 22 (2): 191. doi:10.5840/enviroethics200022235.

- ^ Griffin, David R. (2004). "Forum Introduction". Process Studies 33 1: 3. doi:10.5840/process200433122

- ^ a b Cobb, John B. (2004). "Palmer on Whithead: A Critical Evaluation". Process Studies 33 1: 4–23. doi:10.5840/process200433123

- ^ a b Menta, Timothy (2004). "Clare Palmer's Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking: A Hartshornean Response". Process Studies 33 1: 24–45. doi:10.5840/process200433124

- ^ a b Palmer, Clare (2004). "Response to Cobb and Menta". Process Studies 33 1: 46–70. doi:10.5840/process200433125

- ^ Cobb, John B. (2005). "Another Response to Clare Palmer". Process Studies 34 1: 132–5. doi:10.5840/process200534127

- ^ Callicott, J. Baird, and Clare Palmer, eds. (2005). Environmental Philosophy, Vols. 1–5. London and New York: Routledge.

- ^ The Animal Studies Group, ed. (2006). Killing Animals. Champaign-Urbana: Illinois University Press.

- ^ Palmer, Clare, ed. (2007). Teaching Environmental Ethics. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Palmer, Clare, ed. (2008). Animal Rights. Farnham: Ashgate.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2010). Animal Ethics in Context. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Rollin, Bernard (2012). "Book review: Animal Ethics in Context Clare Palmer". Anthrozoös 25 (2): 250–1. doi:10.2752/175303712X13316289505666.

- ^ Zinser, Jason (2012). "Animal Ethics in Context by Clare Palmer". The Quarterly Review of Biology 87 (3): 246–7. doi:10.1086/666786.

- ^ Dieterle, J. M. (2011). "Animal Ethics in Context". Environmental Ethics 33 (2): 223–4. doi:10.5840/enviroethics201133223.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, Scott D. (2011). "Animal Ethics in Context by Palmer, Claire". Ethics 121 (4): 824–8. doi:10.1086/660788.

- ^ a b c d Dombrowski, Daniel A. (2012). "Animal Ethics in Context by Clare Palmer". Journal of Animal Ethics 2 (1): 113–5. doi:10.5406/janimalethics.2.1.0113.

- ^ a b Dorado, Daniel (2015). "Ethical Interventions in the Wild. An Annotated Bibliography". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 219–38. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-dora.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2013). "What (If Anything) Do We Owe Wild Animals?" Between the Species 16 (1): 15–38. doi:10.15368/bts.2013v16n1.4.

- ^ a b Palmer, Clare (2015). "Against the View That We Are Normally Required to Assist Wild Animals". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 203–10. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-palm.

- ^ a b MacClellan, Joel (2013). "What the Wild Things Are: A Critique on Clare Palmer's 'What (If Anything) Do We Owe Animals?'" Between the Species 16 (1): 53–67. doi:10.15368/bts.2013v16n1.1.

- ^ Burghart, Gordon (2013). "Beyond Suffering – Commentary on Clare Palmer". Between the Species 16 (1): 39–52. doi:10.15368/bts.2013v16n1.6.

- ^ a b Faria, Catia (2015). "Disentangling Obligations of Assistance. A Reply to Clare Palmer's 'Against the View That We Are Usually Required to Assist Wild Animals'". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 211–18. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-fari.

- ^ Fudge, Erica, and Clare Palmer, eds. (2014). Veterinary Science: Humans, Animals and Health. London: Open Humanities Press.

- ^ Rozzi, Ricardo, Steward Pickett, Clare Palmer, Juan Armesto and J. Baird Callicott, eds. (2014). Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World: Values, Philosophy, and Action. Dordrecht: Springer.

- ^ a b Sandøe, Peter, Sandra Corr and Clare Plamer (2015). Companion Animal Ethics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Palmer, Claire (1994). "A Bibliographical Essay on Environmental Ethics". Studies in Christian Ethics 7 (1): 68–97. doi:10.1177/095394689400700107.

- ^ Palmer, Claire (1994). "Some Problems with Sustainability". Studies in Christian Ethics 7 (1): 52–62. doi:10.1177/095394689400700105.

- ^ Gill, Robin (1994). "A Response to Clare Palmer". Studies in Christian Ethics 7 (1): 63–7. doi:10.1177/095394689400700106.

- ^ a b Palmer, Clare (2003). Placing Animals in Urban Environmental Ethics". Journal of Social Philosophy 34 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1111/1467-9833.00165.

- ^ a b Palmer, Clare (2003). "Animals, Colonisation and Urbanisation". Philosophy and Geography 6 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1080/1090377032000063315.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2002). "Christianity, Englishness and the Southern English Countryside: A Study of the Work of H.J. Massingham". Social and Cultural Geography 3 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1080/14649360120114125.

- ^ Palmer, Clare, and Emily Brady (2007). "Landscape and Value in the Work of Alfred Wainwright (1907–1991)". Landscape Research 32 (4): 397–421. doi:10.1080/01426390701449778.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2004). "'Respect for nature' in the Earth Charter: The value of species and the value of individuals". Ethics, Place & Environment 7 (1–2): 97–107. doi:10.1080/1366879042000264804.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2009). "Harms to Species? Species, Ethics and Climate Change: The Case of the Polar Bear". Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics and Public Policy 23 (2): 587–603.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2010). Animal Ethics in Context. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2011). "Animal Disenhancement and the Non-Identity Problem: A Response to Thompson". Nanoethics 5 (1): 43–8. doi:10.1007/s11569-011-0115-1.

- ^ Sandøe, Peter, Paul M. Hocking, Sophie Collins, Björn Forkman, Kirsty Haldane, Helle H. Kristensen and Clare Palmer (2014). "The Blind Hens' Challenge: Does it undermine the view that only welfare matters in our dealings with animals?" Environmental Values 23 (6): 727–42.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2013). "Companion Cats as Co-Citizens? Comments on Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka's Zoopolis". Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review 52 (4): 759–67. doi:10.1017/S0012217313000826.

- ^ Palmer, Clare (2012). "Does Breeding a Bulldog Harm It? Breeding, Ethics and Harm to Animals". Animal Welfare 21: 157–66. doi:10.7120/09627286.21.2.157

- ^ Hiestand, Karen (2016). "Companion Animal Ethics". Veterinary Record 178 (11): 269. doi:10.1136/vr.i1425.

External links

[edit]- Clare Palmer at Texas A&M University

- "Editorial Profile: Clare Palmer", Environmental Humanities

- "Clare Palmer on her book Animal Ethics in Context", Rorotoko interview