| |

| |

| |

| Established | 1913 (officially opened in 1916) |

|---|---|

| Location | 11150 East Boulevard Cleveland, Ohio |

| Coordinates | 41°30′32″N 81°36′42″W / 41.50889°N 81.61167°W |

| Collection size | 66,500 works[1] |

| Visitors | 685,336 (2023)[2] |

| Director | William M. Griswold[3] |

| Website | www |

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is an art museum in Cleveland, Ohio, United States. Located in the Wade Park District of University Circle, the museum is internationally renowned for its substantial holdings of Asian and Egyptian art and houses a diverse permanent collection of more than 61,000 works of art from around the world.[4] The museum provides free general admission to the public. With a $920 million endowment (2023), it is the fourth-wealthiest art museum in the United States.[5][6] With about 770,000 visitors annually (2018), it is one of the most visited art museums in the world.[7]

History

[edit]

Beginnings

[edit]The Cleveland Museum of Art was founded as a trust in 1913 with an endowment from prominent Cleveland industrialists Hinman Hurlbut, John Huntington, and Horace Kelley.[8] The neoclassical, white Georgian Marble, Beaux-Arts building was constructed on the southern edge of Wade Park, at the cost of $1.25 million.[9] Wade Park and the museum were designed by the local architectural firm, Hubbell & Benes, with the museum planned as the park's centerpiece.[10] The 75-acre (300,000 m2) green space takes its name from philanthropist Jeptha H. Wade, who donated part of his wooded estate to the city in 1881.[11] The museum opened its doors to the public on June 6, 1916, with Wade's grandson, Jeptha H. Wade II, proclaiming it, "for the benefit of all people, forever".[12] Wade, like his grandfather, had a great interest in art and served as the museum's first vice-president; in 1920 he became its president.[13] Today, the park, with the museum still as its centerpiece, is on the National Register of Historic Places.[14]

Mid to late 20th century expansion

[edit]

In March 1958, the first addition to the building opened, doubling the museum's floorspace. This addition, which was on the north side of the original building, was designed by the Cleveland architectural firm of Hayes and Ruth[15]. They designed new gallery space and a new art library.

The museum again expanded in 1971 with the opening of the North Wing. With its stepped, two-toned granite facade, the addition designed by modernist architect Marcel Breuer provided angular lines in distinct contrast with the flourishes of the 1916 building's neoclassical facade. The museum's main entrance was shifted to the North Wing. The auditorium, classrooms, and lecture halls were also moved into the North Wing, allowing their spaces in the Original Building to be renovated as gallery space.

In 1983, a West Wing, designed by the Cleveland architectural firm of Dalton, van Dijk, Johnson, & Partners, was completed. This provided larger library space, as well as nine new galleries.

Between 2001 and 2012, the 1958 and 1983 additions were demolished. A new wrap-around building, and east and west wings were constructed. Designed by Rafael Viñoly, this $350 million project doubled the museum's size to 592,000 square feet (55,000 m2). To integrate the new east and west wings with the Breuer building to the north, a new structure was built along the south side of the 1971 addition, creating extensive new gallery space on two levels, as well as providing for a museum store and other amenities. Viñoly covered the space created by the demolition of the 1958 and 1983 structures with a glass-roofed atrium. The east wing opened in 2009, and the north wing and atrium in 2012.[16] The West Wing opened on January 2, 2014.[17]

Expansion in the 21st century

[edit]

The museum's building and renovation project, "Building for the Future",[12] began in 2005 and was originally targeted for completion in 2012 (though it was not completed until 2013)[7] at projected costs of $258 million.[18] The museum celebrated the official completion of the renovation and expansion project with a grand opening celebration held on December 31, 2013, and additional activities that continued through the first week of 2014.[19] The $350 million project—two-thirds of which was earmarked for the complete renovation of the original 1916 structure—added two new wings, and was the largest cultural project in Ohio's history.[12] The new east and west wings, as well as the enclosing of the atrium courtyard under a soaring glass canopy, have brought the museum's total floor space to 592,000 square feet (55,000 m2) (an increase of approximately 65%).

The first phase of the project had $9.3 million in cost overruns; the opening was delayed by 9 months. Museum director Timothy Rub assured the public that the increase in quality would be worth both the wait and expense.[20] In June 2008, after being closed for nearly three years for the overhaul, the museum reopened 19 of its permanent galleries to the public in the renovated 1916 building main floor.

On June 27, 2009, the newly constructed East Wing (which contains the Impressionist, Contemporary, and Modern art collections) opened to the public.

On June 26, 2010, the ground level of the 1916 building reopened. It now houses the collections of Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Sub-Saharan African, Byzantine, and Medieval art.[21] The expanded museum includes enhanced visitor amenities, such as new restrooms, an expanded store and café, a sit-down gourmet restaurant, parking capacity increased to 620 spaces, and a 34,000 square feet (3,200 m2) glass-covered courtyard.

On June 12, 2021, Cleveland Museum of Art opened a community arts center in Cleveland's Clark-Fulton neighborhood. It hosts former Parade the Circle floats, displays and art that were previously in temporary storage.[22]

Wade Park

[edit]Wade Park includes an outdoor gallery displaying part of the museum's holdings in the Wade Park Fine Arts Garden. The bulk of this collection is located between the original 1916 main entrance to the building and the lagoon. Highlights of the public sculpture include the large cast of Chester Beach's 1927 Fountain of the Waters; a monument to the Polish expatriate and American Revolutionary War-hero Tadeusz Kościuszko; and the 1928 bronze statuary sundial by Frank Jirouch, Night Passing the Earth to Day, which sits across Wade Lagoon from the museum, near the park's entrance on Euclid Avenue.

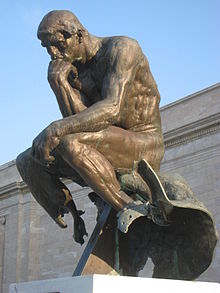

Auguste Rodin's The Thinker is installed at the top of the museum's main staircase. After being partially destroyed in a 1970 bombing (allegedly by the Weathermen),[23] the statue was never restored. Art historians knew that Rodin was involved in the original casting of this sculpture, and it was the last bronze casting of The Thinker made during Rodin's lifetime. The 1970 damage (noted on a plaque since mounted at the base of the statue's pedestal) is considered to have made this casting unique among the more than twenty original large castings of this work.[24]

Collections

[edit]

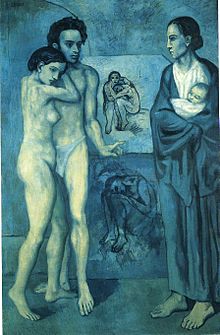

The Cleveland Museum of Art divides its collections into 16 departments, including Chinese Art, Modern European Art, African Art, Drawings, Prints, European Art, Textiles and Islamic Art, American Painting and Sculpture, Greek and Roman Art, Contemporary Art, Medieval Art, Decorative Art and Design, Pre-Columbian and Native North American Art, Japanese and Korean Art, Indian and Southeast Asian Art, and Photography. Artists represented by significant works include Olivuccio di Ciccarello, Botticelli, Giambattista Pittoni, Caravaggio, El Greco, Poussin, Rubens, Frans Hals, Richard Hunt, Gerard David, Goya, J. M. W. Turner, Dalí, Matisse, Renoir, Gauguin (The Call), Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Cole, Corot, Thomas Eakins, Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Picasso, and George Bellows. The museum has been active recently in acquiring later 20th-century art, having added important works by Warhol, Jackson Pollock, Christo, Anselm Kiefer, Ronald Davis, Larry Poons, Leon Kossoff, Jack Whitten, Morris Louis, Jules Olitski, Chuck Close, Robert Mangold, Ching Ho Cheng, Mark Tansey and Sol LeWitt, among others.

The museum's African art collection consists of 300 traditional, sub-Saharan works from the Bini, Congo, Senufo, and Yoruba peoples, mostly donated by Cleveland collector Katherine C. White.[25] The museum is especially strong in the field of Asian art, possessing one of the best collections in the U.S.[further explanation needed][26]

In June 2004, the museum acquired an ancient bronze sculpture of Apollo Sauroktonos, believed to be an original work by Praxiteles of Athens. Because the work has a contested provenance, the museum continues to study the dating and attribution of the sculpture. In 2011, Michael Bennet, the Greek and Roman arts curator, announced that he had dated the piece to 350 B.C. to 250 B.C.[27] In 2013, the museum held a focus exhibition on the statue. It announced reattribution of the work as Apollo the Python-Slayer, and said that the statue was almost certainly an original work by Praxiteles himself, and that laboratory investigations and expert testimony conclusively show the bronze was neither a recent discovery nor recovered from the sea.[28]

In 2008, the United States Postal Service selected the Cleveland Museum's famed Botticelli painting entitled Virgin and Child with the Young John the Baptist as the Christmas stamp for that year.[29]

Modern European Painting and Sculpture

[edit]

The Cleveland Museum of Art's Modern European Painting and Sculpture collection holds pieces dating from 1800 to 1960, and contains about 537 pieces. The collection contains Impressionism and Post-impressionism works, avant-garde art styles, and German Expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit art.[30]

-

Cupid and Psyche, by Jacques-Louis David, 1817

-

Reading, by Berthe Morisot, 1873

-

The Red Kerchief Portrait of Madame Monet, by Claude Monet

European Painting and Sculpture

[edit]This collection holds pieces dating from 1500 to 1800, with major works representing Italian Baroque, Spanish Baroque, Italian Renaissance, as well as significant French, British, and Dutch paintings.[31]

-

The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew, Caravaggio, 1607 - Post-Restoration

-

Saint Paul the Hermit, Mattia Preti, 1663

-

Portrait of a Woman, by Cornelius Johnson, 1619

-

Tieleman Roosterman, Frans Hals, 1634

-

Holy Family on the Steps, Nicolas Poussin, 1648

American Painting and Sculpture

[edit]The collection is concise, containing about 300 paintings and 90 sculptures. Major attractions in the collection include William Sideny Mount's The Power of Music, Frederich Edwin Church's Twilight in the Wilderness, and Albert Pinkham Ryder's The Racetrack (Death on a Pale Horse). A number of Cleveland-based artists are also included in the museum's holdings, placing an emphasis on local art.[32]

-

The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse), by Albert Pinkham Ryder

Photography

[edit]The Cleveland Museum of Art contains a small collection of fine art photography, dating back to 1893. Of special note are pieces from photography's first contributors, particularly French, English, and American photographers. Other highlights of the collection are "photography with complete sets of The North American Indian by Edward S. Curtis and Camera Work; surrealist photography created primarily between the two world wars; and Cleveland-specific subject matter produced by regional and national photographers".[33]

-

A Nakoaktok Chief's Daughter

-

Walker Evans, Allie Mae Burroughs, Wife of a Cotton Sharecropper, Hale County, Alabama, 1936.

Decorative Art and Design

[edit]An internationally renowned collection, the Decorative Art and Design collection "consists of useful objects in which the form and decoration are the primary focus, not objects intended purely as sculpture"[34]

-

A cabinet from 1690

Asian Art

[edit]-

Cloudy Mountains, Mi Youren, 1130

-

Dragon; Tiger, Muqi, 1250–1279

Ingalls Library

[edit]In addition to its comprehensive collection of fine art, the Cleveland Museum of Art is also home to the Ingalls Library, one of the largest art libraries in the United States. As part of the initial 1913 plan by the museum's founders, a library of 10,000 volumes was to be assembled, to include photographs and archival works. By the 1950s, the collection of books alone had surpassed 37,000 and the photographic collection neared 47,000. By the 21st century, the library had more than 500,000 volumes (and 500,000 digitized slides); renovation of the library space was one of the focal points in the museum's $350 million expansion. Established in 1989, the Museum Archives houses documentation about the Cleveland Museum of Art's role in the local community and the institutions the Cleveland Museum of Art has interacted with since its founding.[35]

ARTLENS Gallery

[edit]

The ARTLENS Gallery is a series of interactive displays and a mobile app that allow visitors to view and interact with the museum's digitized collection. ARTLENS is divided into four components:[36][37]

- The ArtLens Wall is a 40-foot display that lets visitors browse and scale all works that are displayed in the museum, as well as some artworks that are not. The wall rotates through artworks in groups organized by criteria such as type, shape, and color.[37]

- The ArtLens Exhibition is a rotating selection of artworks that are showcased through digital gesture-based games and activities. Examples of these activities are automatically matching the shape of a user's hand gestures to an artwork, or having the user imitate poses found in various works, which are then scored for accuracy.[37][38]

- The ArtLens Studio is a series of digital studios for visitors to make their own artwork, such as creating digital pottery by mimicking a potter's movements, or creating collages from images provided by the museum.[39]

- The ArtLens mobile application provides information about the museum and lists of all its artworks.[40] The app is able to communicate via Bluetooth to beacons located throughout the museum to determine the user's location, and allows the user to mark and save artworks they come across. The app connects to the previously mentioned ArtLens Exhibition and Wall, and was developed in cooperation with Navizon to create an innovative way to explore museums, by integrating real-time indoor location.[41]

Following the launch of ARTLENS, the Cleveland Museum of Art conducted a two-year study to see how the gallery impacts visitor engagement.[42][43] Surveys from November 2017 and January 2018 of 438 ARTLENS visitors found that 76% of viewers felt that the gallery "enhanced their overall museum experience"; 74% felt that it "encouraged them to look closely at art and notice new things"; and 73% said that it "increased their interest in the museum's collection."[43][44][42] Museum visitors born between 1981 and 1996 were 15% more likely to visit the gallery compared to older individuals.[43][42] The ARTLENS system also gathers analytical data; the time patrons spent looking at artworks went from an average of two-to-three seconds to fifteen seconds.[38]

Programs

[edit]The Cleveland Museum of Art also maintains a schedule of special exhibitions, lectures, films and musical programs. The department of performing arts, music and film hosts a film series[45] and the museum's Performing Arts Series,[46] which brings the creative energies of internationally renowned artists into Cleveland.

The department of education[47] at CMA creates programs for lifelong learning from lectures, talks and studio classes to outreach programs and community events, such as Parade the Circle",[48] Chalk Festival[49] and the "Winter Lights Lantern Festival".[50] Educational programs include distance learning,[51] "Art to Go",[52] and the "Educator's Academy".[53] The museum is also home to the Ingalls Library, one of the largest art museum libraries in the United States with over 500,000 volumes.[54]

Open Access collection materials

[edit]

In January 2019, the Cleveland Museum of Art announced that it was waiving its rights to "roughly 30,000 of the 61,328 objects in its permanent collection considered to be in the public domain".[55] They are using the Creative Commons – Zero license for high-resolution images and data about its collection.[56] Additionally, metadata for more than 61,000 pieces in its collection have been made available.[57] The Open Access material is available on a special section of the museum website.[58]

Governance

[edit]Attendance

[edit]The museum reported attendance of 597,715 during the period between July 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, the highest total in more than a decade.[59] In 2018, the museum had a record 769,435 visitors, replacing the previous record of 719,620 in 1987.[7]

Finance

[edit]In 1958, a $35-million bequest by industrialist Leonard C. Hanna Jr. vaulted the Cleveland Museum of Art into the ranks of the country's richest art museums.[60] Today, the museum receives operating support from the Ohio Arts Council through state tax dollars. It is also funded by Cuyahoga County residents through Cuyahoga Arts and Culture. The museum derives around two thirds of its $36 million budget from interest on its endowment, which was reported as $750 million in 2014.[61][62] The museum has an acquisition fund of $277 million, from which it draws about $13 million a year for purchase of works for its collections.[63]

Marketing

[edit]The museum has also taken an active role in presenting music concerts and lectures. These include performances by Chanticleer (ensemble), Roomful of Teeth, and John Luther Adams among others.

-

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Winter Lights Lantern Festival.

-

Noche Flamenca, part of CMA's VIVA! & Gala, now called the Performing Arts Series.[64]

Looted art

[edit]In 2003 a controversy arose over The Aviator, a painting by Fernand Leger which had been owned by the German Jewish art dealer Alfred Flechtheim, due to an unexplained Nazi-era provenance gap.[65][66][67] In 2013, the museum announced that it would pay the heirs of Arthur Feldmann in order to keep a drawing confiscated from him by the Nazis before they killed him in the Holocaust. The drawing was Allegory of Christian Faith, by the 17th century German artist Johann Liss[68] In 2017, the museum announced that it would return to Italy an ancient Roman marble portrait head of Drusus Minor stolen in 1944 from a provincial museum near Naples.[69] In August 2023, the Antiquities Trafficking Unit of the New York City District Attorney's office seized important ancient Roman bronze sculpture from the museum in connection with an investigation into looting and trafficking of ancient art at the site of the ancient Roman town of Bubon in Southwestern Turkey.[70] The museum then sued in the Federal District Court in Ohio to block the seizure, and while other looted works from other museums were returned to Turkey in December, the sculpture remained in the U.S. while the legal process continued.[71][72][73]

Directors

[edit]- William M. Griswold (2014–)[5]

- Fred Bidwell (2013–2014, interim director)[5]

- David Franklin (2010–2013)[74][5]

- Deborah Gribbon (2009–2010, interim director)

- Timothy Rub (2006–2009)[18]

- Katharine Lee Reid (2000–2006)[75]

- Kate Sellars (1999–2000, interim director)[75]

- Robert P. Bergman (1993–1999)[76]

- Evan H. Turner (1983–1993)[77]

- Sherman E. Lee (1958–1982)

- William M. Milliken (1930–1958)

- Frederic Allen Whiting (1913–1930)

In popular culture

[edit]The museum is the stand-in for the fictional S.H.I.E.L.D. headquarters in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and can be extensively seen in several office and establishing shots of the 2014 film Captain America: The Winter Soldier.[78] In several scenes, the museum's atrium can be seen as the "lobby" for the Washington, D.C.–based government organization. The outside of the museum and elevator tower are in other shots as well.

See also

[edit]- Landscape with a Windmill, 1646

- List of largest art museums

- List of most-visited art museums

- List of most-visited museums in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "About the Collection". Clevelandart.org. Retrieved November 16, 2024.

- ^ "The 100 most popular art museums in the world—blockbusters, bots and bounce-backs". theartnewspaper.com. The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ Steven Litt, The Plain Dealer (May 20, 2014). "William Griswold, director of the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, is named director of the Cleveland Museum of Art". cleveland.com. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "General Museum Information". Archived from the original on 2013-10-16. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ^ a b c d Steven Litt (26 March 2014). "After triumph and trauma, the Cleveland Museum of Art seeks committed, long-term leadership: CMA 2014". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum of Art Annual Report" (PDF). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Litt, Steven (January 15, 2019). "Cleveland Museum of Art hit record attendance in 2018, thanks to Kusama, FRONT and new programs". cleveland.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019.

- ^ "The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ "about – The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. 2002-09-28. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ "Hubbell and Benes". Architectureofcleveland.com. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Cleveland History:WADE, JEPTHA HOMER I". Ech.case.edu. 1997-07-23. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ a b c "the building project – The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Cleveland History:WADE, JEPTHA HOMER II". Ech.cwru.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ "National Register of Historical Places – OHIO (OH), Cuyahoga County". Nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ https://planning.clevelandohio.gov/dompdf/architectDomPrint.php?afil=437&archID=436

- ^ McGuigan, Cathleen (October 16, 2012). "Cleveland Museum of Art: Earning its Stripes: A Museum Builds on its Many Legacies". Architectural Record. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ Litt, Steven (December 26, 2013). "Rediscovering China, India and Southeast Asia at the Cleveland Museum of Art: The new West Wing". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Carol Vogel (January 6, 2006), Cleveland Museum Gets New Director The New York Times.

- ^ kmiers (18 December 2013). "Cleveland Museum of Art Celebrates Significant Accomplishments". Cleveland Museum of Art.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum of Art renovations beginning to see the light" Archived 2008-06-07 at the Wayback Machine, The Plain Dealer, March 29, 2008.

- ^ "calendar – The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Archived from the original on 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum of Art opens new Community Arts Center". WKYC. 11 June 2021.

- ^ "JAIC 1998, Volume 37, Number 2, Article 2 (pp. 173 to 186)". Aic.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ Doane, Randal (2020-04-15). ""Off the Ruling Class": Portraits by Hamell on Trial". Harper's Magazine. ISSN 0017-789X. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum Appoints Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi Curator of African Art – News – Art & Education". Art & Education. June 6, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "DIA's collection has national luster". The Detroit News. 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Cleveland Art Apollo". Clevelandart.org. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum of Art Presents Praxiteles: The Cleveland Apollo". 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ^ "2008 Stamps". USPS Postal News. US Postal Service. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009.

- ^ "Modern European Painting and Sculpture". Cleveland Museum of Art. 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ "European Painting and Sculpture". Cleveland Museum of Art. 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ "American Painting and Sculpture". Cleveland Museum of Art. 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ "Photography". Cleveland Museum of Art. 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ "Decorative Art and Design". Cleveland Museum of Art. 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ "History of the Ingalls Library and Museum Archives | Cleveland Museum of Art". Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ Usmani, Josh. "Cleveland Museum of Art's New ArtLens Gallery Will Give Visitors a More Interactive Experience". Cleveland Scene. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ a b c "ARTLENS Gallery". Cleveland Museum of Art. 2012-11-16. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ a b "The Cleveland Museum of Art Wants You To Play With Its Art". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ "ArtLens Studio". Cleveland Museum of Art. 2015-12-09. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ "ARTLENS". App Store. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ "Gallery One | Cleveland Museum of Art". www.clevelandart.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ a b c "The Cleveland Museum Studied How to Best Engage Visitors in the Age of Netflix. Here's What They Found". artnet News. 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ a b c Bolander, Elizabeth; Ridenour, Hannah; Quimby, Claire. "Art Museums and Technology: Developing New Metrics to Measure Visitor Engagement" (PDF). Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ Litt, Steven (2019-05-26). "CMA survey: Digital technology isn't just fun – it sharpens understanding of art". cleveland.com. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ "films – The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ^ "Music and Performances". Cleveland Museum of Art. 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Learn | Cleveland Museum of Art mobile site". Clevelandart.org. 28 November 2012. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Parade the Circle | The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Chalk Festival | The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Winter Lantern Lights Festival | The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Distance Learning | The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Archived from the original on 2014-06-30. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Art to Go | The Cleveland Museum of Art". Clevelandart.org. Archived from the original on 2014-06-30. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum of Art – Educators Academy". Archived from the original on June 19, 2010.

- ^ "Library". The Cleveland Museum of Art. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ^ Litt, Steven (January 23, 2019). "Cleveland Museum of Art launches next-generation open access to artworks and data online". cleveland.com. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

- ^ marmitage (2018-12-28). "Open Access at the Cleveland Museum of Art". Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum of Art Launches Open Access Collections Database". CODART. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ marmitage (28 December 2018). "Open Access at the Cleveland Museum of Art". Cleveland Museum of Art.

- ^ "Cleveland Museum of Art Reports Strong Gains in Attendance, Membership, Fundraising", Press release, The Cleveland Museum of Art.

- ^ Elaine Woo (July 20, 2008), "Cleveland art museum director gave it prestige", Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jason Edward Kaufman (January 8, 2009), How the richest US museums are weathering the storm, The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Carol Vogel (May 20, 2014), "Cleveland Hires Leader Of Morgan", The New York Times.

- ^ Judith H. Dobrzynski (March 14, 2012), "How an Acquisition Fund Burnishes Reputations", The New York Times.

- ^ "CMA Research Resources : The Thinker at the CMA". Clevelandart.org. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ Reporter, MARILYN H. KARFELDSenior Staff (2010-05-07). "Experts to discuss reclaiming Nazi-looted artworks". Cleveland Jewish News. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Steven Litt, cleveland com (2014-02-07). "World War II legacy: Artworks looted by Nazis and recovered by the Monuments Men now belong to the Cleveland Museum of Art". cleveland. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ "Museum links Leger's 'Aviator' to a German-Jewish art dealer who fled". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ "Cleveland art museum pays heirs for Nazi-confiscated drawing". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

Director David Franklin said the museum paid what he called "fair market value" to the heirs of Arthur Feldmann for the drawing "Allegory of Christian Faith," by the 17th century German artist Johann Liss, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported over the weekend. The museum purchased the drawing from London art dealer Herbert Bier in 1953, the museum said on its website. The Gestapo, or Nazi state secret police, confiscated Feldmann's collection of about 750 Old Master drawings. Feldmann died in 1941, two years after he was arrested by the Nazis in Brno, now in the Czech Republic, according to the museum. Feldman's wife died in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

- ^ Steven Litt, cleveland com (2017-04-18). "CMA returns stolen Roman portrait of Drusus to Italy". cleveland. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Steven Litt, cleveland com (2023-09-10). "Seizure of ancient sculpture at Cleveland Museum of Art signals a global shift over returning looted, contested artworks". cleveland. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Bowley, Graham; Mashberg, Tom (2023-10-19). "Cleveland Museum Sues to Block Seizure of Its 'Marcus Aurelius' Bronze". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "Cleveland Art Museum Initiates Rare Legal Challenge to Antiquities Seizure by Manhattan DA | Enforcement Edge | Blogs". Arnold & Porter. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Marlowe, Elizabeth (15 December 2023). "A Cleveland Museum's Bad Bet on a Looted Roman Statue". Hyperallergenic. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Steven Litt (August 27, 2010). "David Franklin of the National Gallery of Canada named director of the Cleveland Museum of Art". Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ a b Judith H. Dobrzynski (January 5, 2000), Museum Chief in Cleveland The New York Times.

- ^ William H. Honan (May 7, 1999), Robert P. Bergman, 53, Head Of Cleveland Museum of Art The New York Times.

- ^ Susan Heller Anderson (May 18, 1982), CLEVELAND MUSEUM CHOOSES DIRECTOR The New York Times.

- ^ "5 movies that were filmed in Cleveland". News 5 Cleveland WEWS. 2017-02-24. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

Further reading

[edit]- (in Japanese) 門脇 興次 (前クリーブランド日本語補習校(Japanese Language School of Cleveland)教諭・千葉県立成田市立東小学校教諭). "補習授業校における国際理解教育の実践 : クリーブランド美術館におけるジャパニーズフェスティバルを通して." 在外教育施設における指導実践記録 24, 111–114, 2001. Tokyo Gakugei University. See profile at CiNii.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- FRAME – The Cleveland Museum of Art is a member of FRAME (French Regional American Museum Exchange) and has presented and contributed to FRAME-sponsored exhibitions.

![Noche Flamenca, part of CMA's VIVA! & Gala, now called the Performing Arts Series.[64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/c/ca/NocheFlamenca.JPG/140px-NocheFlamenca.JPG)