| Colorado River toad | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Bufonidae |

| Genus: | Incilius |

| Species: | I. alvarius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Incilius alvarius (Girard, 1859)

| |

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The Colorado River toad (Incilius alvarius), also known as the Sonoran Desert toad, is a toad species found in northwestern Mexico and the southwestern United States. It is well known for its ability to exude toxins from glands within its skin that have psychoactive properties.

Description

[edit]The Colorado River toad can grow to about 190 millimetres (7.5 in) long and is the largest toad in the United States apart from the non-native cane toad (Rhinella marina). It has a smooth, leathery skin and is olive green or mottled brown in color. Just behind the large golden eye with horizontal pupil is a bulging kidney-shaped parotoid gland. Below this is a large circular pale green area which is the tympanum or ear drum. By the corner of the mouth there is a white wart and there are white glands on the legs. All these glands produce toxic secretions. Its call is described as, "a weak, low-pitched toot, lasting less than a second."[4]

Dogs (Canis familiaris) that have attacked toads have suffered paralysis or even death. Raccoons (Procyon lotor) have learned to pull a toad away from a pond by the back leg, turn it on its back and start feeding on its belly, a strategy that keeps the raccoon well away from the poison glands.[5] Unlike other vertebrates, this amphibian obtains water mostly by osmotic absorption across its abdomen. Toads in the family Bufonidae have a region of skin known as "the seat patch", which extends from mid abdomen to the hind legs and is specialized for rapid rehydration. Most of the rehydration is done through absorption of water from small pools or wet objects.[6]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

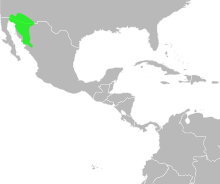

In the United States, the Colorado River toad is found in the lower Colorado River and the Gila River catchment areas, in extreme southwestern New Mexico and much of southern Arizona. It is considered possibly extirpated from California.[7] In Mexico, the toad is found in the states of Sonora, Sinaloa, and Chihuahua. It lives in both desert and semi-arid areas throughout its range. It is semiaquatic and is often found in streams, near springs, in canals and drainage ditches, and under water troughs.[5] The Colorado River toad is known to breed in artificial water bodies (e.g., flood control impoundments, reservoirs) and as a result, the distributions and breeding habitats of these species may have been recently altered in south-central Arizona.[8] It often makes its home in rodent burrows and is nocturnal.

Biology

[edit]The Colorado River toad is sympatric with the spadefoot toad (Scaphiopus spp.), Great Plains toad (Anaxyrus cognatus), red-spotted toad (Anaxyrus punctatus), and Woodhouse's toad (Anaxyrus woodhousei). Like many other toads, they are active foragers and feed on invertebrates, lizards, small mammals, and amphibians. The most active season for toads is May–September, due to greater rainfalls (needed for breeding purposes). The age of I. alvarius individuals in a population at Adobe Dam in Maricopa County, Arizona, ranged from 2 to 4 years; other species of toad have a lifespan of 4 to 5 years.[9] The taxonomic affinities of I. alvarius remain unclear, but immunologically, it is similarly close to the boreas and valliceps groups.[10]

Breeding

[edit]The breeding season starts in July, when the rainy season begins, and can last up to August. Normally, 1–3 days after the rain is when toads begin to lay eggs in ponds, slow-moving streams, temporary pools or man-made structures that hold water. Eggs are 1.6 mm in diameter, 5–7 mm apart, and encased in a long single tube of jelly with a loose but distinct outline. The female toad can lay up to 8,000 eggs.[11]

Psychotropic uses

[edit]The toad's primary defense system is glands that produce a poison that may be potent enough to kill a grown dog.[12] These parotoid glands also produce 5-methoxy-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT)[13] and bufotenin (which is named after the Bufo genus of toads); both of these chemicals belong to the family of hallucinogenic tryptamines. Bufotenin can be toxic.[14]

When vaporized, a single deep inhalation of the poison produces strong psychoactive effects within 15 seconds.[15] After inhalation, the user usually experiences a warm sensation, euphoria, and strong visual and auditory hallucinations, due to 5-MeO-DMT's high affinity for the 5-HT2 and 5-HT1A serotonin receptor subtypes.[16]

Bufotenin is a chemical constituent in the secretions and eggs of several species of toads belonging to the genus Bufo, but the Colorado River toad (Incillius alvarius) is the only toad species in which bufotenin is present in large enough quantities for a psychoactive effect. Extracts of toad secretion, containing bufotenin and other bioactive compounds, have been used in some traditional medicines such as ch’an su (probably derived from Bufo gargarizans), which has been used medicinally for centuries in China,[17] as a herbal remedy often illegally imported to the USA that can be prepared as a tea.[18]

The toad was "recurrently depicted in Mesoamerican art",[19] which some authors have interpreted as indicating that the effects of ingesting Bufo secretions have been known in Mesoamerica for many years; however, others doubt that this art provides sufficient ethnohistorical evidence to support the claim.[17]

In addition to bufotenin, Bufo secretions also contain digoxin-like cardiac glycosides, and ingestion of the poison can be fatal. Ingestion of Bufo toad toxins and eggs by humans has resulted in several reported cases of poisoning,[20][21][22] some of which resulted in death.[22][23][24] The first reported death associated with the ingestion of ch'an su was that of a young woman who consumed it as a prescribed (by a Chinese herbalist) Chinese herbal remedy mixed into a tea (an approximately 100ml bowl). Immediately upon ingesting the ch'an tea, the woman experienced vomiting, difficulty breathing, and gastric tenderness, which spurred her husband to take her to the emergency room, where she died two and a half hours after drinking the tea.[25]

Contemporary reports indicate that bufotenin-containing toad toxins have been used as a street drug; that is, as a supposed aphrodisiac,[26] ingested orally in the form of ch’an su,[22] and as a psychedelic, by smoking or orally ingesting Bufo toad secretion or dried Bufo skins. The use of chan'su and love stone (a related toad toxin preparation used as an aphrodisiac in the West Indies) has resulted in several cases of poisoning and at least one death.[22][27] The practice of orally ingesting toad secretions has been referred to in popular culture and in the scientific literature as "toad licking" and has drawn media attention.[28] Ken Nelson (under the pseudonym of Albert Most) published a booklet (illustrated by Gail Patterson) titled Bufo alvarius: The Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert[29][30][31] in 1983 which explained how to extract and smoke the secretions.

Among the notable people who have spoken publicly about their experiences with the psychoactive agents in the poison are boxer Mike Tyson,[32] comedian Chelsea Handler,[33] podcaster Joe Rogan,[34] television personality Christina Haack,[35] and motivational speaker Anthony Robbins.[36]

On October 31, 2022 the United States National Park Service posted a warning on Facebook that people should not handle or lick the toad.[37][38][39] Despite the warning's wide coverage in media, the post was made humorously and the Park Service has no records of people licking or otherwise harassing the toads in parks.[40]

U.S. state laws

[edit]

A substance found among the toxins the toad excretes when it is threatened, 5-MeO-DMT, is often dried into crystals and smoked. It is considered illegal in the United States, and categorized as a Schedule 1 substance, though law enforcement is increasingly less likely to enforce the laws with its growing popularity.[41]

The toads received national attention in 1994 after The New York Times Magazine published an article about a California teacher who became the first person to be arrested for possessing secretions of the toads.[42][43] Bufotenin had been outlawed in California since 1970.[44]

In November 2007, a man in Kansas City, Missouri, was discovered with an I. alvarius toad in his possession, and charged with possession of a controlled substance after they determined he intended to use its secretions for recreational purposes.[45][46] In Arizona, one may legally bag up to 10 toads with a fishing license, but it could constitute a criminal violation if it can be shown that one is in possession of this toad with the intent to smoke its secretions.[47]

None of the U.S. states in which I. alvarius is or was indigenous – California, Arizona, and New Mexico – legally allows a person to remove the toad from the state. For example, the Arizona Game and Fish Department is clear about the law in Arizona: "An individual shall not...export any live wildlife from the state; 3. Transport, possess, offer for sale, sell, sell as live bait, trade, give away, purchase, rent, lease, display, exhibit, propagate...within the state."[47]

Threatened species

[edit]Due to the rising popularity in collecting this toad, compounded with other threats such as motorists running over them, and predators such as raccoons eating them, U.S. states such as New Mexico and California have listed them as "threatened" and collecting I. alvarius is unlawful in those states.[48][49][50] Collecting these toads is thought to cause stress to them, in particular during the process of "milking" where collectors rub the toads under the chin to cause it to secrete the poison in the form of a milky substance that is then scraped from the body of the toad. Robert Villa, who serves as president of the Tucson Herpetological Society, said in a 2022 New York Times interview, "There’s a perception of abundance, but when you begin to remove large numbers of a species, their numbers are going to collapse like a house of cards at some point."[41]

Efforts to breed the toads in large quantities to offset their losses in the wild are criticized as potentially attracting predators to these areas, and creating a disease vector for pathogens such as chytrid fungus, which can then spread to devastate more of them in the wild. Synthetic forms of the drug that collectors seek in the toad poison are fairly easy to produce and may offset overcollection.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ Geoffrey Hammerson, Georgina Santos-Barrera. (2004). "Incilius alvarius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004: e.T54567A11152901. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2004.RLTS.T54567A11152901.en. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Frost, Darrel R. (2021). "Incilius alvarius (Girard, 1859)". Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.1. American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ National Audubon Society: Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians

- ^ a b Badger, David; Netherton, John (1995). Frogs. Shrewsbury, England: Swan Hill Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 1-85310-740-9.

- ^ Shibata, Yuki; Takeuchi, Hiro-aki; Hasegawa, Takahiro; Suzuki, Masakazu; Tanaka, Shigeyasu; Hillyard, Stanley D.; Nagai, Takatoshi (2011). "Localization of water channels in the skin of two species of desert toads, Anaxyrus (Bufo) punctatus and Incilius (Bufo) alvarius". Zoological Science. 28 (9): 664–670. doi:10.2108/zsj.28.664. PMID 21882955. S2CID 207287044.

- ^ "Sonoran Desert Toad - Incilius alvarius". www.californiaherps.com. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Gergus, Erik W. A.; Malmos, Keith B.; Sullivan, Brian K. (1999). "Natural hybridization among distantly related toads (Bufo alvarius, Bufo cognatus, Bufo woodhousii) in Central Arizona". Copeia. 1999 (2): 281–286. doi:10.2307/1447473. JSTOR 1447473.

- ^ "COLORADO RIVER TOAD (Bufo alvarius)". Species Accounts for the Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program (PDF). Boulder City, Nevada: Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program. September 2008. pp. 330–342.

- ^ Sullivan, Brian K.; Malmos, Keith B.; Movin, T. (1994). "Call variation in the Colorado River Toad (Bufo alvarius): behavioral and phylogenetic implications". Herpetologica. 50 (2): 146–156. doi:10.1007/BF00690963. JSTOR 3893021. PMID 3893021. S2CID 22694946.

- ^ Behler, J.L (1979). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Knopf; 1 edition (November 12, 1979). pp. 743. ISBN 0394508246.

- ^ Phillips, Steven J.; Wentworth Comus, Patricia, eds. (2000). A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. University of California Press. p. 537. ISBN 0-520-21980-5.

- ^ Erspamer, V.; Vitali, T.; Roseghini, M.; Cei, J.M. (July 1967). "5-Methoxy- and 5-Hydroxyindoles in the skin of Bufo alvarius" (PDF). Biochemical Pharmacology. 16 (7): 1149–1164. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(67)90147-5. PMID 6053590.

- ^ Repke DB, Torres CM (2006). Anadenanthera: visionary plant of ancient South America. New York: Haworth Herbal Press. ISBN 978-0-7890-2642-2.

- ^ Weil, Andrew T.; Davis, Wade (January 1994). "Bufo alvarius: a potent hallucinogen of animal origin". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 41 (1–2): 1–8. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(94)90051-5. PMID 8170151.

- ^ Krebs-Thomson, Kirsten; Ruiz, ErbertM.; Masten, Virginia; Buell, Mahalah; Geyer, MarkA. (December 2006). "The roles of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptors in the effects of 5-MeO-DMT on locomotor activity and prepulse inhibition in rats". Psychopharmacology. 189 (3): 319–329. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0566-1. PMID 17013638. S2CID 23396616.

- ^ a b Davis W, Weil A (1992). "Identity of a New World Psychoactive Toad". Ancient Mesoamerica. 3: 51–9. doi:10.1017/s0956536100002297. S2CID 162875250.

- ^ Ko, R. J.; Greenwald, M. S.; Loscutoff, S. M.; Au, A. M.; Appel, B. R.; Kreutzer, R. A.; Haddon, W. F.; Jackson, T. Y.; Boo, F. O.; Presicek, G. (1996). "Lethal Ingestion of Chinese Tea Containing Ch' an Su". The Western Journal of Medicine. 164 (1): 71–75. PMC 1303306. PMID 8779214.

- ^ Kennedy AB (1982). "Ecce Bufo: The Toad in Nature and in Olmec Iconography". Current Anthropology. 23 (3): 273–90. doi:10.1086/202831. S2CID 143698915.

- ^ Hitt M, Ettinger DD (1986). "Toad toxicity". N Engl J Med. 314 (23): 1517–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM198606053142320. PMID 3702971.

- ^ Ragonesi DL (1990). "The boy who was all hopped up". Contemporary Pediatrics. 7: 91–4.

- ^ a b c d Brubacher JR, Ravikumar PR, Bania T, Heller MB, Hoffman RS (1996). "Treatment of toad venom poisoning with digoxin-specific Fab fragments". Chest. 110 (5): 1282–8. doi:10.1378/chest.110.5.1282. PMID 8915235.

- ^ Gowda RM, Cohen RA, Khan IA (2003). "Toad venom poisoning: resemblance to digoxin toxicity and therapeutic implications". Heart. 89 (4): 14e–14. doi:10.1136/heart.89.4.e14. PMC 1769273. PMID 12639891.

- ^ Lever, Christopher (2001). The Cane Toad: The History and Ecology of a Successful Colonist. Westbury Academic & Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84103-006-7.

- ^ Ko, R. J.; Greenwald, M. S.; Loscutoff, S. M.; Au, A. M.; Appel, B. R.; Kreutzer, R. A.; Haddon, W. F.; Jackson, T. Y.; Boo, F. O.; Presicek, G. (1996). "Lethal Ingestion of Chinese Herbal Tea Containing Ch'an Su". The Western Journal of Medicine. 164 (1): 71–75. PMC 1303306. PMID 8779214.

- ^ Rodrigues, R.J. Aphrodisiacs through the Ages: The Discrepancy Between Lovers’ Aspirations and Their Desires. ehealthstrategies.com

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1995). "Deaths associated with a purported aphrodisiac—New York City, February 1993 – May 1995". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 44 (46): 853–5, 861. PMID 7476839.

- ^ The Dog Who Loved to Suck on Toads. NPR. Accessed on May 6, 2007.

- ^ Nelson, Ken. "Bufo avlarius: The Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert". Erowid. Illustrated by Gail Patterson. Erowid. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- ^ How ‘bout them toad suckers? Ain’t they clods? Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Smoky Mountain News. Accessed on May 6, 2007

- ^ Rodrigue, Daniel. "The Story Behind a 1984 Hallucinogenic Pamphlet From Denton Is Just as Trippy as Its Subject". Dallas Observer. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- ^ Gastelum, Andrew (17 November 2021). "Mike Tyson Says He 'Died' From Smoking Psychedelic Toad Venom". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Schmidt, Ingrid (10 February 2019). "Chelsea Handler Talks Cannabis Brand, Smoking Toad Venom, Marijuana Facials and More". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Romero, Simon (20 March 2022). "Demand for This Toad's Psychedelic Toxin Is Booming. Some Warn That's Bad for the Toad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ López, Canela (July 2021). "'Flip or Flop' star Christina Haack said smoking toad venom made her less egotistical and prepared her for a relationship". Insider. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Chubb, Hannah (12 July 2021). "Christina Haack Revealed She Smoked Psychedelic Toad Venom — But What Is It? A Doctor Explains". People Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "National Park Service issues unusual—but fun—warning about a toad". 7 November 2022.

- ^ "Well that's toad-ally terrifying…". Facebook.

- ^ Kim, Juliana (2022-11-06). "The National Park Service wants humans to stop licking this toad". NPR. Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- ^ Blevins, Jason (2022-11-18). "No, people aren't licking toads in national parks". The Colorado Sun. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ a b c Romero, Simon (2022-03-20). "Demand for This Toad's Psychedelic Toxin Is Booming. Some Warn That's Bad for the Toad". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ "Missionary for Toad Venom Is Facing Charges". The New York Times. 20 February 1994.

- ^ "Couple Avoid Jail In Toad Extract Case". The New York Times. 1 May 1994.

- ^ Bernheimer, Kate (2007). Brothers & beasts: an anthology of men on fairy tales. Wayne State University Press. pp. 157–159. ISBN 978-0-8143-3267-2.

- ^ "'Toad Smoking' Uses Venom From Angry Amphibian to Get High". FOX News. Kansas City. 3 December 2007.

- ^ Shelton, Natalie (7 November 2007). "Drug sweep yields weed, coke, toad". KC Community News. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007.

- ^ a b AZGFD.gov Archived 2008-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 19.33.6 NMAC Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. nmcpr.state.nm.us

- ^ 19.35.10 NMAC Archived 2012-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. nmcpr.state.nm.us

- ^ "Title 14. Division 1. Subdivision 1. Chapter 5., § 40(a)".

Further reading

[edit]- Frost, Darrel R.; Grant, Taran; Faivovich, JuliÁN; Bain, Raoul H.; Haas, Alexander; Haddad, CÉLIO F.B.; De SÁ, Rafael O.; Channing, Alan; Wilkinson, Mark; Donnellan, Stephen C.; Raxworthy, Christopher J.; Campbell, Jonathan A.; Blotto, Boris L.; Moler, Paul; Drewes, Robert C.; Nussbaum, Ronald A.; Lynch, John D.; Green, David M.; Wheeler, Ward C.; et al. (2006). "The Amphibian Tree of Life". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 297: 1–370. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2006)297[0001:TATOL]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86140137.

- Pauly, G. B.; Hillis, D. M.; Cannatella, D. C. (2004). "The history of a Nearctic colonization: Molecular phylogenetics and biogeography of the Nearctic toads (Bufo)". Evolution. 58 (11): 2517–2535. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00881.x. PMID 15612295. S2CID 10281132.