Comics journalism is a form of journalism that covers news or nonfiction events using the framework of comics, a combination of words and drawn images. Typically, sources are actual people featured in each story, and word balloons are actual quotes. The term "comics journalism" was coined by one of its most notable practitioners, Joe Sacco.[1] Other terms for the practice include "graphic journalism,"[2] "comic strip journalism", "cartoon journalism", "cartoon reporting",[3] "comics reportage",[4] "journalistic comics", "sequential reportage,"[5] and "sketchbook reports".[6]

Visual narrative storytelling has existed for thousands of years, but comics journalism brings reportage to the field in more direct ways. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists distinguished comics journalism from political cartoons this way:

"Editorial cartoons are quick, in-the-moment commentary, whose artists have to educate themselves on complex issues and craft well-informed opinions in a single take that emphasizes clarity under daily deadlines. Illustrated reporting, or comics journalism, takes days, weeks, or months to craft a story, which can run for pages, and which may or may not be presenting an opinion."[7]

The use of the comics medium to cover real-life events for news organizations, publications or publishers (in graphic novel format) is currently at an all-time peak.[citation needed] Comics journalism publications are active in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Italy, and India, and comics journalists also hail from such countries as Russia, Lebanon, Belgium, Peru, and Germany.[8] Many of the works are featured online and in collaboration with established publications, as well as the small press. In recent decades, works of comics journalism have appeared in such publications as Harper's Magazine, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Guardian, Slate, Columbia Journalism Review, and LA Weekly.

History

[edit]

Antecedents to comics journalism included printmakers like Currier and Ives, who illustrated American Civil War battles; political cartoonists like Thomas Nast; and George Luks, who was dubbed a "war artist" for his work from the front lines of the Spanish–American War.[9] Historically, pictorial representation (typically engravings) of news events were commonly used before the proliferation of photography in publications such as The Illustrated London News and Harper's Magazine.

In the 1920s, the political magazine New Masses sent cartoonists to cover strikes and labor battles, but they were restricted to single-panel cartoons.[9]

In the 1950s and the 1960s, Harvey Kurtzman did a number of true comics journalism pieces for magazines like Esquire and TV Guide.[9] In 1965, Robert Crumb, later a key founder of the underground comix movement, produced "Bulgaria: A Sketchbook Report" for Kurtzman's Help!, a tongue-in-cheek journalistic overview of the socialist country of Bulgaria, based on his own travels there.[10] Crumb had done an earlier, similar "sketchbook report" on Harlem, which was also published in Help![11] Kurtzman also hired Jack Davis and Arnold Roth to do light-hearted journalistic comics for Help![9]

Editor/cartoonist Leonard Rifas' two-issue series Corporate Crime Comics (Kitchen Sink Press, 1977, 1979) was an early example of comics reportage,[9] with a number of notable contributors, including Greg Irons, Trina Robbins, Harry Driggs, Guy Colwell, Kim Deitch, Justin Green, Jay Kinney, Denis Kitchen, and Larry Gonick.

Joe Sacco is widely considered to be one of the pioneers of the form,[12][13] starting with his 1991 series Palestine.[9] In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Sacco produced a number of works of comics journalism for such established publications as Details, Time, The New York Times Magazine, The Guardian, and Harper's Magazine. Since then, he has published a number of book-length works of comics journalism.

In October 1994 cartoonist Bill Griffith toured Cuba for two weeks, during a period of mass exodus, as thousands of Cubans took advantage of President Fidel Castro's decision to permit emigration for a limited time. In early 1995, Griffith published a six-week series of stories about Cuban culture and politics in his strip Zippy. The Cuba series included transcripts of conversations Griffith had conducted with various Cubans, including artists, government officials, and a Yoruba priestess.[14]

Cartoonist Art Spiegelman was comics editor of Details in the mid-1990s; in 1997 — modeling himself after Harvey Kurtzman — Spiegelman began assigning comics journalism pieces to a number of his cartoonist associates,[15] including Sacco, Peter Kuper, Ben Katchor, Peter Bagge, Charles Burns, Kaz, Kim Deitch, and Jay Lynch. The magazine published these works of journalism in comics form throughout 1998 and 1999, helping to legitimize the form in popular perception.[9]

Starting in 1998, and really intensely in the years 2000 to 2002, Peter Bagge did a number of comics journalism stories — on such topics as politics, the Miss America Pageant, bar culture, Christian rock, and the Oscars — mostly for Suck.com.

In the period 2000–2001, cartoonist Marisa Acocella Marchetto produced the semi-regular comics journalism strip The Strip for The New York Times, often on the topic of fashion.

Some of the first known magazines focused specifically on comics journalism include Mamma!, a magazine of comics journalism printed in Italy since 2009 and produced by a group of authors; and Symbolia, a digital magazine of comics journalism for tablet computers, which operated from 2013 to 2015.[16] Other digital magazines which focused on comics journalism during this period included Darryl Holliday & Erik Rodriguez' The Illustrated Press[17] and Josh Kramer's The Cartoon Picayune.

Jen Sorensen was editor of the "Graphic Culture" section of Splinter News (formerly Fusion) from 2014 to 2018, while Matt Bors edited the online comics collection The Nib from 2014[4] to 2023.[18] Both sites published comics journalism pieces.

In May 2016, The New York Times put comics journalism front-and-center for the first time with "Inside Death Row,"[19] by Patrick Chappatte (with Anne-Frédérique Widmann), a five-part series about the death penalty in the United States. In 2017, it published "Welcome to the New World,"[20] by Jake Halpern and Michael Sloan, chronicling a Syrian refugee family settling in the United States. The series ran in the print Sunday Review edition from January to September 2017 and won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning in 2018.[21]

In November 2019 the book Libia, about the war in Libya,[22] written by Francesca Mannocchi and drawn by Gianluca Costantini, was published in Italy;[23] it was translated and published in France in 2020.[24]

In 2022, in a sign of tacit approval of the form of comics journalism, the Pulitzer Prize committee changed the name of the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning (which had been in place since 1922) to the Pulitzer Prize for Illustrated Reporting and Commentary.[7][25] The 2022 award went to a work of comics journalism about the persecution of Uyghurs in China published by Insider.[7]

Techniques

[edit]As with traditional journalism, there are no rules per se about comics journalism, and there are a wide variety of practices. Some practitioners, like Joe Sacco and Susie Cagle, have a background in journalism, while others were trained first as cartoonists.[2] One feature that unites all forms of comics journalism is a reliance on witness interviews and other primary sources.[26] Many practitioners highlight the form's power to engender empathy in its subjects.[26]

Sacco is a trained journalist who extensively documents his subjects and spends years crafting his stories.[9] Among the techniques he uses to protect his subjects — who are often survivors of conflict zones in the Middle East and the former Yugoslavia — are to change their names and use his art to anonymize their faces.[9]

Wendy MacNaughton sketches extensively with her subjects and locations before retreating to her studio to craft the finished piece.[2]

Austrian graduate student Lukas Plank created a comic, "Drawn Truth: Transparency in Journalist Comics," based on his research into the field, that outlines some potential "best practices" for comics journalists.[27]

In a February 2005 article on comics journalism for Columbia Journalism Review, Kristian Williams introduced, explained, and defended comics journalism:

The ability to alternate between the realistic and the symbolic is a major strength of comics journalism. It is also one reason why editors are likely to shy away from it — or, as with the recent newspaper strips, to relegate comics journalism to cultural coverage and human-interest stories. When it comes to the front page, newspapers favor plain language, in part to protect the readers from the seductions of rhetoric, of art. And comics are irreducibly artistic.

But such reasoning also cuts the other way. The hard-nosed, facts-are-facts tone of "journalistic language" is also seductive. Plain-speaking is itself a kind of rhetoric, which wins trust precisely by seeming to leave rhetoric aside.

Art Spiegelman argues, "The phony objectivity that comes with a camera is a convention and a lie in the same way as writing in the third person rather than the first person. To write a comics journalism report you're already making an acknowledgment of biases and an urgency that communicates another level of information."[28]

Comics journalists

[edit]- Dan Archer[29]

- Peter Bagge

- Matt Bors[29]

- Steve Brodner

- Susie Cagle[29]

- Claudio Calia

- Patrick Chappatte

- Sue Coe[9]

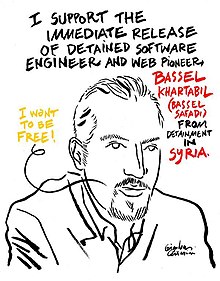

- Gianluca Costantini

- Sarah Glidden[26][29]

- Carlo Gubitosa

- Wendy MacNaughton[29]

- Marisa Acocella Marchetto

- Josh Neufeld

- Ted Rall

- Leonard Rifas[9]

- Joe Sacco[29]

- Orijit Sen

- Jen Sorensen

- Seth Tobocman[9]

- Sam Wallman

- Chip Zdarsky[9]

Magazines of comics journalism

[edit]Active

[edit]- Cartoon Movement, platform for works of graphic journalism and editorial cartoons

- Drawing the Times, international platform for graphic journalism

- La Revue Dessinée, French quarterly of comics journalism. Published since 2013 by Éditions du Seuil.[30]

- La Revue Dessinée Italia, the Italian version of the French magazine Le Revue Dessinée

Defunct

[edit]- The Cartoon Picayune, American anthology of comics journalism and nonfiction comics, published from 2011 to 2017. Founded and edited by Josh Kramer.[31]

- The Illustrated Press, Chicago-based outlet founded by Darryl Holliday.[32] Active from 2011 to 2015.[33]

- Mamma!, Italian printed magazine of comics journalism, editorial cartoons, data journalism, and photojournalism. Founded by Carlo Gubitosa and published by cultural association Altrinformazione from 2009 to 2013.[34]

- Symbolia, American digital magazine of comics journalism. Published from 2013 to 2015.[16]

- The Nib, American online non-fiction comics publication founded and operated by Matt Bors. Published under Medium from 2013 to 2015, under First Look Media from 2016[35] to 2019, and independently member-supported from 2019 to 2023. It is defunct as of September 2023.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Steinhauer, Jillian (quoting Hillary Chute). "The Outsider: Joe Sacco's comics journalism," The Nation (Dec. 28, 2020).

- ^ a b c Hodara, Susan. "Graphic Journalism," Communication Arts (March 2020).

- ^ Rhode, Mike (Dec 2006). "Cartoon reporting or comic strip journalism: An evolving genre's beginning bibliography". Comics Stuff #11. APA-I. No. 104.

- ^ a b Cavna, Michael (September 16, 2016). "Meet the man who's creating a space for longform journalism — in graphic novel form". COMICS. The Washington Post.

- ^ Rhode, Michael (March 2000). "Sequential Reportage [letter]". The Comics Journal. No. 221.

- ^ "SPIEGELMAN SPEAKS: Art Spiegelman is the author of Maus for which he won a special Pulitzer in 1992. Kathleen McGee interviewed him when he visited Minneapolis in 1998". Conduit. Interviewed by Kathleen McGee. 1998.

- ^ a b c Tornoe, Rob (May 1, 2022). "Pulitzer change leaves illustrators feeling slighted: New category muddies distinctions between illustrated reporting and editorial cartooning". Editor & Publisher.

- ^ Thorne, Laura. Reporting, Illustrated," Columbia Journalism Review (Summer 2019).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mackay, Brad (Jan 2008). "Behind the rise of investigative cartooning". Ad Astra Comix. This Magazine.

- ^ Crumb, Robert (July 1965). "Bulgaria: A Sketchbook Report". Help!. No. 25. Retrieved April 3, 2019 – via Transverse Alchemy.

- ^ Crumb, Robert (Jan 1965). "Harlem: A Sketchbook Report". Help!. No. 22.

- ^ Nalvic (June 12, 2012). "A Quick Guide to Comic Journalism". Nalvic's Reviews.

- ^ Crumm, David (June 29, 2012). "Joe Sacco nails down comic credentials in Journalism: Sacco contributes to new global language". Read the Spirit. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13.

- ^ "About Bill Griffith". Current Biography. 2001. Retrieved Dec 11, 2019 – via Zippy the Pinhead official Website.

- ^ "Details Begins Cartoon Journalism Features". The Comics Journal. No. 205. June 1998. p. 27.

- ^ a b "Symbolia digital magazine draws in readers with 'illustrated journalism'". Poynter.org. 3 December 2012.

- ^ "Illustrated Press | "Reporter Darryl Holliday and illustrator Erik Rodriguez are Chicago's pioneers of the comics journalism medium". Chicago. Archived from the original on 2018-07-15. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Bors, Matt (30 August 2023). "The End of The Nib". Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "Inside Death Row". The New York Times. May 2016.

- ^ "Welcome to the New World". The New York Times. September 2017.

- ^ Ayres, Andrea (April 19, 2018). "How a Graphic Novel "Welcome to the New World" Won a Pulitzer". The Beat.

- ^ "Libia". ChannelDraw. 28 October 2019. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ "Representing conflict beyond the headlines: An excerpt of Libia, a graphic novel by Francesca Mannocchi and Gianluca Costantini". The Polis Project, Inc. 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ "Libye | Rackham" (in French). Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Degg, D. D. (June 7, 2022). "Editor & Publisher Reports on Pulitzer Prize's New Illustrated Reporting and Commentary Category". The Daily Cartoonist.

- ^ a b c H.G. "In the frame: The power of comics journalism: The medium is able to narrate personal experiences more effectively than traditional journalism can" The Economist (Oct 21st 2016).

- ^ Plank, Lukas. "Drawn Truth". Drawn Truth (Tumblr). Archived from the original on Aug 29, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Williams, Kristian (Feb 2005). "The Case for Comics Journalism: Artist-reporters leap tall conventions in a single bound". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on Mar 10, 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f Polgreen, Erin. "What is Graphic Journalism?", The Hooded Utilitarian (Mar. 29, 2011).

- ^ "La Revue Dessinée, c'est quoi ?". Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ Clough, Rob (Oct 29, 2011). "The Comics Journalism of Josh Kramer". High-Low.

- ^ Kaneya, Rui (Sep 19, 2014). "How comics journalism brings stories to life: Chicago's Illustrated Press is at the forefront of a burgeoning movement". Columbia Journalism Review.

- ^ "Darryl Holliday". LinkedIn. Retrieved Jan 23, 2022.

- ^ "Focus sulla rivista Mamma! La nuova frontiera del giornalismo a fumetti". Il nuovo Corriere di Lucca e Versilia (in Italian). 30 October 2010.

- ^ "Matt Bors Brings the Nib to First Look Media". First Look Media. Feb 10, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ The Nib (2023-05-22). "The Future of The Nib". The Nib. Retrieved 2023-09-22.

Further reading

[edit]- Archer, Dan (Aug 19, 2011). "An introduction to comics journalism, in the form of comics journalism". Poynter Institute. Archived from the original on Sep 8, 2014.

- Bake, Julika; Zöhrer, Michaela (2017). "Telling the Stories of Others: Claims of Authenticity in Human Rights Reporting and Comics Journalism". Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding. 11 (1): 81–97. doi:10.1080/17502977.2016.1272903.

- Butler, Kirstin (Aug 2011). "Comic Books as Journalism: 10 Masterpieces of Graphic Nonfiction". The Atlantic.

- Duncan, Randy; Taylor, Michael Ray; Stoddard, David, eds. (2015). Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415730075.

- Embury, Gary; Minichiello, Mario (2018). Reportage Illustration: Visual Journalism. London: Bloomsbury.

- Gilbert, Jérémie; Keane, David (2015). "Graphic Reporting: Human Rights Violations through the Lens of Graphic Novels". In Giddens, Thomas (ed.). Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 236–254.

- Hare, Kristen (May 6, 2016). "A graphics journalism project from The New York Times is taking readers inside death row". Poynter.

- Kelp-Stebbins, Katherine; Saunders, Ben, eds. (2021). Art of the News: Comics Journalism. Eugene: Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art.

- Mirk, Sarah; Harris, Eleri (2024). Drawn from the Margins: The Power of Graphic Journalism. New York: Abrams ComicArts.

- Najarian, Jonathan (June 23, 2022). "Graphic depictions: Long-form comics as journalism". Quill.

- Orbán, Katalin (2015). "Mediating Distant Violence: Reports on Non-photographic Reporting in The Fixer and The Photographer". Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 6 (2): 122–137. doi:10.1080/21504857.2015.1027943. hdl:10831/62076.

- Pekar, Harvey (Fall 1987). "Comic Journalism". Harvey Sez. Weirdo. No. 21. — about Leonard Rifas and Educomics, and Joyce Brabner and Real War Stories

- Rhode, Mike (Dec 2006). "Cartoon reporting or comic strip journalism: An evolving genre's beginning bibliography". Comics Stuff #11. APA-I. No. 104.

- Weber, Wibke; Rall, Hans-Martin (2017). "Authenticity in Comics Journalism. Visual Strategies for Reporting Facts". Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 8 (4): 376–397. doi:10.1080/21504857.2017.1299020.

- Williams, Paul; Lyons, James, eds. (2010). The Rise of the American Comics Journalist. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

External links

[edit]- The Nib

- Cartoon Movement

- Drawing the Times

- La Revue Dessinée

- World Comics Network, grassroots nonfiction comics from around the world

- Positive Negatives, produces literary comics, animations, and podcasts about contemporary social and humanitarian issues

- Symbolia website (archived)