|

| Information mapping |

|---|

| Topics and fields |

| Node–link approaches |

|

| See also |

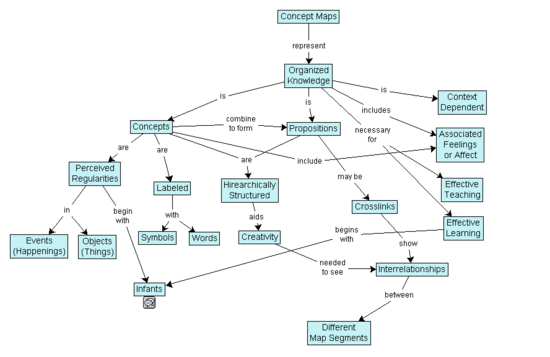

A concept map or conceptual diagram is a diagram that depicts suggested relationships between concepts.[1] Concept maps may be used by instructional designers, engineers, technical writers, and others to organize and structure knowledge.

A concept map typically represents ideas and information as boxes or circles, which it connects with labeled arrows, often in a downward-branching hierarchical structure but also in free-form maps.[2][3] The relationship between concepts can be articulated in linking phrases such as "causes", "requires", "such as" or "contributes to".[4]

The technique for visualizing these relationships among different concepts is called concept mapping. Concept maps have been used to define the ontology of computer systems, for example with the object-role modeling or Unified Modeling Language formalism.

Differences from other visualizations

[edit]- Topic maps: Both concept maps and topic maps are kinds of knowledge graph, but topic maps were developed by information management professionals for semantic interoperability of data (originally for book indices), whereas concept maps were developed by education professionals to support people's learning.[5] In the words of concept-map researchers Joseph D. Novak and Bob Gowin, their approach to concept mapping is based on a "learning theory that focuses on concept and propositional learning as the basis on which individuals construct their own idiosyncratic meanings".[6]

- Mind maps: Both concept maps and topic maps can be contrasted with mind mapping, which is restricted to a tree structure.[2] Concept maps can be more free-form,[3] as multiple hubs and clusters can be created, unlike mind maps, which emerge from a single center.[2]

History

[edit]Concept mapping was developed by the professor of education Joseph D. Novak and his research team at Cornell University in the 1970s as a means of representing the emerging science knowledge of students.[7] It has subsequently been used as a way to increase meaningful learning in the sciences and other subjects as well as to represent the expert knowledge of individuals and teams in education, government and business. Concept maps have their origin in the learning movement called constructivism. In particular, constructivists hold that learners actively construct knowledge.

Novak's work is based on the cognitive theories of David Ausubel, who stressed the importance of prior knowledge in being able to learn (or assimilate) new concepts: "The most important single factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows. Ascertain this and teach accordingly."[8] Novak taught students as young as six years old to make concept maps to represent their response to focus questions such as "What is water?" "What causes the seasons?" In his book Learning How to Learn, Novak stated that a "meaningful learning involves the assimilation of new concepts and propositions into existing cognitive structures."

Various attempts have been made to conceptualize the process of creating concept maps.[9] McAleese suggested that the process of making knowledge explicit, using nodes and relationships, allows the individual to become aware of what they know and as a result to be able to modify what they know.[10] Maria Birbili applied the same idea to helping young children learn to think about what they know.[11] McAleese's concept of the knowledge arena suggests a virtual space where learners may explore what they know and what they do not know.[10]

Use

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

Concept maps are used to stimulate the generation of ideas, and are believed to aid creativity.[4] Concept mapping is also sometimes used for brain-storming. Although they are often personalized and idiosyncratic, concept maps can be used to communicate complex ideas.

Formalized concept maps are used in software design, where a common usage is Unified Modeling Language diagramming amongst similar conventions and development methodologies.

Concept mapping can also be seen as a first step in ontology-building, and can also be used flexibly to represent formal argument — similar to argument maps.

Concept maps are widely used in education and business. Uses include:

- Note taking and summarizing gleaning key concepts, their relationships and hierarchy from documents and source materials

- New knowledge creation: e.g., transforming tacit knowledge into an organizational resource, mapping team knowledge

- Institutional knowledge preservation (retention), e.g., eliciting and mapping expert knowledge of employees prior to retirement

- Collaborative knowledge modeling and the transfer of expert knowledge

- Facilitating the creation of shared vision and shared understanding within a team or organization

- Instructional design: concept maps used as Ausubelian "advance organizers" that provide an initial conceptual frame for subsequent information and learning.

- Training: concept maps used as Ausubelian "advanced organizers" to represent the training context and its relationship to their jobs, to the organization's strategic objectives, to training goals.

- Communicating complex ideas and arguments

- Examining the symmetry of complex ideas and arguments and associated terminology

- Detailing the entire structure of an idea, train of thought, or line of argument (with the specific goal of exposing faults, errors, or gaps in one's own reasoning) for the scrutiny of others.

- Enhancing metacognition (learning to learn, and thinking about knowledge)

- Improving language ability

- Assessing learner understanding of learning objectives, concepts, and the relationship among those concepts[12]

- Lexicon development

See also

[edit]- CmapTools – Software for concept mapping

- Concept inventory – Knowledge assessment tool

- Conceptual framework – Method of organizing information

- Semantic network – Knowledge base that represents semantic relations between concepts in a network

- Level of measurement – Distinction between nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio variables

- Group concept mapping – Method of organizing groups of related concepts

- Information model – Software engineering visualization

- Idea networking – Method of cluster analysis

- List of concept- and mind-mapping software

- Nomological network – Representation of concepts and relationships between concepts

- Personal knowledge base – Knowledge management software

References

[edit]- ^ Peter J. Hager, Nancy C. Corbin. Designing & Delivering: Scientific, Technical, and Managerial Presentations, 1997, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Lanzing, Jan (January 1998). "Concept mapping: tools for echoing the minds eye". Journal of Visual Literacy. 18 (1): 1–14 (4). doi:10.1080/23796529.1998.11674524.

Although Novak originally started with the idea of hierarchical tree-shaped concept maps. This idea is not continued by the followers of Novak's technique or has either been dropped altogether. ... The difference between concept maps and mind maps is that a mind map has only one main concept, while a concept map may have several. This means that a mind map can be represented in a hierarchical tree structure.

- ^ a b Romance, Nancy R.; Vitale, Michael R. (Spring 1999). "Concept mapping as a tool for learning: broadening the framework for student-centered instruction". College Teaching. 47 (2): 74–79 (78). doi:10.1080/87567559909595789. JSTOR 27558942.

Shavelson et al. (1994) identified a number of variations of the general technique presented here for developing concept maps. These include whether (1) the map is hierarchical or free-form in nature, (2) the concepts are provided with or determined by the learner, (3) the students are provided with or develop their own structure for the map, (4) there is a limit on the number of lines connecting concepts, and (5) the connecting links must result in the formation of a complete sentence between two nodes.

- ^ a b Novak, Joseph D.; Cañas, Alberto J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them (Technical report). Pensacola, FL: Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. 2006-01 Rev 2008-01. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Garrido, Piedad; Tramullas, Jesús (September 2004). "Topic maps: an alternative or a complement to concept maps?" (PDF). In Cañas, Alberto J.; Novak, Joseph D.; González García, Fermín María (eds.). Concept maps: theory, methodology, technology: proceedings of the first International Conference on Concept Mapping, CMC 2004, Pamplona, Spain, Sept 14–17, 2004. Pamplona: Dirección de Publicaciones de la Universidad Pública de Navarra. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.469.1803. ISBN 9788497690669. OCLC 433188714.

- ^ Novak & Gowin 1984, p. 7.

- ^ "Joseph D. Novak". Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC). Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- ^ Ausubel, D. (1968). Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York.

- ^ Al-Kunifed, Ali; Wandersee, James H. (1990). "One hundred references related to concept mapping", Journal of Research in Science Teaching', 27: 1069–75.

- ^ a b McAleese, R. (1998). "The knowledge arena as an extension to the concept map: reflection in action", Interactive Learning Environments, 6(3), p.251–272.

- ^ Birbili, M. (2006). "Mapping knowledge: concept maps in early childhood education" Archived 2010-09-14 at the Wayback Machine, Early Childhood Research & Practice, 8(2), Fall 2006.

- ^ Mazany, Terry. "Science Framework for the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress" (PDF). Retrieved 1 November 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Novak, J.D. (2009) [1998]. Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge: Concept Maps as Facilitative Tools in Schools and Corporations (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9780415991858.

- Novak, J.D.; Gowin, D.B. (1984). Learning How to Learn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521319263.

- Moon, B.M.; Hoffman, R.R.; Novak, J.D.; Cañas, A.J. (2011). Applied Concept Mapping: Capturing, Analyzing, and Organizing Knowledge (1st ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 9781439828601.

External links

[edit]- Example of a concept map from 1957 by Walt Disney.