This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

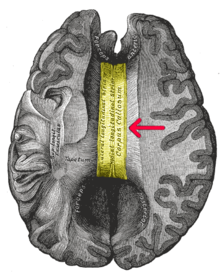

A corpus callosotomy (/kəˈlɔːs(ə)təmiː/) is a palliative surgical procedure for the treatment of medically refractory epilepsy.[1] The procedure was first performed in 1940 by William P. van Wagenen.[2] In this procedure, the corpus callosum is cut through, in an effort to limit the spread of epileptic activity between the two halves of the brain.[1] Another method to treat epilepsy is vagus nerve stimulation.[3]

Although the corpus callosum is the largest white matter tract connecting the hemispheres, some limited interhemispheric communication is still possible via the anterior and posterior commissures.[4] After the operation, however, the brain often struggles to send messages between hemispheres, which can lead to side effects such as speech irregularities, disconnection syndrome, and alien hand syndrome.

History

[edit]The first instances of corpus callosotomy were performed in the 1940s by William P. van Wagenen, who co-founded and served as president of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Attempting to treat epilepsy, van Wagenen studied and published the results of his surgeries, including the split-brain outcomes for patients. Most of the surgeries involved a partial division of the corpus callosum and resulted in improvements of seizure control in all patients.[2] Wagenen's work preceded the 1981 Nobel Prize-winning research of Roger W. Sperry by two decades. Sperry studied patients who had undergone corpus callosotomy and detailed their resulting split-brain characteristics.[2]

Improvements to surgical techniques, along with refinements of the indications, have allowed van Wagenen's procedure to endure; corpus callosotomy is still commonly performed throughout the world.[5] The surgery is a palliative treatment method for many forms of epilepsy, including atonic seizures, generalized seizures, and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.[6] In a 2011 study of children with intractable epilepsy accompanied by attention deficit disorder, EEG showed an improvement to both seizures and attention impairments following corpus callosotomy.[7]

Typical procedure

[edit]Prior to surgery, the patient's head must be partially or completely shaven. Once under general anesthesia, an incision will allow for a craniotomy to be performed. Then sectioning will occur between the two hemispheres of the brain. For a partial callosotomy, the anterior two-thirds of the corpus callosum are sectioned, and for a complete callosotomy, the posterior one-third is also sectioned. Afterward, the dura is closed and the portion of cranium is replaced. The scalp is then closed with sutures.[8] Endoscopic corpus callosotomy has been employed with blood loss minimized during the surgical procedure.[9]

Indications

[edit]Corpus callosotomy is intended to treat patients who have epilepsy and the resultant chronic seizures. The diminished life expectancy associated with epilepsy has been documented by population-based studies in Europe. In the UK and Sweden, the relative mortality rate of epileptic patients (patients whose epilepsy was not under control from medical or other surgical therapies and who continued to have the disease) increased two- and threefold, respectively. In the vast majority of cases, corpus callosotomy abolishes instance of seizures in the patient.[10]

Contraindications

[edit]Although it varies from patient to patient, a progressive neurological or medical disease might be an absolute or relative contraindication to corpus callosotomy. Intellectual disability is not a contraindication to corpus callosotomy. In a study of children with a severe intellectual disability, total callosotomy was performed with highly favorable results and insignificant morbidity.[11]

Neuroanatomical background

[edit]Corpus callosum anatomy and function

[edit]The corpus callosum is a fiber bundle of about 300 million fibers in the human brain that connects the two cerebral hemispheres. Its interhemispheric functions include the integration of perceptual, cognitive, learned, and volitional information.[12]

Role in epileptic seizures

[edit]The role of the corpus callosum in epilepsy is the interhemispheric transmission of epileptiform discharges. These discharges are generally bilaterally synchronous in preoperative patients. In addition to disrupting this synchrony, corpus callosotomy decreases the frequency and amplitude of the epileptiform discharges, suggesting the transhemispheric facilitation of seizure mechanisms.[13]

Drawbacks

[edit]Side effects

[edit]The most prominent non-surgical complications of corpus callosotomy relate to speech irregularities. For some patients, sectioning may be followed by a brief spell of mutism. A long-term side effect may be an inability to engage in spontaneous speech. In addition, the resultant split-brain prevents some patients from following verbal commands that require the use of their non-dominant hand.[14]

Disconnection syndrome is another well-known side effect of the surgery.[15] This occurs due to the brain's inability to transfer information between the hemispheres.[16] One characteristic symptom is the "crossed-avoiding reaction", which is observed when one hemisphere does not respond to visual or sensory (e.g., touch, pressure, or pain) stimuli presented to the opposite side.

For instance, when an object is shown in the patient's right visual field, the left hemisphere (typically language-dominant) processes this information, allowing the patient to name the object easily. However, if the same object is shown in the left visual field, the right hemisphere perceives it, but the information does not transfer to the left (verbal) hemisphere.[17] Consequently, while the patient cannot verbally identify the object, they are still able to select it with their left hand.[17]

Another complication is alien hand syndrome, in which the affected person's hand appears to take on a mind of its own.[18] In one described incident, the patient grabbed their throat with their left hand and struggled to remove, as they had no control over it.[19]

Cognitive impairments may also be seen.[20] Other symptoms may occur after the operation but generally go away on their own, such as scalp numbness, feeling tired or depressed, headaches, and difficulty speaking, remembering things, or finding words.[21]

Alternatives

[edit]Epilepsy is also treated by a less invasive process called vagus nerve stimulation. This method utilizes an electrode implanted around the left vagus nerve within the carotid sheath in order to send electrical impulses to the nucleus of the solitary tract.[3] However, corpus callosotomy has been proven to offer significantly better chances of seizure freedom compared with vagus nerve stimulation (58.0% versus 21.1% reduction in atonic seizures, respectively).[22]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mathews, Marlon S.; Linskey, Mark E.; Binder, Devin K. (29 February 2008). "William P. van Wagenen and the first corpus callosotomies for epilepsy". Journal of Neurosurgery. 108 (3): 608–613. doi:10.3171/JNS/2008/108/3/0608. ISSN 0022-3085. PMID 18312112. S2CID 6007475.

- ^ a b c Mathews, Marlon S.; Linskey, Mark E.; Binder, Devin K. (2008). "William P. Van Wagenen and the first corpus callosotomies for epilepsy". Journal of Neurosurgery. 108 (3): 608–613. doi:10.3171/JNS/2008/108/3/0608. PMID 18312112. S2CID 6007475.

- ^ a b Abd-El-Barr, Muhammad M.; Joseph, Jacob R.; Schultz, Rebecca; Edmonds, Joseph L.; Wilfong, Angus A.; Yoshor, Daniel (2010). "Vagus nerve stimulation for drop attacks in a pediatric population". Epilepsy & Behavior. 19 (3): 394–9. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.06.044. PMID 20800554. S2CID 13346234.

- ^ Gazzaniga, M. S. (1 July 2000). "Cerebral specialization and interhemispheric communication: Does the corpus callosum enable the human condition?". Brain. 123 (7): 1293–1326. doi:10.1093/brain/123.7.1293. PMID 10869045.

- ^ Markosian, Christopher; Patel, Saarang; Kosach, Sviatoslav; Goodman, Robert R.; Tomycz, Luke D. (1 March 2022). "Corpus Callosotomy in the Modern Era: Origins, Efficacy, Technical Variations, Complications, and Indications". World Neurosurgery. 159: 146–155. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2022.01.037. ISSN 1878-8750.

- ^ Schaller, Karl (2012). "Corpus Callosotomy: What is New and What is Relevant?". World Neurosurgery. 77 (2): 304–305. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2011.07.026. PMID 22120324.

- ^ Yonekawa, Takahiro; Nakagawa, Eiji; Takeshita, Eri; et al. (2011). "Effect of corpus callosotomy on attention deficit and behavioral problems in pediatric patients with intractable epilepsy". Epilepsy & Behavior. 22 (4): 697–704. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.08.027. PMID 21978470. S2CID 34733721.

- ^ Reeves, Alexander G.; Roberts, David W., eds. (1995). Epilepsy and the Corpus Callosum. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-45134-8.[page needed]

- ^ Sood S, Marupudi NI, Asano E, Haridas A, Ham SD (2015). "Endoscopic corpus callosotomy and hemispherotomy". J Neurosurg Pediatr. 16 (6): 681–6. doi:10.3171/2015.5.PEDS1531. PMID 26407094.

- ^ Sperling, Michael R.; Feldman, Harold; Kinman, Judith; Liporace, Joyce D.; O'Connor, Michael J. (1999). "Seizure control and mortality in epilepsy". Annals of Neurology. 46 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(199907)46:1<45::AID-ANA8>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 10401779. S2CID 20595932.

- ^ Asadi-Pooya, Ali A.; Sharan, Ashwini; Nei, Maromi; Sperling, Michael R. (2008). "Corpus callosotomy". Epilepsy & Behavior. 13 (2): 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.04.020. PMID 18539083. S2CID 19256444.

- ^ Hofer, Sabine; Frahm, Jens (2006). "Topography of the human corpus callosum revisited—Comprehensive fiber tractography using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging". NeuroImage. 32 (3): 989–94. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.044. PMID 16854598. S2CID 1164423.

- ^ Matsuo, Atsuko; Ono, Tomonori; Baba, Hiroshi; Ono, Kenji (2003). "Callosal role in generation of epileptiform discharges: Quantitative analysis of EEGs recorded in patients undergoing corpus callosotomy". Clinical Neurophysiology. 114 (11): 2165–71. doi:10.1016/S1388-2457(03)00234-7. PMID 14580615. S2CID 10604808.

- ^ Andersen, Birgit; Árogvi-Hansen, Bjarke; Kruse-Larsen, Christian; Dam, Mogens (1996). "Corpus callosotomy: Seizure and psychosocial outcome a 39-month follow-up of 20 patients". Epilepsy Research. 23 (1): 77–85. doi:10.1016/0920-1211(95)00052-6. PMID 8925805. S2CID 19538184.

- ^ Stigsdotter-Broman, Lina; Olsson, Ingrid; Flink, Roland; Rydenhag, Bertil; Malmgren, Kristina (February 2014). "Long-term follow-up after callosotomy—A prospective, population based, observational study". Epilepsia. 55 (2): 316–321. doi:10.1111/epi.12488. ISSN 0013-9580. PMC 4165268. PMID 24372273.

- ^ Lechevalier, B.; Andersson, J. C.; Morin, P. (1 May 1977). "Hemispheric disconnection syndrome with a "crossed avoiding" reaction in a case of Marchiafava-Bignami disease". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 40 (5): 483–497. doi:10.1136/jnnp.40.5.483. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 492724. PMID 894319.

- ^ a b de Haan, Edward H. F.; Corballis, Paul M.; Hillyard, Steven A.; Marzi, Carlo A.; Seth, Anil; Lamme, Victor A. F.; Volz, Lukas; Fabri, Mara; Schechter, Elizabeth; Bayne, Tim; Corballis, Michael; Pinto, Yair (2020). "Split-Brain: What We Know Now and Why This Is Important for Understanding Consciousness". Neuropsychology Review. 30 (2): 224–233. doi:10.1007/s11065-020-09439-3. ISSN 1040-7308. PMC 7305066. PMID 32399946.

- ^ Biran, Iftah; Giovannetti, Tania; Buxbaum, Laurel; Chatterjee, Anjan (1 June 2006). "The alien hand syndrome: What makes the alien hand alien?". Cognitive Neuropsychology. 23 (4): 563–582. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.537.6357. doi:10.1080/02643290500180282. ISSN 0264-3294. PMID 21049344. S2CID 15889976.

The alien hand syndrome is a deeply puzzling phenomenon in which brain-damaged patients experience their limb performing seemingly purposeful acts without their intention. Furthermore, the limb may interfere with the actions of their normal limb.

- ^ Hassan, Anhar; Josephs, Keith A. (17 June 2016). "Alien Hand Syndrome". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 16 (8): 73. doi:10.1007/s11910-016-0676-z. ISSN 1534-6293. PMID 27315251.

- ^ Huang, Xiaoqin; Du, Xiangnan; Song, Haiqing; Zhang, Qian; Jia, Jianping; Xiao, Tianyi; Wu, Jian (15 November 2015). "Cognitive impairments associated with corpus callosum infarction: a ten cases study". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 8 (11): 21991–21998. PMC 4724017. PMID 26885171.

- ^ "Corpus Callosotomy – Treatments – For Patients – UR Neurosurgery – University of Rochester Medical Center". urmc.rochester.edu.

- ^ Rolston, John D.; Englot, Dario J.; Wang, Doris D.; Garcia, Paul A.; Chang, Edward F. (October 2015). "Corpus callosotomy versus vagus nerve stimulation for atonic seizures and drop attacks: A systematic review". Epilepsy & Behavior. 51: 13–17. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.06.001. PMC 5261864. PMID 26247311.

Further reading

[edit]- Maxwell, Robert E. (6 August 2009). "Chapter 162 – Corpus Callosotomy". In Lozano, Andres M.; Gildenberg, Philip L.; Tasker, Ronald R. (eds.). Textbook of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery (2nd ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 2723–2740. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69960-6_162. ISBN 978-3-540-69959-0.

- Olivier, André; Boling, Warren W.; Tanriverdi, Taner (2012). "Callosotomy". Techniques in Epilepsy Surgery: The MNI Approach. Cambridge University Press. pp. 201–215. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139021951.018. ISBN 978-1-107-00749-9.

- Roberts, David W. (17 August 2009). "Chapter 74 – Corpus Callosotomy". In Shorvon, Simon; Perucca, Emilio; Engel Jr, Jerome (eds.). The Treatment of Epilepsy (3rd ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 943–950. doi:10.1002/9781444316667.ch74. ISBN 978-1-4051-8383-3.

- Sauerwein, Hannelore C.; Lassonde, Maryse; Revol, Olivier; Cyr, Francine; Geoffroy, Guy; Mercier, Claude (15 December 2001). "Chapter 26 – Neuropsychological and Psycho-social Consequences of Corpus Callosotomy". In Jambaqué, Isabelle; Lassonde, Maryse; Dulac, Olivier (eds.). Neuropsychology of Childhood Epilepsy. Advances in Behavioral Biology Series. Vol. 50. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 245–256. doi:10.1007/0-306-47612-6_26. ISBN 978-0-306-46522-2.

External links

[edit]- Details of procedure at epilepsy.com

- Encyclopedia of Surgery: Corpus callosotomy