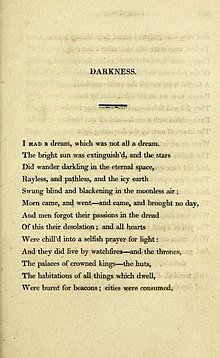

"Darkness" is a poem written by Lord Byron in July 1816 on the theme of an apocalyptic end of the world which was published as part of the 1816 The Prisoner of Chillon collection.

The year 1816 was known as the Year Without a Summer, because Mount Tambora had erupted in the Dutch East Indies the previous year, casting enough sulphur into the atmosphere to reduce global temperatures and cause abnormal weather across much of north-east America and northern Europe. This pall of darkness inspired Byron to write his poem.

Literary critics were initially content to classify it as a "last man" poem, telling the apocalyptic story of the last man on Earth. More recent critics have focused on the poem's historical context, as well as the anti-biblical nature of the poem, despite its many references to the Bible. The poem was written only months after the end of Byron's marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke.

Historical context

[edit]

Byron's poem was written during the Romantic period. During this period, several events occurred which resembled (to some) the biblical signs of the apocalypse. Many authors at the time saw themselves as prophets with a duty to warn others about their impending doom.[1] However, at the same time period, many were questioning their faith in a loving God, due to recent fossil discoveries revealing records of the deaths of entire species buried in the earth.[2]

1816, the year in which the poem was written, was called "the year without a summer", as strange weather and an inexplicable darkness caused record-cold temperatures, across Europe, especially in Geneva.[3] Byron claimed to have received his inspiration for the poem, saying he "wrote it... at Geneva, when there was a celebrated dark day, on which the fowls went to roost at noon, and the candles were lighted as at midnight".[4] The darkness was (unknown to those of the time) caused by the volcanic ash spewing from the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia.[5] The search for a cause of the strange changes in the light of day only grew as scientists discovered sunspots on the Sun so large that they could be seen with the naked eye.[5] Newspapers such as the London Chronicle reported on the panic:

The large spots which may now be seen upon the sun's disk have given rise to ridiculous apprehensions and absurd predictions. These spots are said to be the cause of the remarkable and wet weather we have had this Summer; and the increase of these spots is represented to announce a general removal of heat from the globe, the extinction of nature, and the end of the world.[5]

A scientist in Italy predicted that the Sun would go out on 18 July,[6] shortly before Byron's writing of "Darkness". His "prophecy" caused riots, suicides, and religious fervour all over Europe.[7] For example:

A Bath girl woke her aunt and shouted at her that the world was ending, and the woman promptly plunged into a coma. In Liege, a huge cloud in the shape of a mountain hovered over the town, causing alarm among the "old women" who expected the end of the world on the eighteenth. In Ghent, a regiment of cavalry passing through the town during a thunderstorm blew their trumpets, causing "three-fourths of the inhabitants" to rush forth and throw themselves on their knees in the streets, thinking they had heard the seventh trumpet.[7]

This prediction, and the strange behavior of nature at this time, stood in direct contrast with many of the feelings of the age. William Wordsworth often expresses in his writing a belief in the connection of God and nature which for much of the Romantic Era's poetry is typical. His "Tintern Abbey", for example, says "Nature never did betray / The heart that loved her".[8] His poetry also carries the idea that nature is a kind thing, living in peaceful co-existence with man. He says in the same poem, referring to nature, that "all which we behold / is full of blessings."[9] In other poems, such as "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud", he uses language for flowers and clouds that is commonly used for heavenly hosts of angels.[10] Even the more frightening Gothic poems of Coleridge, another famous poet of the time, argue for a kind treatment of nature that is only cruel if treated cruelly, as in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, unlike Byron's sun, which goes out with no human mistreatment mentioned at all.[9]

Criticism and analysis

[edit]In the past, critics classified "Darkness" as a "Last Man" poem, following a general theme of the end of the world scenes from the view of the last man on Earth. However, recent scholarship has pointed out the poem's lack of any single "Last Man" character.[11] At the conclusion of the poem, however, it is only the consciousness of the speaker that remains in a dark and desolate universe. Thus, the narrator could function as a Last Man character.

Biblical imagery

[edit]This article possibly contains original research. (February 2024) |

Byron also uses the hellish biblical language of the apocalypse to carry the real possibility of these events to his readers. The whole poem can be seen as a reference to Matthew 24:29: "the sun shall be darkened." In line 32 it describes men "gnash[ing] their teeth" at the sky, a clear biblical parallel of hell.[12] Vipers twine "themselves among the multitude, / Hissing."[13] Two men left alive of "an enormous city" gather "holy things" around an altar, "for an unholy usage"—to burn them for light. Seeing themselves in the light of the fire, they die at the horror of seeing each other "unknowing who he was upon whose brow Famine had written Fiend."[14] In this future, all men are made to look like fiends, emaciated, dying with "their bones as tombless as their flesh."[15] They also act like fiends, as Byron says: "no love was left,"[16] matching the biblical prophecy that at the end of the world, "the love of many shall wax cold."[17] In doing this, Byron is merely magnifying the events already occurring at the time. The riots, the suicides, the fear associated with the strange turn in the weather and the predicted destruction of the Sun, had besieged not only people's hope for a long life, but their beliefs about God's creation and about themselves as well. By bringing out this diabolical imagery, Byron is communicating that fear; that "Darkness [or nature] had no need / of aid from them—She was the universe."[18]

Byron's pessimistic views continue, as he mixes Biblical language with the apparent realities of science at the time. As Paley points out, it is not so much significant that Byron uses Biblical passages as that he deviates from them to make a point.[19] For example, the thousand-year peace mentioned in the book of Revelation as coming after all the horror of the apocalypse does not exist in Byron's "Darkness." Instead, "War, which for a moment was no more, / Did glut himself again."[20] In other words, swords are only beaten temporarily into plowshares, only to become swords of war once again. Also, the fact that the vipers are "stingless"[21] parallels the Biblical image of the peace to follow destruction: "And the sucking child shall play in the whole of the asp."[19] In the poem, though, the snake is rendered harmless, but the humans take advantage of this and the vipers are "slain for food." Paley continues, saying "associations of millennial imagery are consistently invoked to be bitterly frustrated."[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Greenblatt 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Gordon 2006, p. 614.

- ^ Paley 1995, p. 2.

- ^ Paley 1995, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Vail 1997, p. 184.

- ^ Vail 1997, p. 183.

- ^ a b Vail 1997, p. 186.

- ^ Wordsworth 2006, ll. 122–123.

- ^ a b Schroeder 1991, p. 116.

- ^ Gordon 2006, l. 4.

- ^ Schroeder 1991, p. 117.

- ^ see Matt 24:51

- ^ Gordon 2006, ll. 35–37.

- ^ Gordon 2006, ll. 55–69.

- ^ Gordon 2006, l. 45.

- ^ Gordon 2006, l. 41.

- ^ see Matt 24:12

- ^ Gordon 2006, ll. 81–82.

- ^ a b c Paley 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Gordon 2006, ll. 38–39.

- ^ Gordon 2006, l. 37.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gordon, George (2006). "Darkness". In Greenblatt, Stephen (ed.). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. D (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 614–16.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (2006). "Introduction". In Greenblatt, Stephen (ed.). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. D (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 1–22.

- Paley, Morton D. (1995). "Envisioning Lastness: Byron's 'Darkness,' Campbell's 'the Last Man,' and the Critical Aftermath". Romanticism: The Journal of Romantic Culture and Criticism. 1: 1–14. doi:10.3366/rom.1995.1.1.1.

- Schroeder, Ronald A. (1991). "Byron's 'Darkness' and the Romantic Dis-Spiriting of Nature.". In Shilstone, Frederick W. (ed.). Approaches to Teaching Byron's Poetry. New York: MLA. pp. 113–119.

- Vail, Jeffrey (1997). "'the Bright Sun was Extinguis'd': The Bologna Prophecy and Byron's 'Darkness'". Wordsworth Circle. 28: 183–192. doi:10.1086/TWC24043945. S2CID 165356110.

- Wordsworth, William (2006). "Lines: Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey". In Greenblatt, Stephen (ed.). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. D (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 258–62.

- — (2006a). "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud". In Greenblatt, Stephen (ed.). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. D (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 305–6.

External links

[edit] Darkness public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Darkness public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "Darkness" at Poetry Foundation

- "Darkness" at Wikisource