| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-Δ6a(10a)-THC, 1,2-dimethylheptyl-Δ3-THC, A-40824, EA-2233 |

| Drug class | Cannabinoid |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 20–39 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

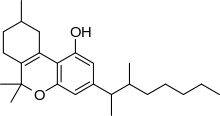

| Formula | C25H38O2 |

| Molar mass | 370.577 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Dimethylheptylpyran (DMHP) is a synthetic cannabinoid and analogue of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). It was invented in 1949 during attempts to elucidate the structure of Δ9-THC, one of the active components of cannabis.[2] DMHP is a pale yellow, viscous oil which is insoluble in water but dissolves in alcohol or non-polar solvents.

DMHP is similar in structure to THC, differing only in the position of one double bond, and the replacement of the 3-pentyl chain with a 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl) chain.[3]

Effects

[edit]DMPH produces similar activity to THC, such as sedative effects, but is considerably more potent,[4] especially having much stronger analgesic and anticonvulsant effects than THC, although comparatively weaker psychological effects.

Mechanism of action

[edit]It is thought to act as a CB1 receptor agonist, in a similar manner to other cannabinoid derivatives.[5][6] While DMHP itself has been subject to relatively little study since the characterization of the cannabinoid receptors, the structural isomer 1,2-dimethylheptyl-Δ8-THC has been shown to be a highly potent cannabinoid agonist, and the activity of its enantiomers has been studied separately.[7]

Chemistry

[edit]Isomerism

[edit]

| 7 double bond isomers of dimethylheptylpyran and their 120 stereoisomers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dibenzopyran numbering | Monoterpenoid numbering | Additional chiral centers on side chain | Number of stereoisomers | Natural occurrence | Convention on Psychotropic Substances Schedule | ||||

| Short name | Chiral centers in dibenzopyran backbone | Full name | Short name | Chiral centers in dibenzopyran backbone | 1,2-dimethylheptyl numbering | 3-methyloctan-2-yl numbering | |||

| Δ6a(7)-DMHP | 9 and 10a | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-8,9,10,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ4-DMHP | 1 and 3 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 3 | 16 | No | unscheduled |

| Δ7-DMHP | 6a, 9 and 10a | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-6a,9,10,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ5-DMHP | 1, 3 and 4 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 3 | 32 | No | unscheduled |

| Δ8-DMHP | 6a and 10a | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-6a,7,10,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ6-DMHP | 3 and 4 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 3 | 16 | No | unscheduled |

| Δ9,11-DMHP | 6a and 10a | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-6a,7,8,9,10,10a-hexahydro-6,6-dimethyl-9-methylene-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ1(7)-DMHP | 3 and 4 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 3 | 16 | No | unscheduled |

| Δ9-DMHP | 6a and 10a | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-6a,7,8,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ1-DMHP | 3 and 4 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 3 | 16 | No | unscheduled |

| Δ10-DMHP | 6a and 9 | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-6a,7,8,9-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ2-DMHP | 1 and 4 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 3 | 16 | No | unscheduled |

| Δ6a(10a)-DMHP | 9 | 3-(1,2-dimethylheptyl)-7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ3-DMHP | 1 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 3 | 8 | No | Schedule I |

Note that 6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol is the same as 6H-benzo[c]chromen-1-ol.

History

[edit]Edgewood Arsenal and EA-2233

[edit]The fiscal budgeting and planning for Edgewood Arsenal (established in 1948) considered it to be primarily a defensive research facility. The US military, at the time, knew that the USSR was spending 10 times more than the USA on chemical weapons development. Edgewood initially enjoyed a mandate[clarification needed] and lack of oversight. Edgewood Arsenal Chemical Corps was tasked with ensuring that America was prepared with adequate counter-tactics if needed and that it could mount its own psychochemical retaliatory strike against the USSR if necessary. Edgewood performed analysis and submitted data to military commanders who could then choose to incorporate that into their strategy. In practice, however, it was mostly to make the strategists aware of special weapons and tactics that the enemy could instead deploy.

The Edgewood Laboratory was originally founded in 1948. The original cannabinoid distillate (the precursor to EA-2233, called EA-1476 or "Red oil"), known today as delta-9-THC, was first created in 1949, and laboratory study of EA-1476 occurred in the mid-1950s. A single batch of EA-2233 was prepared by chemist Harry Pars of A.D. Little Labs in 1962 under a top-secret government contract. It was administered to groups of consenting & informed[citation needed] enlisted servicemen by Dr. James Ketchum in 1962. The Edgewood laboratory was shut down in 1975. Government funding for continued military development of synthetic cannabis was lacking and the cannabinoid research program was indefinitely suspended along with the rest of the Edgewood Arsenal experiments in the late 1970s for a variety of reasons. There was growing public distrust of the military and government, and there was little useful purpose for the further development of chemical incapacitating agents during and after the Vietnam era.[8]

Multiple newspapers criticized the EA-2233 experiments. Since the 1930s, cannabis and cannabinoids had consistently been seen by the public as dangerous and addictive drugs. DMHP was compared to BZ, a non-cannabis chemical that was cited to be useless among military planners, and was only tested once in a hastily constructed operation called "Project Dork" (part of Project 112).[9]

Research

[edit]Imvestigation as non-lethal incapacitating agent

[edit]DMHP and its O-acetate ester were extensively investigated by the US military chemical weapons program in the Edgewood Arsenal experiments, as possible non-lethal incapacitating agents.[10]

DMHP has three stereocenters and consequently has eight possible stereoisomers, which differ considerably in potency. The mixture of all eight isomers of the O-acetyl ester was given the code number EA-2233, with the eight individual isomers numbered EA-2233-1 through EA-2233-8. The most potent isomer is EA-2233-2, with an active dose range in humans of 0.5–2.8 μg/kg (i.e. ~35–200 μg for a 70 kg adult). Active doses varied markedly between individuals, but when the dose of EA-2233 was taken up to 1–2 mg, all volunteers were considered to be incapable of performing military duties, with the effects lasting as long as 2–3 days.

DMHP is metabolized in a similar manner to THC, producing the active metabolite 11-hydroxy-DMHP, but the lipophilicity of DMHP is even higher than that of THC itself, giving it a long duration of action and an extended half-life in the body of between 20 and 39 hours, with the half-life of the 11-hydroxy-DMHP metabolite being longer than 48 hours.

DMHP and its esters produce sedation and mild hallucinogenic effects similar to large doses of THC. However, they also cause pronounced hypotension (low blood pressure), occurring at doses well below the hallucinogenic dose, which can lead to severe dizziness, fainting, ataxia and muscle weakness, sufficient to make it difficult to stand upright or carry out any kind of vigorous physical activity.[8]

The acute toxicity of DMHP was found to be low in both human and animal studies, with the therapeutic index measured as a ratio of ED50 to LD50 in animals being around 2000 times. There have been no recorded deaths caused by any DMHP EA-2233 stereoisomers 1–8, only symptoms that are entirely consistent with the highest-known levels of THC intoxication.[8] DMHP has an intravenous LD50 of 63 mg/kg in mice and an intravenous minimal lethal dose of 10 mg/kg in dogs.[11]

Military application

[edit]The combination of strong incapacitating effects and a favorable safety margin led the Edgewood Arsenal team to conclude that DMHP and its derivatives, especially the O-acetyl ester of the most active isomer, EA-2233-2, were among the more promising non-lethal incapacitating agents to come out of their research program.

However, DMHP had the disadvantage of sometimes producing severe hypotension at pre-incapacitating doses, which did not occur with the more widely studied and publicized belladonnoid anticholinergic agents, such as 3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate (BZ), which was discovered and subsequently weaponized.[12] Military applications of synthetic cannabinoids were limited because the drug was both illegal and politically toxic to study via laboratory administration to enlisted servicemen. Both EA-2233-2 and the red-oil THC distillate predecessor, EA-1476, received limited budget and resources compared to the study of other incapacitating agents of BZ derivatives and LSD, (which was widely believed at the time to be a viable mind-control and truth serum useful in a variety of Cold War applications).[8] Initially, the 8 stereoisomers of EA-2233 could not be separated; later, two of the individual isomers of EA-2233 were isolated and tested, but were found to cause both orthostatic hypotension and minimal effects on performance at the very low doses used. EA-2233 did not seem to have sufficient potency to be of military interest, since an oral dose of 60mcg/kg caused a maximum decline of only 40% (at most) in performance at language and number processing tasks.

See also

[edit]- Tinabinol

- Nabitan

- Menabitan

- A-40174

- A-41988

- Δ3-Tetrahydrocannabinol

- Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)

- Tetrahydrocannabiphorol (THCP)

- THCP-O-acetate

- Synthetic cannabinoids

- Effects of cannabis

References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-07-24). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ Adams R, Harfenist M, Loewe S (1949). "New Analogs of Tetrahydrocannabinol. XIX". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 71 (5): 1624–1628. doi:10.1021/ja01173a023.

- ^ Razdan RK (1980). "The Total Synthesis of Cannabinoids". Total Synthesis of Natural Products. Vol. 4. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 185–262. doi:10.1002/9780470129678.ch2. ISBN 978-0-471-05460-3.

- ^ Wilkison DM, Pontzer N, Hosko MJ (July 1982). "Slowing of cortical somatosensory evoked activity by delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and dimethylheptylpyran in alpha-chloralose-anesthetized cats". Neuropharmacology. 21 (7): 705–9. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(82)90014-4. PMID 6289158. S2CID 35663464.

- ^ Winn M, Arendsen D, Dodge P, Dren A, Dunnigan D, Hallas R, Hwang K, Kyncl J, Lee YH, Plotnikoff N, Young P, Zaugg H (April 1976). "Drugs derived from cannabinoids. 5. delta6a,10a-Tetrahydrocannabinol and heterocyclic analogs containing aromatic side chains". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 19 (4): 461–71. doi:10.1021/jm00226a003. PMID 817021.

- ^ Parker LA, Mechoulam R (2003). "Cannabinoid agonists and antagonists modulate lithium-induced conditioned gaping in rats". Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science. 38 (2): 133–45. doi:10.1007/BF02688831. PMID 14527182. S2CID 38974868.

- ^ Huffman JW, Duncan Jr SG, Wiley JL, Martin BR (1997). "Synthesis and pharmacology of the 1′,2′-dimethylheptyl-Δ8-THC isomers: exceptionally potent cannabinoids". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 7 (21): 2799–2804. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(97)10086-5.

- ^ a b c d Ketchum JS (2006). "Chapter 5". Chemical Warfare: Secrets Almost Forgotten. Santa Rosa, CA: ChemBooks Inc. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4243-0080-8.

- ^ Khatchadourian R (12 December 2012). "War of the Mind". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2021-05-08.

- ^ "Possible Long-Term Health Effects of Short-Term Exposure To Chemical Agents". Cholinesterase Reactivators, Psychochemicals and Irritants and Vesicants. Vol. 2. Commission on Life Sciences. The National Academies Press. 1984. pp. 79–99. doi:10.17226/9136. ISBN 978-0-309-07772-9.

- ^ Possible Long-Term Health Effects of Short-Term Exposure to Chemical Agents, Volume 2. 1984. doi:10.17226/9136. ISBN 978-0-309-07772-9.

- ^ Ketchum JS (2006). Chemical Warfare Secrets Almost Forgotten. ChemBooks Inc. ISBN 978-1-4243-0080-8.