Disinformation attacks are strategic deception campaigns[1] involving media manipulation and internet manipulation,[2] to disseminate misleading information,[3] aiming to confuse, paralyze, and polarize an audience.[4] Disinformation can be considered an attack when it occurs as an adversarial narrative campaign that weaponizes multiple rhetorical strategies and forms of knowing—including not only falsehoods but also truths, half-truths, and value-laden judgements—to exploit and amplify identity-driven controversies.[5] Disinformation attacks use media manipulation to target broadcast media like state-sponsored TV channels and radios.[6][7] Due to the increasing use of internet manipulation on social media,[2] they can be considered a cyber threat.[8][9] Digital tools such as bots, algorithms, and AI technology, along with human agents including influencers, spread and amplify disinformation to micro-target populations on online platforms like Instagram, Twitter, Google, Facebook, and YouTube.[10][5]

According to a 2018 report by the European Commission,[11] disinformation attacks can pose threats to democratic governance, by diminishing the legitimacy of the integrity of electoral processes. Disinformation attacks are used by and against governments, corporations, scientists, journalists, activists, and other private individuals.[12][13][14][15] These attacks are commonly employed to reshape attitudes and beliefs, drive a particular agenda, or elicit certain actions from a target audience. Tactics include circulating incorrect or misleading information, creating uncertainty, and undermining the legitimacy of official information sources.[16][17][18]

An emerging area of research focuses on the countermeasures to disinformation attacks.[19][20][18] Technologically, defensive measures include machine learning applications that can flag disinformation on digital platforms.[17] Socially, educational programs are being developed to teach people how to better discern between facts and disinformation online.[21] Journalists publish recommendations for assessing sources.[22] Commercially, revisions to algorithms, advertising, and influencer practices on digital platforms are proposed.[2] Individual interventions include actions that can be taken by individuals to improve their own skills in dealing with information (e.g., media literacy), and individual actions to challenge disinformation.

Goals

[edit]Disinformation attacks involve the intentional spreading of false information, with end goals of misleading, confusing, and encouraging violence,[23] and gaining money, power, or reputation.[24] Disinformation attacks may involve political, economic, and individual actors. They may attempt to influence attitudes and beliefs, drive a specific agenda, get people to act in specific ways, or destroy credibility of individuals or institutions. The presentation of incorrect information may be the most obvious part of a disinformation attack, but it is not the only purpose. The creation of uncertainty and the undermining of both correct information and the credibility of information sources are often intended as well.[16][17][18]

Convincing people to believe incorrect information

[edit]

If individuals can be convinced of something that is factually incorrect, they may make decisions that will run counter to the best interests of themselves and those around them. If the majority of people in a society can be convinced of something that is factually incorrect, the misinformation may lead to political and social decisions that are not in the best interest of that society. This can have serious impacts at both individual and societal levels.[25]

In the 1990s, a British doctor who held a patent on a single-shot measles vaccine promoted distrust of combined MMR vaccine. His fraudulent claims were meant to promote sales of his own vaccine. The subsequent media frenzy increased fear and many parents chose not to immunize their children.[26] This was followed by a significant increase in cases, hospitalizations and deaths that would have been preventable by the MMR vaccine.[27][28] It also led to the expenditure of substantial money on follow-up research that tested the assertions made in the disinformation,[29] and on public information campaigns attempting to correct the disinformation. The fraudulent claim continues to be referenced and to increase vaccine hesitancy.[30]

In the case of the 2020 United States presidential election, disinformation was used in an attempt to convince people to believe something that was not true and change the outcome of the election.[31][32] Repeated disinformation messages about the possibility of election fraud were introduced years before the actual election occurred, as early as 2016.[33][34] Researchers found that much of the fake news originated in domestic right-wing groups. The nonpartisan Election Integrity Partnership reported prior to the election that "What we're seeing right now are essentially seeds being planted, dozens of seeds each day, of false stories... They're all being planted such that they could be cited and reactivated ... after the election."[35] Groundwork was laid through multiple and repeated disinformation attacks for claims that voting was unfair and to delegitimize the results of the election once it occurred.[35] Although the 2020 United States presidential election results were upheld, some people still believe the "big lie".[32]

People who get information from a variety of news sources, not just sources from a particular viewpoint, are more likely to detect disinformation.[36] Tips for detecting disinformation include reading reputable news sources at a local or national level, rather than relying on social media. Beware of sensational headlines that are intended to attract attention and arouse emotion. Fact-check information broadly, not just on one usual platform or among friends. Check the original source of the information. Ask what was really said, who said it, and when. Consider possible agendas or conflicts of interest on the part of the speaker or those passing along the information.[37][38][39][40][41]

Undermining correct information

[edit]Sometimes undermining belief in correct information is a more important goal of disinformation than convincing people to hold a new belief. In the case of combined MMR vaccines, disinformation was originally intended to convince people of a specific fraudulent claim and by doing so promote sales of a competing product.[26] However, the impact of the disinformation became much broader. The fear that one type of vaccine might pose a danger fueled general fears that vaccines might pose a risk. Rather than convincing people to choose one product over another, belief in a whole area of medical research was eroded.[30]

Creation of uncertainty

[edit]There is widespread agreement that disinformation is spreading confusion.[42] This is not just a side effect; confusing and overwhelming people is an intentional objective.[43][44] Whether disinformation attacks are used against political opponents or "commercially inconvenient science", they sow doubt and uncertainty as a way of undermining support for an opposing position and preventing effective action.[45]

A 2016 paper describes social media-driven political disinformation tactics as a "firehose of falsehood" that "entertains, confuses and overwhelms the audience."[46] Four characteristics were illustrated with respect to Russian propaganda. Disinformation is used in a way that is 1) high-volume and multichannel 2) continuous and repetitive 3) ignores objective reality and 4) ignores consistency. It becomes effective by creating confusion and obscuring, disrupting and diminishing the truth. When one falsehood is exposed, "the propagandists will discard it and move on to a new (though not necessarily more plausible) explanation."[46] The purpose is not to convince people of a specific narrative, but to "Deny, deflect, distract".[47]

Countering this is difficult, in part because "It takes less time to make up facts than it does to verify them."[46] There is evidence that false information "cascades" travel farther, faster, and more broadly than truthful information, perhaps due to novelty and emotional loading.[48] Trying to fight a many-headed hydra of disinformation may be less effective than raising awareness of how disinformation works and how to identify it, before an attack occurs.[46] For example, Ukraine was able to warm citizens and journalists about the potential use of state-sponsored deepfakes in advance of an actual attack, which likely slowed its spread.[49]

Another way to counter disinformation is to focus on identifying and countering its real objective.[46] For example, if disinformation is trying to discourage voters, find ways to empower voters and elevate authoritative information about when, where and how to vote.[50] If claims of voter fraud are being put forward, provide clear messaging about how the voting process occurs, and refer people back to reputable sources that can address their concerns.[51]

Undermining of trust

[edit]Disinformation involves more than just a competition between inaccurate and accurate information. Disinformation, rumors and conspiracy theories call into question underlying trust at multiple levels. Undermining of trust can be directed at scientists, governments and media and have very real consequences. Public trust in science is essential to the work of policymakers and to good governance, particularly for issues in medicine, public health, and the environmental sciences. It is essential that individuals, organizations and governments have access to accurate information when making decisions.[13][14]

An example is disinformation around COVID-19 vaccines. Disinformation has targeted the products themselves, the researchers and organizations who develop them, the healthcare professionals and organizations who administer them, and the policy-makers that have supported their development and advised their use.[13][52][53] Countries where citizens had higher levels of trust in society and government appear to have mobilized more effectively against the virus, as measured by slower virus spread and lower mortality rates.[54]

Studies of people's beliefs about the amount of disinformation and misinformation in the news media suggest that distrust of traditional news media tends to be associated with reliance on alternate information sources such as social media. Structural support for press freedoms, a stronger independent press, and evidence of the credibility and honesty of the press can help to restore trust in traditional media as a provider of independent, honest, and transparent information.[55][44]

Undermining of credibility

[edit]A major tactic of disinformation is to attack and attempt to undermine the credibility of people and organizations who are in a position to oppose the disinformation narrative due to their research or position of authority.[56] This can include politicians, government officials, scientists, journalists, activists, human rights defenders and others.[15]

For example, a New Yorker report in 2023 revealed details about the campaign run by the UAE, under which the Emirati President Mohamed bin Zayed paid millions of euros to a Swiss businessman, Mario Brero, for "dark PR" against their targets. Brero and his company Alp Services used the UAE money to create damning Wikipedia entries and publish propaganda articles against Qatar and those with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. Targets included the company Lord Energy, which eventually declared bankruptcy following unproven allegations of links to terrorism.[57] Alp was also paid by the UAE to publish 100 propaganda articles a year against Qatar.[58]

Disinformation attacks on scientists and science, including attacks funded by the tobacco and fossil fuels industries, have been painstakingly documented in books such as Merchants of Doubt,[56][59][60] Doubt Is Their Product,[61][62] and The Triumph of Doubt: Dark Money and the Science of Deception (2020).[63][64] While scientists, doctors and teachers are considered the most trustworthy professionals globally[14] scientists are concerned about whether confidence in science has decreased.[14][53] Sudip Parikh, CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in 2022 is quoted as saying "We now have a significant minority of the population that's hostile to the scientific enterprise... We're going to have to work hard to regain trust."[53] That said, at the same time that disinformation poses a threat, the widespread use of social media by scientists offers an unprecedented opportunity for scientific communication and engagement between scientists and the public, with the potential to increase public knowledge.[14][65]

The American Council on Science and Health has advice for scientists facing a disinformation campaign, and notes that disinformation campaigns often incorporate some elements of truth to make them more convincing. The five recommendations include identifying and acknowledging any parts of the story that are actually true; explaining why other parts are untrue, out of context or manipulated; calling out motivations that may be behind the disinformation, such as financial interests or power; preparing an "accusation audit" in anticipation of further attacks; and maintaining calm and self-control.[66] Others recommend educating oneself about the platforms one uses and the privacy tools that platforms offer to protect personal information and to mute, block, and report online participants. Disinformers and online trolls are unlikely to engage in reasoned discussion or interact in good faith, and responding to them is rarely useful.[67]

Studies clearly document the harassment of scientists, personally and in terms of scientific credibility. In 2021, a Nature survey reported that nearly 60% of scientists who had made public statements about COVID-19 had their credibility attacked. Attacks disproportionately affected those in nondominant identity groups such as women, transgender people, and people of color.[67] A highly visible example is Anthony S. Fauci. He is deeply respected nationally and internationally as an expert on infectious diseases. He also has been subjected to intimidation, harassment and death threats fueled by disinformation attacks and conspiracy theories.[68][69][70] Despite those experiences, Fauci encourages early-career scientists "not to be deterred, because the satisfaction and the degree of contribution you can make to society by getting into public service and public health is immeasurable."[71]

Undermining of collective action including voting

[edit]Individual decisions, like whether or not to smoke, are major targets for disinformation. So are policymaking processes such as the formation of public health policy, the recommendation and adoption of policy measures, and the acceptance or regulation of processes and products. Public opinion and policy interact: public opinion and the popularity of public health measures can strongly influence government policy and the creation and enforcement of industry standards. Disinformation attempts to undermine public opinion and prevent the organization of collection actions, including policy debates, government action, regulation and litigation.[45]

An important type of collective activity is the act of voting. In the 2017 Kenyan general election, 87% of Kenyans surveyed reported encountering disinformation before the August election, and 35% reported being unable to make an informed voting decision as a result.[7] Disinformation campaigns often target specific groups such as black or Latino voters to discourage voting and civic engagement. Fake accounts and bots are used to amplify uncertainty about whether voting really matters, whether voters are "appreciated", and whose interests politicians care about.[72][73] Microtargeting can present messages precisely designed for a chosen population, while geofencing can pinpoint people based on where they go, like churchgoers. In some cases, voter suppression attacks have circulated incorrect information about where and when to vote.[74] During the 2020 U.S. Democratic primaries, disinformation narratives arose around the use of masks and the use of mail-in ballots, relating to whether and how people would vote.[75]

Undermining of functional government

[edit]Disinformation strikes at the foundation of democratic government: "the idea that the truth is knowable and that citizens can discern and use it to govern themselves."[76] Disinformation campaigns are designed by both foreign and domestic actors to gain political and economic advantage. The undermining of functional government weakens the rule of law and can enable both foreign and domestic actors to profit politically and economically. At home and abroad, the goal is to weaken opponents. Elections are an especially critical target, but the day-to-day ability to govern is also undermined.[76][77]

The Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University reports that in 2020, organized social media manipulation campaigns were active in 81 countries, an increase from 70 countries in 2019. 76 of those countries used disinformation attacks. The report describes disinformation as being produced globally "on an industrial scale".[78]

A Russian operation known as the Internet Research Agency (IRA) spent thousands on social media ads to influence the 2016 United States presidential election, confuse the public on key political issues and sow discord. These political ads leveraged user data to micro-target certain populations and spread misleading information, with an end goal of exacerbating polarization and eroding public trust in political institutions.[9][79][19] The Computational Propaganda Project at the Oxford Internet Institute found that the IRA's ads specifically sought to sow mistrust towards the U.S. government among Mexican Americans and discourage voter turnout among African Americans.[80]

An examination of twitter activity prior to the 2017 French presidential election indicates that 73% of the disinformation flagged by Le Monde was traceable to two political communities: one associated with François Fillon (right-wing, with 50.75% of the fake link shares) and another with Marine Le Pen (extreme-right wing, 22.21%). 6% of accounts in the Fillon community and 5% of the Le Pen community were early spreaders of disinformation. Debunking of the disinformation came from other communities, and was most often related to Emmanuel Macron (39.18% of debunks) and Jean-Luc Mélenchon (14% of debunks).[81]

Another analysis, of the 2017 #MacronLeaks disinformation campaign, illustrates frequent patterns of election-related disinformation campaigns. Such campaigns often peak 1–2 days before an election. The scale of a campaign like #MacronLeaks can be comparable to the volume of regular discussion in that time period, suggesting that it can obtain considerable collective attention. About 18 percent of the users involved in #MacronLeaks were identifiable as bots. Spikes in bot content tended to occur slightly ahead of spikes in human-created content, suggesting bots were able to trigger cascades of disinformation. Some bot accounts showed a pattern of previous use: creation shortly before the 2016 U.S. presidential election, brief usage then, and no further activity until early May 2017, prior to the French election. Alt-right media personalities including Britain's Paul Joseph Watson and American Jack Posobiec prominently shared MacronLeaks content prior to the French election.[82] Experts worry that disinformation attacks will increasingly be used to influence national elections and democratic processes.[9]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy (2020) Nancy L. Rosenblum and Russell Muirhead examine the history and psychology of conspiracy theories and the ways in which they are used to de-legitimize the political system. They distinguish between classical conspiracy theory in which actual issues and events (such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy) are examined and combined to create a theory, and a new form of "conspiracism without theory" that relies on repeating false statements and hearsay without factual grounding.[83][84]

Such disinformation exploits human bias towards accepting new information. Humans constantly share information and rely on others to provide information they cannot verify for themselves. Much of that information will be true, whether they ask if it is cold outside or cold in Antarctica. As a result, they tend to believe what they hear. Studies show an "illusory truth effect": the more often people hear a claim, the more likely they are to consider it true. This is the case even when people identify a statement as false the first time they see it; they are likely to rank the probability that it is true higher after multiple exposures.[84][85] Social media is particularly dangerous as a source of disinformation because robots and multiple fake accounts are used to repeat and magnify the impact of false statements. Algorithms track what users click on and recommend content similar to what users have chosen, creating confirmation bias and filter bubbles. In more tightly focused communities an echo chamber effect is enhanced.[86][87][84][88][89][19]

Autocrats have employed domestic voter disinformation attacks to cover up electoral corruption. Voter disinformation can include public statements that assert local electoral processes are legitimate and statements that discredit electoral monitors. Public-relations firms may be hired to execute specialized disinformation campaigns, including media advertisements and behind-the-scenes lobbying, to push the narrative of an honest and democratic election.[90] Independent monitoring of the electoral process is essential to combatting electoral disinformation. Monitoring can include both citizen election monitors and international observers, as long as they are credible. Norms for accurate characterization of elections are based on ethical principles, effective methodologies, and impartial analysis. Democratic norms emphasize the importance of open electoral data, the free exercise of political rights, and protection for human rights.[90]

Increasing polarization and legitimizing violence

[edit]Disinformation attacks can increase political polarization and alter public discourse.[89] Foreign manipulation campaigns may attempt to amplify extreme positions and weaken a target society, while domestic actors may try to demonize political opponents.[76] States with highly polarized political landscapes and low public trust in local media and government are particularly vulnerable to disinformation attacks.[91][92]

There is concern that Russia will employ disinformation, propaganda, and intimidation to destabilize NATO members, such as the Baltic states and coerce them into accepting Russian narratives and agendas.[80][91] During the Russo-Ukrainian War of 2014, Russia combined traditional combat warfare with disinformation attacks in a form of hybrid warfare in its offensive strategy, to sow doubt and confusion among enemy populations and intimidate adversaries, erode public trust in Ukrainian institutions, and boost Russia's reputation and legitimacy.[93] Since escalating the Russo-Ukrainian War with the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia's pattern of disinformation has been described by CBC News as "Deny, deflect, distract".[47]

Thousands of stories have been debunked, including doctored photographs and deepfakes. At least 20 main "themes" are being promoted by Russia propaganda, targeting audiences far beyond Ukraine and Russia. Many of these try to reinforce ideas that Ukraine is somehow Nazi-controlled, that its military forces are weak, and that damage and atrocities are due to Ukrainian, not Russian, actions.[47] Many of the images they examine are shared on Telegraph. Government organizations and independent journalistic groups such as Bellingcat work to confirm or deny such reports, often using open-source data and sophisticated tools to identify where and when information has originated and whether claims are legitimate. Bellingcat works to provide an accurate account of events as they happen and to create a permanent, verified, longer-term record.[94]

Fear-mongering and conspiracy theories are used to encourage polarization, to promote exclusionary narratives, and to legitimize hate speech and aggression.[52][87] As has been painstakingly documented, the period leading up to the Holocaust was marked by repeated disinformation and increasing persecution by the Nazi government,[95][96] culminating in the mass murder[97] of 165,200 German Jews[98] by a "genocidal state".[97] Populations in Africa, Asia, Europe and South America today are considered to be at serious risk for human rights abuses.[7] Changing conditions in the United States have also been identified as increasing risk factors for violence.[92]

Elections are particularly tense political transition points, emotionally charged at any time, and increasingly targeted by disinformation. These conditions increase the risk of individual violence, civil unrest, and mass atrocities. Countries such as Kenya whose history has involved ethnic or election-related violence, foreign or domestic interference, and a high reliance on the use of social media for political discourse, are considered to be at higher risk. The United Nations Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes identifies elections as an atrocity risk indicator: disinformation can act as a threat multiplier for atrocity crime. Recognition of the seriousness of this problem is essential, to mobilize governments, civic society, and social media platforms to take steps to prevent both online and offline harm.[7]

Disinformation channels

[edit]Scientific research

[edit]Disinformation attacks target the credibility of science, particularly in areas of public health[24] and environmental science.[99][14] Examples include denying the dangers of leaded gasoline,[100][101] smoking,[102][103][104] and climate change.[59][105][20][106]

A pattern for disinformation attacks involving scientific sources developed in the 1920s. It illustrates tactics that continue to be used.[107] As early as 1910, industrial toxicologist Alice Hamilton documented the dangers associated with exposure to lead.[108][109] In the 1920s, Charles Kettering, Thomas Midgley Jr. and Robert A. Kehoe of the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation introduced lead into gasoline. Following the sensational madness and deaths of workers at their plants, a Public Health Service conference was held in 1925, to review the use of tetraethyllead (TEL). Hamilton and others warned of leaded gasoline's potential danger to people and the environment. They questioned the research methodology used by Kehoe, who claimed that lead was a "natural" part of the environment and that high lead levels in workers were "normal".[110][111][100] Kettering, Midgley and Kehoe emphasized that a gas additive was needed, and argued that until "it is shown ... that an actual danger to the public is had as a result",[108] the company should be allowed to produce its product. Rather than requiring industry to show that their product was safe before it could be sold, the burden of proof was placed on public health advocates to show uncontestable proof that harm had occurred.[108][112] Critics of TEL were described as "hysterical".[113] With industry support, Kehoe went on to became a prominent industry expert and advocate for the position that leaded gasoline was safe, holding "an almost complete monopoly" on research in the area.[114] It would be decades before his work was finally discredited.[100] In 1988, the EPA estimated that over the previous 60 years, 68 million children suffered high toxic exposure to lead from leaded fuels.[115] A 2022 review reported that the use of lead in gasoline was linked to neurodevelopmental disabilities in children and to neurobehavioral deficits, cardiovascular and kidney disease, and premature deaths in adults.[116]

By the 1950s, the production and use of biased "scientific" research was part of a consistent "disinformation playbook", used by companies in the tobacco,[117] pesticide[118] and fossil fuels industries.[59][105][119] In many cases, the same researchers, research groups, and public relations firms were hired by multiple industries. They repeatedly argued that products were safe while knowing that they were unsafe. When assertions of safety were challenged, it was argued that the products were necessary.[104] Through coordinated and widespread campaigns, they worked to influence public opinion and to manipulate government officials and regulatory agencies, to prevent regulatory or legal action that might interfere with profits.[45]

Similar tactics continue to be used by scientific disinformation campaigns. When proof of harm is presented, it is argued that the proof is not sufficient. The argument that more proof is needed is used to put off action to some future time. Delays are used to block attempts to limit or regulate industry, and to avoid litigation, while continuing to profit. Industry-funded experts carry out research that all too often can be challenged on methodological grounds as well as over conflicts of interest. Disinformers use bad research as a basis for claiming that scientists are not in agreement, and to generate specific claims as part of a disinformation narrative. Opponents are often attacked on a personal level as well as in terms of their scientific work.[120][45][121]

A tobacco industry memo summarized this approach by saying "Doubt is our product".[120] Scientists generally consider a question in terms of the likelihood that a conclusion is supported, given the weight of the best available scientific evidence. Evidence tends to involve measurement, and measurement introduces a potential for error. A scientist may say that available evidence is sufficient to support a conclusion about a problem, but will rarely claim that a problem is fully understood or that a conclusion is 100% certain. Disinformation rhetoric tries to undermine science and sway public opinion by using a "doubt strategy". Reframing the normal scientific process, disinformation often suggests that anything less than 100% certainty implies doubt, and that doubt means there is no consensus about an issue. Disinformation attempts to undermine both certainty about a particular issue and about science itself.[120][45] Decades of disinformation attacks have considerably eroded public belief in science.[45]

Scientific information can become distorted as it is transferred among primary scientific sources, the popular press, and social media. This can occur both intentionally and unintentionally. Some features of current academic publishing like the use of preprint servers make it easier for inaccurate information to become public, particularly if the information reported is novel or sensational.[37]

Steps to protect science from disinformation and interference include both individual actions on the part of scientists, peer reviewers, and editors, and collective actions via research, granting, and professional organizations, and regulatory agencies.[45][122][123]

Traditional media outlets

[edit]Traditional media channels can be used to spread disinformation. For example, Russia Today is a state-funded news channel that is broadcast internationally. It aims to boost Russia's reputation abroad and also depict Western nations, such as the U.S., in a negative light. It has served as a platform to disseminate propaganda and conspiracy theories intended to mislead and misinform its audience.[6]

Within the United States, sharing of disinformation and propaganda has been associated with the development of increasingly "partisan" media, most strongly in right-wing sources such as Breitbart, The Daily Caller, and Fox News.[124] As local news outlets have declined, there has been an increase in partisan media outlets that "masquerade" as local news sources.[125][126] The impact of partisanship and its amplification through the media is documented. For example, attitudes to climate legislation were bipartisan in the 1990s but became intensely polarized by 2010. While media messaging on climate from Democrats increased between 1990 and 2015 and tended to support the scientific consensus on climate change, Republican messaging around climate decreased and became more mixed.[20]

A "gateway belief" that affects people's acceptance of scientific positions and policies is their understanding of the extent of scientific agreement on a topic. Undermining scientific consensus is therefore a frequent disinformation tactic. Indicating that there is a scientific consensus (and explaining the science involved) can help to counter misinformation.[20] Indicating the broad consensus of experts can help to align people's perceptions and understandings with the empirical evidence.[127] Presenting messages in a way that aligns with someone's cultural frame of reference makes them more likely to be accepted.[20]

It is important to avoid false balance, in which opposing claims are presented in a way that is out of proportion to the actual evidence for each side. One way to counter false balance is to present a weight-of-evidence statement that explicitly indicates the balance of evidence for different positions.[127][128]

Social media

[edit]Perpetrators primarily use social media channels as a medium to spread disinformation, using a variety of tools.[129] Researchers have compiled multiple actions through which disinformation attacks occur on social media, which are summarized in the table below.[2][130][131]

| Disinformation attack modes on social media.[2][130][131] | |

|---|---|

| Term | Description |

| Algorithms | Algorithms are leveraged to amplify the spread of disinformation. Algorithms filter and tailor information for users and modify the content they consume.[132] A study found that algorithms can be radicalization pipelines because they present content based on its user engagement levels. Users are drawn more to radical, shocking, and click-bait content.[133] As a result, extremist, attention-grabbing posts can garner high levels of engagement through algorithms. Disinformation campaigns may leverage algorithms to amplify their extremist content and sow radicalization online.[134] |

| Astroturfing | A centrally coordinated campaign that mimics grassroots activism by making participants pretend to be ordinary citizens. Astroturfing is putting out overwhelming amounts of content promoting similar messages from multiple fake accounts. This gives an impression of widespread consensus around a message, simulating a grassroots response while hiding its origin. Flooding is the spamming of social media with messages to shape a narrative or drown out opposition. Repeated exposure to a message is more likely to establish it in someone's mind. Disinformation actors will often tailor messages to a particular audience, to engage with individuals and build credibility with them, before exposing them to more extreme or misleading views.[135][136][137] |

| Bots | Bots are automated agents that can produce and spread content on online social platforms. Many bots can engage in basic interactions with other bots and humans. In disinformation attack campaigns, they are leveraged to rapidly disseminate disinformation and breach digital social networks. Bots can produce the illusion that one piece of information is coming from a variety of different sources. In doing so, disinformation attack campaigns make their content seem believable through repeated and varied exposure.[138] By flooding social media channels with repeated content, bots can also alter algorithms and shift online attention to disinformation content.[17] |

| Clickbait | The deliberate use of misleading headlines and thumbnails to increase online traffic for profit or popularity |

| Conspiracy theories | Rebuttals of official accounts that propose alternative explanations in which individuals or groups act in secret |

| Culture wars | A phenomenon in which multiple groups of people, who hold entrenched values, attempt to steer public policy contentiously |

| Deep fakes | A deep fake is digital content (audio and video) that has been manipulated. Deep fake technology can be harnessed to defame, blackmail, and impersonate. Due to its low costs and efficiency, deep fakes can be used to spread disinformation more quickly and in greater volume than humans can. Disinformation attack campaigns may leverage deep fake technology to generate disinformation concerning people, states, or narratives. Deep fake technology can be weaponized to mislead an audience and spread falsehoods.[139] |

| Echo chambers | An epistemic environment in which participants encounter beliefs and opinions that coincide with their own |

| Hoax | News in which false facts are presented as legitimate |

| Fake news | The deliberate creation of pseudo-journalism and the instrumentalization of the term to delegitimize news media |

| Personas | Personas and websites may be created with the intention of presenting and spreading incorrect information in a way that makes it appear credible. A faked website may present itself as being from a professional or educational organization. A person may imply that they have credentials or expertise. Disinformation actors may create whole networks of interconnected supposed "authorities".[135] Whether we assume that someone is truthful and whether we choose to fact-check what we see are predictors of susceptibility to disinformation.[16] Carefully consider sources and claims of authority; cross-check information against a wide range of sources. |

| Propaganda | Organized mass communication, on a hidden agenda, and with a mission to conform belief and action by circumventing individual reasoning |

| Pseudoscience | Accounts that claim the explanatory power of science, borrow its language and legitimacy but diverge substantially from its quality criteria |

| Rumors | Unsubstantiated news stories that circulate while not corroborated or validated |

| Trolling | Networked groups of digital influencers that operate ‘click armies' designed to mobilize public sentiment |

An app called "Dawn of Glad Tidings," developed by Islamic State members, assists in the organization's efforts to rapidly disseminate disinformation in social media channels. When a user downloads the app, they are prompted to link it to their Twitter account and grant the app access to tweeting from their personal account. This app allows for automated Tweets to be sent out from real user accounts and helps create trends across Twitter that amplify disinformation produced by the Islamic State on an international scope.[80]

In many cases, individuals and companies in different countries are paid to create false content and push disinformation, sometimes earning both payments and advertising revenue by doing so.[129][2] "Disinfo-for-hire actors" often promote multiple issues, or even multiple sides in the same issue, solely for material gain.[140] Others are motivated politically or psychologically.[141][2]

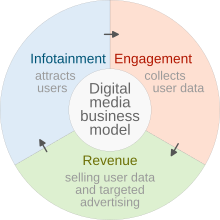

More broadly, the monetization practices of social media and online advertising can be exploited to amplify disinformation.[142] Social media's business model can be used to spread disinformation Media outlets (1) provide content to the public at little or no cost, (2) capture and refocus public attention and (3) collect, use and resell user data. Advertising companies, publishers, influencers, brands, and clients may benefit from disinformation in a variety of ways.[2]

In 2022, the Journal of Communication published a study of the political economy underlying disinformation around vaccines. Researchers identified 59 English-language "actors" that provided "almost exclusively anti-vaccination publications". Their websites monetized disinformation through appeals for donations, sales of content-based media and other merchandise, third-party advertising, and membership fees. Some maintained a group of linked websites, attracting visitors with one site and appealing for money and selling merchandise on others. In how they gained attention and obtained funding, their activities displayed a "hybrid monetization strategy". They attracted attention by combining eye-catching aspects of "junk news" and online celebrity promotion. At the same time, they developed campaign-specific communities to publicize and legitimize their position, similar to radical social movements.[141]

Social engineering

[edit]Emotion is used and manipulated to spread disinformation and false beliefs.[19] Arousing emotions can be persuasive. When people feel strongly about something, they are more likely to see it as true.[85] Emotion can also cause people to think less clearly about what they are reading and the credibility of its source. Content that appeals to emotion is more likely to spread quickly on the internet. Fear, confusion, and distraction can all interfere with people's ability to think critically and make good decisions.[143]

Human psychology is leveraged to make disinformation attacks more potent and viral.[19] Psychological phenomena, such as stereotyping, confirmation bias, selective attention, and echo chambers, contribute to the virality and success of disinformation on digital platforms.[138][144][5] Disinformation attacks are often considered a type of psychological warfare because of their use of psychological techniques to manipulate populations.[145][25]

Perceptions of identify and a sense of belonging are manipulated so as to influence people.[19] Feelings of social belonging are reinforced to encourage affiliation with a group and discourage dissent. This can make people more susceptible to an influencer or leader who may encourage his "engaged followership" to attack others. The type of behavior has been compared to the collective behavior of mobs and is similar to dynamics within cults.[67][146][147]

Defense measures

[edit]As has been noted by the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, "The misinformation problem is social and not just technological or legal."[148] It raises serious ethical issues about how we engage with each other.[149] The 2023 Summit on "Truth, Trust, and Hope", held by the Nobel Committee and the US National Academy of Science, identified disinformation as more dangerous than any other crisis, because of the way in which it hampers the addressing and resolution of all other problems.[150]

Defensive measures against disinformation can occur at a wide variety of levels, in diverse societies, under different laws and conditions. Responses to disinformation can involve institutions, individuals, and technologies, including government regulation, self-regulation, monitoring by third parties, the actions of private actors, the influence of crowds, and technological changes to platform architecture and algorithmic behaviors.[151][152] It is important to develop and share best practices for countering disinformation and building resilience against it.[76]

Existing social, legal and regulatory guidelines may not apply easily to actions in an international virtual world, where private corporations compete for profitability, often on the basis of user engagement.[151][2] Ethical concerns apply to some of the possible responses to disinformation, as people debate issues of content moderation, free speech, the right to personal privacy, human identity, human dignity, suppression of human rights and religious freedom, and the use of data.[149] The scope of the problem means that "Building resilience to and countering manipulative information campaigns is a whole-of-society endeavor."[76]

National and international laws

[edit]While authoritarian regimes have chosen to use disinformation attacks as a policy tool, their use poses specific dangers for democratic governments: using equivalent tactics will further deepen public distrust of political processes and undermine the basis of democratic and legitimate government. "Democracies should not seek to covertly influence public debate either by deliberately spreading information that is false or misleading or by engaging in deceptive practices, such as the use of fictitious online personas."[153] Further, democracies are encouraged to play to their strengths, including rule of law, respect for human rights, cooperation with partners and allies, soft power, and technical capability to address cyber threats.[153]

The constitutional norms that govern a society are needed both to make governance effective and to avert tyranny.[148] Providing accurate information and countering disinformation are legitimate activities of government. The OECD suggests that public communication of policy responses should follow open government principles of integrity, transparency, accountability and citizen participation.[154] A discussion of the US government's ability to legally respond to disinformation argues that responses should be based on principles of transparency and generality. Responses should avoid ad hominem attacks, racial appeals, or selectivity in the person responded to. Criticism should focus first on providing correct information and secondarily on explaining why the false information is wrong, rather than focusing on the speaker or repeating the false narrative.[148][143][155]

In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple factors created "space for misinformation to proliferate". Government responses to this public health issue indicate several areas of weakness including gaps in basic public health knowledge, lack of coordination in government communication, and confusion about how to address a situation involving significant uncertainty. Lessons from the pandemic include the need to admit uncertainty when it exists, and to distinguish clearly between what is known and what is not yet known. Science is a process, and it is important to recognize and communicate that scientific understanding and related advice will change over time on the basis of new evidence.[154]

Regulation of disinformation raises ethical issues. The right to freedom of expression is recognized as a human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law by the United Nations. Many countries have constitutional law that protects free speech. A country's laws may identify specific categories of speech that are or are not protected, and specific parties whose actions are restricted.[151]

United States

[edit]The First Amendment to the United States Constitution protects both freedom of speech and freedom of the press from interference by the United States Congress. As a result, the regulation of disinformation in the United States tends to be left to private rather than government action.[151]

The First Amendment does not protect speech used to incite violence or break the law,[156] or "obscenity, child pornography, defamatory speech, false advertising, true threats, and fighting words".[157] With these exceptions, debating matters of "public or general interest" in a way that is "uninhibited, robust and wide-open" is expected to benefit a democratic society.[158]

The First Amendment tends to rely on counterspeech as a workable corrective measure, preferring refutation of falsehood to regulation.[151][148] There is an underlying assumption that identifiable parties will have the opportunity to share their views on a relatively level playing field, where a public figure being drawn into a debate will have increased access to the media and a chance of rebuttal.[158] This may no longer hold true when rapid, massive disinformation attacks are deployed against an individual or group through anonymous or multiple third parties, where "A half-day's delay is a lifetime for an online lie."[148]

Other civil and criminal laws are intended to protect individuals and organizations in cases where speech involves defamation of character (libel or slander) or fraud. In such cases, being incorrect is not sufficient to justify legal or governmental action. Incorrect information must demonstrably cause harm to others or enable the liar to gain an unjustified benefit. Someone who has knowingly spread disinformation and used that disinformation to gain money may be chargeable with fraud.[159] The extent to which these existing laws can be effectively applied against disinformation attacks is unclear.[151][148][160] Under this approach, a subset of disinformation, which is not only untrue but "communicated for the purpose of gaining profit or advantage by deceit and causes harm as a result" could be considered "fraud on the public",[31] and no longer considered a type of protected speech. Much of the speech that constitutes disinformation would not meet this test.[31]

European Union

[edit]The Digital Services Act (DSA) is a Regulation in EU law that establishes a legal framework within the European Union for the management of content on intermediaries, including illegal content, transparent advertising, and disinformation.[161][162] The European Parliament approved the DSA along with the Digital Markets Act on 5 July 2022.[163] The European Council gave its final approval to the Regulation on a Digital Services Act on 4 October 2022.[164] It was published in the Official Journal of the European Union on the 19 October 2022. Affected service providers will have until 1 January 2024 to comply with its provisions.[163] DSA aims to harmonise differing laws at the national level in the European Union[161] including Germany (NetzDG), Austria ("Kommunikationsplattformen-Gesetz") and France ("Loi Avia").[165] Platforms with more than 45 million users in the European Union, including Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and TikTok would be subject to the new obligations. Companies failing to meet those obligations could risk fines of up to 10% of their annual turnover.[166]

As of April 25, 2023, Wikipedia was one of 17 platforms to be designated a Very Large Online Platform (VLOP) by the EU Commission, with regulations taking effect as of August 25, 2023.[167] In addition to any steps taken by the Wikimedia Foundation, Wikipedia's compliance with the Digital Services Act will be independently audited, on a yearly basis, beginning in 2024.[168]

Russia and China

[edit]It has been suggested that China and Russia are jointly portraying the United States and the European Union in an adversarial way in terms of the use of information and technology. This narrative is then used by China and Russia to justify the restriction of freedom of expression, access to independent media, and internet freedoms. They have jointly called for the "internationalization of internet governance", meaning distribution of control of the internet to individual sovereign states. In contrast, calls for global internet governance emphasize the existence of a free and open internet, whose governance involves citizens and civil society.[169][76] Democratic governments need to be aware of the potential impact of measures used to restrict disinformation both at home and abroad. This is not an argument that should block legislation, but it should be taken into consideration when forming legislation.[76]

Private regulation

[edit]In the United States, the First Amendment limits the actions of Congress, not those of private individuals, companies and employers.[156] Private entities can establish their own rules (subject to local and international laws) for dealing with information.[157] Social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Telegram could legally establish guidelines for moderation of information and disinformation on their platforms. Ideally, platforms should attempt to balance free expression by their users against the moderation or removal of harmful and illegal speech.[38][170]

Sharing of information through broadcast media and newspapers has been largely self-regulating. It has relied on voluntary self-governance and standard-setting by professional organizations such as the US Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ). The SPJ has a code of ethics for professional accountability, which includes seeking and reporting truth, minimizing harm, accountability and transparency.[171] The code states that "whoever enjoys a special measure of freedom, like a professional journalist, has an obligation to society to use their freedoms and powers responsibly."[172] Anyone can write a letter to the editor of the New York Times, but the Times will not publish that letter unless they choose to do so.[173]

Arguably, social media platforms are treated more like the post office—which passes along information without reviewing it—than they are like journalists and print publishers who make editorial decisions and are expected to take responsibility for what they publish. The kinds of ethical, social and legal frameworks that journalism and print publishing have developed have not been applied to social media platforms.[174]

It has been pointed out that social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter lack incentives to control disinformation or to self-regulate.[171][151][175] To the extent that platforms rely on advertising for revenue, it is to their financial benefit to maximize user engagement, and the attention of users is demonstrably captured by sensational content.[19][176] Algorithms that push content based on user search histories, frequent clicks and paid advertising leads to unbalanced, poorly sourced, and actively misleading information. It is also highly profitable.[171][175][177] When countering disinformation, the use of algorithms for monitoring content is cheaper than employing people to review and fact-check content. People are more effective at detecting disinformation. People may also bring their own biases (or their employer's biases) to the task of moderation.[174]

Privately owned social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter can legally develop regulations, procedures and tools to identify and combat disinformation on their platforms.[178] For example, Twitter can use machine learning applications to flag content that does not comply with its terms of service and identify extremist posts encouraging terrorism. Facebook and Google have developed a content hierarchy system where fact-checkers can identify and de-rank possible disinformation and adjust algorithms accordingly.[9] Companies are considering using procedural legal systems to regulate content on their platforms as well. Specifically, they are considering using appellate systems: posts may be taken down for violating terms of service and posing as a disinformation threat, but users can contest this action through a hierarchy of appellate bodies.[134]

Blockchain technology has been suggested as a potential defense mechanism against internet manipulation.[179] While blockchain was originally developed to create a ledger of transactions for the digital currency bitcoin, it is now widely used in applications where a permanent record or history of assets, transactions, and activities is desired. It provides a potential for transparency and accountability,[180] Blockchain technology could be applied to make data transport more secure in online spaces and the Internet of Things networks, making it difficult for actors to alter or censor content and carry out disinformation attacks.[181] Applying techniques such as blockchain and keyed watermarking on social media/messaging platforms could also help to detect and curb disinformation attacks. The density and rate of forwarding of a message could be observed to detect patterns of activity that suggest the use of bots and fake account activity in disinformation attacks. Blockchain could support both backtracking and forward tracking of events that involve the spreading of disinformation. If the content is deemed dangerous or inappropriate, its spread could be curbed immediately.[179]

Understandably, methods for countering disinformation that involve algorithmic governance raise ethical concerns. The use of technologies that track and manipulate information raises questions about "who is accountable for their operation, whether they can create injustices and erode civic norms, and how we should resolve their (un)intended consequences".[171][182][183]

A study from the Pew Research Center reports that public support for restriction of disinformation by both technology companies and government increased among Americans from 2018 to 2021. However, views on whether government and technology companies should take such steps became increasingly partisan and polarized during the same time period.[184]

Collaborative measures

[edit]Cyber security experts claim that collaboration between public and private sectors is necessary to successfully combat disinformation attacks.[19] Recommended cooperative defense strategies include:

- The creation of "disinformation detection consortiums" where stakeholders (i.e. private social media companies and governments) convene to discuss disinformation attacks and come up with mutual defense strategies.[17]

- Sharing critical information between private social media companies and the government, so that more effective defense strategies can be developed.[185][17]

- Coordination among governments to create a unified and effective response against transnational disinformation campaigns.[17]

However, in the United States, the Republican party is actively opposing both disinformation research and government involvement in fighting disinformation. Republicans gained a majority in the House in January 2023. Since then, the House Judiciary Committee has used legal action to send letters, subpoenas, and threats of legal action to researchers, demanding notes, emails and other records from researchers and even student interns, dating back to 2015. Institutions affected include the Stanford Internet Observatory at Stanford University, the University of Washington, the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab and the social media analytics firm Graphika. Projects include the Election Integrity Partnership, formed to identify attempts "to suppress voting, reduce participation, confuse voters or delegitimize election results without evidence"[186] and the Virality Project, which has examined the spread of false claims about vaccines. Researchers argue that they have academic freedom to study social media and disinformation as well as freedom of speech to report their results.[186][187][188] Despite conservative claims that the government acted to censor speech online, "no evidence has emerged that government officials coerced the companies to take action against accounts".[186]

At the state level, state governments that were politically aligned with anti-vaccine activists successfully sought a preliminary injunction to prevent the Biden Administration from urging social media companies to fight misinformation about public health. The order issued by United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in 2023 "severely limits the ability of the White House, the surgeon general, [and] the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention... to communicate with social media companies about content related to COVID-19... that the government views as misinformation".[189]

Strengthening civil society

[edit]Reports on disinformation in Armenia[52] and Asia[76] identify key issues and make recommendations. These can be applied to many other countries, particularly those experiencing "both profound disruption and an opportunity for change".[52] The report emphasizes the importance of strengthening civil society by protecting the integrity of elections and rebuilding trust in public institutions. Steps to support the integrity of elections include: ensuring a free and fair process, allowing independent observation and monitoring, allowing independent journalistic access, and investigating electoral infractions. Other suggestions include rethinking state communication strategies to enable all levels of government to more effectively communicate and to address disinformation attacks.[52]

National dialogue bringing together diverse public, community, political, state and nonstate actors as stakeholders is recommended for effective long-term strategic planning. Creating a unified strategy for legislation to deal with information spaces is recommended. Balancing concerns about freedom of expression with protections for individuals and democratic institutions is critical.[52][190][191]

Another concern is the development of a healthy information environment that supports fact-based journalism, truthful discourse, and independent reporting at the same time that it rejects information manipulation and disinformation. Key issues for the support of resilient independent media include transparency of ownership, financial viability, editorial independence, media ethics and professional standards, and mechanisms for self-regulation.[52][190][191][192][76]

During the 2018 Mexican general election, the collaborative journalism project Verificado 2018 was established to address misinformation. It involved at least eighty organizations, including local and national media outlets, universities and civil society and advocacy groups. The group researched online claims and political statements and published joint verifications. During the course of the election, they produced over 400 notes and 50 videos documenting false claims and suspect sites, and tracked instances where fake news went viral.[193] Verificado.mx received 5.4 million visits during the election, with its partner organizations registering millions more.[194]: 25 To deal with the sharing of encrypted messages via WhatsApp, Verificado set up a hotline where WhatsApp users could submit messages for verification and debunking. Over 10,000 users subscribed to Verificado's hotline.[193]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Organizations promoting civil society and democracy, independent journalists, human rights defenders, and other activists are increasingly targets of disinformation campaigns and violence. Their protection is essential. Journalists, activists and organizations can be key allies in combating false narratives, promoting inclusion, and encouraging civic engagement. Oversight and ethics bodies are also critical.[52][195] Organizations that have developed resources and trainings to better support journalists against online and offline violence and violence against women include the Coalition Against Online Violence,[196][197] Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas,[198] International Women's Media Foundation,[199] UNESCO,[195][198] PEN America.[200] and others.[201]

Education and awareness

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Media literacy education and information on how to identify and combat disinformation is recommended for public schools and universities.[52] In 2022, countries in the European Union were ranked on a Media Literacy Index to measure resilience against disinformation. Finland, the highest ranking country, has developed an extensive curriculum that teaches critical thinking and resistance to information warfare, and integrated it into its public education system. Fins also rank high in trust in government authorities and the media.[202][203] Following a 2007 cyberattack that included disinformation tactics, the country of Estonia focused on improving its cyberdefenses and made media literacy education a major focus from kindergarten through to high school.[204][205]

In 2018, the Executive Vice President of the European Commission for A Europe Fit for the Digital Age gathered a group of experts to produce a report with recommendations for teaching digital literacy. Proposed digital literacy curricula familiarize students with fact-checking websites such as Snopes and FactCheck.org. This curricula aims to equip students with critical thinking skills to discern between factual content and disinformation online.[21] Suggested areas to focus on include skills in critical thinking,[206] information literacy,[207][208] science literacy[209] and health literacy.[24]

Another approach is to build interactive games such as the Cranky Uncle game, which teaches critical thinking and inoculates players against techniques of disinformation and science denial. The Cranky Uncle game is freely available and has been translated into at least 9 languages.[210][211] Videos for teaching critical thinking and addressing disinformation can also be found online.[212][213]

Training and best practices for identifying and countering disinformation are being developed and shared by groups of journalists, scientists, and others (e.g. Climate Action Against Disinformation,[22] PEN America,[214][215][216] UNESCO,[44] Union of Concerned Scientists,[217][218] Young African Leaders Initiative[219]).

Research suggests that a number of tactics have proven useful against scientific disinformation around climate change. These include: 1) providing clear explanations about why climate change is occurring 2) indicating that there is scientific consensus about the existence of climate change and about its basis in human actions 3) presenting information in ways that are culturally aligned with the listener 4) "inoculating" people by clearly identifying misinformation (ideally before a myth is encountered, but also later through debunking).[20][18]

A "Toolbox of Interventions Against Online Misinformation and Manipulation" reviews research into individually-focused interventions to combat misinformation and their possible effectiveness. Tactics include:[220][221]

- Accuracy prompts – Social media and other sources of information can cue people to think about accuracy before sharing information online[222][223]

- Debunking – To expose false information, first focus on highlighting the true facts, before pointing out that misleading information is going to be given, and only then specifying the misinformation and explaining why it is wrong. Finally, the correct explanation should be reinforced.[143][155] This way of countering disinformation is sometimes referred to as a "truth sandwich".[224]

- Avoid confrontation. Evidence suggests that when someone feels challenged or threatened by information that does not fit their existing worldview, they will "double down" on their previous beliefs rather than considering the new information. However, if clear evidence can be presented in a friendly and non-confrontational way, without arousing aggression or hostility, the new information is more likely to be considered.[19]

- Friction – Clickbait aimed at spreading disinformation tries to get people to react quickly and emotionally. Cueing people to slow down and think about their actions (e.g. by displaying a prompt like "Want to read this before sharing?") can limit the spread of disinformation.[225]

- Inoculation – Preemptively warning people about possible disinformation and techniques sued to spread disinformation, before they are exposed to an intended false message, can help them to identify false messages and attempts at manipulation.[226][227] Short videos that describe specific tactics like fearmongering, the use of emotional language, or fake experts, help people resist online persuasion techniques.[228]

- Lateral reading – Fact check information by looking for independent and reputable sources. Verify the credibility of information on a website by independently searching the Web, not just looking at the original site.[229][230]

- Media-literacy tips – Specific strategies for spotting false news, such as those used in Facebook's 2017 "Tips to Spot False News" (e.g. "be sceptical of headlines", "look closely at the URL") can help users to better discriminate between real and fake news stories.[231][204]

- Rebuttals of science denialism – Scientific denial can involve both inaccurate assertions about a particular topic (topic rebuttal) and rhetorical techniques and strategies that undermine, mislead or deny the validity of science as an activity (technique rebuttal). Countering science denial must address both types of tactics.[232][233][20][234] Research into science denial raises questions about the societal understanding of science and scientific processes and how to improve science education.[235][236][237][238]

- Self-reflection tools – Various cognitive, social and affective factors are involved in beliefs, judgments and decisions.[143] Individual differences in personality traits such as extraversion and the tendency to feel anger, anxiety, stress or depression, and fear are associated with a higher likelihood of sharing rumors online.[239] Higher levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness and open-mindedness, and lower levels of extraversion are related to greater accuracy when identifying headlines as true or false. People who are more accurate in identifying headlines also report spending less time reading the news each week.[240] Self-reflection tools that help people to be aware of their possible vulnerability may help them to identify microtargeting directed at individual traits.[241]

- Social norms - Disinformation often works to undermine social norms, normalizing and thriving on an atmosphere of confusion, distrust, fear and violence.[242][243][19] In contrast, changing or emphasizing positive social norms is often a focus in programs attempting to improve health and social behaviors.[244] Social norms may help to reinforce the importance of accurate information, and discourage the sharing and using of false information.[245][246] Strong social norms can influence members' priorities, expectations, and bonds with one another.[247] They may encourage the adoption of best practices and higher standards for dealing with disinformation, on the part of the news industry, technology companies, educational institutions, and individuals.[245][246][248]

- Warning and fact-checking labels - Online platforms have made intermittent attempts to flag information whose content or source is considered questionable. Warning labels can indicate that a piece of information or a source may be misleading.[243] Fact-checking labels can give the ratings of professional or independent fact-checkers using a rating scale (e.g., as false or altered) or indicating grounds for their rating.[249]

See also

[edit]- Deepfake

- Doomscrolling

- Fake news

- Internet Research Agency

- Media manipulation

- Misinformation

- Propaganda

- Psychological warfare

- Russian web brigades

References

[edit]- ^ Bennett, W Lance; Livingston, Steven (April 2018). "The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions". European Journal of Communication. 33 (2): 122–139. doi:10.1177/0267323118760317. ISSN 0267-3231. S2CID 149557690.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Diaz Ruiz, Carlos (30 October 2023). "Disinformation on digital media platforms: A market-shaping approach". New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/14614448231207644. ISSN 1461-4448. S2CID 264816011.

- ^ Wardle, Claire (1 April 2023). "Misunderstanding Misinformation". Issues in Science and Technology. 29 (3): 38–40. doi:10.58875/ZAUD1691. S2CID 257999777.

- ^ Fallis, Don (2015). "What Is Disinformation?". Library Trends. 63 (3): 401–426. doi:10.1353/lib.2015.0014. hdl:2142/89818. ISSN 1559-0682. S2CID 13178809.

- ^ a b c d Diaz Ruiz, Carlos; Nilsson, Tomas (2023). "Disinformation and Echo Chambers: How Disinformation Circulates on Social Media Through Identity-Driven Controversies". Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 42 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1177/07439156221103852. S2CID 248934562.

- ^ a b Ajir, Media; Vailliant, Bethany (2018). "Russian Information Warfare: Implications for Deterrence Theory". Strategic Studies Quarterly. 12 (3): 70–89. ISSN 1936-1815. JSTOR 26481910.

- ^ a b c d McKay, Gillian (22 June 2022). "Disinformation and Democratic Transition: A Kenyan Case Study". Stimson Center.

- ^ Caramancion, Kevin Matthe (March 2020). "An Exploration of Disinformation as a Cybersecurity Threat". 2020 3rd International Conference on Information and Computer Technologies (ICICT). pp. 440–444. doi:10.1109/ICICT50521.2020.00076. ISBN 978-1-7281-7283-5. S2CID 218651389.

- ^ a b c d Downes, Cathy (2018). "Strategic Blind–Spots on Cyber Threats, Vectors and Campaigns". The Cyber Defense Review. 3 (1): 79–104. ISSN 2474-2120. JSTOR 26427378.

- ^ Katyal, Sonia K. (2019). "Artificial Intelligence, Advertising, and Disinformation". Advertising & Society Quarterly. 20 (4). doi:10.1353/asr.2019.0026. ISSN 2475-1790. S2CID 213397212.

- ^ "Communication - Tackling online disinformation: a European approach". European Commission. 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ "Disinformation attacks have arrived in the corporate sector. Are you ready?". PwC. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Pertwee, Ed; Simas, Clarissa; Larson, Heidi J. (March 2022). "An epidemic of uncertainty: rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy". Nature Medicine. 28 (3): 456–459. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01728-z. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 35273403. S2CID 247385552.

- ^ a b c d e f Gundersen, Torbjørn; Alinejad, Donya; Branch, T.Y.; Duffy, Bobby; Hewlett, Kirstie; Holst, Cathrine; Owens, Susan; Panizza, Folco; Tellmann, Silje Maria; van Dijck, José; Baghramian, Maria (17 October 2022). "A New Dark Age? Truth, Trust, and Environmental Science". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47 (1): 5–29. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-120920-015909. hdl:10852/99734. S2CID 250659393.

- ^ a b Nyst, Carly; Monaco, Nick (2018). STATE-SPONSORED TROLLING How Governments Are Deploying Disinformation as Part of Broader Digital Harassment Campaigns (PDF). Palo Alto, CA: Institute for the Future. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Collado, Zaldy C.; Basco, Angelica Joyce M.; Sison, Albin A. (2020-06-26). "Falling victims to online disinformation among young Filipino people: Is human mind to blame?". Cognition, Brain, Behavior. 24 (2): 75–91. doi:10.24193/cbb.2020.24.05. S2CID 225786653.

- ^ a b c d e f g Frederick, Kara (2019). The New War of Ideas: Counterterrorism Lessons for the Digital Disinformation Fight. Center for a New American Security.

- ^ a b c d Hornsey, Matthew J.; Lewandowsky, Stephan (November 2022). "A toolkit for understanding and addressing climate scepticism". Nature Human Behaviour. 6 (11): 1454–1464. doi:10.1038/s41562-022-01463-y. hdl:1983/c3db005a-d941-42f1-a8e9-59296c66ec9b. ISSN 2397-3374. PMC 7615336. PMID 36385174. S2CID 253577142.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nemr, Christina; Gangware, William (March 28, 2019). Weapons of Mass Distraction: Foreign State-Sponsored Disinformation in the Digital Age (PDF). Park Advisors. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lewandowsky, Stephan (1 April 2021). "Climate Change Disinformation and How to Combat It". Annual Review of Public Health. 42 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102409. hdl:1983/c6a6a1f8-6ba4-4a12-9829-67c14c8ae2e5. ISSN 0163-7525. PMID 33355475. S2CID 229691604. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ a b Glisson, Lane (2019). "Breaking the Spin Cycle: Teaching Complexity in the Age of Fake News". Portal: Libraries and the Academy. 19 (3): 461–484. doi:10.1353/pla.2019.0027. ISSN 1530-7131. S2CID 199016070.

- ^ a b Gibson, Connor (2022). Journalist Field Guide: Navigating Climate Misinformation (PDF). Climate Action Against Disinformation.

- ^ Brancati, Dawn; Penn, Elizabeth M (2023). "Stealing an Election: Violence or Fraud?". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 67 (5): 858–892. doi:10.1177/00220027221120595. ISSN 0022-0027.

- ^ a b c Swire-Thompson, Briony; Lazer, David (2 April 2020). "Public Health and Online Misinformation: Challenges and Recommendations". Annual Review of Public Health. 41 (1): 433–451. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094127. ISSN 0163-7525. PMID 31874069. S2CID 209473873.

- ^ a b Lewandowsky, Stephan; Ecker, Ullrich K. H.; Seifert, Colleen M.; Schwarz, Norbert; Cook, John (December 2012). "Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 13 (3): 106–131. doi:10.1177/1529100612451018. ISSN 1529-1006. PMID 26173286. S2CID 42633.

- ^ a b Davidson, M (December 2017). "Vaccination as a cause of autism-myths and controversies". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 19 (4): 403–407. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.4/mdavidson. PMC 5789217. PMID 29398935.

- ^ Quick, Jonathan D.; Larson, Heidi (February 28, 2018). "The Vaccine-Autism Myth Started 20 Years Ago. It Still Endures Today". Time. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Dubé, Ève; Ward, Jeremy K.; Verger, Pierre; MacDonald, Noni E. (1 April 2021). "Vaccine Hesitancy, Acceptance, and Anti-Vaccination: Trends and Future Prospects for Public Health". Annual Review of Public Health. 42 (1): 175–191. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102240. ISSN 0163-7525. PMID 33798403. S2CID 232774243.

- ^ Gerber, JS; Offit, PA (15 February 2009). "Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (4): 456–61. doi:10.1086/596476. PMC 2908388. PMID 19128068.

- ^ a b Pluviano, S; Watt, C; Della Sala, S (2017). "Misinformation lingers in memory: Failure of three pro-vaccination strategies". PLOS ONE. 12 (7): e0181640. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1281640P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181640. PMC 5547702. PMID 28749996.

- ^ a b c Henricksen, Wes (13 June 2023). "Disinformation and the First Amendment: Fraud on the Public". St. John's Law Review. 96 (3): 543–589.

- ^ a b "Exhaustive fact check finds little evidence of voter fraud, but 2020's 'Big Lie' lives on". PBS NewsHour. 17 December 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Kuznia, Rob; Devine, Curt; Black, Nelli; Griffin, Drew (14 November 2020). "Stop the Steal's massive disinformation campaign connected to Roger Stone | CNN Business". CNN. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Foreign Threats to the 2020 US Federal Elections" (PDF). Intelligence Committee Assessment. 10 March 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ a b Miller, Greg (26 Oct 2020). "As U.S. election nears, researchers are following the trail of fake news". Science. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Atske, Sara (22 February 2021). "3. Misinformation and competing views of reality abounded throughout 2020". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Retrieved 19 January 2023.