Dred Scott | |

|---|---|

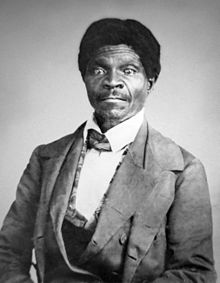

Scott c. 1857 | |

| Born | c. 1799 |

| Died | September 17, 1858 (aged approximately 59) St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Resting place | Calvary Cemetery |

| Known for | Dred Scott v. Sandford |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4[a] |

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Dred Scott (c. 1799 – September 17, 1858) was an enslaved African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for the freedom of themselves and their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case of 1857, popularly known as the "Dred Scott decision". The Scotts claimed that they should be granted freedom because Dred had lived in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory for four years, where slavery was illegal, and laws in those jurisdictions said that slave holders gave up their rights to slaves if they stayed for an extended period.

In a landmark case, the United States Supreme Court decided 7–2 against Scott, finding that neither he nor any other person of African ancestry could claim citizenship in the United States, and therefore Scott could not bring suit in federal court under diversity of citizenship rules. Scott's temporary residence in free territory outside Missouri did not bring about his emancipation, because the Missouri Compromise, which made that territory free by prohibiting slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, was unconstitutional because it "deprives citizens of their [slave] property without due process of law".

Although Chief Justice Roger B. Taney had hoped to settle issues related to slavery and congressional authority by this decision, it aroused public outrage, deepened sectional tensions between the northern and southern states, and hastened the eventual explosion of their differences into the American Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the post-Civil War Reconstruction Amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments—nullified the decision. The Scotts were manumitted by private arrangement in May 1857. Dred Scott died of tuberculosis a year later.

Life

[edit]

Dred Scott was born into slavery c. 1799 in Southampton County, Virginia. It is not clear whether Dred was his given name or a shortened form of Etheldred.[1]

In 1818, Dred was taken by Peter Blow and his family, with their five other slaves, to Alabama, where the family ran an unsuccessful farm in a location near Huntsville. This site is now occupied by Oakwood University.[2][3][4] The Blows gave up farming in 1830 and moved to St. Louis, Missouri.[5]

Dred Scott was sold to Dr. John Emerson, a surgeon serving in the United States Army, who planned to move to Rock Island, Illinois. Blow died in 1832, and historians debate whether Scott was sold to Emerson before or after Blow's death. Some believe that Scott was sold in 1831, while others point to a number of enslaved people in Blow's estate who were sold to Emerson after Blow's death, including one with a name given as Sam, who may be the same person as Scott.[6] After Scott learned of this sale, he attempted to run away. His decision to do so was spurred by a distaste he had developed for Emerson. Scott was temporarily successful in his escape as he, much like many other runaway slaves during this time period, "never tried to distance his pursuers, but dodged around among his fellow slaves as long as possible". Eventually, he was captured in the "Lucas Swamps" of Missouri and taken back.[7]

As an army officer, Emerson moved frequently, taking Scott with him to each new army posting. In 1833, Emerson and Scott went to Fort Armstrong, in the free state of Illinois. In 1837, Emerson took Scott to Fort Snelling, in what is now the state of Minnesota and was then in the free territory of Wisconsin. There, Scott met and married Harriet Robinson, a slave owned by Lawrence Taliaferro. The marriage was formalized in a civil ceremony presided over by Taliaferro, who was a justice of the peace. Since slave marriages had no legal sanction, supporters of Scott later noted that this ceremony was evidence that Scott was being treated as a free man. But Taliaferro transferred ownership of Harriet to Emerson, who treated the Scotts as his slaves.[5]

Dr. Emerson was transferred to Fort Jesup in Louisiana in 1837, leaving the Scott family behind at Fort Snelling and leasing them out (also called hiring out) to other officers.[5] In February 1838, Emerson met and married Eliza Irene Sanford in Louisiana, whereupon he sent for the Scotts to join him, only to be reassigned to Fort Snelling later that year.[1][8] While on a steamboat heading north on the Mississippi River, north of Missouri, Harriet Scott gave birth to their first child, whom they named Eliza.[1] They later had a daughter, Lizzie. They also had two sons, but neither survived past infancy.[5]

The Emersons and Scotts returned to Missouri, a slave state, in 1840. In 1842, Emerson left the Army. After he died in the Iowa Territory in 1843, his widow Irene inherited his estate, including the Scotts. For three years after Emerson's death, she continued to lease out the Scotts as hired slaves. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his and his family's freedom, offering $300 ($10,173 adjusted for inflation).[9] Irene Emerson refused the offer. Scott and his wife separately filed freedom suits to try to gain their freedom and that of their daughters. The cases were later combined by the courts.[10]

Dred Scott v. Sandford

[edit]Summary

[edit]The Scotts' cases were first heard by the Missouri circuit court. The first court upheld the precedent of "once free, always free". That is, because the Scotts had been held voluntarily for an extended period by their owner in a free territory, which provided for slaves to be freed under such conditions, the court ruled, they had gained their freedom. The owner appealed. In 1852 the Missouri supreme court overruled this decision, on the basis that the state did not have to abide by free states' laws, especially given the anti-slavery fervor of the time. It said that Scott should have filed for freedom in the Wisconsin Territory.

Scott ended up filing a freedom suit in federal court (see below for details), in a case that he appealed to the US Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that African descendants were not U.S. citizens and had no standing to sue for freedom. It also ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. This was the last in a series of freedom suits from 1846 to 1857, that began in Missouri courts, and were heard by lower federal district courts. The US Supreme Court overturned the earlier precedents and established new limitations on African Americans.

In detail

[edit]In 1846, having failed to purchase his freedom, Scott filed a freedom suit in St. Louis Circuit Court. Missouri precedent, dating to 1824, had held that slaves freed through prolonged residence in a free state or territory, where the law provided for slaves to gain freedom under such conditions, would remain free if returned to Missouri. The doctrine was known as "Once free, always free". Scott and his wife had resided for two years in free states and free territories, and his eldest daughter had been born on the Mississippi River, between a free state and a free territory.[11]

Dred Scott was listed as the only plaintiff in the case, but his wife, Harriet, had filed separately and their cases were combined. She played a critical role, pushing him to pursue freedom on behalf of their family. She was a frequent churchgoer, and in St. Louis, her church pastor (a well-known abolitionist) connected the Scotts to their first lawyer. The Scott children were around the age of ten when the case was originally filed. The Scotts were worried that their daughters might be sold.[12]

The Scott v. Emerson case was tried by the state in 1847 in the federal-state courthouse in St. Louis. Scott's lawyer was originally Francis B. Murdoch and later Charles D. Drake. As more than a year elapsed from the time of the initial petition filing until the trial, Drake had moved away from St. Louis during that time. Samuel M. Bay tried the case in court.[8] The verdict went against Scott, as testimony that established his ownership by Mrs. Emerson was ruled to be hearsay. But the judge called for a retrial, which was not held until January 1850. This time, direct evidence was introduced that Emerson owned Scott, and the jury ruled in favor of Scott's freedom.

Irene Emerson appealed the verdict. In 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court struck down the lower court ruling, arguing that, because of the free states' anti-slavery fervor was encroaching on Missouri, the state no longer had to defer to the laws of free states.[13] By this decision, the court overturned 28 years of precedent in Missouri. Justice Hamilton R. Gamble, who was later appointed as governor of Missouri, sharply disagreed with the majority decision and wrote a dissenting opinion.

In 1853, Scott again sued for his freedom, this time under federal law. Irene Emerson had moved to Massachusetts, and Scott had been transferred to Irene Emerson's brother, John F. A. Sanford. Because Sanford was a citizen of New York, while Scott would be a citizen of Missouri if he were free, the Federal courts had diversity jurisdiction over the case.[14] After losing again in federal district court, the Scotts appealed to the United States Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford. (The name is spelled "Sandford" in the court decision due to a clerical error.)

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion. Taney ruled, with three major issues, that:

- Any person descended from Africans, whether slave or free, is not a citizen of the United States, according to the U.S. Constitution.

- The Ordinance of 1787 could not confer either freedom or citizenship within the Northwest Territory to non-white individuals.

- The provisions of the Act of 1820, known as the Missouri Compromise, were voided as a legislative act, since the act exceeded the powers of Congress, insofar as it attempted to exclude slavery and impart freedom and citizenship to non-white persons in the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase.[15]

The Court had ruled that African Americans had no claim to freedom or citizenship. Since they were not citizens, they did not possess the legal standing to bring suit in a federal court. As slaves were private property, Congress did not have the power to regulate slavery in the territories and could not revoke a slave owner's rights based on where he lived. This decision nullified the essence of the Missouri Compromise, which divided territories into jurisdictions either free or slave. Speaking for the majority, Taney ruled that because Scott was considered the private property of his owners, he was subject to the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting the taking of property from its owner "without due process".[16]

Rather than settling issues, as Taney had hoped, the court's ruling in the Scott case increased tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in both North and South, further pushing the country toward the brink of civil war. Ultimately after the Civil War, on July 9, 1868, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution settled the issue of Black citizenship via Section 1 of that Amendment: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside ..."[17]

Abolitionist aid to Scott's case

[edit]

Scott's freedom suit before the state courts was backed financially by Peter Blow's adult children, who had turned against slavery in the decade since they sold Dred Scott. Henry Taylor Blow was elected as a Republican Congressman after the Civil War, Charlotte Taylor Blow married the son of an abolitionist newspaper editor, and Martha Ella Blow married Charles D. Drake, one of Scott's lawyers who was elected by the state legislature as a Republican US Senator. Members of the Blow family signed as security for Scott's legal fees and secured the services of local lawyers. While the case was pending, the St. Louis County sheriff held these payments in escrow and leased Scott out for fees.

In 1851, Scott was leased by Charles Edmund LaBeaume, whose sister had married into the Blow family.[5] Scott worked as a janitor at LaBeaume's law office, which was shared with lawyer Roswell Field.[19]

After the Missouri Supreme Court decision ruled against the Scotts, the Blow family concluded that the case was hopeless and decided that they could no longer pay Scott's legal fees. Roswell Field agreed to represent Scott pro bono before the federal courts. Scott was represented before the U.S. Supreme Court by Montgomery Blair. (Blair later served in President Abraham Lincoln's cabinet as Postmaster General.) Assisting Blair was attorney George Curtis. His brother Benjamin was an Associate Supreme Court Justice and wrote one of the two dissents in Dred Scott v. Sandford.[5]

In 1850, Irene Emerson remarried and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts. Her new husband, Calvin C. Chaffee, was an abolitionist. He was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1854 and fiercely attacked by pro-slavery newspapers for his apparent hypocrisy in owning slaves.

Given the complicated facts of the Dred Scott case, some observers on both sides raised suspicions of collusion to create a test case. Abolitionist newspapers charged that slaveholders colluded to name a New Yorker as defendant, while pro-slavery newspapers charged collusion on the abolitionist side.[20]

About a century later, a historian established that John Sanford never legally owned Dred Scott, nor did he serve as executor of Dr. Emerson's will.[19] It was unnecessary to find a New Yorker to secure diversity jurisdiction of the federal courts, as Irene Emerson Chaffee (still legally the owner) had become a resident of Massachusetts. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Roswell Field advised Dr. Chaffee that Mrs. Chaffee had full powers over Scott.[20] However, Sanford had been involved in the case since the beginning, as he had secured a lawyer to defend Mrs. Emerson in the original state lawsuit before she married Chaffee.[10]

Freedom

[edit]

Following the ruling, the Chaffees deeded the Scott family to Republican Congressman Taylor Blow, who manumitted them on May 26, 1857. Scott worked as a porter in a St. Louis hotel, but his freedom was short-lived; he died from tuberculosis in September 1858.[21][22] He was survived by his wife and his two daughters.

Scott was originally interred in Wesleyan Cemetery in St. Louis. When this cemetery was closed nine years later, Taylor Blow transferred Scott's coffin to an unmarked plot in the nearby Catholic Calvary Cemetery, St. Louis, which permitted burial of non-Catholic slaves by Catholic owners.[23] Some of Scott's family members have claimed that he was a Catholic.[24] A local tradition later developed of placing Lincoln pennies on top of Scott's gravestone for good luck.[23]

Harriet Scott was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Hillsdale, Missouri. She outlived her husband by 18 years, dying on June 17, 1876.[5] Their daughter, Eliza, married and had two sons. Their other daughter, Lizzie, never married but, following Eliza's early death, helped raise Eliza's sons (Lizzie's nephews). One of Eliza's sons died young, but the other married and has descendants, some of whom still live in St. Louis as of 2023,[25] including Lynne M. Jackson, Scott's great-great-granddaughter, who led the successful effort to install a new towering memorial at Dred Scott's grave at Calvary Cemetery on September 30, 2023. [18]

Prelude to Emancipation Proclamation

[edit]The newspaper coverage of the court ruling, and the 10-year legal battle raised awareness of slavery in non-slave states. The arguments for freedom were later used by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. The words of the decision built popular opinion and voter sentiment for his Emancipation Proclamation and the three constitutional amendments ratified shortly after the Civil War: The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, abolishing slavery, granting former slaves' citizenship, and conferring citizenship to anyone born in the United States and "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" (excluding subjects to a foreign power such as children of foreign ambassadors).[26]

Legacy

[edit]- 1957: Scott's gravesite was rediscovered, and flowers were put on it in a ceremony to mark the centennial of the case.[27]

- 1971: Bloomington, Minnesota dedicated 48 acres as the Dred Scott Playfield.[28]

- 1977: The Scotts' great-grandson, John A. Madison, Jr., an attorney, gave the invocation at the ceremony at the Old Courthouse (St. Louis, Missouri) for the dedication of a National Historic Marker commemorating the Scotts' case.[27]

- 1997: Dred and Harriet Scott were inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[29]

- 1999: A cenotaph was installed for Harriet Scott at her husband's grave to commemorate her role in seeking freedom for them and their children.[27]

- 2001: Harriet and Dred Scott's petition papers were displayed at the main branch of the St. Louis Public Library, following discovery of more than 300 freedom suits in the archives of the circuit court.[27]

- 2006: Harriet Scott's grave site was proven to be in Hillsdale, Missouri and a biography of her was published in 2009.[27] A new historic plaque was erected at the Old Courthouse to honor the roles of both Dred and Harriet Scott in their freedom suit and its significance in U.S. history.[27]

- May 9, 2012: Scott was inducted into the Hall of Famous Missourians; a bronze bust by sculptor E. Spencer Schubert is displayed in the Missouri State Capitol Building.[30]

- June 8, 2012: A bronze statue of Dred and Harriet Scott was erected outside of the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis, MO, the site where their case was originally heard.[31]

- March 6, 2017, the 160th anniversary of the Dred Scott Decision: On the steps of the Maryland State House next to a statue of Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, his great-great-grandnephew Charlie Taney apologized on his behalf to Scott's great-great-granddaughter Lynne Jackson and all African-Americans "for the terrible injustice of the Dred Scott decision".[32] During the ceremony, Kate Taney Billingsley, Charlie Taney's daughter, read lines regarding the court's decision from the play A Man of His Time.[33]

Accounts of Scott's life

[edit]Shelia P. Moses and Bonnie Christensen wrote I, Dred Scott: A Fictional Slave Narrative Based on the Life and Legal Precedent of Dred Scott (2005).[27] Mary E. Neighbour, wrote Speak Right On: Dred Scott: A Novel (2006).[27] Gregory J. Wallance published the novel Two Men Before the Storm: Arba Crane's Recollection of Dred Scott and the Supreme Court Case That Started the Civil War (2006).[27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ 2 died during infancy

References

[edit]- ^ a b c VanderVelde, Lea (January 20, 2009). Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery's Frontier. Oxford University Press, US. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-0199710645.

- ^ "Dred Scott, And Oakwood University". Deepfriedkudzu.com. February 22, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ "A catalyst for Civil War after suing for freedom, slave Dred Scott once lived in Huntsville". Blog.al.com. April 15, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ "Huntsville, Alabama | G.I.S. Division | Historic Markers Site". January 19, 2015. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dred Scott Case, 1846–1857". Missouri Digital Heritage. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ^ For a longer discussion, see Ehrlich, 1979. chapter 1, or more recently see, Swain, 2004. p. 91

- ^ "U-M Weblogin". Cincinnati Enquirer. ProQuest 881879875.

- ^ a b Ehrlich, Walter (2007). They Have No Rights: Dred Scott's Struggle for Freedom. Applewood Books. pp. 20, 25.

- ^ "Dred Scott's fight for freedom: 1846–1857". Africans in America: People & Events. PBS. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Fehrenbacher, Don Edward (2001). The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195145885.[page needed]

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (2007). "Scott v. Sandford: The Court's Most Dreadful Case and How it Changed History" (PDF). Chicago-Kent Law Review. 82 (3): 3–48.

- ^ "Multimedia | The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". Gilderlehrman.org. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ Scott v. Emerson, 15 Mo. 576, 586 (Mo. 1852) Archived December 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved August 20, 2012. The Emersons were represented by Hugh A. Garland and Lyman Decatur Norris.

- ^ Randall, J. G., and David Donald. A House Divided. The Civil War and Reconstruction. 2nd ed. Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1961, pp. 107–114.

- ^ "Decision of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott Case". The New York Daily Times. New York. March 7, 1857. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Frederic D. Schwarz Archived December 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine "The Dred Scott Decision", American Heritage, February/March 2007.

- ^ Carey, Patrick W. (April 2002). "Political Atheism: Dred Scott, Roger Brooke Taney, and Orestes A. Brownson". The Catholic Historical Review. 88 (2). The Catholic University of America Press: 207–229. doi:10.1353/cat.2002.0072. ISSN 1534-0708. S2CID 153950640.

- ^ a b "New memorial at Dred Scott's gravesite in St. Louis is 'honorable' marker of his legacy". September 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Ehrlich, Walter (September 1968). "Was the Dred Scott Case Valid?". The Journal of American History. 55 (2): 256–265. doi:10.2307/1899556. JSTOR 1899556.

- ^ a b Hardy, David T. (2012). "Dred Scott, John San(d)ford, and the Case for Collusion" (PDF). Northern Kentucky Law Review. 41 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2015.

- ^ "Harriet Robinson Scott - Historic Missourians - The State Historical Society of Missouri". Shsmo.org. Archived from the original on November 25, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Axelrod, Alan (2008). Profiles in Folly: History's Worst Decisions and why They Went Wrong. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-1402747687.

- ^ a b O'Neil, Time (March 6, 2007). "Dred Scott: Heirs to History" (PDF). St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Goldstein, Dawn Eden. "Tweet". Twitter. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Jonathan M. Pitts, Tribune News Service. "Taney, Dred Scott families reconcile 160 years after decision". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ Paul Finkleman, Dred Scott v. Sandford: A Brief History with Documents, Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, pp. 7–9, Retrieved February 26, 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Arenson, Adam (2014). "Dred Scott versus the Dred Scott Case: The History and Memory of a Signal Moment in American Slavery, 1857–2007". In Konig, David Thomas; Finkelman, Paul; Bracey, Christopher Alan (eds.). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Ohio University Press. pp. 25–46. ISBN 978-0821443286.

- ^ "Welcome to Dred Scott Playfields" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Griffin, Marshall. "Dred Scott inducted to Hall of Famous Missourians". Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ O'Leary, Madeline. "Dred and Harriet Scott statue ready for debut". stltoday.com. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ "From a descendant of Roger Taney to a descendant of Dred Scott: I'm sorry". Washington Post. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Billingsley, Kate T. (March 2, 2017). "Historic Healing & Reconciliation 160th Annversary [sic] Of Dred Scott Decision Monday March 6, 2017". Kate Taney Billingsley. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Allen, Austin (2006). Origins of the Dred Scott Case: Jacksonian Jurisprudence and the Supreme Court, 1837–1857. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0820326535.

- Ehrlich, Walter. They have no rights: Dred Scott's struggle for freedom. No. 9. Praeger Pub Text, 1979.

- Fehrenbacher, Don E. (1978). The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195024036.

- Napolitano, Andrew (2009). Dred Scott's Revenge: A Legal History of Race and Freedom in America. Thomas Nelson. p. 288. ISBN 978-1418575571.

- Shurtleff, Mark (2009). Am I Not a Man? The Dred Scott Story. Orem, UT: Valor Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1935546009.

- Swain, Gwenyth (2004). Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family's Struggle for Freedom. Saint Paul, MN: Borealis Books. ISBN 978-0873514835.

- Tsesis, Alexander (2008). We Shall Overcome: A History of Civil Rights and the Law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300118377.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (January 2019) |

- Dred and Harriet Scott in Minnesota in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

- "St. Louis Circuit Court Records", A collection of images and transcripts of 19th century Circuit Court Cases in St. Louis, particularly freedom suits, including suits brought by Dred and Harriet Scott. A partnership of Washington University and Missouri History Museum, funded by an IMLS grant

- "Freedom Suits", African-American Life in St. Louis, 1804–1865, from the Records of the St. Louis Courts, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, National Park Service

- Revised Dred Scott Case Collection

- Christyn Elley, "Biography of Dred Scott", Missouri State Archives

- Full text of the Dred Scott v. Sandford, Supreme Court decision Findlaw

- Dred Scott v. Sandford and related resources, Library of Congress

- "Dred Scott Chronology", Washington University in St. Louis

- Dred Scott Heritage Foundation

- Dred Scott - Findagrave, including pictures depicting the old gravestone and the new memorial

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Works by Dred Scott at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Dred Scott at the Internet Archive