East Kent Light Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

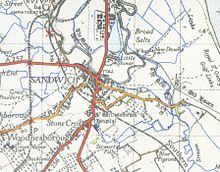

The East Kent Light Railway was part of the Colonel Stephens group of cheaply built rural light railways in England. Holman Fred Stephens was engineer from its inception, subsequently becoming director and manager. The line ran from Shepherdswell to Wingham (Canterbury Road) Station with a branch from Eastry through Poison Cross to Richborough Port. Built primarily for colliery traffic within the Kent Coalfields, the line was built with many spurs and branches to serve the mines, with cancelled plans to construct extensions to several others. The success of Tilmanstone colliery allowed the main line of the railway to continue operation until 1986. A remainder of the line became the East Kent Railway, a heritage railway, in 1987.

History

[edit]Pre WW1

[edit]The East Kent Light Railways (official title) was originally conceived before the First World War as a network of lines in East Kent linking at least nine proposed collieries in the newly discovered Kent coalfield to a new coal port at Richborough Port. In order to exploit the coal measures under the rural Kent countryside collierries needed to be built and then shafts sunk, and the use of the rural roads to achieve this caused great damage, so the railways offered a potential benefit during the construction phase, though clearly the long term benefit would be in taking the produced coal to markets.

It was originally called the East Kent Mineral (Light) Railways[1] when first proposed in 1909. The progenitors were Christopher Solley of "Sandwich Haven Wharves Syndicate" at Sandwich, who dreamed of his town becoming a great port again, Arthur Burr of "Kent Coal Concessions Ltd", the original promoter of the Kent coalfield.[2] and the "St Augustines Links Ltd", which was meant to have laid out a golf course.

The proposed route of the East Kent Mineral Railway was announced in 1910,[3] as follows :

- Railway 1 of 10.25 miles was from Sheperdswell to the banks of the River Stour on the Stonar side of Sandwich via Tilmanstone and Woodnesborough collieries.

- Railway 2 of 11.5 miles from Canterbury West via Sturry, Fordwich, Wickham, Ingham, Wingham (Colliery), Staple, Ash and then to join Railway No 1 near Sandwich.

- Railway 3 of 0.5 mile was a branch to joint Railways 1 and 2 near Eastry.

- Railway 4 of 2.5 miles was a branch from Railway 1 to Guilford colliery linking it with Tilmanstone.

- Railway 5 of 4 miles was a branch from Railway 1 at Eythorne to the brickfields near Northbourne Rectory

- Railway 6 of 2 miles was a branch from Railway 2 to an area between Goodnestone and Sandwich where test borings had shown coal

- Railways 7 to 10 were minor loops and branches 'to facilitate traffic on the principal lines near Wingham, Eythorne, Sandwich and Sheperdswell'

In October 1910 it was announced that the line from Canterbury to Wingham would not be built due to 'serious objections from the War Office and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners'.[4] Plans for Railway No 3 and the Eastern part of Railway No 5 were also withdrawn. There were numerous later minor revisions to the course of the railway taking into account objections.

A temporary line from Sheperdswell to Tilmanstone was put in place during the autumn of 1911, saving some £200 a week being charged to the colliery for road repairs.[5] This was replaced by a permanent line starting in June 1912.[6] A double-track tunnel was bored at Golgotha near Eythorne, and Colonel Stephens did not remove all the material from the double bore as a "temporary" economy. (The railway was single-track throughout.) The line to Tilmanstone and the branch to Guilford colliery (Railway No 4) were completed by October 1912.[7] The first passenger train (a single coach carrying shareholders etc attending the AGM), ran from Sheperdswell to Tilmanstone Colliery on 27 November 1912.[8]

First coal was raised at Tilmanstone in mid-1913 and proved of high quality from a 5 foot vein. By July 1913 the temporary rail track had been extended to Wingham to serve Wingham Colliery, and later that year work started on the extension of the line from Wingham Colliery towards Stodmarsh.[9] The sinking of the shafts at Wingham Colliery in 1913 was interrupted by flooding, lack of finance and then WW1.

However in most of the collieries there were problems with managing water while sinking the shafts, and shortly after Tilmanstone reached full production in 1914, World War One resulted in changed priorities. Work on the other mines being suspended, with the EKLR only serving just the one productive mine. Some equipment from Wingham Colliery was requisitioned during WW1 – two boilers went to Tilmanstone Colliery. There was some progress on the railway during the war with passenger services from Shepherdswell to Wingham started on 16 October 1916.

Post WW1

[edit]After WW1 there were attempts to continue work on the as yet unopened collieries along the railway, but none of these succeeded. Work on sinking the shafts at Guilford colliery ceased in 1921. Wingham Colliery shafts never reached much depth and the Wingham colliery site saw its last train in 1921 when surplus equipment was sold off. Woodnesborough colliery had its surface buildings built but never got as far as sinking shafts before war broke out, and work never resumed, though the site was taken over by Hammill Brick Company in 1927 and so the branch connecting it to the East Kent Light Railway was used for this purpose.

In 1920 the railway reached Wingham Town, whereupon the original "Wingham" terminus was renamed "Wingham Colliery", although the colliery, which was served by a 1/2 mile spur to the south never produced any coal. Slightly to the West of the Wingham Colliery station was a short spur off to the works of the Wingham Engineering Company (who in 1934 bought the Wingham Colliery site). The extension of the line continued until it reached Wingham Canterbury Road in 1924/1925. Substantial work on the extension of the line beyond Wingham had been completed by January 1925, when it was reported that the land for the line had been purchased and fenced, and about 50% of the earthworks had been completed between Wingham and within half a mile of Stodmarsh.[10] Hopes of completing extensions were raised when the Southern Railway invested £44,000 in discounted shares (£220,000 at par) in 1926,[11] but dashed when it lost interest (although remaining friendly and having directors on the Board).

The lines from Eastry Junction to Sandwich and from Wingham Colliery to Wingham Canterbury Road were inspected in March 1925 and both were passed for goods and passenger traffic.[12] The passenger service – initially Saturdays only – from Eastry to Sandwich Road started on 18 April 1925, and lasted until 31 October 1928.

The extension of the railway to the quays on the River Stour was finally achieved in 1928, although it relied on a temporary bridge instead of the swing bridge authorised. The project to rejuvenate the port at Richborough never came to fruition, and with only one of the planned collieries open, the need to ship coal from the Kent coalfields via the port didn't materialise. The only known movements at Richborough Port were the importation of timber for pit-props at Tilmanstone Colliery, and the export of some coal from Snowdown. Richborough Port was a failure, and the EKLR became a truly rural railway with a heavy coal flow for a few miles only at one end between the working colliery at Tilmanstone and the SECR main line at Shepherdswell. The colliery company objected to its rates, and opened an aerial ropeway in competition to the Eastern Arm of Dover Harbour in 1930. This was a failure, as the coal did not sell on the export market and mostly found a market in London. However, it was only dismantled in 1952.

On tickets etc. and in publicity the railway referred to itself as the "East Kent Railway", which was technically incorrect. The company logo was "EKR" (no heraldry).

Colonel Stephens died in 1931, and was succeeded as General Manager by his long-time assistant and life partner, W.H. Austen, who served until nationalisation. His period in office initially saw a tidying-up and some rationalisation of activities, together with a badly needed rebuilding of the engine shed finished in 1938.

WW2

[edit]The Colonel Stephens Society holds a record in their archives of the EKLR during WW2, from which some of the following are extracted.[13]

On about 20 May 1940 No 97 MU (Maintenance Unit) of the Royal Air Force took over Staple Station. The station was open to through trains but closed to passengers and goods, unless they were for (or from) the RAF. Operational records suggest this was for the creation of a munitions store and munitions were transferred to and from Bekesbourne Aerodrome and to Larkhill. From the end of May until 22 June guard duties at the munitions dump were carried out by the Local Defence Volunteers. The arrangements were only temporary as in August 1940 the RAF departed and the station was returned back to the East Kent Light Railway.

On 8 September 1940 three "super heavy batteries of artillery" entered the railway, with 0-6-0 tender engines hauling 82 ton 9.2 inch rail-mounted guns. Rail-guns were deployed at many locations in the South of england, and their purpose was to bombard any German invasion forces - and to strike occupied British airfields. The guns and their locomotives were located in the sidings at Sheperdswell, Eythorne and Staple stations, also at Poulton sidings (between Staple and Ash stations). Military records indicate that in October 1940 No.5 super heavy battery were at Sheperdswell equipped with 2 of 12" rail howitzers, and No.37 super heavy battery were at Eythorne with another 2 of 12" rail howitzers, and No.12 super heavy battery had one 12" rail howitzer at Staple Halt and another at Poulton Farm sidings. Although the EKLR account talks of the 9.2" rail gun, it is clear that for the bulk of the time the guns on the line were the six 12" howitzers.

Firing practice took place on several occasions with live shells. In the first live firing at Sheperdswell considerable damage occurred to windows, roofs and doors of adjacent buildings due to the blast wave. Coaching stock in Sheperdswell station 100 yards away had its windows damaged, and on future occasions was moved out of harms way, and all staff ordered out of the rail sheds and workshops. Rail guns were normally fired only on specially built rail spurs away from buildings. These spurs were equipped with anchorages for securing the gun carriages via multiple one inch cables, as the recoil from firing live shells was substantial. These large rail mounted guns remained on the railway until December 1944.

During the war the former Hammill brickworks site and equipment was adapted for drying damp grain, and so the rail spur was used to deliver 100 tons of coal a week to the dryers - the opposite direction to the original planned use.

During the war Tilmanstone continued coal production, and around 280,000 tons of coal a year were shipped out by rail, with the EKLR locos totalling about 25,000 miles per year (plus the WD locos ran a total of 10,349 miles while on the line). There was only one direct hit on the line, by a high explosive bomb on 19 September 1940 on an embankment on the Richborough line. The hole was filled in, the track section replaced, and the railway was back into normal service 12 hours later.

Post WW2

[edit]After an extended period of increasing decrepitude, the final passenger service of two trains each way on weekdays (down from three) ran on 30 October 1948 following the nationalisation of British Railways. Freight services from Eastry to Port Richborough ceased officially on 27 October 1949 (although no train had run there for some time and track was missing on the river bridge), services west of Eastry ceased on 25 July 1950 and services North of Tilmanstone Colliery ceased on 1 March 1951.

The track on the 'main-line' was lifted in 1958, one of the last class O1 locos, no 31258 of 1894, was used.[14] This left only the line from Sheperdswell to Tilmanstone Colliery via the Golgotha tunnel. Locomotive 31258 was also used on a railtour in 1959 that covered the remaining Sheperdswell to Tilmanstone line. Class O1 was typical of the locomotives used on Kent branch lines in the 1950s, and the sole survivor of this class (BR 31065) can be found on the Bluebell Railway.

Colliery traffic continued until 1 March 1984 when Tilmanstone colliery ceased production due to the miners' strike. The coal mine did eventually re-open and produced some coal until closure in 1986, but the line was not used again. In mid-October 1986 the miners voted to accept the closure of the Tilmanstone coal mine, and the disused rail line to the pit was officially closed on 24 October 1986.

EKLR at Port Richborough

[edit]The sources are vague and contradictory, and more research needs to be done.[15][16]

Before 1911, Richborough Port was known as "Sandwich Haven". There was a gravel pit (now a lake) and a quay on the Long Reach of the River Stour, used during the construction of the Admiralty Harbour at Dover by S. Pearson & Sons Co. This firm built a tramway, nicknamed "Pearson's Railway", from a junction with the SECR at Richborough Castle to the pit and to "Pearson's Quay" (also known as "Old Quay" or "Stonor Quay").

It is not known why the first coalfield promoters chose this place for a coal port instead of the more obvious Dover. However, before WW1 Dover was intended to be the harbour of refuge for the Royal Navy's Channel Fleet, and so it was apparently feared that there would be little room left for coal ships. Unfortunately, Krupp in Germany were already making steel cannon which could fire across the Channel by 1905, which ruled out any Royal Navy presence at Dover and made Richborough Port commercially rather pointless from the beginning.

The EKLR was authorised in 1911 to build a wharf on the later site of the War Office's "New Quay". This was to have been built by "St Augustine's Links Ltd", which initially planned a golf course but then diversified into planning a coal port and (via its subsidiary "Ebbsfleet Coal Syndicate") a coalmine. A boring in 1911 proved the coal seams to be too thin,[17] and the First World War stalled the port project. (The golf course was built, and is still there.)

The War Office took the port site over for an enormous transhipment camp during World War I, starting in 1916. The Royal Engineers abandoned Pearson's Railway and built a new line, with miles of siding trackage, from "Weatherlees Junction" on the SECR. The line ran along the north side of the derelict power station (pace recent publications, this line was not the same as the power station spur), crossed the Thanet to Sandwich road just north of the filling stations and arrived at the New Quay behind the sports ground at the site currently (2016) known as Discovery Park Enterprise Zone. It then ran down the east side of the road, crossed the Stonar Cut and split in two at the Red Lion pub, about where the entrance to the recycling plant now is. One branch crossed the road, and both ran along the road verges to army camps situated on the ground currently occupied by Discovery Park. The eastern branch also served Pearson's Quay.

Some anonymous army official coined the name "Richborough Port".

After the war, the SECR took over as temporary managers in 1919, until the port was sold to Pearson & Dorman Long (as the founding company had become) in 1925. It was in this period that the EKLR arrived, but the date is not known. Maps of 1918 do not show it. The War Office signed an agreement with the EKLR allowing junctions in June 1920, and an Army map in the Guildhall, Sandwich (discovered 1995) shows the EKLR in place. Hence it arrived between 1920 and 1922.

However, Lawson-Finch's book[18] gives documentary evidence showing construction on the line and bridges continuing until the first official goods traffic to Richborough Port in 1929. It may be that the EKLR laid its sidings at Richborough Port in isolation before anything could cross the bridge, in order to establish its presence. The mystery remains as to when the first actual train ran to Richborough Port.

After crossing its river bridge, the EKLR followed roughly the course of the Sandwich Bypass. Here were the goods sidings, with a track either side of the line.[19] Just before the roundabout on the old Thanet road it picked up the course of the former Pearson's railway and turned east to its passenger station. Then it crossed, in immediate succession, the western line to the camps, the road, the eastern line and a siding before a junction with the port's wharfside line at Pearson's Wharf. A spur ran north before the station for about 20yds to a junction with the port lines. This was the access route to New Quay, as well as to the SECR at Weatherlees (although there is no evidence that the EKLR ever exchanged traffic over this connection).

Some modern maps show the junction spur extending as far as the Red Lion crossing. This is probably erroneous,[20] but needs to be researched. The error may arise from the War Office having built the final stretch of line to New Quay that was authorised for the EKLR in 1911.

Pearson & Dorman Long wanted to build a steelworks at Richborough Port, with new towns to house the workers at Woodnesborough and Ash and using coal from its colliery at Betteshanger. It regarded the EKLR as a nuisance, and never encouraged it. However, the EKLR did ship coal for export from Snowdown from 1929 to the mid thirties, and pit props in the other direction.[21] All plans were abandoned at the Depression. A main line link for coal traffic was actually authorised for Dover Eastern Harbour via a tunnel under the castle in 1933, just about the time when it was finally realized that the Kent coalfield was a commercial failure.[22]

Before the Second World War, only certain buildings were being used for colliery machine maintenance and the port railway network had been, in effect, abandoned before being inherited by the National Coal Board in 1948. The EKLR river bridge had become unsafe before then, on an unknown date, and had had its rails removed.[20]

Stations on main line

[edit]All stations were basic, featuring a platform, seat, nameboard and hut (usually wooden). None had a toilet. Lighting was by one or two oil lamps on posts at staffed stations; unstaffed ones also initially, but it is unclear how long this was kept up.

Mileages in miles and chains, from Shepherdswell for the main line and Eastry for the branch.[23]

Stations or sidings served:[24]

- Shepherdswell railway station (EKLR) 0:00. (Railway headquarters. Terminus next to the SECR main line station. Had a dead-end spur to the platform but no loop, company offices in wooden scout-hut, public telephone in the station hut, round metal archive store initially intended as waiting-room, two-track goods yard and a brick ex-garage near the offices described as a "tool pattern store".)

- North Bank Siding.

- Eythorne. 1:52. (Had a siding, bypass loop leading on to Tilmanstone Colliery branch and a brick hut.)

- Elvington Halt. 2:32. Was "Tilmanstone Colliery Halt", 1916 to 1927, when the platform was rebuilt in brick.[25] (Access from Elvington was via a footpath called "Burgess Hill". The site survives as a small wood.)

- Knowlton Halt. 3:42. (west of Thorntonhill Cottages, south of level crossing.)

- Hersden Siding. (near the following, on the other side of the crossing.)

- Eastry South. 5:17. (Opened in 1925. North of Heronden Road level crossing.)

- Eastry 5:52. (South of Selsdon Road bridge. Had a loop. A road block from the Second World War invasion scare is listed as leaving remains under the bridge.)[26]

- Woodnesborough 6:45. (actually in the hamlet of Drainless Drove. West of Hammill Road level crossing. Had a siding, loading dock and water tank. Opened as "Woodnesborough Colliery". Now occupied by a mushroom farm.)

- Moat Farm Siding (no passengers).

- Ash Town. 8:00 (by Meadow Cottage, west of footpath from Pudding Lane. The station entrance is marked by a cherry tree. Ash was never a town, but would have become one if the steelworks at Richborough Port had been built. In 1916, the footpath to the village was described as 'in very bad condition...over run with cattle', the railway company having asked for it to be made up.[27])

- Poulton Farm Siding (no passengers).

- Staple 8:66. (west of Durlock Road crossing, just south of farm entrance. The most important station for goods. Had a brick hut, loop and four sidings and water tank with windpump. Also known as "Staple & Ash".)

- Wingham Colliery. 10:29. (north side of Staple Road, east of Dambridge Farm entrance, where new wood boundary meets road.)

- Wingham Engineering Siding.

- Wingham Town. 10:65. (E. of Adisham road level crossing, SE corner of cemetery, where there is a private car parking place. Before the extension to Canterbury Road it had a loop and siding. The place was a town in the Middle Ages.)

- Wingham (Canterbury Road). 11:27. (west of crossing, now a ploughed field. The low embankment east of the crossing is visible. The goods spur was on this side of the road, with the circular corrugated iron goods shed identical to the archive shed at Shepherdswell. There was no loop; the nearest was at Staple.)

There is anecdotal evidence that passenger trains stopped unofficially on request at the private farm sidings at Ash, also that goods vans were left loose on the running line between stations overnight for farmers to load.[28]

Shepherdswell, Eythorne, Eastry, Woodnesborough, Staple and Wingham Canterbury Road were staffed. Otherwise tickets were sold by the train guard.[29]

Richborough Port Branch

[edit]- Poison Cross. 00:32. (The OS showed it in the corner between Foxborough Hill and Drainless Road, but this is erroneous. It was east of Foxborough Hill, and had a loop and siding. No hut. The mythical story is that the monks of a monastery here poisoned each other off. The name may have been to do with fishes -"poissons" in French- instead.)

- Roman Road. 1:53. Known as "Roman Road (Woodnesborough)" before 1938. The name is a puzzle; published sources claim it was because the road it was on was Roman. It wasn't. (South of the crossing on the Sandwich to Woodnesborough road, and nearer the latter than Woodnesborough station. No hut. Ploughed out.)

- Sandwich Road. 2:41. (The passenger terminus, at the south side of Ash Road. British railways had a tradition of including "Road" in station names to warn travellers that the place served was not within reasonable walking distance. Had a padlocked portable cabin containing a telephone for goods customers to order collection. At the roundabout where the Sandwich bypass now crosses that road. When it was open there was nothing larger than a sheep anywhere near, and the passenger station earned most of its revenue from a roadside advertising billboard. Across the road was a loop.)

- Richborough Castle Siding. (Actually a short spur. Ran north from a junction loop with water tank, past the Roman amphitheatre, and fanned out as three tracks. The middle one mysteriously crossed Richborough Castle Road to terminate by the SECR line, but on a higher level so a junction was not possible. (Perhaps passenger exchange platforms were hoped for.) This was a public siding, and was the de facto branch terminus when the river bridge failed on an unknown date.)

- Richborough Port Sidings. A loop either side of the line. Now occupied by the bypass, between two roundabouts.

- Richboro Port Halt[30] 4:46.(Not to be confused with Richborough Castle Halt on SER Deal Branch); passenger services were never authorised over the rickety girder bridge across the River Stour. (By the west side of the old road just south of the roundabout at the north end of the Sandwich bypass. South-east corner of the triangular Pfizer's landscaped area.)

- Richborough Port – Pearson's Quay (also known as Old Quay, Stonar Quay or Lord Greville's Quay. He was the original landowner). The line continued across the road to join the port lines for access to this. (Supplanted by Pfizer's.)

- Richborough Port – New Quay. Accessed via a junction spur with the port lines where the main line turned east for Pearson's Quay. The quay is still there, but semi-derelict.)

Other branches and spurs

[edit]- North Bank Siding

At Shepherdswell a connecting spur was begun to a north-facing junction on the SECR main line but never finished (earthworks survive); instead, a very sharp curve to a junction was provided near the terminus. A siding was laid on the route of this abortive junction spur. Why this happened is a mystery. It was not as a result of hostility from the SECR, since they built a signal box at the site of the proposed junction.

- Tilmanstone Colliery Branch

There was initially a branch from Eythorne to Tilmanstone Colliery, which was then extended to re-join the main line north of Elvington at some stage (apparently illicitly, as the extension is not listed as authorised). The northern junction had a loop, but this and the junction was removed by 1926, leaving the line north of the colliery as a siding.[31] This north part vanished under the colliery waste tip some time after 1959, since it featured on the OS map of that year. The map in Lawson Finch, p132, has the colliery layout.

There was a platform at Tilmanstone Colliery for the use of miners' services, which operated from 1918 to 1929. This was described in timetables and on tickets as "Tilmanstone Colliery", thus causing obvious confusion with what later became Elvington Halt. This seems to have been deliberate, as the EKLR had no authority to run passenger services over the branch and issuing tickets was technically illegal. It should have contracted with the colliery company instead for these services, as was standard practice in coalfields elsewhere, instead of collecting a subsidy.[25]

- Guilford Colliery Branch

This was part of the original proposal of 1911, and ran south from Eythorne before curving east to the colliery site on the edge of Waldershare deer park (the colliery was named after the owner of the park). Despite a full set of colliery buildings being provided and three shafts started, the whole colliery was abandoned by its French owners in 1922 before it produced any coal. A section of the branch near the junction was used for stabling empty wagons before the track was lifted in 1937, and this section was re-laid in the Second World War as a place for stabling the rail-guns. The junction was with the bypass loop at Eythorne, facing Wingham.

Colonel Stephens is on record as stating that the Guilford branch was to have a passenger service once the colliery opened.[32]

- Eythorne Court Triangle

The Guilford branch was authorised with a triangular junction, and the earthworks for the Shepherdswell-facing curve were completed. There is one intriguing piece of evidence that the track for this triangular junction was briefly in use. Early photos of Locomotive No. 1 show it either facing Shepherdswell or Wingham; the EKLR had literally nowhere on its system where a locomotive could be turned except for this triangle! Not to be confused with another proposed triangle at Eythorne, from the proposed Deal line to Elvington to give a direct route from Canterbury to Deal. No work was done on this.

- Eastry Triangle

A triangular junction was authorised at Eastry, but not finished. The land for the curve allowing running from Wingham to Port Richborough was purchased and fenced, but no track was laid.

- Woodnesborough Colliery Spur

This ran from south-east of Woodnesborough station to Woodnesborough Colliery, which mine failed and became Hammill brickworks. This spur survived until 1951. A narrow-gauge line was parallel to it on the west, between brickworks and clay pit, and this still featured on the 1959 OS map, five years after the EKLR had been pulled up.

- Wingham Colliery Spur

This ran to Wingham Colliery, from a junction with loop just short of the original terminus and running south. The mine was a failure and the spur and loop were removed in 1921, but the buildings were taken over in 1947 by a successful animal feed merchants' now called "Grain Harvesters".[33] Apparently the EKLR did not own this spur, because it proposed its own spur in 1913.

Engine shed

[edit]The access line to this was from the western line of the goods yard, and threw off a carriage siding before bifurcating and running into the shed. There was a short spur parallel to the west side of the shed entrance, which was used for major refits in the open air. Next to this was an open-fronted shed.

The original shed was a rickety wooden structure with walls of Kentish weatherboarding and a tin roof. It fell into hopeless disrepair and was replaced in stages with a more substantial structure in corrugated asbestos with five brick smoke vents which was finished in 1937. This was pulled down by British Railways at an unknown date by 1953.

The workshop was a brick lean-to on the west side of the engine shed, and contained the following tools powered by a steam engine: Six-inch lathe, two-inch lathe, vertical drill, gear cutter, bench grindstone, forge and large grindstone (treadle powered).

The carpenter's shed was attached to the north end of this, but not to the engine shed. It had a circular saw powered by the workshop steam engine.

In between the engine shed and the carriage siding was a pair of wooden sheds side by side forming an "L". The western was an open-fronted fitter's store, and the eastern was the platelayers' headquarters.

The original locomotive water supply was by means of a row of tanks supplied from an open cistern under the wooden floor of the carpenter's shop. This grossly unsatisfactory arrangement (especially for the carpenter in winter) was replaced by a concrete covered reservoir in the woods, supplied from a well by means of a diesel pump and which fed two standpipes by gravity.

There seems to be no evidence for locomotive coaling facilities at Shepherdswell, and tenders were probably filled from the screens at Tilmanstone Colliery.

For the purposes of modelling, see "Shepherdswell" in Chapter 14 of Lawson Finch with the large-scale map on page 254, together with photo 40 in Mitchell & Smith. No published photograph seems to show the outside of the workshop.

Expansion plans

[edit]The original main line from Shepherdswell to Port Richborough was authorised in 1911, together with the Wingham branch (which became the main line in practice). Also authorised in 1911 and 1913, but not built, were the following lines:

- Eythorne to Ripple Colliery (proposed just north of Sutton church) via Little Mongeham. The colliery shaft was not even started.[34]

- Guilford to Maydensole Colliery near West Langdon. There had been a trial boring here, and buildings started.

- Guilford branch just short of the mine to Stonehall Colliery and a junction with the SECR. The last was yet another failed mine, just the other side of the SECR line from Lydden. The route ran diagonally down the steep slope of what is now the National Nature Reserve to a horseshoe bend in the valley.[35]

A massive expansion was authorised in 1920, but with little result:

- Woodnesborough Colliery to a coking plant at Snowdown Colliery. The owners of the latter were not interested.

- Little Mongeham on the Ripple Colliery spur to Deal. This was intended as a passenger line, with stops at Tilmanstone & Studdal (by Willow Wood), Little Mongeham, Great Mongeham, Sholden and a terminus at Deal Albert Road. A spur was proposed to the SECR line, facing north.

- Wingham to a junction with the SECR at the Hackington level crossing near Canterbury West, via Stodmarsh (not Ickham), thus making the Wingham branch the main line. Part was built to Wingham Canterbury Road, and this was the only outcome of the 1920 proposals. Maps of the 1920s show track laid as far as the proposed bridge over the Little Stour river near Wenderton Hoath, but if so it was never used. The company directors reported that 1.5m of earthworks had been constructed in 1925[32] The "Bartholomew" half-inch map of 1934 shows construction in progress to Wickhambreaux. The OS Twenty-Five Inch 1937 shows land fenced to the river. Passenger stops were proposed at Stodmarsh, Wickhambreux (on Wickham Court Lane), Elbridge, Fordwich, Old Park and Canterbury (Sturry Road).

- A spur from Wickhambreaux station to Wickhambreaux (or Stodmarsh) Colliery, proposed near Wickham Court Lane by the Chislet Colliery Co but not started.

- Coldred Junction on the Guilford branch to Drellingore in the Alkham Valley. This would have been heavily engineered, with two tunnels and a viaduct, and seems to be linked to the wish to fill the valley with coalminers' houses. (No mines were proposed there; the "Canterbury Coal Co" had a boring at Chilton in 1912 which showed that the seams were too thin to work.)[36] It would have crossed the SECR line just above the south portal of Lydden Tunnel, turned 180 degrees across the head of Lydden valley, ran down its west side and through a tunnel at Temple Ewell into Alkham Valley. There was to have been a reverse spur to Stonehall Colliery, crossing the A2 and SECR to get there.

- From the Deal line west of Little Mongeham to a brickworks (which promptly shut) at Telegraph Farm in Northbourne parish.

These schemes were prepared but not authorised:[37]

- Wingham Town to Goodnestone, 1911.

- Mongeham Colliery to Poison Cross, 1912.

- Maydensole line to the Dover harbour works contractor's line at Cherrytree Hole. The latter ran from Martin Mill on the SECR to Dover Eastern Docks. The cliffside portion was spoken for the proposed "Dover, St Margarets Bay & Martin Mill" electric railway. 1913.

- A spur to Wingham Colliery and to sidings on the other side of Staple Road, duplicating the coal company's spur already in place. 1913.

- Wickhambreux via Gore and Sturry to a coal jetty on Plumpudding Island west of Birchington, with spurs enabling SECR to run from Canterbury to Birchington and Herne Bay, 1920. This was in conjunction with the "Birchington Development Co", which proposed to convert that rather louche village resort into a fully fledged town (with no success).[38]

- Roman Road to SR at Sandwich, 1927.

- To Chislet Colliery and SR, 1927.

- Extension of the Richborough Castle siding to a barge quay on the River Stour by the SECR river bridge.

The Deal and Canterbury lines were re-authorised in 1931, the former being given a more direct route and the latter being shortened to run through Ickham, after the Southern Railway indicated its willingness to invest (which it initially did, but later chose to support local bus services instead after 1930).

The hostility of the owners of Richborough Port after 1925 led to a scheme for a coal dock north of Deal, near the Chequers pub. It would have taken half of the Royal Cinque Ports golf course.

Operations

[edit]Coal traffic

[edit]This was the railway's reason for existence.[39] It charged a fixed rate per ton for taking loaded coal wagons from Tilmanstone Colliery to Shepherdswell (no further) for switching onto the main line and for returning empties. Since the colliery possessed no locomotives, it also performed necessary shunting duties at the mine, including taking coal from the screens to the power station that ran the electric drainage pumps. Tonnage was over 200,000 after 1926. Rates agreed in 1932 were £0.0315 per ton to Shepherdswell, internal shunting at the colliery at £0.0126 per ton, 1,000 tons of free coal per year for railway use and £0.90 per ton over that. In return, the railway had to obtain all its coal from the colliery, and bad quality was to be a problem. The Southern Railway credited the EKLR £0.042 per ton of coal forwarded to them.

Export traffic from Snowdown Colliery to Richborough Port from 1929 to c1937 was greater than previously thought, peaking at c30,000 tons in 1933.

Tilmanstone coal was taken to customers elsewhere on the main line in the EKLR's own wagons. The major ones were Hammill brickworks and Wingham Engineering. Since Kent coal was friable and not suitable for all purposes, the railway also handled coal ordered from other coalfields. There was a coal merchants' located at Staple station.

Tilmanstone coal was also taken to Shepherdswell for the locomotives and for the steam engine running the lathes, etc. in the workshops. Kent coal was not very suitable for steaming, tending to break up and form dust, and this may account for anecdotal evidence that the engines sometimes had difficulty maintaining steam pressure while on service.

Other minerals

[edit]The nature of these are not identified in the records, but fire clay and gravel are noted as having been carried from time to time. Colliery spoil had some value in surfacing country paths and lanes. Sugar beet was listed as a "mineral", probably because it could be shipped loose and tipped.

Something called "Stonar Blue" was shipped from a pit at "Richborough" to potteries at Stoke-on-Trent. Published sources variously describe this as clay or flints, from the castle or the port, but it is ultimately uncertain what this was or where it came from.

General goods

[edit]This was between 5,000 and 8,000 tons per year. The train guard was expected to do the shunting at unstaffed stations.

Fruit, vegetables and flowers were important in season, the traffic concentrating at Staple where there was a wholesale greengrocers'. These were carried in boxes and baskets in open wagons, the empties being returned. Some potatoes, grain and hops were carried in sacks.

The Hammill brickworks shipped some bricks, but their product was of high quality and vulnerable to the jolting it might endure on the railway. Just under 4,000 tons were carried in 1930, but output after that tended to go by road.

Wingham Engineering received their supplies of steel plate, bar etc. by rail.

There was almost no livestock traffic, since the area has no tradition of stockbreeding. Twenty-two cattle were carried in the EKLR's lifetime. 336 pigs were carried in 1935, and 353 in 1936, which indicates the establishment or liquidation (or both, in quick succession) of a pig farm. Some wool was carried, because sheep were used to keep the grass down in orchards.

The railway is known to have stabled wagons not in use on the "North Bank Spur" at Shepherdswell, also on the Guilford spur near the junction. The sidings at Richborough Port were also probably used.

After passenger services ceased on the Richborough Port branch, it was worked "on demand" to the facilities at Sandwich Road and Richborough Castle. The siding at Poison Cross amounted to Eastry's goods yard, so main line train engines ventured this far to handle vehicles if necessary (the short distance was a separate block section). Alarmingly, towards the end main line trains could be left waiting, even if they had passengers, for the engines to run as far as Richborough Castle and back if need be.

Passengers

[edit]Interest obviously focuses most on passenger traffic, but it was of secondary importance and towards the end was trivial (three passengers every four trains in 1947). The established timetable pattern was three trains each way daily to Wingham and another to Eastry, running on to Wingham on Saturdays. When miners' trains ended in 1929 there were four each way, terminating in the colliery yard (prior to 1927, some of these ran on to Eastry, in which case they stopped at "Tilmanstone Colliery Halt" at Elvington, which was a serious source of confusion). The basic service became two each way in 1931.

Mostly, except in the early years, there were no proper passenger trains but a passenger coach attached to a goods train (forming the so-called "mixed train"). Since the EKLR had no guard's vans until the 1940s, the passenger coaches performed this function (being independently braked). The obvious disadvantage was that shunting made the passenger timetable a work of fiction. One way of making up time was by not stopping at stations where no passengers were waiting. There is anecdotal evidence that sometimes train crews ignored prospective passengers anyway if no goods traffic was to be handled at that stop.

The service from Eastry to Sandwich Road involved one train each way on weekdays in 1926, two on Wednesdays and Saturdays 1927, and one only on Saturdays 1928.[40] Since the passenger coach doubled up as the brakevan, the published assertions that it was left at Sandwich Road (while the rest of the train went on) need confirmation (this statement may have been for official ears). It is likely that anybody actually wishing to go on to Richborough Port would be allowed to travel free "at own risk", although there is no actual evidence that anybody did.

The EKLR never ran passenger trains on Sundays, nor did it sell First Class tickets (even though some carriages had first-class accommodation).

Tickets

[edit]Despite the volume of traffic, the EKLR did not use paper tickets but proper Edmondson card ones, of different colours according to the destination. Return tickets had the two appropriate colours. Train guards had to carry these for issue, since only the two terminal stations held stocks.

Ticket arrangements for the Richborough Port branch service are unknown. There was a sixpenny (£0.025) catch-all ticket for dogs, bicycles, items of luggage and prams. Apparently the EKLR did not forward luggage. There was no through booking onto the main line; passenger travelling to places such as Dover had to buy another ticket at the SECR/SR station at Shepherdswell.

Other revenue activities

[edit]The famously frugal Colonel Stephens made a point of selling the hay resulting from the mowing of the railway's verges.

A row of three bungalows at Golgotha, above the tunnel, were built by the EKLR in 1933 and rented to employees. These have recently been demolished and redeveloped.[41] Some land purchased for the Deal extension was also rented out, notably a terrace called "Fairlight Cottages" at Sholden.

A Chevrolet lorry was purchased in 1933 for a collection and delivery service at Staple, especially for the fruit and vegetable farmers. This was apparently a success, but the service seems to have ceased in the early part of the Second World War. The Station Agent at Staple used his own lorry after that, but was sacked in 1947 for moonlighting; he had been driving produce to the London markets overnight instead of forwarding it to the railway at Staple.[42]

Advertising rights along the right of way were rented to "Partington's Kent Billposting Co" in 1934. As a result, the stations at Canterbury Wingham Road, Richboro Port and Sandwich Road received double-sided roadside billboards.[43]

Ancillary businesses

[edit]The EKLR attracted no shop or pub to any of its stations. In fact, there is no evidence of any retail activity at any of them, not even a newspaper stand. Only three businesses seem to have been set up in response to the presence of a railway, all at Staple. A coal merchant operated there (elsewhere they stayed in the villages), and a trug basket manufacturers briefly operated in a large corrugated iron shed next to the sidings before this was taken over by a wholesale greengrocers' (C.W. Darley Ltd).[44]

Permanent way and signalling

[edit]Right of way

[edit]This was usually sufficient for double track on the main line, including the bridge and tunnel, but earthworks were for single track. Hence the revenue from haymaking. The fencing was post and wire. Nobody seems to have noticed any gradient posts. Anti-trespasser notices were in enamel. This was the text:[45]

EAST KENT RAILWAY. PUBLIC NOTICE NOT TO TRESPASS. The East Kent Railways Order, 1911 (Section 87) provides that any person who shall trespass upon any of the lines of the Railway shall on conviction be liable to a penalty not exceeding Forty Shillings, and the provisions of the Railway Clauses Consolidation Act, 1845, with respect to the recovery of damages not specially provided for and of penalties and of the determination of any other matters referred to justices, shall apply.

Any person or persons damaging or removing any portion of the Company's property shall be vigorously prosecuted. BY ORDER. H.F. Stephens, Engineer and General Manager. Penalty for destroying or defacing this notice, Five Pounds.

Trackage

[edit]Initially, the rails used were flat-bottomed, 80 lb per yard (90 lb in areas where heavy wear was expected), spiked directly on to the sleepers of creosoted Baltic pine. Only the sharp curve at Shepherdswell had the rails bent to shape; elsewhere, short straight lengths were used on curves. Colonel Stephens obtained various job lots of rails from the salvage dump at Richborough Port, and these included 60 lb rails which were used for the Wingham extension and the Richborough Port branch. The ballast used was colliery waste and ash. There was a universal speed restriction of 25 mph. [46]

Bridges

[edit]These were steel girders on brick abutments, unless specified. On the main line, there was one over the road at Eastry. The Richborough Port branch had a low one over the Goshall Stream north of Sandwich Road station, and the famous high-level pair over the SECR and the river. The river bridge had no abutments, and wooden trestles. There was a wooden bridge over the bridlepath from Coldred church to Shepherdswell on the Guilford branch, and the road from Coldred church to the village went over the branch on a bridge. Finally, there was a bridge over Wigmore Lane on the Tilmanstone Colliery branch.

The free-draining soil of most of the EKLR's locality meant that there are few streams and hence few culverts. There is a brick-built example accessible west of Ash Town station, and another one on the private track north of Sandwich Road station, over the North Poulders Stream. East of Wingham Canterbury Road the railway crossed the Wingham Stream, and merely dropped a concrete pipe in the streambed and piled the embankment on top, which remains to this day.

Level crossings

[edit]These were ungated, with wooden cattle grids, except for the crossing at Sandwich Road station which had gates which protected only one side of the line.

These were the level crossing listed with speed restrictions and requiring the whistle:[47] "Shepherds Well" (on Eythorne Road, now part of the preserved line and gated). "Eythorne" (on Shooters Hill, by station. As above.) "Wigmore Lane". "Occupation Road" (back entrance to Beeches Farm, a bridleway). "Thornton Road" (by Knowlton station). "Eastry South Halt" (on Heronden Road). "Drainless Drove" (by Woodnesborough station, on Hammill Road.) "Ringleton" (on Fleming Road). "Poulton" (on Poulton Lane, a byway). "Durlock" (by Staple station). "Occupation" (on Brook Farm Lane, a byway.) "Danbridge" -sic (by Wingham Colliery station, double on Staple Road and Popsal Lane). "Session House" (on Goodnestone Road, Wingham). "Adisham Road" (by Wingham Town station). "Canterbury Road" (by station).

Richborough Port branch "Poison Cross" (double on Drainless Road and Foxborough Hill, the station in between.) "Woodnesborough Road" (at Roman Road station). "Ash Road" (at Sandwich Road station). "Ramsgate Road" (at Richborough Port).

The Guilford branch had a level crossing on Long Lane east of Golgotha, and the Richborough Castle spur had one on Richborough Castle Road, although there is no evidence that a train ever used it.

Locomotive turning facilities

[edit]There were neither turntables or triangles anywhere on the EKLR, so engines ran tender first for much the time.

Signalling

[edit]The EKLR had no signalboxes or signalmen (although the ground frame at Eastry was in a shed until it fell down). Initially, there were ground frames controlling semaphores at Shepherdswell and Eythorne, but another one was installed at Eastry in 1925.[48] Elsewhere, signals controlling sidings were controlled by keys which simultaneously locked or unlocked the point levers. Thus there was no point rodding.

There were five block sections. The three on the main line, Shepherdswell-Eythorne, Eythorne-Eastry and Eastry-Wingham, were controlled by electric tablet, the first by Tyler's system and the other two by Webb & Thomson's. The Richborough branch had two sections, Eastry-Poison Cross and Poison Cross-Richborough Port, controlled by simple tablets kept in two boxes at Poison Cross (one with the notorious label "Poison Sandwich"). The junction spur had no signals, and was shunted over as an exchange siding.

There seem to have been no signals on the Richborough Port branch beyond Poison Cross. The junctions and crossings with the harbour sidings at the port seems to have been completely unprotected, except that photographs of the putative passenger station there show that the crossing over the harbour line immediately to the east, on the west verge of the road, was provided with a gate which was presumably opened and closed by the train crews.

At nationalisation, the electric tablet systems were out of order and the block sections were operated as "one engine in steam". The semaphores north of Eythorne were reported as derelict.

Staff

[edit]- The Directors were based at the company's registered office at Moorgate in London, and met once a year.

- The General Manager, Colonel Stephens and then W.H. Austen, was based at Tonbridge. Visits to the EKLR had to fit in with their responsibilities for their other light railways. There was an alarming lack (to modern eyes) of on-site management at the EKLR. Supervision depended on unannounced visits by the General Manager.

- At nationalisation, there were 34 posts, of which one was vacant and one not being filled:[49]

- Clerk and assistant in the scout-hut office, responsible for the paperwork and for Shepherdswell station.

- Three sets of train crew, being driver, fireman and guard (one fireman's post was not being filled). The drivers did not work off the EKLR. The guard occupied the brake compartment in the passenger carriage, did the shunting at unstaffed stations and sold tickets. The published assertion that he had to clamber along the outside of the carriage in order to sell tickets while the train was moving is unbelievable, and needs confirmation.

- A fitter and mate, a carpenter and a cleaner at the engine shed. The importance of the fitter in keeping the locomotives going was demonstrated by his being the highest-paid employee, receiving more than the clerks and drivers.

- For track maintenance, three gangers and ten linesmen.

- "Station Agents" (EKLR term for stationmaster) at Staple and Wingham Canterbury Road.

- Porters at Eastry, Staple and Eythorne.

- There was a uniform, with "EKR" on the cap.[50]

- The platelayers had an old van bodies as a hut at Eastry, two small huts by Wingham Engineering works and another by the old Guilford junction at Eythorne.

- Colonel Stephens would sack on the spot any man he discovered belonging to a union, but Austen allowed individuals to join the National Union of Railwaymen. There was no union branch at the EKLR, however; these men seem to have belonged to the Dover branch of the NUR.

- Pay was below industry standard, and there was no pension scheme. Working conditions could be bad; for example, the engine crews had to work half-cab locomotives tender-first half the time. There was no canteen or washing facilities, and conditions in the workshops at Shepherdswell were very primitive.[51] Nobody seems to have noted any staff toilet there. However, narrative evidence suggests that there was a lot of spare time on the job, although tales of staff drinking beer in pubs while their trains waited (which would entail instant dismissal on the main line) are probably urban legends. It seems that the staff used the pubs near the railway at Shepherdswell, Eythorne, Woodnesborough and Port Richborough as places to wait over and to have their lunches in the absence of any company facilities (tragically, of these only one of the two station pubs at Shepherdswell survives).

Remnants

[edit]The EKLR is one of the best examples of how a railway can dissolve back into the countryside after abandonment, leaving only a few isolated landscape features.[52]

Track removal north of the northern junction of the Tilmanstone Colliery loop occurred in May 1954, and most of the trackbed has since been ploughed out. (Sometimes this left a surviving boundary.) The main line between this point and the southern junction, through Elvington Halt, was apparently kept on for a while as part of the internal colliery rail system. The final section of line to Shepherdswell was abandoned after the closure of Tilmanstone colliery in 1986.[30][53]

Unless specified, all surviving trackbed is occupied by shrubs (some very thorny) and mature trees.

Main line:

- Shepherdswell. Earthworks of the abortive junction spur are in the self-sown wood ("The Knees") north of the stations.

- Eythorne Station to Beeches Farm bridle path. 1,800 metres (2,000 yd). Trackbed could be traced from Eythorne through Elvington and along the west side of the colliery waste tip until recently. Part of this was obliterated by tip landscaping in 2007. It continues on the other side of the bridle path as a fence boundary, 230 metres (250 yd). Between the site of Wigmore Lane crossing and just south of Elvington the embankment is mostly intact and walkable, with several rotten sleepers abandoned in situ. One still has a spike for a flat-bottomed rail in it.

- Elvington Halt. The overgrown platform face survives, of red stock bricks with edging in blue engineers'. Some sawn-off lengths of original EKLR bullhead rail are used as a vehicle barrier at the start of the access path in Elvington; the original rail used was flat-bottomed so these seem to belong to a re-laying of the line from Shepherdswell to the colliery from 1939.[29]

- Knowlton Station, trackbed to south, 250 metres (270 yd).

- Black Lane Crossing (west of Thornton Lane south of Eastry). Low embankment either side of crossing, 630 metres (690 yd). Black Lane is an old bridleway from Canterbury to Deal.

- South Eastry Station, trackbed narrowed by ploughing to south, 800 metres (870 yd); fence boundary of new housing estate to north, 200 metres (220 yd).

- Eastry Station. Trackbed to south, 380 metres (420 yd). Embankment to north, including junction, 400 metres (440 yd). to reservoir then hedge boundary, 250 metres (270 yd).

- Woodnesborough Station. Hedge boundary to southeast, 200 metres (220 yd) (useful in pinpointing location of station).

- Ringlemere Farm. A private farm track using the trackbed runs the northwest of the pumping station to Ash parish boundary, 1,000 metres (1,100 yd). Can be examined via a public footpath from Black Pond Farm to Coombe.

- Ash Town Station. Hedge boundary to east, 100 metres (110 yd). A public footpath follows the landscaped trackbed to Poulton Farm driveway. A culvert survives on this. The area is part of the Jack Foat Trust country park.

- Staple Station. Fence boundary to west, 300 metres (330 yd), then rough grass trackbed 500 metres (550 yd) before footpath to Staple. This was not ploughed up because it is on the wrong side of a farm boundary.

- Wingham Colliery Station. Field boundary to the northeast, 250 metres (270 yd).

- Wingham. Two embankments survive from Wingham Colliery to Canterbury Road. The easternmost has been partly removed and grassed, and can be viewed from the road west of Dambridge Farm. It was built of colliery waste, and caught fire and burned from 1938 to 1945.[54] A summer-house marks it. 2,500 metres (2,700 yd). Fence boundaries continue the route to the cemetery, 400 metres (440 yd), and at the school 100 metres (110 yd). The westernmost embankment is well preserved, and is best viewed from a footpath from Wingham Bridge to Wingham Well. It was obviously made using waste from Tilmanstone Colliery. 100 metres (110 yd), then 100 metres (110 yd) boundary to road. There is a notice for the "Wingham Station Farm Shop" opposite the site of the Canterbury Road station. (2009: The shop name has been changed to the "Little Stour Farm Shop".)

Richborough Port branch:

- Eastry Junction to Drove Farm. Embankment 400 metres (440 yd). Continues as fence boundaries the other side of Poison Cross, 850 metres (930 yd).

- Roman Road. Embankment to north, which can be seen from the Sandwich bypass north of the Woodnesborough Road bridge. 230 metres (250 yd).

- Great Poulders Farm. Trackbed adjacent to, and east of, the bypass, north of bridge. 250 metres (270 yd).

- Sandwich Road. Trackbed as private farm track north of roundabout, 500 metres (550 yd).

- Stour River Bridges. Embankments either side, reaching to bypass. 520 metres (570 yd). Four brick piers survive close to Richborough Castle, for the spans over the SECR railway and the adjacent road, with the embankment retaining wall lacking its embankment (partly removed for agriculture). There was a short embankment between this bridge and the river bridge proper, which was built of girders on timber trestles and which has left no trace.

- Monks Way Roundabout. A curved line of shrubs to the south marks the trackbed. 350 metres (380 yd).

Any surviving remnants at Richborough Port have vanished in the recent massive developments there.

The parish boundary between Sandwich and Woodnesborough follows part of the route of the Richborough Port line.

Spurs:

- Tilmanstone Colliery. The preserved railway runs to the former Wigmore Lane bridge, where one brick abutment survives. 100 metres (110 yd) of trackbed survives the other side of the road; the rest has been obliterated by the industrial estate.

- Woodnesborough Colliery. The field due south of the mushroom farm has a curved hedge marking part of the route.

- Wingham Colliery. Obliterated. Apparently one building survives with rails in its floor.

- Wingham Engineering. The present company, "Intake Engineering", states that there are rails in the floor of its factory.[55]

- Guilford Colliery. 100 metres (110 yd) from junction, to the southwest (footpath access from Eythorne Court; the trackbed can be walked). Trackbed to Long Lane, 700 metres (770 yd). Trackbed in a semicircle around Coldred church, embankment crossing over South Downs Way (the bridge was wooden, so no remains), then a cutting with a bridge carrying the Coldred Church road (west side filled in, bridge gone). 800 metres (870 yd).

- Richborough Castle Siding. The overgrown route is traceable; part is now a wood.

A ghost of the proposed Deal line survived as a property boundary on the west side of Sandwich Road in Eythorne, at "The Outback", but has been lost through development.[56] A shallow cutting was started in Willow Wood; a belt of scrub along the southern edge of this otherwise flower-rich ancient wood is the only evidence left for the scheme.

Preservation

[edit]A historic railway preservation society operates trains between Shepherdswell and Eythorne.

Locomotives

[edit]The East Kent Light Railway had a total of ten locomotives.[30]

- No.1. 0-6-0ST built 1875 by Fox, Walker & Co. (Works No. 271) for the Whitland and Cardigan Railway. To Great Western Railway in 1886, then Bute Works Supply Co., and EKLR in 1911. Working until the early 1930s, last known in steam on 22 September 1934, scrapped by September 1935.[57]

- No.2. Walton Park 0-6-0ST built 1908 by Hudswell Clarke (Works No. 823) for the Weston, Clevedon & Portishead Railway. Worked on the Shropshire & Montgomeryshire Railway before transfer to EKLR in 1913. Loaned to the PD&SWJR in 1917. Last known in traffic on 23 August 1943. Sold for scrap in 1943, but later worked at Purfleet Deep Water Wharf and Hastings Gas Works, scrapped in July 1957.[57]

- No.3. 0-6-0, built December 1880 by Beyer, Peacock and Company (Works No. 2042), ex LSWR 282 class No. 0394. Purchased in November 1918, boiler condemned 1930, sold for scrap on 24 April 1934.[57][58]

- No.4. 0-6-0T, built 1917 by Kerr, Stuart and Company ("Victory" Class, Works No. 3067) for Inland Waterways Docks Dept. of the Royal Engineers No.11 and ROD No. 610. Purchased 1919 as replacement for Gabrielle. To British Railways (Southern Region) in 1948, renumbered 30948;[59] scrapped 1949.[58][60]

- No.5. 4-4-2T built March 1885 by Neilson and Company (works no. 3209), ex LSWR 0415 Class no. 488, renumbered 0488 in March 1914 and sold to the Ministry of Munitions September 1917, for use at Ridham Salvage Depot, Sittingbourne, Kent.[61] Purchased by EKLR in April 1919 for £900 and numbered 5. Repaired 1937, and laid aside at Shepherdswell in March 1939. Sold to the Southern Railway in March 1946 for £800, overhauled, numbered 3488 and returned to service 13 August 1946 for use on the Lyme Regis branch. To British Railways 1948 and renumbered 30583 in October 1949. Withdrawn and sold to the Bluebell Railway for preservation in July 1961.[60][62]

- No.6. 0-6-0 built August 1891 by Sharp, Stewart and Company (works no. 3714), ex SECR O class no. 372. Purchased from Southern Railway May 1923, received June 1923 and numbered 6. Rebuilt to O1 class specification in October 1932. To British Railways 1948, allocated no. 31372 (not renumbered). Withdrawn 12 February 1949, scrapped 26 February 1949.[63][64]

- No.7. 0-6-0ST built 1882 by Beyer, Peacock and Company. Ex LSWR and War Office. Purchased 1926, Last in traffic 28 September 1944. Sold to the Southern Railway in 1946. Scrapped at Ashford Works 23 March 1946.[60]

- No.8. 0-6-0 built September 1891 by Sharp, Stewart and Company (works no. 3718), ex SECR O class no. 376 and Southern Railway no. A376. Purchased September 1928 and numbered 8. Withdrawn March 1935 and cannibalised for spares.[63][64]

- No.100. 0-6-0 built September 1893 by Sharp, Stewart and Company (works no. 3950), ex SECR O class no. 383, Southern Railway A383 then 1383. Rebuilt to O1 class specification in December 1908. Purchased 29 May 1935 to replace no.8, received 23 June 1935 and numbered 100; renumbered 2 in July 1946. To British Railways in 1948, renumbered 31383 in October 1949. Withdrawn 7 April 1951, scrapped 21 April 1951.[63][64]

- No. 1371. 0-6-0 built August 1891 by Sharp, Stewart and Company (works no. 3713), ex SECR O Class no. 371, Southern Railway A371 then 1371. Rebuilt to O1 class specification in May 1909. Purchased February 1944 to replace no. 5, received March 1944 (not given EKR number). To British Railways in 1948, allotted no. 31371 (not renumbered). Withdrawn 8 January 1949, scrapped 19 February 1949 still carrying former SR number 1371.[63][65]

- The Hawthorn, Leslie Twins Two 0-6-0T's were built in 1913 by Hawthorn, Leslie, having been ordered for the EKLR by its contractor. One was called "Rowenna" and the other "Gabrielle" after two granddaughters of Arthur Burr, the coalfield promoter. There was no money to pay for them, so they were sold on before delivery. The former ended up in the Fife, Scotland coalfield while the latter saw War Office service before working in steelworks at Ebbw Vale and Scunthorpe.[66]

- Hired from the Kent & East Sussex Railway.[67]

- KESR No.2 "Northiam". 2-4-0 sidetank, built by Hawthorn, Leslie in 1899. It was used on construction work on the EKLR from 1912 to 1914, and returned in 1921. It probably remained with the EKLR until 1930 (records are lacking). It was scrapped at Rolvenden in 1941.

- KESR No. 4 "Hecate". 0-8-0 sidetank built by the same company (works no. 2587) in 1904. This is the engine traditionally regarded as having been purchased by the KESR for working its abortive extension to Maidstone, but little used by that railway because of its weight. It was hired to the EKLR from 1916 to 1921 (but not used after October 1919 due to a need for repairs), where it was used on construction trains for the extension to Eastry to Sandwich Road and for the Tilmanstone Colliery marshalling yard. In later years it was sold to the Southern Railway in July 1932 and numbered 949; it passed to British Railways at Nationalisation, was allotted number 30949 (but not renumbered), and following a collision at Nine Elms was withdrawn on 20 March 1950, being scrapped at Eastleigh by the end of the month.[68]

- War Department Engines.[69]

Only one class of these is known to have operated on the EKLR during the Second World War for the rail-mounted guns based there, being the Great Western Railway 0-6-0 "Dean Goods". It is known that some of them had condensing gear, which would have put them well over the safety limit for the track to Staple and helps explain the compensation payments for track damage to the EKLR by the War Office.

- Locomotives Hired from the Southern Railway.[70]

There is one mysterious reference in 1931 to the Southern Railway being paid for the loan of a locomotive.

During the Second World War, the following O1 locomotives were hired: 1426, up to 24 September 1942 (duration of hire unknown). 1430, 19 April to 7 December 1943. 1066, 20 December 1943 to 7 March 1944. 1437, 7 March 1944 to 27 March 1944. 1373, 23 March 1945 to 23 May 1945, again 3 December 1945 to 11 February 1945.

Also a T-class 0-6-0T, 1604, 28 September 1944 to 13 January 1945.

- Livery

There was no one livery for engines and carriages under Colonel Stephens, but under Austen a livery of Southern Railway mid-green with yellow lettering was being introduced as and when repainting was required.

Chapter 15 of Lawson Finch's book includes pictures and descriptions of liveries sufficient for modelling purposes.

- There was an urban legend that a contractor's engine derailed and bogged down during the building of the abortive junction spur at Shepherdswell, only to be buried in the embankment. The "Abandoned Locomotive" legend is popular worldwide, especially in the USA.[71]

- Colonel Stephens tried to do repairs and refits "in-house" despite the primitive facilities, but major repairs were done at the Southern Railway's Ashford locomotive works and more advantage was taken of this facility under Austen.

Carriages, wagons etc.

[edit]The East Kent Light Railway had a total of 14 carriages during its history.

- Unknown number 4 wheel, 4 compartment, Third.

- Built March 1876 by Brown Marshall, ex GER No. 279 and KESR No. 13. To EKLR 1912, destroyed in accident at Shepherdswell in 1917 or 1919 (sources vary)[30][72]

- 1 bogie Open Brake Composite Corridor.

- Built 1905, ex KESR No. 17. To EKLR c.1912, withdrawn 1948.[72]

- 2 4 wheel Brake

- 3 4 wheel, 4 compartment Composite.

- Built c.1873, ex CLC and KESR No. 12. To EKLR c.1912, withdrawn 1946. Body to Staple for use as a bungalow.[72]

- 4 6 wheel, 4 compartment Brake Composite.

- 5 6 wheel, 3 compartment Brake Composite.

- 5 bogie 5 compartment Brake Corridor,.

- Built July 1911. ex LSWR, SR no. 3126. To EKLR February 1946, withdrawn 1948. Body used as an office at Worthing goods yard from September 1948.[72][73]

- 6 4 wheel, 5 compartment Third.

- Built c.1873, ex CLC and KESR No.11. To EKLR c.1912, withdrawn 1936. Body grounded at Staple station in 1937 and used as an office.[72][73]

- 6 bogie 5 compartment Brake Corridor.

- Built July 1911. ex LSWR, SR no. 3128. To EKLR February 1946, withdrawn 1948.[72]

- 7 4 wheel, 4 compartment Third (ex First)

- 8 4 wheel, 4 compartment Third.

- Built 1886, ex LCDR and SECR No. 2737. To EKLR 1921, withdrawn 1947.[72]

- 9 4 wheel, 3 compartment Brake Third

- Built 1880, ex LCDR and SECR No. 3268. To EKLR 1940, withdrawn 1947.[72]

- 10 6 wheel, 3 compartment Brake Composite.

- Built 1893, ex LCDR and SECR No. 2663. To EKLR 1926, withdrawn 1948.[72]

- 11 6 wheel, 3 compartment Brake Composite.

- Built 1891, Ex LCDR, SECR and SR No.2691. To EKLR 1927, withdrawn 1948.[72]

Goods Vehicles:-

- Open Wagons.[74]

These were basically wooden boxes on four wheels, some with drop sides, and were used to carry everything from cut flowers in baskets to coal. Tracing of individuals is impossible, but apart from four new ones at the start of operations they were all second-hand. Numbers started at 15, reached a maximum of 35 in the 1930s, then 29 during the Second World War.

Tilmanstone Colliery had its own fleet of motley and disgraceful coal wagons (one job at the colliery was to check that returning empties still had floors).[75] There is a strong rumour that several of these were buried in the waste tip.[76]

- Box cars

For the carriage of parcels. The EKLR had two for most of its life.

- Timber trucks

These were basically bogie wagons with metal bar restraints. There were three, reputedly from the Highland Railway.

- Brake vans

The EKLR did not use these for most of its life, which meant that all trains depended on the engine and passenger coach (if one attached) for brakes. However, it purchased three after 1942.

- Maintenance vehicles

There was a little ten-ton breakdown crane, and several (at least four) hand-operated pump trucks for the permanent way staff to use. Two were noted at Eastry, and two at Wingham. Miller trucks (the L-shaped things with two wheels) were noted at Eastry and Staple.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Keys to Canterbury". Stephens Museum. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Butler 1999, pp. 2ff.

- ^ "East Kent Mineral Railways". Dover Express. 27 May 1910. p. 5.

- ^ "East Kent Mineral Railways". Canterbury Journal, Kentish Times and Farmers' Gazette. 22 October 1910. p. 7.

- ^ "Kent Coal Progress". Dover Express. 4 August 1911. p. 6.

- ^ "East Kent Light Railway". Folkestone Express, Sandgate, Shorncliffe & Hythe Advertiser. 19 June 1912. p. 4.

- ^ "Kent Coal Concessions Ltd". Kentish Express. 12 October 1912. p. 9.

- ^ "East Kent Light Railways - First General Meeting". Dover Chronicle. 30 November 1912. pp. 7–8.

- ^ "East Kent Light Railway". Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald. 17 May 1913. p. 7.

- ^ "The East Kent Light Railway". Kentish Express. 3 January 1925. p. 5.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 137.

- ^ "East Kent Railway". Dover Chronicle. 28 March 1925. p. 2.

- ^ "A Light Railway's War". The Colonel Stephens Society. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Dismantling the East Kent". The Colonel Stephens Society. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Butler 1999.

- ^ For example, the map at Butler (1999) p33 contradicts the text.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 57.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, pp. 131ff.

- ^ Course 1976, p. 104.

- ^ a b BR 1948 diagram.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 447.

- ^ Course 1976, p. 72.

- ^ Course 1976, p. 75.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, pp. 253ff.

- ^ a b Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 273.

- ^ Archaeology Data Service.[full citation needed]

- ^ Eastry RDC highways report book No.2 district, Kent County Archives, RD/Ea/H10.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 293.

- ^ a b Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 459.

- ^ a b c d The East Kent Light Railway[full citation needed]

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 132.

- ^ a b Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 152.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 300.

- ^ Course 1976, p. 76.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 70.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Beddall 1997, p. 32.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 81.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, pp. 447ff.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett2003, p. 315.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 173.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, pp. 173, 207, 223.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Smith & Mitchell 1989, pic 106.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 185.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 487.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 458.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 455.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 229.

- ^ Smith & Mitchell 1989, pic 80.

- ^ Smith & Mitchell 1989, pic 32.

- ^ Google Earth 2008 and OS Explorer sheets 138 and 150.

- ^ Glasspool, David. "Shepherds Well". Kent Rail.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 305.

- ^ Company website.[full citation needed]

- ^ OS "Explorer", sheet 138, 1997, TR286498.

- ^ a b c "Locomotives of the East Kent Railway, Part 1: Early Years". Stephens Museum. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Minor Railways & Tramways Locomotives". Archived from the original on 23 July 2018.

- ^ British Railways Locomotives 1948-50. Vol. Part 2—10000-39999. Shepperton: Ian Allan. 1973 [1949]. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7110-0401-6.

- ^ a b c "Locomotives of the East Kent Railway, Part 2: More Odds and Ends". Stephens Museum. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Neale, Andrew (2 October 2008). "Must we let this be swept away?". Heritage Railway. Issue. 116: 42–46.

- ^ Bradley 1967, pp. 23, 25–27.

- ^ a b c d Bradley 1985, pp. 153, 159.

- ^ a b c "Locomotives of the East Kent Railway, Part 3: East Kent Standards". Stephens Museum. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 396.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 398.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 401.

- ^ Bradley 1975, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 407.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 406.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "East Kent Railway Carriages". Stephens Museum. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007.

- ^ a b "East Kent Railway Carriages". Stephens Museum. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, pp. 433ff.

- ^ Smith & Mitchell 1989, pic 72.

- ^ Lawson Finch & Garrett 2003, p. 445.

Sources

[edit]- Beddall, Matthew (1997). East Kent Light Railway, A History of the Line in Combination with the Kent Coalfield. Solo Publications. ISBN 978-0-9532952-0-3.

- Bradley, D.L. (1967). Locomotives of the L.S.W.R. Vol. Part 2. Railway Correspondence and Travel Society.

- Bradley, D.L. (October 1975). Locomotives of the Southern Railway. Vol. Part 1. London: Railway Correspondence and Travel Society. ISBN 978-0-901115-30-0.

- Bradley, D.L. (September 1985) [1963]. The Locomotive History of the South Eastern Railway (2nd ed.). London: Railway Correspondence and Travel Society. ISBN 978-0-901115-48-5.

- Butler, Robert (1999). Richborough Port. Ramsgate Maritime Museum. ISBN 978-0-9531801-1-0.

- Catt, A.R. (1970). East Kent Light Railway. Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-017-5.

- Course, Edwin (1976). The Railways of Southern England: Independent & Light Railways. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-3196-4.

- Elks, Ken (2002). East Kent Railway Tickets, 1916-48. Solo Publications. ISBN 978-0-9532952-2-7.

- Lawson Finch, Maurice; Garrett, Stephen R. (2003). East Kent Railway (two vv). Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-609-2.

- Harding, Peter (1997). Memories of the East Kent Light Railway. self published. ISBN 978-0-9523458-2-4.

- Klapper, Charles (1937). East Kent Light Railway. Railway Magazine. This is a rare item. Dover Library has a reference copy.

- Ritchie, Arthur Edward (1919). Kent Coalfield, Its Evolution and Development. Iron and Coal Trades Review. ISBN 9785877742871.

- Smith, Keith; Mitchell, Vic (1989). The East Kent Light Railway. Midhurst, Sussex, UK: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-61-1.

- The best map showing the EKLR at its height is the Ordnance Survey One-Inch, 1926 revision.

- For details, Ordnance Survey Twenty-Five Inch, 1937 revision. (These maps were left unfinished at the start of WWII, and some EKLR tracks were left undrawn.)

- British Railways 1948 track diagrams.

- Google Earth shows a surprising amount of the route surviving as crop marks.

Further reading

[edit]- Carpenter, Roger (Winter 1988). Karau, Paul; Beale, Gerry (eds.). "The Wingham Extension of the East Kent Railway". British Railway Journal (20). Didcot: Wild Swan Publications Ltd. ISSN 0265-4105.

- Scott-Morgan, John (1978). The Colonel Stephens Railways: A Pictorial Survey. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7544-X.