| Battle at the End of Time | |

|---|---|

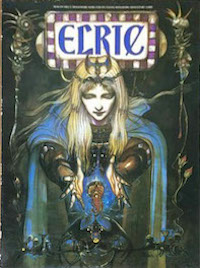

Cover by Steve Leialoha and Steve Oliff | |

| Other names | Elric |

| Designers | |

| Illustrators | |

| Publishers | Chaosium |

| Publication | 1982 |

| Genres | Fantasy board wargame |

Elric: Battle at the End of Time is a board wargame published by Chaosium in 1982, an update of the 1977 game simply titled Elric.[1] It is based on the Elric of Melniboné books by Michael Moorcock. There have been three English language editions, Elric (1977), Elric: Battle at the End of Time (1982), and Elric (1984), published by Avalon Hill.

Gameplay

[edit]Elric is a game about Elric of Melniboné, the central protagonist in a series of novels by Michael Moorcock. In each scenario of the game, players are assigned primary personalities from the novels, and the players then draw cards which allow the players to "muster" additional personalities and armies.[2]

Publication history

[edit]The original 1977 edition came packaged in a ziplock bag with a rule book, a paper map and counters.[1] In 1982, the rules were updated and revised, and the production values upgraded. The game now came packaged in a box, and included a 12-page rules folio, a 22" x 34" map, and 320 die-cut double-sided counters. The price was increased from $12 to $20.[1] In 1984, Avalon Hill published an edition of the game based on the 1982 edition, with updated box art. Hobby Japan released a Japanese language version based on the 1984 edition.[3]

Reception

[edit]In the November–December 1977 edition of The Space Gamer (Issue No. 14), Neil Shapiro liked the game, saying, "Elric is more than a game. It is a very accurate, emotional representation of one of Fantasy literature's greatest sagas. It is a myth made real and brought to the gameboard. As an examination of one Cycle of Moorcock's Eternal Champion, it is unique. As a game, it has few equals."[2]

In The Playboy Winner's Guide to Board Games, game designer Jon Freeman noted that "The rules to Elric are a mess — full of grammatical and typographical atrocities, misspellings, nonwords, and confusing nonsentences." Freeman also thought luck played too great a factor, commenting "the random, Cheshire Cat behavior of Elric minimizes any exercise of skill and helps limit the audience [...] to people hopelessly addicted to Moorcock's brand of sword-and-sorcery."[4]

Gary Porter reviewed Elric for White Dwarf #6, giving it an overall rating of 7 out of 10, and stated that "Elric is a credit to its designer, publisher and original begetter. The lack of hexes on the map and the movement and replacement rules are very reminiscent of Russian Civil War - no bad thing. The original features: the magic cards, the battalia, the cosmic balance, etc., make this a fantasy game apart."[5]

Several years later, Patrick Amory re-reviewed Elric in the October 1980 edition of The Space Gamer (Issue No. 32), and judged that the game had held up over the past three years: "the first scenario is smooth-playing, pleasantly unpredictable, and entertaining. As it simulates very accurately the chaos and adventure of Elric's world, the game will appeal to Moorock fans."[6]

Murray Writtle reviewed Elric for White Dwarf #33, giving it an overall rating of 7 out of 10, and stated that "All in all an enjoyable game, recreating the books quite successfully, though a little slow to play and subject to a fair degree of chance."[7]

In the December 1982 edition of Dragon (Issue #68), Tony Watson reviewed the revised edition, and although he liked the new components, he found for a game of strategic army combat to be too simple, and questioned the replay value: "The rules for conducting these campaigns are simplistic and uninteresting... I found the play of the game to be a bit meandering and lacking direction. This is not a game that seems to have much replay value... If atmosphere were all that mattered, Chaosium would have a winner, but as it stands, Elric is basically a game that’s all dressed up with nowhere to go, recommended for die-hard Elric fans only."[1]

In a retrospective review of the 1984 version of Elric in Black Gate, John ONeill said "Avalon Hill made a good show of it, replacing Chaosium's notoriously flimsy components — especially their paper maps and thin counters — with their own hard-stock folding maps and firm counters. The rather dense rules, however [...] survived."[8]

- Game editions

-

Elric, 1977 edition

cover by Steve Leialoha -

Elric, 1984 edition

cover by Kenn Nishiuye -

Elric, Hobby Japan edition

cover by Yoshitaka Amano

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Watson, Tony (December 1982). "New edition of Elric is best left to die-hard fans". Dragon (68). TSR, Inc.: 79–80.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Neil (November–December 1977). "Reviews". The Space Gamer (14). Metagaming: 39–40.

- ^ "Elric". BoardgameGeek. BoardgameGeek LLC. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Freeman, Jon (1979). The Playboy Winner's Guide to Board Games. Chicago: Playboy Press. p. 252. ISBN 0872165620.

- ^ Porter, Gary (April–May 1978). "Open Box". White Dwarf (6). Games Workshop: 12–13.

- ^ Amory, Patrick (October 1980). "Capsule Reviews". The Space Gamer (32). Steve Jackson Games: 25.

- ^ Writtle, Murray (September 1982). "Open Box". White Dwarf (33). Games Workshop: 13.

- ^ "Vintage Treasures: Avalon Hill's Elric Young Kingdoms Adventure Game – Black Gate". 22 July 2013.