Eagle and palette design regarded as the logo of the Federal Art Project | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 29 August 1935 |

| Dissolved | 1943 |

| Jurisdiction | United States |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Agency executive | |

| Parent department | Works Progress Administration (WPA) |

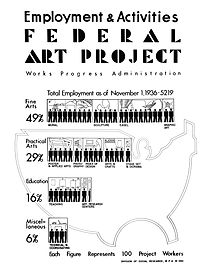

The Federal Art Project (1935–1943) was a New Deal program to fund the visual arts in the United States. Under national director Holger Cahill, it was one of five Federal Project Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the largest of the New Deal art projects. It was created not as a cultural activity, but as a relief measure to employ artists and artisans to create murals, easel paintings, sculpture, graphic art, posters, photography, theatre scenic design, and arts and crafts. The WPA Federal Art Project established more than 100 community art centers throughout the country, researched and documented American design, commissioned a significant body of public art without restriction to content or subject matter, and sustained some 10,000 artists and craft workers during the Great Depression. According to American Heritage, “Something like 400,000 easel paintings, murals, prints, posters, and renderings were produced by WPA artists during the eight years of the project’s existence, virtually free of government pressure to control subject matter, interpretation, or style.”[1]

Background

[edit]The Federal Art Project was the visual arts arm of Federal Project Number One, a program of the Works Progress Administration, which was intended to provide employment for struggling artists during the Great Depression. Funded under the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, it operated from August 29, 1935, until June 30, 1943. It was created as a relief measure to employ artists and artisans to create murals, easel paintings, sculpture, graphic art, posters, photographs, Index of American Design documentation, museum and theatre scenic design, and arts and crafts. The Federal Art Project operated community art centers throughout the country where craft workers and artists worked, exhibited, and educated others.[3] The project created more than 200,000 separate works, some of them remaining among the most significant pieces of public art in the country.[4]

The Federal Art Project's primary goals were to employ out-of-work artists and to provide art for nonfederal municipal buildings and public spaces. Artists were paid $23.60 a week; tax-supported institutions such as schools, hospitals, and public buildings paid only for materials.[5] The work was divided into art production, art instruction, and art research. The primary output of the art-research group was the Index of American Design, a mammoth and comprehensive study of American material culture.

As many as 10,000 artists were commissioned to produce work for the WPA Federal Art Project,[6] the largest of the New Deal art projects. Three comparable but distinctly separate New Deal art projects were administered by the United States Department of the Treasury: the Public Works of Art Project (1933–1934), the Section of Painting and Sculpture (1934–1943), and the Treasury Relief Art Project (1935–1938).[7]

The WPA program made no distinction between representational and nonrepresentational art. Abstraction had not yet gained favor in the 1930s and 1940s, so was virtually unsalable. As a result, the Federal Art Project supported such iconic artists as Jackson Pollock before their work could earn them income.[8]

One particular success was the Milwaukee Handicraft Project, which started in 1935 as an experiment that employed 900 people who were classified as unemployable due to their age or disability.[2]: 164 The project came to employ about 5,000 unskilled workers, many of them women and the long-term unemployed. Historian John Gurda observed that the city's unemployment hovered at 40% in 1933. "In that year," he said, "53 percent of Milwaukee's property taxes went unpaid because people just could not afford to make the tax payments."[9] Workers were taught bookbinding, block printing, and design, which they used to create handmade art books and children's books. They produced toys, dolls,[10] theatre costumes, quilts,[9] rugs, draperies, wall hangings, and furniture that were purchased by schools, hospitals,[2]: 164 and municipal organizations[11] for the cost of materials only.[12] In 2014, when the Museum of Wisconsin Art mounted an exhibition of items created by the Milwaukee Handicraft Project, furniture from it was still being used at the Milwaukee Public Library.[9]

Holger Cahill was national director of the Federal Art Project. Other administrators included Audrey McMahon, director of the New York Region (New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia); Clement B. Haupers, director for Minnesota;[13] George Godfrey Thorp (Illinois),[14] and Robert Bruce Inverarity, director for Washington. Regional New York supervisors of the Federal Art Project have included sculptor William Ehrich (1897–1960) of the Buffalo Unit (1938–1939), project director of the Buffalo Zoo expansion.[15]

Notable artists

[edit]Some 10,000 artists were commissioned to work for the Federal Art Project.[6] Notable artists include the following:

- William Abbenseth[16]

- Berenice Abbott[17]

- Ida York Abelman[2]: 178

- Gertrude Abercrombie[18]

- Benjamin Abramowitz[19]

- Abe Ajay[20]

- Ivan Albright[2]: 161

- Maxine Albro[21]

- Charles Alston[22]

- Harold Ambellan[23]

- Luis Arenal[24]

- Bruce Ariss[25]

- Victor Arnautoff[26]

- Sheva Ausubel[27]

- Jozef Bakos[28]

- Henry Bannarn[29]

- Belle Baranceanu[30]

- Patrociño Barela[31]

- Will Barnet[32]

- Richmond Barthé[33]

- Herbert Bayer[2]: 195

- William Baziotes[34]

- Lester Beall[2]: 194

- Harrison Begay[35]

- Daisy Maud Bellis[36][37]

- Rainey Bennett[38]: 138

- Aaron Berkman[39]

- Leon Bibel[40]

- Robert Blackburn[2]: 170

- Arnold Blanch[38]: 153

- Lucile Blanch[41]

- Lucienne Bloch[5]

- Aaron Bohrod[38]: 144

- Ilya Bolotowsky[42][43]

- Adele Brandeis[44]

- Louise Brann[45]

- Edgar Britton[38]: 138

- Manuel Bromberg[46]

- James Brooks[47][48]

- Selma Burke[49]

- Letterio Calapai[50]

- Samuel Cashwan[38]: 156

- Giorgio Cavallon[51]

- Daniel Celentano[52]

- Dane Chanase[53]

- Fay Chong[54]

- Claude Clark[55]

- Max Arthur Cohn[56]

- Eldzier Cortor[57]

- Arthur Covey[58]

- Alfred D. Crimi[59]

- Francis Criss[60]

- Allan Crite[38]: 144

- Robert Cronbach[23]

- John Steuart Curry[58]

- Philip Campbell Curtis[61]

- James Daugherty[58]

- Stuart Davis[62]

- Adolf Dehn[63]

- Willem de Kooning[2]: 186

- Burgoyne Diller[64]

- Isami Doi[65]

- Mabel Dwight[2]: 180, 182

- Ruth Egri[66]

- Fritz Eichenberg[67]

- Jacob Elshin[54]

- George Pearse Ennis[68]

- Angna Enters[69]

- Philip Evergood[2]: 161, 174

- Louis Ferstadt[70]

- Alexander Finta[71]

- Joseph Fleck[35]

- Seymour Fogel[5][38]: 138

- Lily Furedi[72]

- George Michael Gaethke[73]

- Todros Geller[74]

- Aaron Gelman[58]

- Eugenie Gershoy[75]

- Enrico Glicenstein[76]

- Vincent Glinsky[77]

- Bertram Goodman[78]

- Arshile Gorky[2]: 186

- Harry Gottlieb[38]: 154

- Blanche Grambs[38]: 154

- Morris Graves[54]

- Balcomb Greene[43]

- Marion Greenwood[79]

- Waylande Gregory[80]

- Philip Guston[2]: 161

- Irving Guyer[81]

- Abraham Harriton[82]

- Marsden Hartley[2]: 161

- Knute Heldner[83]

- August Henkel[84]

- Ralf Henricksen[85]

- Magnus Colcord Heurlin[58]

- Hilaire Hiler[38]: 145

- Louis Hirshman[86][87]

- Donal Hord[88]

- Axel Horn[89]

- Milton Horn[90]

- Allan Houser[35]

- Eitaro Ishigaki[91]

- Edwin Boyd Johnson[38]: 140

- Sargent Claude Johnson[92]

- Tom Loftin Johnson[93]

- William H. Johnson[94]

- Leonard D. Jungwirth[57]

- Reuben Kadish[95]

- Sheffield Kagy[96]

- Jacob Kainen[97]

- David Karfunkle[98]

- Leon Kelly[38]: 145

- Paul Kelpe[43]

- Troy Kinney[58]

- Georgina Klitgaard[38]: 145

- Gene Kloss[38]: 154

- Karl Knaths[38]: 141, 146

- Edwin B. Knutesen[99]

- Lee Krasner[100]

- Kalman Kubinyi[101]

- Yasuo Kuniyoshi[38]: 154

- Jacob Lawrence[2]: 161

- Edward Laning[38]: 141

- Michael Lantz[102]

- Blanche Lazzell[38]: 154

- Tom Lea[103]

- Lawrence Lebduska[38]: 146

- Joseph Leboit[104]

- William Robinson Leigh[35]

- Julian E. Levi[38]: 146

- Jack Levine[38]: 146

- Monty Lewis[105]

- Elba Lightfoot[106]

- Abraham Lishinsky[38]: 141

- Michael Loew[107]

- Thomas Gaetano LoMedico[108]

- Louis Lozowick[2]: 168, 171

- Nan Lurie[38]: 155

- Guy Maccoy[109]

- Stanton Macdonald-Wright[110]

- George McNeil[38]: 144

- Moissaye Marans[111]

- David Margolis[112]

- Kyra Markham[38]: 155

- Jack Markow[113]

- Mercedes Matter[114]

- Jan Matulka[38]: 144

- Dina Melicov[115]

- Hugh Mesibov[116]

- Katherine Milhous[38]: 163

- Jo Mora[117]

- Helmuth Naumer[35]

- Louise Nevelson[118]

- James Michael Newell[119]

- Spencer Baird Nichols[58]

- Elizabeth Olds[120]

- John Opper[121]

- William C. Palmer[38]: 142 [122]

- Phillip Pavia[58]

- Irene Rice Pereira[123]

- Jackson Pollock[124]

- George Post[38]: 150

- Gregorio Prestopino[38]: 147

- Mac Raboy[125]

- Anton Refregier[38]: 155

- Ad Reinhardt[126]

- Misha Reznikoff[38]: 147

- Mischa Richter[58]

- Diego Rivera[127]

- José de Rivera[128]

- Emanuel Glicen Romano[129]

- Mark Rothko[2]: 161

- Alexander Rummler[58]

- Augusta Savage[130][131]

- Concetta Scaravaglione[38]: 157

- Louis Schanker[132]

- Edwin Scheier[133]

- Mary Scheier[133]

- Carl Schmitt[58]

- William S. Schwartz[38]: 147

- Georgette Seabrooke[134]

- Ben Shahn[135][136]

- William Howard Shuster[137]

- Mitchell Siporin[138]

- John French Sloan[6]

- Joseph Solman[139]

- William Sommer[38]: 151

- Isaac Soyer[140]

- Moses Soyer[2]: 161

- Raphael Soyer[2]: 32

- Ralph Stackpole[141]

- Cesare Stea[142]

- Walter Steinhart[58]

- Joseph Stella[2]: 175

- Harry Sternberg[2]: 167

- Sakari Suzuki[143]

- Albert Swinden[43][144]

- Rufino Tamayo[38]: 151

- Elizabeth Terrell[38]: 147

- Lenore Thomas[2]: 323

- Dox Thrash[4]: 373

- Mark Tobey[2]: 161 [54]

- Harry Everett Townsend[58]

- Edward Buk Ulreich[48]

- Charles Umlauf[145]

- Jacques Van Aalten[146]

- Stuyvesant Van Veen[147]

- Herman Volz[148]

- Mark Voris[149]

- John Augustus Walker[150]

- Andrew Winter[6]

- Jean Xceron[151]

- Edgar Yaeger[152]

- Bernard Zakheim[153][154]

- Karl Zerbe[38]: 148

Community Art Center program

[edit]The first federally sponsored community art center opened in December 1936 in Raleigh, North Carolina.[155]

| State | City | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Birmingham | Extension art gallery[4]: 441 | |

| Alabama | Birmingham | Healey School Art Gallery | [4]: 441 |

| Alabama | Mobile | Mobile Art Center, Public Library Building | [4]: 441 |

| Arizona | Phoenix | Phoenix Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| District of Columbia | Washington, D.C. | Children's Art Gallery | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Bradenton | Bradenton Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Coral Gables | Coral Gables Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 441 |

| Florida | Daytona Beach | Daytona Beach Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Beach Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 441 |

| Florida | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Negro Art Center | Extension art gallery[4]: 441 [156] |

| Florida | Key West | Key West Community Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Miami | Miami Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Milton | Milton Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 441 |

| Florida | New Smyrna Beach | New Smyrna Beach Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Ocala | Ocala Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | Pensacola | Pensacola Art Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | St. Petersburg | Jordan Park Negro Exhibition Center | [4]: 441 |

| Florida | St. Petersburg | St. Petersburg Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Florida | St. Petersburg | St. Petersburg Civic Exhibition Center | [4]: 442 |

| Florida | Tampa | Tampa Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Florida | Tampa | West Tampa Negro Art Gallery | [4]: 442 |

| Illinois | Chicago | Hyde Park Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Illinois | Chicago | South Side Community Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Iowa | Mason City | Mason City Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Iowa | Ottumwa | Ottumwa Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Iowa | Sioux City | Sioux City Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Kansas | Topeka | Topeka Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Minnesota | Minneapolis | Walker Art Center | [4]: 442 [157] |

| Mississippi | Greenville | Delta Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Mississippi | Oxford | Oxford Art Center | [4]: 442 [158] |

| Mississippi | Sunflower | Sunflower County Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Missouri | St. Louis | The People's Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Montana | Butte | Butte Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| Montana | Great Falls | Great Falls Art Center | [4]: 442 |

| New Mexico | Gallup | Gallup Art Center | [4]: 443 [35] |

| New Mexico | Melrose | Melrose Art Center | [4]: 443 |

| New Mexico | Roswell | Roswell Museum and Art Center | [4]: 443 |

| New York City | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Community Art Center | [4]: 443 |

| New York City | Manhattan | Contemporary Art Center | [4]: 443 [159] |

| New York City | Harlem | Harlem Community Art Center | [4]: 443 |

| New York City | Flushing, Queens | Queensboro Community Art Center | [4]: 443 |

| North Carolina | Cary | Cary Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| North Carolina | Greensboro | Greensboro Art Center | [155] |

| North Carolina | Greenville | Greenville Art Gallery | [4]: 443 |

| North Carolina | Raleigh | Crosby-Garfield School | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| North Carolina | Raleigh | Needham B. Broughton High School | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| North Carolina | Raleigh | Raleigh Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| North Carolina | Wilmington | Wilmington Art Center | [4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Bristow | Bristow Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Claremore | Claremore Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Claremore | Will Rogers Public Library | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Clinton | Clinton Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Cushing | Cushing Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Edmond | Edmond Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Marlow | Marlow Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma Art Center | [4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Okmulgee | Okmulgee Art Center | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Sapulpa | Sapulpa Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Shawnee | Shawnee Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oklahoma | Skiatook | Skiatook Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 443 |

| Oregon | Gold Beach | Curry County Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Oregon | La Grande | Grande Ronde Valley Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Oregon | Salem | Salem Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Pennsylvania | Somerset | Somerset Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Tennessee | Chattanooga | Hamilton County Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Tennessee | Memphis | LeMoyne Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Tennessee | Nashville | Peabody Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Tennessee | Norris | Anderson County Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Utah | Cedar City | Cedar City Art Exhibition Association | Extension art gallery[4]: 444 |

| Utah | Helper | Helper Community Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 444 |

| Utah | Price | Price Community Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 444 |

| Utah | Provo | Provo Community Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 444 |

| Utah | Salt Lake City | Utah State Art Center | [4]: 444 |

| Virginia | Altavista | Altavista Extension Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Virginia | Big Stone Gap | Big Stone Gap Art Gallery | [4]: 444 |

| Virginia | Lynchburg | Lynchburg Art Gallery | [4]: 444 |

| Virginia | Richmond | Children's Art Gallery | [4]: 444 |

| Virginia | Saluda | Middlesex County Museum | Extension art gallery[4]: 444 |

| Washington | Chehalis | Lewis County Exhibition Center | Extension art gallery[4]: 444 |

| Washington | Pullman | Washington State College | Extension art gallery[4]: 444 |

| Washington | Spokane | Spokane Art Center | [4]: 444 [160] |

| West Virginia | Morgantown | Morgantown Art Center | [4]: 445 |

| West Virginia | Parkersburg | Parkersburg Art Center | [4]: 445 |

| West Virginia | Scotts Run | Scotts Run Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Casper | Casper Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Lander | Lander Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Laramie | Laramie Art Center | [4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Newcastle | Lander Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Rawlins | Rawlins Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Riverton | Riverton Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Rock Springs | Rock Springs Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Sheridan | Sheridan Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

| Wyoming | Torrington | Torrington Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[4]: 445 |

Index of American Design

[edit]

As we study the drawings of the Index of American Design we realize that the hands that made the first two hundred years of this country's material culture expressed something more than untutored creative instinct and the rude vigor of a frontier civilization. … The Index, in bringing together thousands of particulars from various sections of the country, tells the story of American hand skills and traces intelligible patterns within that story.

The Index of American Design program of the Federal Art Project produced a pictorial survey of the crafts and decorative arts of the United States from the early colonial period to 1900. Artists working for the Index produced nearly 18,000 meticulously faithful watercolor drawings,[2]: 226 documenting material culture by largely anonymous artisans.[161]: ix Objects surveyed ranged from furniture, silver, glass, stoneware and textiles to tavern signs, ships's figureheads, cigar-store figures, carousel horses, toys, tools and weather vanes.[2]: 224 [162] Photography was used only to a limited degree since artists could more accurately and effectively present the form, character, color and texture of the objects. The best drawings approach the work of such 19th-century trompe-l'œil painters as William Harnett; lesser works represent the process of artists who were given employment and expert training.[161]: xiv

"It was not a nostalgic or antiquarian enterprise," wrote historian Roger G. Kennedy. "It was initiated by modernists dedicated to abstract design, hoping to influence industrial design — thus in many ways it parallelled the founding philosophy of the Museum of Modern Art in New York."[2]: 224

Like all WPA programs, the Index had the primary purpose of providing employment.[163] Its function was to identify and record material of historical significance that had not been studied and was in danger of being lost. Its aim was to gather together these pictorial records into a body of material that would form the basis for organic development of American design — a usable American past accessible to artists, designers, manufacturers, museums, libraries and schools. The United States had no single comprehensive collection of authenticated historical native design comparable to those available to scholars, artists and industrial designers in Europe.[164]

"In one sense the Index is a kind of archaeology," wrote Holger Cahill. "It helps to correct a bias which has tended to relegate the work of the craftsman and the folk artist to the subconscious of our history where it can be recovered only by digging. In the past we have lost whole sequences out of their story, and have all but forgotten the unique contribution of hand skills in our culture."[161]: xv

The Index of American Design operated in 34 states and the District of Columbia from 1935 to 1942. It was founded by Romana Javitz, head of the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library, and textile designer Ruth Reeves.[2]: 224 Reeves was appointed the first national coordinator; she was succeeded by C. Adolph Glassgold (1936) and Benjamin Knotts (1940). Constance Rourke was national editor.[161]: xii The work is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[165]

The Index employed an average of 300 artists during its six years in operation.[161]: xiv One artist was Magnus S. Fossum, a longtime farmer who was compelled by the Depression to move from the Midwest to Florida. After he lost his left hand in an accident in 1934, he produced watercolor renderings for the Index, using magnifiers and drafting instruments for accuracy and precision. Fossum eventually received an insurance settlement that made it possible for him to buy another farm and leave the Federal Art Project.[2]: 228

In her essay,'Picturing a Usable Past,' Virginia Tuttle Clayton, curator of the 2002-2003 exhibition, Drawing on America's Past: Folk Art, Modernism, and the Index of American Design, held at the National Gallery of Art noted that "the Index of American Design was the result of an ambitious and creative effort to furnish for the visual arts a usable past."[166]

-

Panel from reredos at the Church of Sanctuario at Chimayo

-

Fly Catcher, 1937. Frank McEntee. National Gallery of Art

-

Magnus Fossum copying the 1770 Boston Town Coverlet (February 1940)

-

Boston Town Coverlet

Magnus Fossum (1935–1942) -

Poke Bonnet,Irene Lawson. Index of American Design. National Gallery of Art

-

Daguerreotype Case Index of American Design

-

"Age of Chivalry" Circus Wagon, c. 1938

-

Noah's Ark with animals

Poster Division

[edit]

The WPA Poster Division was headed by Richard Floethe.[167] The WPA Poster Division is thought to have produced upward of 35,000 designs and printed some two million posters, originally by hand but quickly transitioning to widespread adoption of the silkscreen process.[168][167] The Poster Division began in New York City and by 1938 had artists in 18 states; the Chicago unit was the second-most productive after New York.[167] According to preeminent New Deal art historian Francis V. O’Connor, only about 2,000 surviving examples of WPA poster art are held in the nation’s library and museum print collections.[167]

WPA Art Recovery Project

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Hundreds of thousands of artworks were commissioned under the Federal Art Project.[6] Many of the portable works have been lost, abandoned, or given away as unauthorized gifts. As custodian of the work, which remains federal property, the General Services Administration (GSA) maintains an inventory[170] and works with the FBI and art community to identify and recover WPA art.[171] In 2010, it produced a 22-minute documentary about the WPA Art Recovery Project, "Returning America’s Art to America", narrated by Charles Osgood.[172]

In July 2014, the GSA estimated that only 20,000 of the portable works have been located to date.[170][173] In 2015, GSA investigators found 122 Federal Art Project paintings in California libraries, where most had been stored and forgotten.[174]

See also

[edit]- List of Federal Art Project artists

- Section of Painting and Sculpture

- Public Works of Art Project

- Farm Security Administration which employed photographers.

References

[edit]- ^ Laning, Edward (1970-10-01). "When Uncle Sam Played Patron of the Arts: Memoirs of a WPA Painter". American Heritage. 21 (6). Retrieved 2022-10-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Kennedy, Roger G.; Larkin, David (2009). When Art Worked: The New Deal, Art, and Democracy. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8478-3089-3.

- ^ "Employment and Activities poster for the WPA's Federal Art Project, 1936". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq Kalfatovic, Martin R. (1994). The New Deal Fine Arts Projects: A Bibliography, 1933–1992. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-2749-2. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ a b c Brenner, Anita (April 10, 1938). "America Creates American Murals". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ a b c d e Naylor, Brian (April 16, 2014). "New Deal Treasure: Government Searches For Long-Lost Art". All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "New Deal Artwork: GSA's Inventory Project". General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2017-07-20. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ Atkins, Robert (1993). ArtSpoke: A Guide to Modern Ideas, Movements, and Buzzwords, 1848-1944. Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-1-55859-388-6.

- ^ a b c Whaley, K. P. (April 30, 2014). "Depression-Era Milwaukee Handicraft Project Put Thousands of People to Work". The Kathleen Dunn Show. Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ "WPA – Milwaukee Handicraft Project". Museum of Wisconsin Art. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ Roosevelt, Eleanor (November 13, 1936). "My Day". Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. The George Washington University. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "WPA Milwaukee Handicraft Project". School of Continuing Education, Employment and Training Institute. University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. Archived from the original on 2019-11-02. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ "WPA Art Project". Library. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ Smithsonian. Archives of American Art. George Godfrey Thorp papers, 1941–1970

- ^ Ehrich, Nancy and Roger. "William Ernst Ehrich Biography". Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Oral history interview with William Abbenseth". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. November 23, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Background". Changing New York. New York Public Library. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Gertrude Abercrombie papers". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-11.

- ^ "The Artist and His Life". The Artwork of Benjamin Abramowitz (1917–2011). S.A. Rosenbaum & Associates. Archived from the original on 2015-08-12. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Abe Ajay, Industry". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. July 27, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Charles Henry Alston". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. September 28, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ a b "The Artists of Buffalo's Willert Park Courts Sculptures". Western New York Heritage Press. Archived from the original on 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Luis Arenal". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. August 7, 1936. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "Pacific Grove High School Mural – Pacific Grove CA". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "George Washington High School: Arnautoff Mural – San Francisco CA". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Sheva Ausubel". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. March 30, 1937. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Jozef and Teresa Bakos, 1965". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ^ "Henry W. Bannarn, ca. 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Belle Baranceanu (1902-1988)". San Diego History Center. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Patrociño Barela". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. July 2, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Will Barnet, Labor". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Richmond Barthe, 1941 Apr. 4". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "William and Ethel Baziotes papers, 1916–1992". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ a b c d e f "WPA Art Collection – Gallup NM". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-07-19.

- ^ Edward Alden Jewell (August 27, 1933). "“Musings Way Down east,” New York Times"

- ^ "Bellis, Daisy Maud". Connecticut State Library. 27 August 1933. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Cahill, Holger (1936). Barr, Alfred H. Jr. (ed.). New Horizons in American Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art. OCLC 501632161.

- ^ Abbott, Leala (December 2004). "Arts and Culture, Art Center records 1930–2004, Finding Aid". Milstein/Rosenthal Center for Media & Technology. 92nd Street Y. Archived from the original on 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Leon Bibel: Art, Activism, and the WPA". Lora Robins Gallery of Design from Nature. University of Richmond. Archived from the original on 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Lucile Blanch, 1940 Oct. 31". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "1939 World's Fair Mural Study – Chicago IL". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- ^ a b c d "Williamsburg Housing Development Murals – Brooklyn NY". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Adele Brandeis". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. June 1, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ "Louise Brann, ca. 1935". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Manuel Bromberg, 1939 Jan. 23". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Oral history interview with James Brooks". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. June 10–12, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ a b "Bailey, Chief Librarian, Praises WPA Art Project". Long Island Sunday Press. Long Island, New York. April 5, 1936.

- ^ "Selma Burke". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Letterio Calapai, ca. 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Giorgio Cavallon, 1974". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ^ "P.S. 150 Mural – Queens NY". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- ^ "Dane Chanase, 1942 Jan. 26". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ a b c d Mahoney, Eleanor (2012). "The Federal Art Project in Washington State". The Great Depression in Washington State. Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Project, University of Washington. Retrieved 2015-06-23.

- ^ "Claude Clark Sr., In the Groove". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ^ "Max Arthur Cohn". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- ^ a b "Recovering America's Art for America". General Services Administration. 2010. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Artists". WPA Art Inventory Project. Connecticut State Library. Archived from the original on 2015-07-04. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ^ "Artist: Alfred D. Crimi". The Living New Deal. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ "Francis Criss, 1940 Oct. 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "History and Mission". About Us. Phoenix Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ Conn, Charis (February 15, 2013). "Art in Public: Stuart Davis on Abstract Art and the WPA, 1939". Annotations: The NEH Preservation Project. WNYC. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Adolf Dehn, 1940 Oct. 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Burgoyne Diller". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. October 2, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Isami Doi, Near Coney Island". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "Ruth Egri, 1937 Apr. 12". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Fritz Eichenberg, April". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "George Pearse Ennis, ca. 1936". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Angna Enters, 1940 Nov. 18". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Louis Ferstadt, 1939 Jan. 25". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "Alexander Finta, 1939 June 14". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Federal Art Project, Photographic Division collection, circa 1920–1965, bulk 1935–1942". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ Hughes, Edan Milton (1986). Artists in California, 1786-1940. San Francisco, CA: Hughes Publishing Company. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-9616112-0-0 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Activist Arts". A New Deal for the Arts. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Eugenie Gershoy, 1938 Mar. 28". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Enrico Glicenstein, 1940 Sept. 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Vincent Glinsky, 1939 Mar. 8". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Bertram Goodman, ca. 1939". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Marion Greenwood, 1940 June 4". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Waylande Gregory". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. June 2, 1937. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Irving Guyer, Reading by Lamplight". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Abraham Harriton, 1938 Aug. 16". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ Megraw, Richard (January 10, 2011). "Federal Art Project". KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ "August Henkel, ca. 1939". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Ralf C. Henricksen, 1938". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Service on the home front There's a job for every Pennsylvanian in these civilian defense efforts". Library of Congress. 1941.

- ^ "Stop and get your free fag bag Careless matches aid the Axis". Library of Congress. 1941.

- ^ "Donal Hord, 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Axel Horr [sic], 1940 June 28". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Milton Horn, c. 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Eitaro Ishigaki, ca. 1940". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Sargent Claude Johnson, Dorothy C.". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Tom Loftin Johnson, 1938". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "William H. Johnson: A Guide for Teachers". American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2015-06-13. Retrieved 2015-06-11.

- ^ "Reuben Kadish, Conversation with a Quarry Master". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Sheffield Kagy, Symphony Conductor". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Jacob Kainen, Rooming House". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "David Karfunkle, ca. 1938". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "WPA - Works Progress Administration - New Deal Artists | MOWA Online Archive". wisconsinart.org.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Lee Krasner". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. November 2, 1964 – April 11, 1968. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Kalman Kubinyi, Skaters". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Michael Lantz". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "New Mexico State University: Branson Library Art – Las Cruces NM". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- ^ "Joseph Leboit, Tranquility". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "Monty Lewis, 1938 May 26". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Elba Lightfoot, 1938 Jan. 14". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "Murals Approved of 5 WPA Artists". The New York Times. October 28, 1935. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ "Thomas Gaetano Lo Medico, 1938 May 12". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Guy and Genoi Pettit Maccoy". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. July 24, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "Federal Art Project Artists, 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Moissaye Marans, ca. 1939". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "David Margolis, 1940 May 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "Jack Markow, Street in Manasquan". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Mercedes Matter Interview Excerpts". Hans Hofmann: Artist/Teacher, Teacher/Artist. PBS. 2003. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Dina Melicov, 1939 Apr. 26". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Hugh Mesibov". National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ "King City High School Auditorium Bas Reliefs – King City CA". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Louise Nevelson". Guggenheim Collection Online. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "James Michael Newell, ca. 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Elizabeth Olds, 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ Mary Ann Marger (1990-05-07). "Thinking in the Abstract Series". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. p. 1D.

- ^ "William C. Palmer, 1936". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Irene Rice Pereira, 1938 Aug. 22". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Jackson Pollock". Guggenheim Collection Online. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-05-30. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Mac Raboy, Hitchhiker". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Ad Reinhardt". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "City College of San Francisco: Rivera Mural – San Francisco CA". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Oral history interview with José de Rivera". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. February 24, 1968. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ "Emanuel Glicen Romano, 1936 Nov. 23". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ "Augusta Savage". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- ^ "The Harp by Augusta Savage". 1939 NY World's Fair. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Louis Schanker". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. 1963. Retrieved 2015-06-11.

- ^ a b "Edwin & Mary Scheier". New Hampshire State Council on the Arts. February 12, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (September 16, 2012). "At Harlem Hospital, Murals Get a New Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Ben Shahn". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. October 3, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "Rikers Island WPA Murals – East Elmhurst NY". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Will Shuster, 1964". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ^ "Lane Tech College Prep High School Auditorium Mural – Chicago IL". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Joseph Solman". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "Isaac Soyer, A Nickel a Shine". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "George Washington High School: Stackpole Mural – San Francisco CA". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Cesare Stea, 1939 Mar. 2". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Sakari Suzuki, 1936 Dec. 2". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-14.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (November 5, 2014). "At Future Cornell Campus, the First Step in Restoring Murals Is Finding Them". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Timeline under Charles Umlauf bio on the UMLAUF Website".

- ^ "Jacques Van Aalten, 1938 May 26". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Stuyvesant Van Veen papers, circa 1926-1988". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Herman Roderick Volz, Lockout". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Mark Voris, 1965 February 11". www.aaa.si.edu.

- ^ "Murals by John Augustus Walker on permanent display in the Museum of Mobile lobby, Mobile, Alabama". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "Jean Xceron, 1942 Jan. 13". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ "Edgar L. Yaeger papers, 1923-1989". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "California Federal Art Project papers, 1935-1964". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-23.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (February 27, 2015). "UCSF to let public see trove of medical history murals". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2015-06-23.

- ^ a b Parker, Thomas C. (October 15, 1938). "Federally Sponsored Community Art Centers". Bulletin of the American Library Association. 32 (11). American Library Association: 807. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ "Children drawing at the Jacksonville Negro Art Center of the WPA Federal Art Project- Jacksonville, Florida". Florida Memory. State Library and Archives of Florida. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ Rash, John (January 30, 2015). "The Walker's WPA roots are still relevant today". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ^ Grieve, Victoria (2009). The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780252034213.

- ^ Abbott, Leala (December 2004). "Arts and Culture, Art Center records 1930–2004, Finding Aid". Milstein/Rosenthal Center for Media & Technology. 92nd Street Y. Archived from the original on 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

In 1935 and 1936, 92Y, in cooperation with the federal Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.) and the New York City Board of Education, began offering free courses … The Contemporary Art Center, part of the W.P.A.'s Federal Art Project, offered daytime courses for serious art students and was led by Nathaniel Dirk.

- ^ Mahoney, Eleanor (2012). "The Spokane Arts Center: Bringing Art to the People". The Great Depression in Washington State. Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Project, University of Washington. Retrieved 2015-06-23.

- ^ a b c d e f Cahill, Holger (1950). "Introduction". In Christensen, Erwin O. (ed.). The Index of American Design. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. ix–xvii. OCLC 217678.

- ^ Herzberg, Max (October 15, 1950). "American Craftsmanship Offers Beauty and Utility". Newark Evening News.

- ^ Jones, Louis C. (October 22, 1950). "Only Yesterday It Was Wooden Indians and Whittled Toys". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ Jewell, Edward Alden (March 19, 1939). "Saving Our Usable Past". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "History". Index of American Design. National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ^ Drawing on America's Past: Folk Art, Modernism, and the Index of American Design by Virginia Tuttle Clayton, Elizabeth Stillinger, Erika Doss, and Deborah Chotner. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2002.

- ^ a b c d DeNoon, Christopher (1987). Posters of the WPA. Francis V. O'Connor. Los Angeles: Wheatley Press, in association with the University of Washington Press, Seattle. ISBN 0-295-96543-6. OCLC 16558529.

- ^ Carter, Ennis (2008). Posters for the people : art of the WPA. Christopher DeNoon, Alexander M. Peltz. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books. ISBN 978-1-59474-292-7. OCLC 227919759.

- ^ "Works Progress Administration (WPA) Art Recovery Project". General Services Administration. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ a b "New Deal Artwork: GSA's Inventory Project". General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2017-07-20. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "New Deal Artwork: Ownership and Responsibility". General Services Administration. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "Works Progress Administration (WPA) Art Recovery Project". Office of the Inspector General, General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ MacFarlane, Scott (September 17, 2014). "Lost History: Hunting for WPA Paintings". NBC 4. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ MacFarlane, Scott (April 20, 2015). "Dozens of Pieces of Lost WPA Art Found in California". NBC 4. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

Further reading

[edit]- DeNoon, Christopher. Posters of the WPA (Los Angeles: Wheatley Press, 1987).

- Grieve, Victoria. The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture (2009) excerpt

- Kennedy, Roger G.; David Larkin (2009). When art worked. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-3089-3.

- Kelly, Andrew, Kentucky by Design: American Culture, the Decorative Arts and the Federal Art Project's Index of American Design, University Press of Kentucky, 2015, ISBN 978-0-8131-5567-8

- Russo, Jillian. "The Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project Reconsidered." Visual Resources 34.1-2 (2018): 13-32.

External links

[edit]- The Living New Deal research project and online public archive at the University of California, Berkeley

- Recovering America's Art for America (2010), General Services Administration short documentary about efforts to recover WPA art

- Posters for the People, online archive of WPA posters

- WPA Posters collection at the Library of Congress

- New Deal Art Registry

- wpamurals.com Archived 2012-12-05 at archive.today – links to each state, with examples of WPA art in each

- Federal Art Project Photographic Division collection at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- "1934: A New Deal for Artists" Exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

- “Art Within Reach”: Federal Art Project Community Art Centers at George Mason University

- WPA Murals and American Abstract Artists at American Abstract Artists

- WPA Prints and Murals in New York

- Collection: "Art of the Works Progress Administration WPA" from the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- WNYC and the WPA Federal Art Project