This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2021) |

| |

| Use | National flag, civil and state ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 6 March 1957 |

| Design | A horizontal triband of the Ethiopian Pan-African colors of red, gold, and green, charged with a black star in the centre |

| Designed by | Theodosia Okoh |

| |

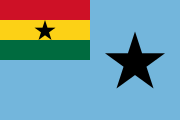

| Use | Civil ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Design | A red field with the national flag, fimbriated in black, in the canton |

| |

| Use | Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Design | Red English St. George's Cross on white centrrensign, with the national flag in canton. |

The national flag of Ghana consists of a horizontal triband of red, yellow, and green. It was designed in replacement of the British Gold Coast's Blue Ensign.[1]

The flag, which was adopted upon the independence of the Dominion of Ghana on 6 March 1957, was designed that same year by Theodosia Okoh, a renowned Ghanaian artist.[2][3][4][5] The flag was flown from the time of Ghana's independence until 1962,[6] then reinstated in 1966 after Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown by coup d'état. in February 1966. The flag of Ghana consists of the Ethiopian Pan-African colours of red, gold, and green in horizontal stripes with a black five-pointed star in the centre of the gold stripe. The Ghanaian flag was the second African flag after the flag of the Ethiopian Empire to feature the red, gold, and green colours, although these colours are inverted. The design of the Ghanaian flag influenced the designs of the flags of Guinea-Bissau (1973) and São Tomé and Príncipe (1975).

Design

[edit]The Ghanaian flag was designed as a tricolour of red, gold and green with a black star in the centre.[7]

The red colour of the flag represents the blood of forefathers who led the struggle of independence from British colonial rule.[8] This claimed the lives of the 'big six', Ghanaian leaders Edward Akufo Addo, Dr. Ako Adjei, William Ofori Atta, Joseph Boakye Danquah, Emmanuel Obetsebi Lamptey, and later Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah,[9] who formed the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC),[10][11][12] an anti-colonialist political party.[13] Red is also interpreted to stands for the love of the Ghanaian nation.[14]

The gold colour represents the wealth imbued by mineral resources mostly found in Obuasi in Ashanti Region and Tarkwa in the Western Region.[15][16] The gold in Ghana led to the initial name of the Gold Coast, which was later changed to Ghana upon independence in 1957.[17] Ghana's other mineral resources are diamond, bauxite, and manganese.[18]

The green symbolises Ghana's forests and natural wealth[19] which provide the nation with oil, food, and crops such as cocoa, timber, Shea Butter.[20][21][22] Most of Ghana's crops are exported to overseas countries in exchange for physical cash which is used for the country's development of roads, schools, water, sanitation and industries for employment.[23]

The black star of the Ghanaian national flag is a symbol for the emancipation of Africa and unity against colonialism.[24][25] The black star was adopted from the flag of the Black Star Line, a shipping line incorporated by Marcus Garvey which operated from 1919 to 1922.[26] It became also known as the Black Star of Africa. It is also where the Ghana national football team derived their nickname, the "Black Stars".

Colour scheme |

Red | Yellow | Green | Black |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMYK | 0-96-84-19 | 0-17-94-1 | 100-0-43-58 | 100-100-100-99 |

| HEX | #CF0921 | #FCD20F | #006B3D | #000000 |

| RGB | 207-9-33 | 252-210-15 | 0-107-61 | 0-0-0 |

Ghana's struggle for independence before the national flag

[edit]Ghana was one of the countries counted among the West African regions under colonial government rule from the 15th to 19th centuries on the Gold Coast. The history of Ghana can therefore be traced back to the 15th century when Europeans arrived in the region.[27][28] The Portuguese navigators sailed their way down the West African coast and to the shores of the Gold Coast in 1471, where they built a castle for themselves at Elmina in 1482.[29] Other Europeans followed in 1492 to include the sailor from France.[clarification needed] The Europeans brought gold cargo to the shores of the Gold Coast where they traded in gold with the Akwamus and Denkyira who controlled an extensive part of the coast and the forest belt in the 17th century.[30]

In the 18th century, the dominance of the Ashanti Empire of Kumasi took over the gold trade with the British, Dutch and Danes who were the main European traders at the Tano and Volta rivers.[31] The most valuable commodity for exports at the time changed from gold to slaves. Slaves were traded for muskets besides other Western commodities. The Ashantes by then were locally empowered to take control with the Asantehene enthroned on a golden stool as a tradition of the Ashantes. Between 1804 and 1814, the British, Dutch and Danes subsequently outlawed the slave trade, which proved to be a major blow to the Ashanti economy.[32][33][34] Because of the situation, wars were fought in 1820, 1824 and 1870, they were subsequently defeated by British forces who shortly thereafter occupied the region of Kumasi in 1874. The British gradually emerged in the coastal regions as the main European power.[35][36]

The colonial period started from 1902 to 1957. The Ashante Kingdom in 1902 was declared a British crown colony and became the protectorate of the northern territory of the Gold Coast. The colonial government ruled the colony without the involvement of the African populace in the political process. After World War II, the Gold Coast colony became prominent among the Sub-Saharan African countries.[37][38][39] It was when Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in 1947 after twelve years of political study in the US and Great Britain. The return to the Gold Coast was an invitation for Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah to lead the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) as the General Secretary to lead the campaign for self-government. The UGCC at the time had won the right of the African majority in the British legislative colony. With the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah, a widespread riot began in February 1948.[40][41]

Within the same year, the founding leaders of the UGCC arrested Secretary General Dr. Kwame Nkrumah for an alert of thoughts against Nkrumah's leadership plans. The incident brought a split of the UGCC leadership with Kwame Nkrumah having to found his own Convention People's Party (CPP) in June 1949 for the aim of self-governance for the African people, dubbed "Self-government now". A non-violent campaign of protest and strikes was organised by Kwame Nkrumah in 1950 to achieve his goal.[42][43][44] But the riot led to the second arrest of Kwame Nkrumah.[45] The colony's general election brought a big win to the Convention People's Party in the absence of Kwame Nkrumah, leading to the release of Kwame Nkrumah from prison to join in the governance of the country. Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah then became the Prime Minister of the Gold Coast in 1952.[40] In a vote of the 1956 direct vote of all the electorate members, the British Togoland voted to join the Gold Coast in the campaign for preparations towards independence.[46] The Togo and Gold Coast territories attained independence from colonial rule in 1957 under the supreme willpower of Kwame Nkrumah. The name for the country Ghana was then adopted.[47][48]

The years of independence of the Gold Coast started in 1957 with the new name of the country of Ghana emerged.[17] Independence was granted and announced by the then Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah who led the struggle for independence.[40] With Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah as the first President of Ghana, Ghana became a Republic within the Commonwealth of Nations on 1 July 1960.[49]

Theodosia Okoh (The national flag's designer)

[edit]Theodosia Salome Abena Kumea Okoh was a renowned Ghanaian artist who has contested and showcased her artistic internationally.[50] She joined the Ghana Hockey Association (GHA) and worked in the role of a chairperson. She was also a patron of the Sports Writer's Association of Ghana (SWAG).[51][2]

Purpose and use of the Ghanaian national flag

[edit]The purpose of the Ghanaian national flag was to be a symbol of jubilation during the post-independence era.[52] There were many flags ensembled for Ghana's use. Notably, the Ghanaian national flag described which has been used for many purposes in national and international celebrations, such as the Independence Day Celebration, commemoration of Ghana's Big Six and past leaders of the nations.[53] The flag is raised up flying in the sky to grace glorious occasions while it is usually lowered to fly halfway to show some kind of misfortune that may have hit on the country.[54]

National ensign

[edit]Under terms of section 183 of Ghana's Merchant Shipping Act of 1963, the civil ensign is a red flag with the national flag in a black-fimbriated canton. In 2003, a new merchant shipping act was enacted, however, and this simply provides that "the National Flag of Ghana" is the proper national colours for Ghanaian ships. No mention is made of other flags or other possible flags.[55][56]

The naval ensign is a red St. George's Cross on white flag, with the national flag in canton.

Air force ensign and civil air ensign

[edit]The Ghana Air Force has its own ensign that incorporates the flag of Ghana. Civil aviation in Ghana is represented by the national civil air ensign. It is a standard light-blue field with the Ghanaian flag in the canton. It is charged in the fly with either a red, yellow and green roundel (in the case of the military ensign) or black five-pointed star (in the case of the civil ensign). Both have been used since Independence in 1957, and the subsequent founding of the Ghana Air Force in 1959.[57]

History

[edit]-

Flag of the Gold Coast, the forerunner to Ghana. Used until 1957.

Flag of the Gold Coast, the forerunner to Ghana. Used until 1957. -

Second flag of the Union of African States, used between 1961 and 1963 (after Mali joined).

Second flag of the Union of African States, used between 1961 and 1963 (after Mali joined).

The Ghanaian government flag, adopted in 1957, was flown until 1962. Similarly, when the country formed the Union of African States, the flag of the Union was modeled on Bolivia's flag, but with two black stars, representing the nations. In May 1959, a third star was added.[58]

Following the January 1964 constitutional referendum, Ghana adopted a variant of the 1957 tricolour with white in the place of yellow, after the colours of Kwame Nkrumah's ruling and then-sole legal party Convention People's Party, making it similar to the flag of Hungary. The original 1957 flag was reinstated in February 1966 following Nkrumah's overthrow in the February 1966 coup d'état.[59]

When the flag was changed in 1964, popular public demand upon the remembrance of Ghana's rich history agitated for the nation to revert to its use of the original Ghanaian national flag with the red, gold and green colour.[60] The original Ghana national flag which was used in 1957 upon Ghana's independence was reinstated for use in 1966.[61] Ghana was then one of the first countries to adopt the Pan African colours originally used in the Ethiopian flag.[62][63]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Flag sequence (flag, FLAG, FLAG tag)", The Dictionary of Genomics, Transcriptomics and Proteomics, Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, p. 1, 2015-12-18, doi:10.1002/9783527678679.dg04454, ISBN 978-3-527-67867-9

- ^ a b "Mrs. Theodosia Salome Okoh". GhanaWeb. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ Celebs, African (2018-03-06). "Mrs Theodosia Okoh: The Woman Who Designed The Ghanaian Flag – African Celebs". Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Rich, Jeremy (2011-12-08), "Okoh, Theodosia Salome", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.49700, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1

- ^ Aikins, Ama de-Graft; Koram, Kwadwo (2017-02-16), "Health and Healthcare in Ghana, 1957–2017", The Economy of Ghana Sixty Years after Independence, Oxford University Press, pp. 365–384, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198753438.003.0022, ISBN 978-0-19-875343-8

- ^ "Ghana Flag & Coat of Arms".

- ^ Andrew, Geoff (1998), "Three Colours: Red", The 'Three Colours' Trilogy, British Film Institute, pp. 52–66, doi:10.5040/9781838712389.ch-005, ISBN 978-1-83871-238-9

- ^ "Dominguez, Don Vicente J., (died 28 June 1916), Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the Argentine Republic to Great Britain since 1911", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2007-12-01, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u195667

- ^ Akansina Aziabah, Maxwell (2011-12-08), "Obetsebi-Lamptey, Emmanuel Odarquaye", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.49678, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1

- ^ "Contact Downunder". Contact Dermatitis. 56 (3): 183. March 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00892.x. ISSN 0105-1873. S2CID 221578564.

- ^ Austin, Dennis (July 1961). "The Working Committee of the United Gold Coast Convention". The Journal of African History. 2 (2): 273–297. doi:10.1017/S0021853700002474. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 180002. S2CID 154611723.

- ^ "United Gold Coast Convention | political organization, Ghana". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ "Chapter 2. The Gold Coast", A New World of Labor, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 36–53, 2013, doi:10.9783/9780812208313.36, ISBN 978-0-8122-0831-3

- ^ Dankwa, Serena Owusua (2011). ""The One Who First Says I Love You": Same-Sex Love and Female Masculinity in Postcolonial Ghana". Ghana Studies. 14 (1): 223–264. doi:10.1353/ghs.2011.0007. ISSN 2333-7168. S2CID 142957798.

- ^ OSAE, Shiloh; KASE, Katsuo; YAMAMOTO, Masahiro (March 1999). "Ore Mineralogy and Mineral Chemistry of the Ashanti Gold Deposit at Obuasi, Ghana". Resource Geology. 49 (1): 1–11. Bibcode:1999ReGeo..49....1O. doi:10.1111/j.1751-3928.1999.tb00027.x. ISSN 1344-1698. S2CID 128544182.

- ^ Bowell, R. J. (December 1992). "Supergene gold mineralogy at Ashanti, Ghana: Implications for the supergene behaviour of gold". Mineralogical Magazine. 56 (385): 545–560. Bibcode:1992MinM...56..545B. doi:10.1180/minmag.1992.056.385.10. ISSN 0026-461X. S2CID 53135281.

- ^ a b Howe, Russell Warren (1957). "Gold Coast into Ghana". The Phylon Quarterly. 18 (2): 155–161. doi:10.2307/273187. ISSN 0885-6826. JSTOR 273187.

- ^ Patterson, Sam H. (1971). "Investigations of ferruginous bauxite and other mineral resources on Kauai and a reconnaissance of ferruginous bauxite deposits on Maui, Hawaii". Professional Paper. doi:10.3133/pp656. ISSN 2330-7102.

- ^ Owens, Alastair; Green, David R. (2016). "Historical geographies of wealth: opportunities, institutions and accumulation, c. 1800–1930". Handbook on Wealth and the Super-Rich: 43–67. doi:10.4337/9781783474042.00010. ISBN 9781783474042.

- ^ Osei-Bonsu, K; Amoah, FM; Oppong, FK (1998-01-01). "The establishment and early yield of cocoa intercropped with food crops in Ghana". Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science. 31 (1). doi:10.4314/gjas.v31i1.1944. ISSN 0855-0042.

- ^ Knight, John G; Clark, Allyson; Mather, Damien W (2013-07-09). "Potential damage of GM crops to the country image of the producing country". GM Crops & Food. 4 (3): 151–157. doi:10.4161/gmcr.26321. ISSN 2164-5698. PMID 24002524.

- ^ Green-Armytage, Paul (2019-08-08), "Seven Kinds of Colour", Colour for Architecture Today, Taylor & Francis, pp. 64–68, doi:10.4324/9781315881379-15, ISBN 978-1-315-88137-9, S2CID 187014914

- ^ Oduro, Razak (2014-11-03). "Beyond poverty reduction: Conditional cash transfers and citizenship in Ghana". International Journal of Social Welfare. 24 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1111/ijsw.12133. ISSN 1369-6866.

- ^ "Celebrating Theodosia Okoh, the woman who designed the Ghana Flag", GhanaWeb.

- ^ "Theodosia Salome Okoh, Ghana's Illustrious Daughter", Flex Newspaper, 29 January 2017.

- ^ Crampton, William George (1993). "Marcus Garvey and the Rasta colours". Report of the 13th International Congress of Vexillology, Melbourne, 1989. Flag Society of Australia. pp. 169–180. ISBN 0-646-14343-3.

- ^ Shumway, Rebecca (2018). "A Shared Legacy: Atlantic Dimensions of Gold Coast (Ghana) History in the Nineteenth Century". Ghana Studies. 21 (1): 41–62. doi:10.1353/ghs.2018.0003. ISSN 2333-7168. S2CID 166055920.

- ^ Horton, James Africanus Beale (2011), "Self-Government of the Gold Coast", West African Countries and Peoples, British and Native, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 104–123, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511983146.010, ISBN 978-0-511-98314-6

- ^ "Exits from Elmina Castle", Tender, University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 5–10, 1997, doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qh875.5, ISBN 978-0-8229-7852-7

- ^ Chalmers, AlbertJ. (November 1900). "Uncomplicated Æstivo-Autumnal Fever in Europeans in the Gold Coast Colony, West Africa". The Lancet. 156 (4027): 1262–1264. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)99958-1. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ^ "The Gold Coast at the End of the Seventeenth Century Under the Danes and Dutch". African Affairs. 4 (XIII): 1–32. October 1904. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a093856. ISSN 1468-2621.

- ^ Reese, Ashanté (November 2019). "Dear Graduate Student...". Anthropology News. 60 (6). doi:10.1111/an.1303. ISSN 1541-6151. S2CID 242489555.

- ^ Voss, Karsten; Weber, Klaus (2020-07-01). "Their Most Valuable and Most Vulnerable Asset". Journal of Global Slavery. 5 (2): 204–237. doi:10.1163/2405836x-00502004. ISSN 2405-8351. S2CID 225526297.

- ^ "The end of the Dutch slave trade, 1781–1815", The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600–1815, Cambridge University Press, pp. 284–303, 1990-05-25, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511528958.013, ISBN 978-0-521-36585-7

- ^ "Lowe, Percy Roycroft, (2 Jan. 1870–18 Aug. 1948), late President, British Ornithologists' Union; Chairman, European and British Sections International Committee for Preservation of Birds", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2007-12-01, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u228383

- ^ "Stewart, Captain Sir Donald William, (22 May 1860–1 Oct. 1905), Commissioner, East African Protectorate from 1904; British resident, Kumasi, retired", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2007-12-01, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u191258

- ^ "Sanitary Progress in the Gold Coast Colony". The Lancet. 159 (4111): 1710. June 1902. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)85617-8. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ^ Cyclical Behavior of Fiscal Policy among Sub-Saharan African Countries. 2016-08-24. doi:10.5089/9781513563541.087. ISBN 9781513563541.

- ^ "Acronyms used", Becoming Zimbabwe. A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008, Weaver Press, pp. viii–ix, 2009-09-15, doi:10.2307/j.ctvk3gmpr.6, ISBN 978-1-77922-121-6

- ^ a b c "Nkrumah, Dr Kwame, (21 Sept. 1909–27 April 1972)", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2007-12-01, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u158013

- ^ "Secretary of the Ugcc", Kwame Nkrumah. Vision and Tragedy, Sub-Saharan Publishers, pp. 52–72, 2007-11-15, doi:10.2307/j.ctvk3gm60.9, ISBN 978-9988-647-81-0

- ^ "HISTORY OF GHANA". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- ^ Rathbone, Richard; Nkrumah, Kwame; Milne, June (1991). "Kwame Nkrumah: The Conakry Years: His Life and Letters". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 24 (2): 471. doi:10.2307/219836. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 219836.

- ^ Amoh, Emmanuella (2019). Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality (Thesis). Illinois State University. doi:10.30707/etd2019.amoh.e.

- ^ Sayeed, Khalid Bin; Nkrumah, Kwame (1959). "The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah". International Journal. 14 (4): 324. doi:10.2307/40198684. ISSN 0020-7020. JSTOR 40198684.

- ^ Bedolla, Lisa García; Michelson, Melissa R. (2012-10-09), "Calling All Voters: Phone Banks and Getting Out the Vote", Mobilizing Inclusion, Yale University Press, pp. 55–85, doi:10.12987/yale/9780300166781.003.0003, ISBN 978-0-300-16678-1

- ^ "Prime Minister 1957–60", Kwame Nkrumah. Vision and Tragedy, Sub-Saharan Publishers, pp. 192–214, 2007-11-15, doi:10.2307/j.ctvk3gm60.17, ISBN 978-9988-647-81-0

- ^ Bradley, Kenneth (July 1957). "Ghana. The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah". International Affairs. 33 (3): 383. doi:10.2307/2605549. ISSN 1468-2346. JSTOR 2605549.

- ^ Rathbone, Richard (2004-09-23). "Nkrumah, Kwame (1909?–1972), president of Ghana". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31504. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Rich, Jeremy (2011-12-08), "Okoh, Theodosia Salome", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.49700, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1

- ^ Valls-Russell, Janice (2011-09-01). ""As she had some good, so had she many bad parts": Semiramis' Transgressive Personas". Caliban. 29 (29): 103–118. doi:10.4000/caliban.746. ISSN 2425-6250.

- ^ "Colonial administrators and post-independence leaders in Ghana (1850–2000)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005-09-22. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93238. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Colonial administrators and post-independence leaders in Ghana (1850–2000)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005-09-22. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93238. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "4. A Glorious Dress-up Chest: Genre", Guy Maddin's My Winnipeg, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 52–65, 2010-12-31, doi:10.3138/9781442694057-004, ISBN 978-1-4426-9405-7

- ^ "The Flag, and Other Flags". Scientific American. 4 (83supp): 1321. 1877-08-04. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican08041877-1321asupp. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ North Atlantic Fisheries Intelligence Group. (2018). Chasing Red Herrings : Flags of Convenience, Secrecy and the Impact on Fisheries Crime Law Enforcement. Nordic Council of Ministers. ISBN 978-92-893-5160-7. OCLC 1081106582.

- ^ National Civil Society Sustainability Strategy for Civil Society in Ghana (Report). 2019-01-01. doi:10.15868/socialsector.36966.

- ^ Gilmour, Rachael (2020-07-28), "The New Union Flag Project", Bad English, Manchester University Press, doi:10.7765/9781526108852.00005, ISBN 978-1-5261-0885-2

- ^ Bradley, Kenneth (1957). "Ghana. The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah". International Affairs. 33 (3): 383. doi:10.2307/2605549. ISSN 1468-2346. JSTOR 2605549.

- ^ Shumway, Rebecca (2018). "A Shared Legacy: Atlantic Dimensions of Gold Coast (Ghana) History in the Nineteenth Century". Ghana Studies. 21 (1): 41–62. doi:10.1353/ghs.2018.0003. ISSN 2333-7168. S2CID 166055920.

- ^ Gyimah-Boadi, Emmanuel (2007). "Politics in Ghana Since 1957: The Quest for Freedom, National Unity, and Prosperity". Ghana Studies. 10 (1): 107–143. doi:10.1353/ghs.2007.0004. ISSN 2333-7168.

- ^ Gyimah-Boadi, Emmanuel (2007). "Politics in Ghana Since 1957: The Quest for Freedom, National Unity, and Prosperity". Ghana Studies. 10 (1): 107–143. doi:10.1353/ghs.2007.0004. ISSN 2333-7168.

- ^ "Chapter One. Recognizing the Ethiopian Flag", Black Land, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 21–50, 2019-12-31, doi:10.1515/9780691194134-004, ISBN 978-0-691-19413-4, S2CID 243396385

External links

[edit]- Ghana at Flags of the World

- Armed Forces of Ghana Colours Archived 2016-03-13 at the Wayback Machine