| Flight of the Intruder | |

|---|---|

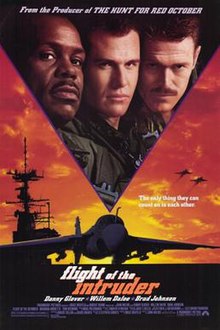

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Milius |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Flight of the Intruder by Stephen Coonts |

| Produced by | Mace Neufeld |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Fred J. Koenekamp |

| Edited by | Carroll Timothy O'Meara |

| Music by | Basil Poledouris |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[1] |

| Box office | $14,587,732 |

Flight of the Intruder is a 1991 war film directed by John Milius, and starring Danny Glover, Willem Dafoe, and Brad Johnson. It is based on the novel of the same name by former Grumman A-6 Intruder pilot Stephen Coonts. The film received negative reviews upon release, and was Milius's final theatrical release as a director.

Plot

[edit]Lieutenant Jake "Cool Hand" Grafton and his bombardier/navigator and best friend Lieutenant Morgan "Morg" McPherson are flying a Grumman A-6 Intruder during the Vietnam War over the Gulf of Tonkin towards North Vietnam. They hit their target, a 'suspected truck park', which actually turns out to be trees. On the return to carrier, Morg is fatally shot in the neck by an armed Vietnamese peasant. Landing on USS Independence with Morg dead, a disturbed Jake, covered in blood, walks into a debriefing with Commander Frank Camparelli and Executive Officer, Commander "Cowboy" Parker. Camparelli tells Jake to put Morgan's death behind him and to write a letter to Sharon, Morg's wife. New pilot Jack Barlow, nicknamed "Razor" because of his youthful appearance, is then introduced.

Lieutenant Commander Virgil Cole arrives on board and reports to Camparelli, who later tells Jake's roommate Sammy Lundeen to take Jake, Bob "Boxman" Walkawitz and "Mad Jack" to fly into Subic Bay the next day and help Jake unwind. Jake goes to see Sharon, but she has already departed. He runs into a woman named Callie Troy, who is packing Sharon's things, and they have a small, tense encounter. After an altercation with civilian merchant sailors in the Tailhook Bar, Jake runs into Callie again. After they reconcile, dance and spend the night together, she reveals her husband was a Navy pilot himself and was killed on a solo mission over Vietnam.

Jake returns to the carrier, where Camparelli confronts him regarding the bar incident, and Cole reports in Jake's favor. Cole and Jake are paired on "Iron Hand" A-6Bs loaded with Standard and Shrike anti-radiation missiles for SAM suppression. During the mission, after a successful strike, they encounter and manage to evade a North Vietnamese MiG-17.

Jake suggests to Cole that they bomb Hanoi, which would be a violation of the restrictive rules of engagement (ROE) and could get them court-martialed. Cole initially rejects the idea. On the next raid, Boxman hits the suspected target, but is shot down by another SAM and killed. The North Vietnamese in Hanoi gloat on TV over the downing of U.S. aircraft. Cole then agrees with Jake's plan to attack Hanoi, deciding to hit "SAM City", a surface-to-air missile depot.

To secure their mission, they coercively enlist the aid of the Squadron Intelligence Officer, who has been caught urinating in the commander's coffee decanter, being the Phantom Shitter who's secretly repeated this deed throughout the first half of the film. He warns Jake and Cole that there's no chance of succeeding in their mission, but he is soundly ignored.

Sent to bomb a power plant in the vicinity of Hanoi, they drop two of their Mark 83 bombs, keeping eight for the missile depot and set a new course for Hanoi for their independent bombing mission. Arriving at SAM City, on their first pass, their armament computer malfunctions and they are forced to bomb 'by hand' (guesswork), and after barely surviving a barrage of enemy fire, their bombs fail to release. The two come back around, rerun the route, successfully drop their bombs and manage to obliterate the missile depot in a spectacular display of secondary explosions. Upon returning to the carrier, Camparelli angrily chastises the pair for their independent mission and informs them of their impending court martial at the U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay. During the preliminary hearing, Cole and Grafton are criticized for their actions, and informed that their naval careers are essentially over.

The charges are dropped the next day when Operation Linebacker II is ordered by President Richard M. Nixon, and the unauthorized mission is covered up. The next day, Camparelli grounds Jake and Cole while the rest of the carrier's A-6 and A-7 crews conduct a daylight raid to destroy anti-aircraft emplacements: the tangible, lucrative targets they've longed to attack. Camparelli is hit by a ZSU-23-4 Shilka AA tank and crash lands, his bombardier dead. Sammy Lundeen is hit and has to head for the ocean. Razor is ordered by Camparelli to disengage and obeys. Jake and Cole, defying orders, man their Intruder, launch and fly one more time to assist Camparelli. They destroy the ZSU, but are forced to eject from their heavily damaged aircraft. After bailing out, Jake lands near Camparelli's crashed Intruder and runs to cover with Camparelli. Separated from Jake, Cole is mortally wounded in hand-to-hand combat with an enemy soldier. On the radio, he lies to Jake, telling him he has already gotten away. Moments later, a pair of U.S. Air Force A-1 Skyraiders ("Sandy") appear and provide cover.

Cole instructs the lead Sandy to drop ordnance on the spot he has marked with smoke. He is killed along with a few dozen NVA soldiers. Cole's final voice transmission to Sandy is: "Alpha Mike Foxtrot"! (meaning "Adios, mother fucker!") Jake and Camparelli retreat into the woods, pursued by a sniper. A "Jolly Green Giant" helicopter picks up the two men, and the Skyraiders make one final napalm run to finish the job.

Later, recovering from his injuries, Jake joins his crew and Camparelli, all in their Navy whites, on deck to prepare for entry at a port of call. Jake and Camparelli reconcile their differences, and the movie ends in rolling credits.

Cast

[edit]- Danny Glover as Commander Frank "Dooke" Camparelli

- Willem Dafoe as Lieutenant Commander Virgil "Tiger" Cole

- Brad Johnson as Lieutenant Jake "Cool Hand" Grafton

- Rosanna Arquette as Callie Troy

- Tom Sizemore as Bob "Boxman" Walkawitz

- J. Kenneth Campbell as Lieutenant Commander "Cowboy" Parker

- Jared Chandler as Lieutenant Junior Grade Jack "Razor" Barlow

- Dann Florek as Lieutenant Commander Jack "Mad Jack" / "Doc"

- Madison Mason as C.A.G.

- Ving Rhames as Master Chief Petty Officer Frank McRae

- Christopher Rich as Lieutenant Morgan "Morg" McPherson

- Douglas Roberts as "Guffy"

- John Corbett as "Big Augie"

- Scott N. Stevens as Hardesty

- Justin Williams as Lieutenant Sammy Lundeen

- Politician and actor Fred Thompson has an uncredited role as a JAGC Captain during the court-martial sequence, reflecting his real-life profession as an attorney. David Schwimmer has a bit part as a Squadron Duty Officer. David Wilson, a military advisor to the production, appears as an officer in the flight briefing.

Production

[edit]Original novel

[edit]The US Naval Institute, which publishes Proceedings, the professional journal of the US Navy, had a success publishing the first original novel in its 112-year history with The Hunt for Red October. They were flooded with manuscripts and decided to publish as a follow-up Flight of the Intruder by Stephen Coonts.[2] Coonts was a Denver lawyer who had flown during the Vietnam War; he was discharged in 1977 after nine years of active duty, including two combat cruises aboard the Enterprise, 1600 hours in Intruders and 305 carrier landings, 100 of them at night. He had sent the book to 36 publishers, 30 of whom refused to look at it, four who rejected it and two that he was waiting to hear back from.[3] Coonts says he made up the central thrust of the film: "There was no secret bombing. It comes out of the character's deep-seated sense of frustration with the course of the war".[4]

The book became a best seller, due in part to an endorsement from Tom Clancy and President Ronald Reagan (who had liked Red October) and was a selection for the Book of the Month Club. Paperback rights were sold for $341,000.[5][6]

The book spent over six months on the best seller list and sold over 230,000 copies in hardback. Coonts signed a contract with Doubleday to write another novel about pilot Jake Grafton, Final Flight. The Naval Institute Arm sent Coonts a letter asking for a licensing fee to use the character again.[3]

Development

[edit]Film rights were bought by producer Mace Neufeld, who had filmed The Hunt for Red October. A script was written and John McTiernan was originally going to direct Intruder but dropped out and eventually served as an executive producer.[7] The Russian sequences in the film of October had been rewritten at Sean Connery's request by John Milius, and Milius was signed to direct Intruder.[8]

Milius commented about the novel: "It was such an internal examination of that life and what it takes to fly. There was such wonderful reality on life aboard a naval carrier and life in Vietnam. I loved the whole idea of what those guys do".[9]

Milius rewrote the original script. According to Sam Sayers, who worked on the film as technical adviser, "I never saw the first script, but I understand there were scenes of pilots smoking pot and that kind of nonsense. It was unrealistic - Top Gun in Vietnam. Milius just went back to the book. It's the reason he wanted to make the film".[4]

Coonts said that "most books don't seem to survive, but this was an excellent transition. It takes 12 hours to read the book on tape, and it's certainly abridged - 13 flights in the book are scrunched down to four, and the role of the girl (played by Rosanna Arquette) is smaller. But the themes of the film are the same as the book".[4]

Milius said that he was not interested in debating about the Vietnam War, but about "what happens to people, in this case the professionals who fought it, and their reactions as human beings, the institutions that people belong to and give themselves to that are larger than themselves... It certainly is no more patriotic than The Right Stuff, but it's in the same vein".[10]

Milius also added that "one of the things I like about the military, and why I'd have loved to be an officer in the Navy, is that the (moral) code is very simple. I come from a business where there's a preponderance of literature on the lack of morality - and I don't find it terribly entertaining, that atmosphere, in fact I find it rather weak".[10]

The lead roles of the pilots were given to Richard Gere and Brad Johnson; Johnson had just played a key role in Steven Spielberg's Always (1989). Milius talked to Richard Dreyfuss about playing the squadron commander.[11] Rosanna Arquette had the female lead. Gere dropped out and was replaced by Willem Dafoe. Danny Glover played the squadron commander. The film included an early role for Tom Sizemore.

Danny Glover spent five days aboard the aircraft carrier USS Independence for research, which he said made him appreciate the story more: "It's about the camaraderie and the bond of trust that exists between men under stress. The camaraderie and trust I've seen among the men here, many only 18 or 20 years old, in peacetime, has got to be that much stronger under conditions of conflict, especially if they don't feel they're supported from up above".[10]

Shooting

[edit]Filming began in November 1989 on location in Hawaii.

Flight of the Intruder was made with complete U.S. Navy cooperation, with eight Naval Air facilities at the disposal of the Paramount production team.[12] The USS Independence (CV-62), provided for two weeks of filming in November 1989 and A-6E Intruders from VA-165 "Boomers" were used. Members of VA-165 spent two weeks on the Independence. The film crew kept the ship's fire party busy with numerous small electrical fires started by their lighting equipment.[13] The Navy had script approval and was reimbursed for costs associated with the film: an estimated $1.2 million.[14][15]

The ship seen on guard station in the background as Grafton threw Morg's fuzzy dice overboard after his memorial service was the USS William H. Standley (CG-32). Naval Air Station Barbers Point Hawaii Hangar 111 (HSL-37 and VC-1 hangar) housed the A-6 Intruders during filming in Hawaii. The battleship USS Missouri along with USS Peleliu (LHA-5) can be seen behind Camparelli during the court martial sequence. USS Sides (FFG-14) also appears in a separate scene. Two scenes were shot at Naval Station Long Beach, California.

Future U.S. Senator Fred Thompson had a major speaking part during the court-martial sequence, portraying a U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps captain. As a favor to his friend, John Milius, Ed O'Neill was originally cast in the movie in a small uncredited role, but when the film was screened for test audiences, his appearance led to laughter, as audience members associated him with his Married... with Children character, Al Bundy. The director recast his character and reshot those scenes.[16]

Milius described the film as one of the "worst experiences" of his career:

That was Paramount with the Paramount control, and they tried to control every aspect of it. I'd spent more money than I'd ever spent before, because they told me how much I was going to spend on it. They didn't let me control it. I would have made that movie for at least $5 million less.[17][N 1]

Before the film was released, Milius did a draft of Clear and Present Danger.[19]

Aircraft used

[edit]Flight of the Intruder required early variants of the A-6 Intruder, the A-6A conventional bomber and A-6B equipped with specialized electronics and weapons for suppression of enemy air defenses missions. [N 2] All operational A-6s at the time of filming, however, had been updated to the A-6E without the TRAM targeting equipment, or KA-6D standards. The A-6 featured in the crash scene was a detailed mock-up patterned from an actual aircraft but with a foreshortened rear fuselage.[20] The large-scale (1/160) miniature of Hanoi and "Sam City" was recreated to serve as the backdrop for rear projection work.[21]

Other aircraft included a Sikorsky SH-3 "Sea King" rescue helicopter in various action sequences, with brief appearances of U.S. Navy aircraft such as the North American RA-5C Vigilante, Vought A-7 Corsair II, Grumman C-2 Greyhound and McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, as well as a MiG-17 in North Vietnamese markings. Two privately owned Douglas A-1 Skyraiders also flew in the rescue sequence.[12] [N 3]

Differences from the novel

[edit]In the novel, the A-6 Intruder pilots operate from the fictional aircraft carrier USS Shiloh. Grafton enlists his new bombardier Cole and Abe Steiger (the squadron intelligence officer) to attack the headquarters of the Communist Party in Hanoi, but Steiger is unable to find any information on Communist Party Headquarters among the targeting materials available aboard the Shiloh.[22] They ultimately decide to attack the National Assembly building as requesting targeting information about Communist Party Headquarters would raise unwanted attention and suspicion.[22] In the novel, Callie had not been previously wed (nor was she a mother). In another departure from the film, Grafton and Cole are shot down during a twilight SAM suppression raid. Major Frank Allen, an Air Force A-1 pilot and member of the rescue operation to recover Grafton and Cole, is shot down. Dying and unable to free himself from his aircraft, he calls in a strike on his location, not Cole. The novel ends with Cole and Grafton being rescued. Cole is eventually transferred to Naval Hospital Pensacola, Florida, for treatment of his wounds while Grafton reflects on his progress towards his naval service and gets lost in a state of limbo regarding his career.

Reception

[edit]The film was meant to be released on July 13, 1990, but was delayed in order to shoot a new ending.[23][24] Neufeld said the studio did not want the film to compete with two other military-aircraft themed films, Memphis Belle and Air America. Also he wanted to film an additional scene aboard the USS Ranger in San Diego with Danny Glover and Brad Johnson: "We worked around the navy's schedule. After all, you just don't put in an order for one of these things to come into port".[25] The film was eventually released in January 1991. It coincided with the beginning of Operation Desert Storm.[26]

Box office performance

[edit]The film earned $5,725,133 in its first weekend on 1,489 screens, making it the fourth most popular film in the US. Its final theater gross was $14,587,732, failing to recoup its $30 million budget.[27]

Critical response

[edit]Flight of the Intruder earned mostly negative reviews upon its release, with many reviewers noting inconsistencies in plot and continuity errors in the final edit, as well as the low-budget special effects. On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 25% approval rating based on 12 reviews, with a rating average of 4.80/10.[28] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale.[29]

Roger Ebert called the film a "mess", noting that "some scenes say one thing, some say another, while the movie develops an absurd and unbelievable ending and a final shot so cloying you want to shout rude suggestions at the screen".[30] In a 2019 interview, Stephen Coonts, the author of the book on which the film was based, gave two reasons for the poor quality of the film. Firstly, his book being poorly suited for adaption into a film, and secondly micromanagement from the US Navy, which was providing access to its ships and aircraft for the film.[31]

Video game

[edit]Flight of the Intruder, a video game based on the original novel, was released for personal computers in 1990 and re-released for the Nintendo Entertainment System around the same time as the film. Developed by Rowan Software, Ltd. and published by Spectrum Holobyte, the game allowed players the choice of flying either the Grumman A-6 Intruder or the F-4 from aircraft carriers against targets in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

In popular culture

[edit]The theme music of Flight of the Intruder was later used as the opening theme of the Belgian TV humorous talk show/game show series Schalkse Ruiters.[32][33]

Notes

[edit]- ^ John Milius rewrote the script but was unable to obtain screen credit.[18]

- ^ The US Navy called suppression of enemy air defenses "Iron Hand" missions and the US Air Force called them "Wild Weasel" missions.

- ^ The Shilka anti-aircraft vehicle seen at the final scenes was not used in the Vietnam War, since its first combat use was during the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

References

[edit]- ^ Cerone, Daniel (3 Jan 1991). "Voyage to the Next Dimension: With the visual effects process Introvision; film makers can transport actors to settings limited only by the imagination". Los Angeles Times. p. F3.

- ^ McDowell, Edwin (19 May 1986). "Publishing: Waldheim's Memoirs". New York Times. p. C22.

- ^ a b Streitfeld, David (18 March 1988). "Character Controversy: Naval Press in Conflict With a Second Author Naval Institute Press". The Washington Post. p. D1.

- ^ a b c Hart, John (17 January 1991). "Vietnam War Film Has Timely Debut 'Flight Of The Intruder' Release Was Postponed Last Summer". Seattle Times.

- ^ Monaghan, Charles (28 September 1986). "A Cop Who Writes". The Washington Post. p. BW15.

- ^ McDowell, Edwin (1 November 1986). "New Best-Selling Novel At Naval Institute Press". New York Times. p. 9.

- ^ Broeske, Pat (1 March 1990). "Will History Sink 'Red October'?: Movies: Hollywood wonders if glasnost-era audiences will care about Tom Clancy's quintessential Cold War saga of a renegade Soviet sub commander". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Sharbutt, Jay (16 July 1989). "'Red October' Surfaces: Tom Clancy's thriller arrives -- with Connery, U.S. aid and emigres". Los Angeles Times. p. 307.

- ^ Chan, Sau (1 May 1995). "Author Review". The Free Lance-Star.

- ^ a b c Chase, Donald (2 Feb 1990). "There's no life like it when the cameras roll, Navy-style The cast and crew of Hollywood's Flight of the Intruder found a different world aboard a working aircraft carrier". The Globe and Mail. p. C.3.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (6 Aug 1989). "Cinefile". Los Angeles Times. p. 37.

- ^ a b Farmer 1990, p. 62.

- ^ Farmer 1990, p. 70.

- ^ Brass, Kevin. "Intruders Welcome on the Set: Filmmaking: Director John Milius says the Navy, which had full script approval, was more of a help than a hindrance in 'Flight of the Intruder'". LA Times, January 22, 1991. Retrieved: May 1, 2013.

- ^ Cerone, Daniel (27 May 1990). "GOING FOR ACTION!". Los Angeles Times. p. SB36A.

- ^ Broeske, Pat H. "Outtakes: No Laughing Matter." LA Times, September 16, 1990. Retrieved: May 2, 2013.

- ^ Plume, Ken. "Interview with John Millius." IGN Film, May 7, 2003. Retrieved: January 5, 2013.

- ^ Segaloff 2006, p. 306.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (27 Apr 1990). "A whole lineup for the producer of 'Hunt for Red October' An Oscar candidate is to open the Israel Film Festival at the Biograph". New York Times. p. C12.

- ^ Farmer 1990, p. 36.

- ^ Farmer 1990, p. 66.

- ^ a b Coonts, S (1986). Flight of the Intruder. Pocket Books. p. 279.

- ^ Broeske, Pat H. "Flight to Whenever"; Outtakes." Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1990. Retrieved: May 2, 2013.

- ^ "O'Malley & Collin INC". Chicago Tribune. 11 June 1990. p. D14.

- ^ Broeske, Pat H. (29 July 1990). "Flight to Whenever". Los Angeles Times. p. F22.

- ^ "War Film May Hit Too Close to Home to Be a Hit: Entertainment: A movie about Navy fliers who strike a hostile city may benefit from current events or turn off audiences". Los Angeles Times. 19 Jan 1991. p. D2.

- ^ "'Home Alone' Fends Off Yet Another 'Intruder': Box Office: Vietnam War film opens to mediocre business as comedy remains on top for 10th week. After four weeks of release, 'Godfather Part III' drops to 12th." Los Angeles Times, January 22, 1991. Retrieved: June 3, 2012.

- ^ Flight of the Intruder, Rotten Tomatoes, retrieved 2022-03-20

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 18, 1991). "Flight Of The Intruder movie review (1991)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Aiello, Vincent (2019) The Fighter Pilot Podcast, A-6 Intruder, Ep. 47

- ^ The Flight of the Intruder - Schalkse Ruiters. "The Flight of the Intruder - Schalkse Ruiters | Band Press". 2017.bandpress.be. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "Lang leve 60 jaar TV-tunes : Canvas - Muziekweb". Muziekweb.nl. 1959-11-30. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

Bibliography

[edit]- Farmer, James H. "Making 'Flight of the Intruder'". Air Classics, Volume 26, No. 8, August 1990.

- Segaloff, Nat. "John Milius: The Good Fights". McGilligan, Patrick. Backstory 4: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1970s and 1980s. Berkeley, California: University of California, 2006. ISBN 9780520245181.