Genre painting (or petit genre), a form of genre art, depicts aspects of everyday life by portraying ordinary people engaged in common activities.[1] One common definition of a genre scene is that it shows figures to whom no identity can be attached either individually or collectively, thus distinguishing it from history paintings (also called grand genre) and portraits. A work would often be considered as a genre work even if it could be shown that the artist had used a known person—a member of his family, say—as a model. In this case it would depend on whether the work was likely to have been intended by the artist to be perceived as a portrait—sometimes a subjective question. The depictions can be realistic, imagined, or romanticized by the artist. Because of their familiar and frequently sentimental subject matter, genre paintings have often proven popular with the bourgeoisie, or middle class.

Genre subjects appear in many traditions of art. Painted decorations in ancient Egyptian tombs often depict banquets, recreation, and agrarian scenes, and Peiraikos is mentioned by Pliny the Elder as a Hellenistic panel painter of "low" subjects, such as survive in mosaic versions and provincial wall-paintings at Pompeii: "barbers' shops, cobblers' stalls, asses, eatables and similar subjects".[2] Medieval illuminated manuscripts often illustrated scenes of everyday peasant life, especially in the Labours of the Months in the calendar section of books of hours, most famously the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

To 1800

[edit]The Low Countries dominated the field until the 18th century, and in the 17th century both Flemish Baroque painting and Dutch Golden Age painting produced numerous specialists who mostly painted genre scenes.

In the previous century, the Flemish Renaissance painter Jan Sanders van Hemessen painted innovative large-scale genre scenes, sometimes including a moral theme or a religious scene in the background in the first half of the 16th century. These were part of a pattern of "Mannerist inversion" in Antwerp painting, giving "low" elements previously in the decorative background of images prominent emphasis. In the second half of the 16th century, Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer painted in Antwerp works showing in the foreground cooks or market-sellers amidst a bountiful spread of vegetables, fruit and/or meat, with small religious scenes in spaces in the background. Around the same time, Pieter Brueghel the Elder made peasants and their activities, very naturalistically treated, the subject of many of his paintings.

Adriaen and Isaac van Ostade, Jan Steen, Adriaen Brouwer, David Teniers, Joos van Craesbeeck, Gillis van Tilborgh, Aelbert Cuyp, Willem van Herp, David Ryckaert III. Jacob Jordaens, Johannes Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch were among the many painters specializing in genre subjects in the Low Countries during the 17th century. The generally small scale of these artists' paintings was appropriate for their display in the homes of middle class purchasers.

The apparent 'realism' of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art gives the viewer the initial impression that the artist solely intends to depict scenes of common life in a realistic way. Underneath the realistic representation are, however, often hidden underlying meanings, either moral or symbolic. For instance, Gabriel Metsu's The Poultry seller, 1662 shows an old poultry seller handing a young woman a live rooster with its head craning upwards. The suggestive pose of the rooster's head and the fact that the Dutch word for 'birds' (vogelen) was also a vulgar term for sexual intercourse indicated that the artist also included a scabrous meaning in his painting.[3] Genre painters often included symbolic meanings in their paintings. For instance, Adriaen Brouwer painted a number of genre portraits that represent the five senses or the seven deadly sins. An example is his genre group portrait The Smokers which depicts the sense of taste.[4] Other artists included moral meanings into their genre scenes. Jan Steen's The Happy Family painted in 1668 depicts a merry family evening with the head of the family, clearly inebriated, singing out his lungs, backed up by the mother and grandmother. The children join in on musical instruments. The moral of the picture is clarified in the note hanging from the mantelpiece reading "So de ouden songen, so pijpen de jongen" ("As the Old Sing, So the Young Pipe"), i.e. children will learn their behaviour from their parents.[5] Jacob Jordaens had painted a series of paintings on the same subject matter about 30 years earlier.[6]

One of the recurring themes in Flemish and Dutch genre painting is that of the merry company. These works typically show a group of figures at a party, whether making music at home or just drinking in a tavern. Other common types of scenes showed markets or fairs, village festivities ("kermesse"), or soldiers in their camp or guardroom.

The Dutch painter Pieter van Laer arrived in 1625 in Rome where he started to paint genre paintings incorporating scenes of the Roman Campagna. He also joined a loose organisation of Flemish and Dutch painters in Rome known as the Bentvueghels (Dutch for 'birds of a feather'). Van Laer was given the nickname "Il Bamboccio", which means "ugly doll" or "puppet". A number of Flemish and Dutch and later also Italian painters, who painted genre scenes of the Roman countryside inspired by van Laer's works were subsequently referred to as the Bamboccianti. The initial Bamboccianti included Andries and Jan Both, Karel Dujardin, Jan Miel and Johannes Lingelbach. Sébastien Bourdon was also associated with this group during his early career.[7] Other Bamboccianti include Michiel Sweerts, Thomas Wijck, Dirck Helmbreker, Jan Asselyn, Anton Goubau, Willem Reuter, and Jacob van Staverden.[8] Their whose works would inspire local artists Michelangelo Cerquozzi, Giacomo Ceruti, Antonio Cifrondi, and Giuseppe Maria Crespi among many others.

Louis le Nain was an important exponent of genre painting in 17th-century France, painting groups of peasants at home, where the 18th century would bring a heightened interest in the depiction of everyday life, whether through the romanticized paintings of Watteau and Fragonard, or the careful realism of Chardin. Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805) and others painted detailed and rather sentimental groups or individual portraits of peasants that were to be influential on 19th-century painting.

In England, William Hogarth (1697–1764) conveyed comedy, social criticism and moral lessons through canvases that told stories of ordinary people ful of narrative detail (aided by long sub-titles), often in serial form, as in his A Rake's Progress, first painted in 1732–33, then engraved and published in print form in 1735.

Developments in 16th Netherlandish art were received in Spain through the presence of Flemish artists working on projects in Spain as well as through Spain's sovereignty over the Spanish Netherlands. During the Spanish Golden Age of painting in the 17th century, many picaresque genre scenes of street life as well as the kitchen scenes known as bodegones were painted by Spanish artists such as Velázquez (1599–1660) and Murillo (1617–82). More than a century later, the artist Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) used genre scenes in painting and printmaking as a medium for dark commentary on the human condition. Beginning in about 1808 Goya painted a significant number of genre scenes and he dealt with genre subjects again in various drawings during the period from 1810 to 1823.[9]

19th century

[edit]

With the decline of religious and historical painting in the 19th century, artists increasingly found their subject matter in the life around them. Realists such as Gustave Courbet (1819–77) upset expectations by depicting everyday scenes in large canvases of a scale traditionally reserved for "important" subjects. They thus blurred the boundary which had set genre painting apart as a "minor" category. Realist paintings on such a scale, and the new type showing people at work, emphasizing the effort involved, would not normally be called "genre paintings". Both monumental scale and the depiction of exhausting work are exemplified by Barge Haulers on the Volga (Ilya Repin, 1873). History painting itself shifted from the exclusive depiction of events of great public importance to the depiction of genre scenes in historical times, both the private moments of great figures, and the everyday life of ordinary people. In French art this was known as the Troubador style. This trend, already apparent by 1817 when Ingres painted Henri IV Playing with His Children, culminated in the pompier art of French academicians such as Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) and Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (1815–91). In the second half of the century interest in genre scenes, often in historical settings or with pointed social or moral comment, greatly increased across Europe.

William Powell Frith (1819–1909) was perhaps the most famous English genre painter of the Victorian era, painting large and extremely crowded scenes; the expansion in size and ambition in 19th-century genre painting was a common trend. Other 19th-century English genre painters include Augustus Leopold Egg, Frederick Daniel Hardy, George Elgar Hicks, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais. Scotland produced two influential genre painters, David Allan (1744–96) and Sir David Wilkie (1785–1841). Wilkie's The Cottar's Saturday Night (1837) inspired a major work by the French painter Gustave Courbet, After Dinner at Ornans (1849). Famous Russian realist painters like Vasily Perov and Ilya Repin also produced genre paintings.

In Germany, Carl Spitzweg (1808–85) specialized in gently humorous genre scenes, and in Italy Gerolamo Induno (1825–90) painted scenes of military life. Subsequently, the Impressionists, as well as such 20th-century artists as Pierre Bonnard, Itshak Holtz, Edward Hopper, and David Park painted scenes of daily life. But in the context of modern art the term "genre painting" has come to be associated mainly with painting of an especially anecdotal or sentimental nature, painted in a traditionally realistic technique.

In Belgium, the nationalism of the new state born in 1830 gave rise to history painting glorifying the past of the nation and genre painting returning to the models of 17th-century. Examples of artists working in this retro style include Ferdinand de Braekeleer, Willem Linnig the Elder and Jan August Hendrik Leys. Under the influence of foreign artistic movements such a realism, Belgian artists in the second half of the 19th century were able to break away from the old traditions and create a new format for their genre paintings. An example is Henri de Braekeleer who used light and colour to infuse his intimist genre scenes with a modernist spirit.[10]

The first true genre painter in the United States was the German immigrant John Lewis Krimmel. He was influenced, at least initially, by English artists such as William Hogarth and Scottish painters such as David Wilkie and produced lively and gently humorous scenes of life in Philadelphia from 1812 to 1821.[11] Other notable 19th-century genre painters from the United States include George Caleb Bingham, William Sidney Mount, and Eastman Johnson. Harry Roseland focused on scenes of poor African Americans in the post-American Civil War South, and John Rogers (1829–1904) was a sculptor whose small genre works, mass-produced in cast plaster, were immensely popular in America.[12] The works of American painter Ernie Barnes (1938–2009) and those of illustrator Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) exemplify a more modern type of genre painting.[13]

Genre in Asian traditions

[edit]Japanese ukiyo-e prints are rich in depictions of people at leisure and at work, as are Korean paintings, particularly those created in the 18th century. Notable Korean painters include Kim Hongdo, Sin Yun-bok, and Kim Deuk-sin; notable Japanese printmakers include Katsushika Hokusai, Tōshūsai Sharaku, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Kitagawa Utamaro.

-

Kim Hong-do, Seodang, 1800s

-

Sin Yun-bok, Dano-pungjeong, 1800s

-

Kim Deuk-sin, Pajeokdo, 17000s

Gallery of Flemish genre paintings

[edit]-

Jan Sanders van Hemessen, Brothel scene, c. 1545–50

-

David Teniers the Younger, Tavern scene, 1640

-

Joos van Craesbeeck, Soldiers and Women, 1640s

-

Gillis van Tilborgh, Elegant Company, between 1655 and 1675

Gallery of Dutch 17th-century genre paintings

[edit]-

Hendrick Avercamp painted almost exclusively winter scenes.

-

Gerard van Honthorst, Merry Company, 1623, using the chiaroscuro technique typical of Utrecht Caravaggism

-

Judith Leyster, A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel, c. 1635

-

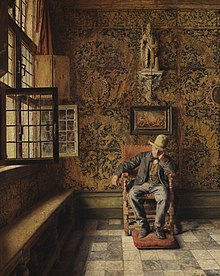

Pieter de Hooch, The Visit, c. 1657

References

[edit]- ^ Art & Architecture Thesaurus, s.v. "genre" Archived 2018-07-31 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 30 April 2022.

- ^ Book XXXV.112 of Natural History.

- ^ "E. de Jongh, 'Erotica in vogelperspectief. De dubbelzinnigheid van een reeks zeventiende-eeuwse genrevoorstellingen'· dbnl". DBNL. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Ingrid A. Cartwright, Hoe schilder hoe wilder: Dissolute Self-Por traiture in Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Art, Advisors: Wheelock, Arthur, PhD, 2007 Dissertation, University of Maryland University of Maryland (College Park, Md.), p. 8

- ^ H. Perry Chapman, Wouter Th. Kloek & Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. (1996) Jan Steen. Schilder en verteller, p. 172

- ^ Jan Steen, As the Old Sing, So the Young Pipe Archived 2021-11-08 at the Wayback Machine at the Mauritshuis

- ^ Brigstocke, Hugh. "Bourdon, Sébastien", Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 30 April 2022

- ^ Slive, Seymour (1995). "Italianate and Classical Painting". Pelican History of Art, Dutch Painting 1600–1800. Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 225–245

- ^ Francisco Goya Archived 2022-09-18 at the Wayback Machine at the National Gallery of Art

- ^ Jan Dirk Baetens, Review of: 'Henri De Braekeleer: 1840–1888' (2019) Archived 2020-11-23 at the Wayback Machine in Oud Holland, April 2020

- ^ Anneliese Harding, British and Scottish Models for the American Genre Paintings of John Lewis Krimmel, Winterthur Portfolio, Volume 38, Number 4 Winter 2003

- ^ Harry Roseland Archived 2022-05-21 at the Wayback Machine at Encore Editions

- ^ American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910 Archived 2022-09-27 at the Wayback Machine at the Metropoliton Museum

Further reading

[edit]- Buijsen, Edwin. "From 'Peasant Stories' to 'Urbane or Elegant Modern': A Birds-Eye View of Genre Painting in the Mauritshuis" In Van S Genre Paintings in the Mauritshuis, pp. 10–25.

- Van Suchtelen, Ariadne and Quentin Buvelot. Genre Paintings in the Mauritshuis. Zwolle: Waanders Publishers 2016.ISBN 978-94-6262-0940

See also

[edit]External links

[edit] Media related to genre paintings at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to genre paintings at Wikimedia Commons