There was widespread belief in ghosts in Polynesian culture, some of which persists today. After death, a person's ghost would normally travel to the sky world or the underworld, but some could stay on earth. In many Polynesian legends, ghosts were often involved in the affairs of the living. Ghosts might also cause sickness or even invade the body of ordinary people, to be driven out through strong medicines.[1]

Ghost spirit

[edit]In the reconstructed Proto-Polynesian language, the word "*qaitu"[2] refers to a ghost, the spirit of a dead person, while the word "*tupuqa" has a broader meaning including all supernatural beings.[3] Some of the ancient Māui legends that are common throughout the Polynesian islands include the idea of a double soul inhabiting the body. One was the soul which never forsakes man, and the other the soul that could be separated or charmed away from the body by incantations was the "hau".[4]

In some societies, the tattoo marks on the Polynesian's face indicated their cult. A spiral symbol meant that the man favoured the sky world, but before ascending there on a whirlwind his ghost had to travel to his people's homeland, situated in the navel of the world. Different markings indicated that the ghost chose to live in the underworld.[5] The Hawaiians believed in "aumakua", ghosts who did not go down into Po, the land of King Milu. These ghosts remained in the land of the living, guarding their former families.[6]

In Polynesian culture, it is believed that humans can not see the souls that have already crossed over into the other world, though it was believed that some extraordinary individuals with certain abilities could see them. However, the souls that do not cross over are left in the real world with their original appearance. Humans are able to see these roaming spirits mostly at night and sometimes during the day.[7] Ghosts of the dead usually will wander along the beach between sunset and sunrise.[8] These spirits would wander because they did not have proper ceremonies or that demons had harmed them and thrown them off their path in order to cross over to the other world. Over time, these wandering spirits would eventually become evil demons and would usually wander around significant locations, such as a birth place or where they had died, and wait for their chance to harm an innocent living soul.[7] These certain spirits can also be exorcised by name. [8] The underworld was considered to be the place where the souls of common people went. Polynesians viewed the underworld as a realm of dusk, shadows, and a barren wasteland without water, grass, flowers or trees.[7] Spirits who had entered the underworld were invisible but those who remained on earth for one reason or another could appear to mortals.[9]

Legends

[edit]All Polynesian societies have many stories of ghosts or spirits who played a role in their traditional legends. William Drake Westervelt collected and published eighteen of them in Hawaiian Legends of Ghosts and Ghost-Gods (1915).[10] The legend of Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanic fire, relates how she fell in love with a man, but found that he had died. She found his ghost as a thin presence in a cave, and with great difficulty used her magical powers to restore him to life. He was destroyed again, but his ghost was again found, this time in the form of a bird flitting over the waters, and was once more restored to life.[11]

Tinirau, the fish god or "innumerable" was the sea God with two faces known all throughout Polynesia.[12] He has been depicted in paintings as well as stone carvings from Samoa to Hawaii and has many back stories depending on where you are and who you ask. The Mangaia people of the Cook Islands portray him as half man and half fish.[13] Other cultures define him as a chief or the son of a chief. He is said to have promised endless amounts of fish to the islands, and many Hawaiians still pray to him for good fortune while fishing.[14] Pele the goddess of lava and volcanos has long been a part of the Hawaiian culture and is believed to be able to bring misfortune to natives and visitors alike. Pele is considered the creator of the islands and the embodiment of anger and jealousy.[15] Native Hawaiians know her by her more traditional name Halemaumau, which translates to "the fiery pit creator".[16] However, over time the legend has changed. Originally it was believed that if the rocks or ground was disturbed on the volcano that Pele would cause an eruption as a sign of being displeased.[17] In more recent years it is widely believed that if tourists take pieces of the rock or black sand off the islands with them that Pele will curse them and cause great misfortune in their lives until it is returned to where it came from. This belief causes hundreds of people a year to ship packages containing the stones they picked up while on vacation and blaming the goddess for bad things that happened to them since they returned home.[18]

Another Hawaiian legend tells of a young man who fell into the hands of the priests of a high temple who captured and sacrificed him to their god, and then planned to treat his bones dishonorably. The young man's ghost revealed the situation to his father through a dream, and aided his father to retrieve the bones through great exertions and to place them in his own secret burial cave. The ghost of the young man was then able to joyfully go down to the spirit world.[19]

Influence of ghosts

[edit]Ghost sickness in Polynesia takes two forms: possession and bizarre behavior, where the victim often talks with the voice of a dead person, and retarded healing caused by a ghost or evil spirit. The patient is treated with strong-smelling plants such as beach pea, island rue or ti plant (Cordyline fruticosa), and in the case of possession through reasoning with the ghost.[20] That this illness can be caused by sorcery and cured by mystical means seems to have been a common Polynesian belief. The Samoans thought that the souls of the dead could return to the land of the living by night and cause disease and death by entering the bodies of either their friends or their enemies. To cure illness, the Samoans relied not on medicine but exorcism. [21] The Polynesian people usually did not fear these spirits, unless they were deceased enemies of the individual or members of a tribe that had done them harm.[7] The Calypso, a ghost type that the Polynesians commonly refer to as, draw men who are at sea towards this specific island with their wives.[22] When they arrive, the man immediately gets home sick and the two head home. All the ghosts want to do is protect their homeland where their families once were, resulting in scaring people off who try to cross their boundaries.[23]

In the arts

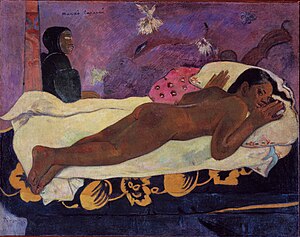

[edit]Of his 1892 Tahitian painting Manao Tupapau, Paul Gauguin said "according to Tahitian beliefs, the title Manao Tupapau has a double meaning . . . either she thinks of the ghost or the ghost thinks of her".[24]

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote about Polynesian beliefs and customs, including the belief in ghosts, in his last collection of stories, Island Nights' Entertainments. He wrote the book on Samoa in 1893 in a realistic style that was not well received by the critics, but the stories which dealt with false and real supernatural events are now considered among his best.[25][26]

Robert Louis Stevenson was also a travel writer and he was previously mentioned in this section already. He wrote many books over his voyages which in themselves are art.[27] Art helps the reader grasp a concept from the time period it is about. The book "In the South Seas" was a descriptive piece to show what it is like traveling those areas including Polynesia

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ William Drake Westervelt (1985). Hawaiian Legends of Ghosts and Ghost-Gods. Forgotten Books. ISBN 1-60506-964-7.

- ^ *q in reconstructed Proto-Polynesian words indicates a glottal stop.

- ^ Patrick Vinton Kirch, Roger Curtis Green (2001). Hawaiki, ancestral Polynesia: an essay in historical anthropology. Cambridge University Press. p. 240. ISBN 0-521-78879-X.

- ^ W. D. Westervelt (1910). Legends of Maui, A Demi-God of Polynesia.

- ^ Donald A. MacKenzie (2003). Migration of Symbols. Kessinger Publishing. p. xvi. ISBN 0-7661-4638-3.

- ^ "Aumakuas, Or Ancestor-Ghosts". Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ a b c d Bucková, Martina. "A COMPARISON AND ANALYSIS OF ESCHATOLOGICAL THEMES IN POLYNESIAN MYTHOLOGY AS A SURVIVOR OF PROTO-POLYNESIAN UNITY." Asian & African Studies (13351257) 20.1 (2011). https://www.sav.sk/journals/uploads/091911126_Buckov%c3%a1.pdf

- ^ a b Kirtley, Bacil F. (2019-09-30). A Motif-Index of Traditional Polynesian Narratives. University of Hawaii Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvp2n3hb. ISBN 978-0-8248-8407-9.

- ^ Schrempp, Gregory; Craig, Robert D. (1991). "Dictionary of Polynesian Mythology". The Journal of American Folklore. 104 (412): 231. doi:10.2307/541247. ISSN 0021-8715. JSTOR 541247.

- ^ Robert D. Craig (2004). Handbook of Polynesian mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 112. ISBN 1-57607-894-9.

- ^ "Pe-le, Hawaii's Goddess Of Volcanic Fire". Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ Hammond, Joyce D. (1995), "The Tourist Folklore of Pele", Out Of The Ordinary, Utah State University Press, pp. 159–179, doi:10.2307/j.ctt46nwn8.16, ISBN 9780874213201

- ^ Hammond, Joyce D. (1995), "The Tourist Folklore of Pele", Out Of The Ordinary, Utah State University Press, pp. 159–179, doi:10.2307/j.ctt46nwn8.16, ISBN 9780874213201

- ^ Hammond, Joyce D. (1995), "The Tourist Folklore of Pele", Out Of The Ordinary, Utah State University Press, pp. 159–179, doi:10.2307/j.ctt46nwn8.16, ISBN 9780874213201

- ^ Bray, Carolyn H. (2016-04-02). "Pele's Search for Home: Images of the Feminine Self". Jung Journal. 10 (2): 10–23. doi:10.1080/19342039.2016.1158580. ISSN 1934-2039. S2CID 171307315.

- ^ Gorrell, Michael Gorrell (2011). "E-books on EBSCOhost: Combining NetLibrary E-books with the EBSCOhost Platform". Information Standards Quarterly. 23 (2): 31. doi:10.3789/isqv23n2.2011.07. ISSN 1041-0031.

- ^ Hammond, Joyce D. (1995). "The Tourist Folklore of Pele:: Encounters with the Other". In Walker, Barbara (ed.). Out Of The Ordinary: Folklore and the Supernatural. University Press of Colorado. pp. 159–179. doi:10.2307/j.ctt46nwn8.16. ISBN 9780874211917. JSTOR j.ctt46nwn8.16.

- ^ Walker, Barbara, ed. (1995-10-01). Out Of The Ordinary: Folklore and the Supernatural. Utah State University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt46nwn8.16. ISBN 9780874213201. JSTOR j.ctt46nwn8.

- ^ "The Ghost Of Wahaula Temple". Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ "Polynesian Herbal Medicine" (PDF). University of Hawai'i. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 2, 2006. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ Lewis, Robert E. "The Soul and the Afterworld in hawaiian Myth and in Other Polynesian Cultures." (1980). https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/21180/Lewis_1980.pdf

- ^ Beckwith, Martha (1944). "Polynesian Story Composition". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 53 (4): 177–203. ISSN 0032-4000. JSTOR 20702987.

- ^ "Aumakuas, or Ancestor-Ghosts". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ^ Lee Wallace. "Tropical Rearwindow: Gauguin's Manao Tupapau and Primitivist Ambivalence". Genders 28 1998. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ Island Nights' Entertainments. Charles Scribner. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ Stephen Arata (2006). The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. Vol. 5: 99-102: Robert Louis Stevenson.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2020-12-02.