| Part of a series on |

| New Testament apocrypha |

|---|

|

|

|

The Gospel of Marcion, called by its adherents the Gospel of the Lord, or more commonly the Gospel, was a text used by the mid-2nd-century Christian teacher Marcion of Sinope to the exclusion of the other gospels. The majority of scholars agree that this gospel was a later revised version of the Gospel of Luke,[2] though several involved arguments for Marcion priority have been put forward in recent years.[3][4][5][6][7]

There are debates as to whether several verses of Marcion's gospel are attested firsthand in a manuscript in Papyrus 69, a hypothesis proposed by Claire Clivaz and put into practice by Jason BeDuhn.[1][3] Thorough, meticulous, yet highly divergent reconstructions of much or all of the content of the Gospel of Marcion have been made by several scholars, including August Hahn (1832),[8] Theodor Zahn (1892), Adolf von Harnack (1921),[9] Kenji Tsutsui (1992), Jason BeDuhn (2013),[3] Dieter T. Roth (2015),[10] Matthias Klinghardt (2015/2020, 2021),[4] and Andrea Nicolotti (2019).[7]

Contents

[edit]Reconstructions of the text of Marcion's Gospel make careful use of second-hand quotations and paraphrases to the text as found in anti-Marcionite writings by orthodox Christian apologists, especially Tertullian, Epiphanius, the Dialogue of Adamantius. Of these secondary witnesses, Tertullian contributes the most material and references, Epiphanius the second most, and the Dialogue of Adamantius the third most.[11]

Like the Gospel of Mark, Marcion's gospel lacked any nativity story. Luke's account of the baptism of Jesus was also absent. The gospel began, roughly, as follows:

In the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, Jesus descended into Capernaum, a city in Galilee, and was teaching on the Sabbath days.[12][13] (cf. Luke 3:1a, 4:31)

Other Lukan passages that did not appear in Marcion's gospel include the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son.[14]: 170

While Marcion preached that the God who had sent Jesus Christ was an entirely new, alien god, distinct from the vengeful God of Israel who had created the world,[15]: 2 this view was not explicitly taught in Marcion's gospel.[14]: 169 The Gospel of Marcion is, however, much more amenable to a Marcionite interpretation than the canonical Gospel of Luke, because it lacks many of the passages in Luke that explicitly link Jesus with Judaism, such as the parallel birth narratives of John the Baptist and Jesus in Luke 1-2.[citation needed]

Three hypotheses on the gospels of Marcion and Luke

[edit]There are three main hypotheses concerning the relationship between the gospel of Marcion and the gospel of Luke:[16]

1. Marcion's Evangelion derives from Luke by a process of reduction (The Patristic Hypothesis).

2. Luke derives from Marcion's Evangelion by a process of expansion (The Schwegler Hypothesis).

3. Marcion's Evangelion and Luke are both independent developments of a common proto-gospel (The Semler Hypothesis).

Patristic hypothesis

[edit]The proto-orthodox and orthodox Church Fathers maintained that Marcion edited Luke to fit his own theology, Marcionism, and modern scholars such as Metzger, Ehrman, and Roth have maintained this as well.[17][18] The late 2nd-century writer Tertullian stated that Marcion, "expunged [from the Gospel of Luke] all the things that oppose his view... but retained those things that accord with his opinion".[19]

According to this view, Marcion eliminated the first two chapters of Luke concerning the nativity, and began his gospel at Capernaum making modifications to the remainder suitable to Marcionism. The differences in the texts below are interpreted by advocates of this hypothesis as evidence of Marcion editing Luke to omit the Hebrew Prophets and to better support a dualistic view of the earth as evil.

| Luke | Marcion's Gospel |

|---|---|

| O foolish and slow of heart to believe in all that the prophets have spoken (24:25) | O foolish and hard of heart to believe in all that I have told you (24:25) |

| They began to accuse him, saying, 'We found this man perverting our nation' (23:2) | They began to accuse him, saying, 'We found this man perverting our nation [...] and destroying the law and the prophets.' (23:2) |

| I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth (10:21) | I thank you, heavenly Father... (10:21) |

Late 19th- and early 20th-century theologian Adolf von Harnack, in agreement with the traditional account of Marcion as revisionist, theorized that Marcion believed there could be only one true gospel, all others being fabrications by pro-Jewish elements, determined to sustain worship of Yahweh; and that the true gospel was given directly to Paul the Apostle by Christ himself, but was later corrupted by those same elements who also corrupted the Pauline epistles. In this understanding, Marcion saw the attribution of this gospel to Luke the Evangelist as a fabrication, so he began what he saw as a restoration of the original gospel as given to Paul.[20] Harnack wrote that:

For this task he did not appeal to a divine revelation, any special instruction, nor to a pneumatic assistance [...] From this it immediately follows that for his purifications of the text – and this is usually overlooked – he neither could claim nor did claim absolute certainty.[20]

Semler hypothesis and Schwegler hypothesis

[edit]A "long line of scholars" have rejected the traditional view that the Gospel of Marcion was a revision of the Gospel of Luke, and instead argued that it reflects an early version of Luke later expanded into its canonical form.[21] These scholars see a consistent pattern running in the opposite direction, that Marcion's Gospel usually attests simpler, earlier textual traditions than corresponding content in canonical Luke both at the micro- and macro-level. The following examples (all attested by Greek witnesses to the Gospel of Marcion) illustrate this point of view.

| Canonical Luke | Marcion's Gospel |

|---|---|

| Rejoice in that day and leap for joy, for surely your reward is great in heaven; for that is what their fathers did to the prophets. (6:23) | Your fathers have done the same already to the prophets. (6:23)[4]: 1288 |

| O faithless and perverse generation, how long will I be with you and endure you? (9:41) | Faithless generation! How long must I put up with you? (9:41)[4] |

| That slave who knew what his master wanted, but did not prepare himself or do what was wanted, will receive a severe beating. (12:47) | For the slave who knew yet did not act will be flogged many times (12:47)[22] |

Scholars who reject the Patristic hypothesis defend either of the two hypotheses. One group argues that both gospels are independent redactions of a "proto-Luke", with Marcion's text being closer to the original proto-Luke. This position is called the Semler hypothesis after the name of its creator, Johann Salomo Semler. This position has been supported by scholars such as Josias F.C. Loeffler,[23] Johann E.C. Schmidt,[24] Leonhard Bertholdt,[25] Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, John Knox,[15]: 110 Karl Reinhold Köstlin, Joseph B. Tyson,[26] and Jason BeDuhn.[21][27] The other group argues that the Gospel of Luke is a later redaction of the Gospel of Marcion that significantly revised and expanded it. This position is called the Schwegler hypothesis after its creator Albert Schwegler.[28] This position has been supported by scholars such as Albrecht Ritschl,[29] Ferdinand Christian Baur,[30] Paul-Louis Couchoud, Georges Ory, John Townsend, R. Joseph Hoffman,[31] Matthias Klinghardt,[21] Markus Vinzent,[32][33][34] and David Trobisch.[35]

Several arguments have been put forward in favor of those two latter views.

Firstly, there are many passages found in reconstructions of Marcion's gospel (based on comments of his detractors) that seem to contradict Marcion's own theology, which would be unexpected if Marcion was simply removing passages from Luke with which he did not agree. Matthias Klinghardt (in 2008)[36] and Jason BeDuhn (in 2012)[37] have both made this argument in detail.

Secondly, Marcion is attested to have claimed that the gospel he used was original and that the canonical Luke was a falsification.[38]: 8 The accusations of alteration are therefore mutual.

Thirdly, John Knox[15] and Joseph Tyson[39] (both using Harnack's edition), and more recently Daniel A. Smith[40] (using Roth's edition), have all put forth statistical analyses showing that Lukan single traditions are disproportionately lacking in the Gospel of Marcion, while double and triple traditions are disproportionately present. They argue that this result makes sense if canonical Luke added new material to Marcion's gospel or its source, but that it is unlikely if Marcion removed material from Luke.

There are more nuanced variations and combinations of these hypotheses. Knox and Tyson, for example, follow the Semler hypothesis in general, but still posit with the Patristic hypothesis that Marcion removed some passages. Pier Angelo Gramaglia, in his critical translation of Klinghardt's edition, concurs with the overall direction of the Semler and Schwegler hypotheses, but has argued on philological grounds that the Gospel of Marcion and Luke are two successive editions by the same editor.[6] Like several 19th century scholars, Knox, Tyson, Vinzent, and Klinghardt have extended the Schwegler hypothesis to include the canonical Book of Acts, arguing that it is an anti-Marcionite work.[41][5][4]

Judith Lieu argues that Marcion had access and edited a work extremely similar to the Canonical Gospel of Luke, though this older work would have lacked certain passages. As such the currently extant Gospel of Luke would have appeared after the Gospel of Marcion. [42]

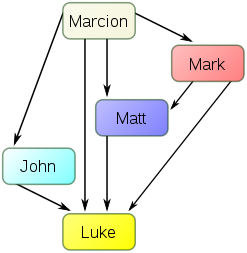

As a version of Mark

[edit]In 2008, Matthias Klinghardt proposed that Marcion's gospel was based on the Gospel of Mark, that the Gospel of Matthew was an expansion of the Gospel of Mark with reference to the Gospel of Marcion, and that the Gospel of Luke was an expansion of the Gospel of Marcion with reference to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark. In Klinghardt's view, this model elegantly accounts for the double tradition— material shared by Matthew and Luke, but not Mark— without appealing to purely hypothetical documents, such as the Q source.[38]: 21–22, 26 In his 2015 book, Klinghardt changed his opinion compared to his 2008 article. In his 2015 book, he considers that the gospel of Marcion precedes and influenced the four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John).[43]

As a two source gospel

[edit]In his 2013 book, BeDuhn argued that understanding Marcion's Gospel as the first two source gospel, drawing on Q and Mark, resolves many of the problems of the traditional Q hypothesis, including its narrative introduction and the minor agreements. [44] Pier Angelo Gramaglia, in his 2017 critical commentary on Klinghardt's reconstruction, made an extended argument that Marcion's Gospel is a two-source gospel, making use of Mark and Q, while canonical Luke builds on Marcion's Gospel in part from a secondary appropriation of Q material.[6] Research from 2018 suggests that the Gospel of Marcion may have been the original two-source gospel based on Q and Mark.[45]

As the first gospel

[edit]

In his 2014 book Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, Markus Vinzent considers, like Klinghardt, that the gospel of Marcion precedes the four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). He believes that the Gospel of Marcion influenced the four gospels. Vinzent differs with both BeDuhn and Klinghardt in that he believes the Gospel of Marcion was written directly by Marcion: Marcion's gospel was first written as a draft not meant for publication which was plagiarized by the four canonical gospels; this plagiarism angered Marcion who saw the purpose of his text distorted and made him publish his gospel along with a preface (the Antithesis) and 10 letters of Paul.[32][48][34]

The Marcion priority also implies a model of the late dating of the New Testament Gospels to the 2nd century - a thesis that goes back to David Trobisch, who, in 1996 in his habilitation thesis accepted in Heidelberg,[49] presented the conception or thesis of an early, uniform final editing of the New Testament canon in the 2nd century.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Clivaz, Claire (2005). "The Angel and the Sweat Like "Drops of Blood" (Lk 22:43–44):69 and ƒ13". Harvard Theological Review. 98 (4): 419–440. doi:10.1017/S0017816005001045. ISSN 0017-8160.

- ^ Bernier, Jonathan (2022). Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4934-3467-1.

According to late second- and early third-century fathers, Marcion (who was active in Rome in probably the 140s) produced a version of Luke's Gospel shorn of material that he found to be doctrinally unacceptable. For the most part, critical scholarship has been content to affirm these patristic reports.

- ^ a b c BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Salem, Oregon: Polebridge Press. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Klinghardt, Matthias (2021). The oldest gospel and the formation of the canonical gospels. Biblical Tools and Studies (2nd ed.). Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-4310-0. OCLC 1238089165. 2 volumes.

- ^ a b Vinzent, Markus (2014). Marcion and the dating of the synoptic gospels. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-3027-8. OCLC 870847884.

- ^ a b c Gramaglia, Pier Angelo (2017-09-27). Marcione e il Vangelo (di Luca) : un confronto con Matthias Klinghardt [Marcion and the Gospel (of Luke): A dialogue with Matthias Klinghardt] (in Italian). Matthias Klinghardt (1st ed.). Torino: Accademia University Press. ISBN 978-88-99982-37-9. OCLC 1264710161.

- ^ a b Marcion of Sinope (2019). Gianotto, Claudio; Nicolotti, Andrea (eds.). Il Vangelo di Marcione. Torino: Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-23141-5. OCLC 1105616974.

- ^ Thilo, Johann Karl (1832). Codex apocryphus Novi Testamenti. Leipzig: F.C.G. Vogel.

- ^ von Harnack, Adolf (1921). Marcion: das Evangelium vom fremden Gott, eine Monographie zur Geschichte der Grundlegung der katholischen Kirche [Marcion: the gospel of the alien God: A monograph on the history of the foundation of the Catholic Church]. Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur (1st ed.). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

- ^ Roth, Dieter T. (2015-01-08). The text of Marcion's Gospel. New Testament Tools, Studies and Documents. Vol. 49. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004282377. ISBN 978-90-04-24520-4.

- ^ Roth, Dieter T. (2015-01-08). "Epiphanius as a source". The text of Marcion's Gospel. New Testament Tools, Studies and Documents. Vol. 49. Leiden: Brill. pp. 270–346. doi:10.1163/9789004282377_007. ISBN 978-90-04-24520-4.

- ^ Tertullian. Adversus Marcionem. 4.7.1.

- ^ Epiphanius. Panarion. 42.11.4.

- ^ a b BeDuhn, Jason David. "The New Marcion" (PDF). Forum. 3 (Fall 2015): 163–179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ^ a b c Knox, John (1942). Marcion and the New Testament: An essay in the early history of the canon. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 978-0-598-89060-3.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). "The Evangelion". The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Polebridge Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2003). Lost Christianities. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-514183-2.

Tertullian, Epiphanius, and other ancient witnesses, all of whom knew and accepted the same Gospel of Luke we know, felt not the slightest doubt that the "heretic" had shortened and "mutilated" the canonical Gospel; and on the other hand, there is every indication that the Marcionites denied this charge and accused the more conservative churches of having falsified and corrupted the true Gospel which they alone possessed in its purity. These claims are precisely what we would have expected from the two rival camps, and neither set of them deserves much consideration.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce (1989) [1987]. "IV. Influences Bearing on the Development of the New Testament". The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origins, Developments and Significance (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 92–99.

- ^ Tertullian. Adversus Marcionem. 4.6.2.

- ^ a b von Harnack, Adolf (1990). Marcion: The Gospel of the Alien God. Translated by Steely, John E.; Bierma, Lyle D. Durham, North Carolina: Labrynth Press. ISBN 978-0-939464-16-6. A translation of von Harnack, Adolf (1924). Marcion: das Evangelium vom fremden Gott, eine Monographie zur Geschichte der Grundlegung der katholischen Kirche [Marcion: the gospel of the alien God: A monograph on the history of the foundation of the Catholic Church] (in German) (2nd ed.). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. Republished as von Harnack, Adolf (2007). Marcion: The Gospel of the Alien God. Translated by Steely, John E.; Bierma, Lyle D. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-55635-703-9.

- ^ a b c BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). "The Evangelion". The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Polebridge Press. pp. 78–79, 346–347. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Salem, Oregon: Polebridge Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ Löffler, Josias Friedrich Christian (1788). Marcionem Paulli epistolas et Lucae evangelium adulterasse dubitatur [It is doubtful that Marcion adulterated Paul's letters and Luke's gospel] (in Latin). Christian Ludwig Apitz. Republished as — (1794). "Marcionem Paulli epistolas et Lucae evangelium adulterasse dubitatur". Commentationes Theologicae (in Latin). 1: 180–218.

- ^ Schmidt, Johann Ernst Christian (1796). "Ueber das ächte Evangelium des Lucas, eine Vermuthung". Magazin für Religionsphilosophie, Exegese und Kirchengeschichte. 5: 468–520.

- ^ Bertholdt, Leonhard (1813). Historisch-kritische Einleitung in sämmtliche kanonische und apokryphische Schriften des alten und neuen Testaments [Historical-critical introduction to all canonical and apocryphal writings of the Old and New Testaments] (in German). Erlangen: Johann Jacob Palm. 5 volumes.

- ^ Tyson, Joseph B. (2006). Marcion and Luke-Acts : a defining struggle. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-650-0. OCLC 67383634.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). "The Evangelion". The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Polebridge Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ Albert Schwegler, Das nachapostolische Zeitalter in den Hauptmomenten seiner Entwicklung, 2 vol. (Tübingen: Fues., 1846)

- ^ Ritschl, Albrecht (1846). Das Evangelium Marcions und das kanonische Evangelium des Lucas: eine kritische Untersuchung [The Gospel of Marcion and the canonical Gospel of Luke: A critical study] (in German). Tübingen: Osiander. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Baur, Ferdinand Christian (1847). Kritische Untersuchungen über die kanonischen Evangelien, ihr Verhältnis zu einander, ihren Charakter und Ursprung [Critical studies of the canonical Gospels, their relationship to one another, their character and origin] (in German). Tübingen: Ludwig Friedrich Fues.

- ^ Hoffmann, R. Joseph (1984). Marcion, on the restitution of Christianity: An essay on the development of radical Paulinist theology in the second century. Scholars Press. ISBN 0-89130-638-2. OCLC 926802543.

- ^ a b Vinzent, Markus (2015). "Marcion's Gospel and the beginnings of early Christianity". Annali di Storia dell'esegesi. 32 (1): 55–87 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2015). "Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, written by Markus Vinzent". Vigiliae Christianae. 69 (4): 452–457. doi:10.1163/15700720-12301234. ISSN 1570-0720.

- ^ a b Vinzent, Markus (2016-11-24). "I am in the process of reading your book 'Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels' ..." Markus Vinzent's Blog. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ Trobisch, David (2018). "The Gospel According to John in the light of Marcion's Gospelbook". In Heilmann, Jan; Klinghardt, Matthias (eds.). Das Neue Testament und sein Text im 2.Jahrhundert [The New Testament and its text in the second century]. Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter (in German). Vol. 61. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-3-7720-8640-3.

- ^ Klinghardt, Matthias (2008). "The Marcionite Gospel and the synoptic problem: A new suggestion". Novum Testamentum. 50 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1163/156853608X257527. ISSN 0048-1009. JSTOR 25442581.

The main argument against the traditional view of Luke's priority to [Marcion] relies on the lack of consequence of his redaction: Marcion presumably had theological reasons for the alterations in "his" gospel which implies that he pursued an editorial concept. This, however, cannot be detected. On the contrary, all the major ancient sources give an account of Marcion's text, because they specifically intend to refute him on the ground of his own gospel. Therefore, Tertullian concludes his treatment of [Marcion]: "I am sorry for you, Marcion: your labour has been in vain. Even in your gospel Christ Jesus is mine" ([Tert. Adv. Marc.] 4.43.9).

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2012). "The myth of Marcion as redactor: The evidence of 'Marcion's' Gospel against an assumed Marcionite redaction". Annali di Storia dell'esegesi. 29 (1): 21–48. ISSN 1120-4001.

- ^ a b Klinghardt, Matthias (2008). "The Marcionite Gospel and the synoptic problem: A new suggestion". Novum Testamentum. 50 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1163/156853608X257527. JSTOR 25442581.

- ^ Tyson, Joseph (2006). Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1570036507.

- ^ Smith, Daniel A. (December 3, 2018). "Marcion's gospel and the synoptics: Proposals and problems". In Verheyden, Joseph; Nicklas, Tobias; Schröter, Jens (eds.). Gospels and Gospel Traditions in the Second Century: Experiments in Reception. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft. Vol. 235. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 129–174. doi:10.1515/9783110542349-008. ISBN 978-3-11-054081-9. ISSN 0171-6441. OCLC 1019604896.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). "The Evangelion". The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Polebridge Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ Lieu, Judith (26 March 2015). Marcion and the Making of a Heretic: God and Scripture in the Second Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-1107029040.

- ^ Klinghardt, Matthias (2015-03-25). "Vom ältesten Evangelium zum kanonischen Vier-Evangelienbuch: Eine überlieferungsgeschichtliche Skizze" [From the oldest gospel to the canonical books of the four gospels: A historical sketch]. Das älteste Evangelium und die Entstehung der kanonischen Evangelien: Band I: Untersuchung [The oldest gospel and the formation of the canonical gospels: Volume I: Investigation] (in German). Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. pp. 190–231. ISBN 978-3-7720-5549-2. ISSN 0939-5199.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). "The Evangelion". The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Polebridge Press. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ Bilby, Mark G. (2018-10-05). "First Dionysian gospel: Imitational and redactional layers in Luke and John". In Bilby, Mark G.; Kochenash, Michael; Froelich, Margaret (eds.). Classical Greek models of the Gospels and Acts: Studies in mimesis criticism. Claremont studies in New Testament & Christian origins. Claremont, CA: Claremont Press. pp. 49–68. ISBN 978-1-946230-18-8.

- ^ Klinghardt, Matthias (2015-03-25). "Vom ältesten Evangelium zum kanonischen Vier-Evangelienbuch: Eine überlieferungsgeschichtliche Skizze" [From the oldest gospel to the canonical books of the four gospels: A historical sketch]. Das älteste Evangelium und die Entstehung der kanonischen Evangelien: Band I: Untersuchung [The oldest gospel and the formation of the canonical gospels: Volume I: Investigation] (in German). Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. p. 193. ISBN 978-3-7720-8549-9. ISSN 0939-5199.

- ^ Klinghardt, Matthias (14 December 2020). "Vom ältesten Evangelium zum kanonischen Vier-Evangelienbuch: Eine überlieferungsgeschichtliche Skizze" [From the oldest gospel to the canonical books of the four gospels: A historical sketch]. Das älteste Evangelium und die Entstehung der kanonischen Evangelien: Band I: Untersuchung [The oldest gospel and the formation of the canonical gospels: Volume I: Investigation]. Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter (in German) (2nd ed.). Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. p. 210. ISBN 978-3-7720-8742-4.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2015-09-16). "Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, written by Markus Vinzent". Vigiliae Christianae. 69 (4): 452–457. doi:10.1163/15700720-12301234. ISSN 1570-0720.

- ^ Trobisch, David (1996). Die Endredaktion des Neuen Testaments : eine Untersuchung zur Entstehung der christlichen Bibel (in German). Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätsverlag. ISBN 3-7278-1075-0. OCLC 35782011.

- ^ Heilmann, Jan; Klinghardt, Matthias (2018). "Eine Einführung" [An introduction] (PDF). In Heilmann, Jan; Klinghardt, Matthias (eds.). Das Neue Testament und sein Text im 2.Jahrhundert [The New Testament and its text in the second century]. Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter. Vol. 61. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. p. 9. ISBN 978-3-7720-8640-3.

Die Ausgangsthese einer Edition des Neuen Testaments im 2. Jh. ist nicht neu. Sie geht auf David Trobisch zurück, der schon vor 20 Jahren herausgearbeitet hatte, dass die 27 Einzelschriften des NT nicht in einem längeren, anonymen Sammlungs- und Ausscheidungsprozess zu einer literarischen (und theologischen) Einheit zusammengewachsen sind. 1 Diese Einheit sei vielmehr das Produkt einer einmaligen, historisch in der Mitte des 2. Jh. zu verortenden Edition. Diese Ausgabe trug bereits den Titel „Neues Testament" (η῾ καινη` διαθη´ κη) und war von vornherein als zweiter Teil einer christlichen Bibel, also mit dem Blick auf das „Alte Testament" konzipiert. [The initial thesis of an edition of the New Testament in the 2nd century is not new. It goes back to David Trobisch, who had already worked out 20 years ago that the 27 individual writings of the NT did not grow together into a literary (and theological) unit through a long, anonymous process of collection and elimination. Rather, this unity is the product of a unique edition that can be historically located in the middle of the 2nd century. This edition already had the title "New Testament" (η῾ καινη` διαθη´ κη) and was conceived from the outset as the second part of a Christian Bible, i.e. with the "Old Testament" in mind.]

External links

[edit]- The Marcionite Research Library: contains a full text in English with hyperlinks to the reconstruction sources.

- BeDuhn, Jason David (2013). The first New Testament: Marcion's scriptural canon. Polebridge Press. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2.: a full modern English reconstruction available for checkout at the Open Library

Further reading

[edit]- G.R.S. Mead, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten (London and Benares, 1900; 3rd edition 1931): pp. 241– 249 Introduction to Marcion

- Burkitt, Francis Crawford (1906). "Marcion, or Christianity without history". The Gospel History and Its Transmission. Jowett lectures (1st ed.). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 289–323. 5th edition (1925) HTML

- Waite, Charles Burlingame (1881). History of the Christian Religion to the Year Two-Hundred. Chicago: C. V. Waite & Company. It includes a chapter where he compares Marcion and Luke

- Tyson, Joseph B. (2006). Marcion and Luke-Acts: A defining struggle. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-650-7. A case in favor of the view that the canonical Luke-Acts duo is a response to Marcion. Tyson also recounts the history of scholarly studies on Marcion up to 2006.