This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

|

| This article is one of a series on: |

| Life in the universe |

|---|

| Outline |

| Planetary habitability in the Solar System |

| Life outside the Solar System |

| Habitability of... |

The theorized habitability of red dwarf systems is determined by a large number of factors. Modern evidence suggests that planets in red dwarf systems are unlikely to be habitable, due to high probability of tidal locking, likely lack of atmospheres, and the high stellar variation many such planets would experience. However, the sheer number and longevity of red dwarfs could likely provide ample opportunity to realize any small possibility of habitability.

Current arguments concerning the habitability of red dwarf systems are unresolved, and the area remains an open question of study in the fields of climate modeling and the evolution of life on Earth. Observational data and statistical arguments suggest that red dwarf systems are uninhabitable for indeterminate reasons.[1] On the other hand, 3D climate models favor habitability[2] and wider habitable zones for slow rotating and tidally locked planets.[3]

A major impediment to the development of life in red dwarf systems is the intense tidal heating caused by the eccentric orbits of planets around their host stars.[4][5] Other tidal effects reduce the probability of life around red dwarfs, such as the lack of planetary axial tilts and the extreme temperature differences created by one side of planet permanently facing the star and the other perpetually turned away. Still, a planetary atmosphere may redistribute the heat, making temperatures more uniform.[6][5] However, it is important to bear in mind that many red dwarfs are flare stars, and their flare events could greatly reduce the habitability of their satellites by eroding their atmosphere (though a planetary magnetic field could protect from these flares).[7] Non-tidal factors further reduce the prospects for life in red-dwarf systems, such as spectral energy distributions shifted toward the infrared side of the spectrum relative to the Sun and small circumstellar habitable zones due to low light output.[5]

There are, however, a few factors that could increase the likelihood of life on red dwarf planets. Intense cloud formation on the star-facing side of a tidally locked planet can likely reduce overall thermal flux and equilibrium temperature differences between the two sides of the planet.[8] In addition, the sheer number of red dwarfs statistically increases the probability that there might exist habitable planets orbiting some of them. Red dwarfs account for about 85% of stars in the Milky Way[9][10] and constitute the vast majority of stars in spiral and elliptical galaxies. There are expected to be tens of billions of super-Earth planets in the habitable zones of red dwarf stars in the Milky Way.[11] Investigating the habitability of red dwarf star systems could help determine the frequency of life in the universe and aid scientific understanding of the evolution of life.

Background

[edit]Red dwarfs[12] are the smallest, coolest, and most common type of star. Estimates of their abundance range from 70% of stars in spiral galaxies to more than 90% of all stars in elliptical galaxies,[13][14] an often quoted median figure being 72–76% of the stars in the Milky Way (known since the 1990s from radio telescopic observation to be a barred spiral).[15] Red dwarfs are usually defined as being of spectral type M, although some definitions are wider (including also some or all K-type stars). Given their low energy output, red dwarfs are almost never naked-eye visible from Earth: the closest red dwarf to the Sun, Proxima Centauri, is nowhere near visual magnitude. The brightest red dwarf in Earth's night sky, Lacaille 8760 (+6.7) is visible to the naked eye only under ideal viewing conditions.

Longevity and ubiquity

[edit]Red dwarfs’ greatest advantage as candidate stars for life is their longevity. It took 4.5 billion years for intelligent life to evolve on Earth, and life as we know it will see suitable conditions for 1[16] to 2.3[17] billion years more. Red dwarfs, by contrast, could live for trillions of years, as their nuclear reactions are far slower than those of larger stars,[a] meaning that life would have longer to evolve and survive.

While the likelihood of finding a planet in the habitable zone around any specific red dwarf is slight, the total amount of habitable zone around all red dwarfs combined is equal to the total amount around Sun-like stars, given their ubiquity.[18] Furthermore, this total amount of habitable zone will last longer, because red dwarf stars live for hundreds of billions of years or even longer on the main sequence,[19] potentially allowing for the evolution of microbial or intelligent life in the future.

Luminosity and spectral composition

[edit]

For years, astronomers have been pessimistic about red dwarfs as potential candidates for hosting life. The low masses of red dwarves (from roughly 0.08 to 0.60 solar masses (M☉)) cause their nuclear fusion reactions to proceed exceedingly slowly, giving them low luminosities ranging from 10% to just 0.0125% that of the Earth's Sun.[20] Consequently, any planet orbiting a red dwarf would need a low semi-major axis in order to maintain an Earth-like surface temperature, from 0.268 astronomical units (AU) for a relatively luminous red dwarf like Lacaille 8760 to 0.032 AU for a smaller star like Proxima Centauri.[21] Such a world would have a year lasting just 3 to 150 Earth days.[22][23]

Photosynthesis on such a planet would be difficult, as much of the low luminosity falls under the lower energy infrared and red part of the electromagnetic spectrum, and would therefore require additional photons to achieve excitation potentials.[24] Potential plants would likely adapt to a much wider spectrum (and as such appear black in visible light).[24] However, further research, including a consideration of the amount of photosynthetically active radiation, has suggested that tidally locked planets in red dwarf systems might at least be habitable for higher plants.[25] Additionally, some bacteria, such as purple bacteria, have pigments such as bacteriochlorophyll which absorb infrared light, making at least hotter red dwarfs potentially suitable for photosynthetic life.

In addition, because water strongly absorbs red and infrared light, less energy would be available for aquatic life on red dwarf planets.[26] However, a similar effect of preferential absorption by water ice would increase its temperature relative to an equivalent amount of radiation from a Sun-like star, thereby extending the habitable zone of red dwarfs outward.[27]

The evolution of the red dwarf stars may also inhibit habitability. As red dwarf stars have an extended pre-main sequence phase, their eventual habitable zones would be for around 1 billion years in a zone where water was not liquid but rather in a gaseous state. Thus, terrestrial planets in the actual habitable zones, if provided with abundant surface water in their formation, would have been subject to a runaway greenhouse effect for several hundred million years. During such an early runaway greenhouse phase, photolysis of water vapor would allow hydrogen escape to space and the loss of several Earth oceans of water, leaving a thick abiotic oxygen atmosphere.[28] Nevertheless, photolysis could be at least slowed down with a sufficient ozone layer.

Since the lifespan of red dwarf stars exceeds the age of the known universe, the further evolution of red dwarfs is known only by theory and simulations. According to computer simulations, a red dwarf becomes a blue dwarf after exhausting its hydrogen supply. As this kind of star is more luminous than the previous red dwarf, planets orbiting it that were frozen during the former stage could be thawed during the several billions of years this evolutionary stage lasts (5 billion years, for example, for a 0.16 M☉ star), giving life an opportunity to appear and evolve.[29]

Tidal effects

[edit]For planets to retain significant amounts of water in the habitable zone of ultra-cool dwarfs, a planet must orbit very near to the star.[30] At these close orbital distances, tidal locking to the host star is likely. Tidal locking makes the planet rotate on its axis once every revolution around the star. As a result, one side of the planet would eternally face the star and another side would perpetually face away, creating great extremes of temperature.

For many years, it was believed that life on such planets would be limited to a ring-like region known as the terminator, where the star would always appear on or close to the horizon. It was also believed that efficient heat transfer between the sides of the planet necessitates atmospheric circulation of an atmosphere so thick as to disallow photosynthesis. Due to differential heating, it was argued, a tidally locked planet would experience fierce winds with permanent torrential rain at the point directly facing the local star,[31] the sub-solar point. In the opinion of one author this makes complex life improbable.[32] Plant life would have to adapt to the constant gale, for example by anchoring securely into the soil and sprouting long flexible leaves that do not snap. Animals would rely on infrared vision, as signaling by calls or scents would be difficult over the din of the planet-wide gale. Underwater life would, however, be protected from fierce winds and flares, and vast blooms of black photosynthetic plankton and algae could support the sea life.[33]

In contrast to the previously bleak picture for life, 1997 studies by NASA's Ames Research Center have shown that a planet's atmosphere (assuming it included greenhouse gases CO2 and H2O) need only be 100 millibar, or 10% of Earth's atmosphere, for the star's heat to be effectively carried to the night side, a figure well within the bounds of photosynthesis.[34] Subsequent research has shown that seawater, too, could effectively circulate without freezing solid if the ocean basins were deep enough to allow free flow beneath the night side's ice cap. Additionally, a 2010 study concluded that Earth-like water worlds tidally locked to their stars would still have temperatures above 240 K (−33 °C) on the night side.[35] Climate models constructed in 2013 indicate that cloud formation on tidally locked planets would minimize the temperature difference between the day and the night side, greatly improving habitability prospects for red dwarf planets.[8]

The existence of a permanent day side and night side is not the only potential setback for life around red dwarfs. Tidal heating experienced by planets in the habitable zone of red dwarfs less than 30% of the mass of the Sun may cause them to be "baked out" and become "tidal Venuses."[4] The eccentricity of over 150 planets found orbiting M dwarfs was measured, and it was found that two-thirds of these exoplanets are exposed to extreme tidal forces, rendering them uninhabitable due to the intense heat generated by tidal heating.[36]

Combined with the other impediments to red dwarf habitability,[6] this may make the probability of many red dwarfs hosting life as we know it very low compared to other star types.[5] There may not even be enough water for habitable planets around many red dwarfs;[37] what little water found on these planets, in particular Earth-sized ones, may be located on the cold night side of the planet. In contrast to the predictions of earlier studies on tidal Venuses, though, this "trapped water" may help to stave off runaway greenhouse effects and improve the habitability of red dwarf systems.[38]

Note however that how quickly tidal locking occurs can depend upon a planet's oceans and even atmosphere, and it may mean that tidal locking fails to happen even after many billions of years. Additionally, tidal locking is not the only possible end state of tidal dampening. Mercury, for example, has had sufficient time to tidally lock, but is in a 3:2 spin orbit resonance due to an eccentric orbit.[39]

Variability

[edit]Red dwarfs are far more volatile than their larger, more stable cousins. Often, they are covered in starspots that can dim their emitted light by up to 40% for months at a time. At other times, red dwarfs emit gigantic flares that can double their brightness in a matter of minutes.[40] Indeed, as more and more red dwarfs have been scrutinized for variability, more of them have been classified as flare stars to some degree or other. Such variation in brightness could be very damaging for life. Recent 3D climate models simulate flare events by altering the stellar flux received by any given planet. One study found that, should a tidally locked planet possess a sufficient atmosphere, cloud coverage and albedo increase monotonically with stellar flux, increasing the resilience of the planet to variations in radiation.[8] This caveat has proven difficult, however, since flares produce torrents of charged particles that could strip off sizable portions of the planet's atmosphere.[41] Scientists who believe in the Rare Earth hypothesis doubt that red dwarfs could support life amid strong flaring. Tidal locking would probably result in a relatively low planetary magnetic moment. Active red dwarfs that emit coronal mass ejections (CMEs) would bow back the magnetosphere until it contacted the planetary atmosphere. As a result, the atmosphere would undergo strong erosion, possibly leaving the planet uninhabitable.[42][43][44] However, it was found that red dwarfs have a much lower CME rate than expected from their rotation or flare activity, and large CMEs occur rarely. This suggests that atmospheric erosion is caused mainly by radiation rather than CMEs.[45]

Otherwise, it is suggested that if the planet had a magnetic field, it would deflect the particles from the atmosphere (even the slow rotation of a tidally locked M-dwarf planet—it spins once for every time it orbits its star—would be enough to generate a magnetic field as long as part of the planet's interior remained molten).[46] This magnetic field should be much stronger compared to Earth's to give protection against flares of the observed magnitude (10–1000 G compared to Earth's ~0.5 G), which is unlikely to be generated.[47] Mathematical models additionally conclude that,[48][49][50] even under the highest attainable dynamo-generated magnetic field strengths, exoplanets with masses similar to that of Earth lose a significant fraction of their atmospheres by the erosion of the exobase's atmosphere by CME bursts and XUV emissions (even those Earth-like planets closer than 0.8 AU, affecting also G and K stars, are prone to losing their atmospheres). Atmospheric erosion could likely trigger the depletion of water oceans as well.[51] Planets shrouded by a thick haze of hydrocarbons, such as the ones on primordial Earth or Saturn's moon Titan might still survive the flares, as floating droplets of hydrocarbon are particularly efficient at absorbing ultraviolet radiation.[52]

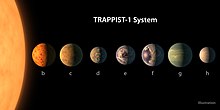

Measurements reject the presence of relevant atmospheres in two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf: TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c. The two planets are bare rocks, or have very thin atmospheres.[53] The rest of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, all of whom other than the exceptions of TRAPPIST-1h or possibly TRAPPIST-1d are in the habitable zone, are unlikely to have atmospheres, but their existence is not entirely ruled out. Other potentially habitable planets orbiting red dwarfs, such as LHS 1140b[54][55] or K2-18b[56] have likely atmospheres.

Another way that life could initially protect itself from radiation would be remaining underwater until the star had passed through its early flare stage, assuming the planet could retain enough of an atmosphere to sustain liquid oceans. Once life reached land, the low amount of UV produced by a quiet red dwarf means that life could thrive without an ozone layer, and thus never need to produce oxygen.[24]

Flare activity

[edit]For a planet around a red dwarf star to support life, it would require a rapidly rotating magnetic field to protect it from the flares. A tidally locked planet rotates slowly, and so may not be able to produce a geodynamo at its core. The violent flaring period of a red dwarf's life cycle is estimated to last for only about the first 1.2 billion years of its existence. If a planet forms far away from a red dwarf so as to avoid atmospheric erosion, and then migrates into the star's habitable zone after this turbulent initial period, it is possible for life to develop.[57] However, observations of the 7 to 12-billion year old Barnard's Star showcase that even old red dwarfs can have significant flare activity. Barnard's Star was long assumed to have little activity, but in 1998 astronomers observed an intense stellar flare, showing that it is a flare star.[58]

It has been found that the largest flares happen at high latitudes near the stellar poles; if an exoplanet's orbit is aligned with the stellar rotation (as is the case with the planets of the Solar System), then it is less affected by the flares than previously thought.[59]

Methane habitable zone

[edit]If methane-based life is possible (similar to the hypothetical life on Titan), there would be a second habitable zone further out from the star corresponding to the region where methane is liquid. Titan's atmosphere is transparent to red and infrared light, so more of the light from red dwarfs would be expected to reach the surface of a Titan-like planet.[60] This zone would lie at 2.573 astronomical units (AU) for Lacaille 8760, to 0.379 AU for Proxima Centauri.

Frequency of Earth-sized worlds around ultra-cool dwarfs

[edit]

A study of archival Spitzer data gives the first idea and estimate of how frequent Earth-sized worlds are around ultra-cool dwarf stars: 30–45%.[61] A computer simulation finds that planets that form around stars with similar mass to TRAPPIST-1 (c. 0.084 M⊙) most likely have sizes similar to the Earth's.[62]

In fiction

[edit]- Ark: In Stephen Baxter's Ark, after planet Earth is completely submerged by the oceans a small group of humans embark on an interstellar journey eventually making it to a planet named Earth III. The planet is cold, tidally locked and the plant life is black (in order to better absorb the light from the red dwarf).

- Draco Tavern: In Larry Niven's Draco Tavern stories, the highly advanced Chirpsithra aliens evolved on a tide-locked oxygen world around a red dwarf. However, no detail is given beyond that it was about 1 terrestrial mass, a little colder, and used red dwarf sunlight.

- Nemesis: Isaac Asimov avoids the tidal effect issues of the red dwarf Nemesis by making the habitable "planet" a satellite of a gas giant which is tidally locked to the star.

- Star Maker: In Olaf Stapledon's 1937 science fiction novel Star Maker, one of the many alien civilizations in the Milky Way he describes is located in the terminator zone of a tidally locked planet of a red dwarf system. This planet is inhabited by intelligent plants that look like carrots with arms, legs, and a head, which "sleep" part of the time by inserting themselves in soil on plots of land and absorbing sunlight through photosynthesis, and which are awake part of the time, emerging from their plots of soil as locomoting beings who participate in all the complex activities of a modern industrial civilization. Stapledon also describes how life evolved on this planet.[63]

- Superman: Superman's home, Krypton, was in orbit around a red star called Rao which in some stories is described as being a red dwarf, although it is more often referred to as a red giant.

- Ready Jet Go!: In the children's show Ready Jet Go!, Carrot, Celery and Jet are a family of aliens known as Bortronians who come from Bortron 7, a planet of the fictional red dwarf Bortron. They discovered Earth and the Sun when they picked up a "primitive" radio signal (Episode: "How We Found Your Sun"). They also gave a description of the planets in the Bortronian solar system in a song in the movie Ready Jet Go!: Back to Bortron 7.

- Aurelia: This planet, seen in the speculative documentary Extraterrestrial (also known as Alien Worlds), details what scientist theorize alien life could be like on a planet orbiting a red dwarf star.

See also

[edit]- Acaryochloris marina

- Astrobiology

- Circumstellar habitable zone

- Gliese 581g

- Habitability of F-type main-sequence star systems

- Habitability of K-type main-sequence star systems

- Habitability of neutron star systems

- Habitability of yellow dwarf systems

- Kepler-186f

- Planetary habitability

- Search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI)

![]() Learning materials from Wikiversity:

Learning materials from Wikiversity:

Notes

[edit]- ^ The more massive a star is, the shorter it lives.

References

[edit]- ^ Waltham, David (January 2017). "Star Masses and Star-Planet Distances for Earth-like Habitability". Astrobiology. 17 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1089/ast.2016.1518. PMC 5278800. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Yang, Jun; Cowan, Nicolas B.; Abbot, Dorian S. (27 June 2013). "STABILIZING CLOUD FEEDBACK DRAMATICALLY EXPANDS THE HABITABLE ZONE OF TIDALLY LOCKED PLANETS". The Astrophysical Journal. 771 (2): L45. arXiv:1307.0515. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/771/2/L45. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Yang, Jun; Boué, Gwenaël; Fabrycky, Daniel C.; Abbot, Dorian S. (25 April 2014). "STRONG DEPENDENCE OF THE INNER EDGE OF THE HABITABLE ZONE ON PLANETARY ROTATION RATE". The Astrophysical Journal. 787 (1): L2. arXiv:1404.4992. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/787/1/L2. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ a b Barnes, Rory; Mullins, Kristina; Goldblatt, Colin; Meadows, Victoria S.; Kasting, James F.; Heller, René (March 2013). "Tidal Venuses: Triggering a Climate Catastrophe via Tidal Heating". Astrobiology. 13 (3): 225–250. arXiv:1203.5104. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..225B. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0851. PMC 3612283. PMID 23537135.

- ^ a b c d Major, Jason (23 December 2015). ""Tidal Venuses" May Have Been Wrung Out To Dry". Universetoday.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Alasdair (2012-01-16). "Life might not be possible around red dwarf stars". Io9.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ "Habitable Exoplanet Observatory (HabEx)". www.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-10-08. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ a b c Yang, J.; Cowan, N. B.; Abbot, D. S. (2013). "Stabilizing Cloud Feedback Dramatically Expands the Habitable Zone of Tidally Locked Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 771 (2): L45. arXiv:1307.0515. Bibcode:2013ApJ...771L..45Y. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/771/2/L45. S2CID 14119086.

- ^ Than, Ker (2006-01-30). "Astronomers Had it Wrong: Most Stars are Single". Space.com. TechMediaNetwork. Archived from the original on 2019-09-24. Retrieved 2013-07-04.

- ^ Staff (2013-01-02). "100 Billion Alien Planets Fill Our Milky Way Galaxy: Study". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2020-05-09. Retrieved 2013-01-03.

- ^ Gilster, Paul (2012-03-29). "ESO: Habitable Red Dwarf Planets Abundant". Centauri-dreams.org. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ The term dwarf applies to all stars in the main sequence, including the Sun.

- ^ van Dokkum, Pieter G.; Conroy, Charlie (1 December 2010). "A substantial population of low-mass stars in luminous elliptical galaxies". Nature. 468 (7326): 940–942. arXiv:1009.5992. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..940V. doi:10.1038/nature09578. PMID 21124316. S2CID 205222998.

- ^ Yale University (December 1, 2010). "Discovery Triples Number of Stars in Universe". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on January 4, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Dole, Stephen H. Habitable Planets for Man 1965 Rand Corporation report, published in book form--A figure of 73% is given for the percentage of red dwarfs in the Milky Way.

- ^ Hines, Sandra (13 January 2003). "'The end of the world' has already begun, UW scientists say" (Press release). University of Washington. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ^ Li, King-Fai; Pahlevan, Kaveh; Kirschvink, Joseph L.; Yung, Yuk L. (2009). "Atmospheric pressure as a natural climate regulator for a terrestrial planet with a biosphere" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (24): 9576–9579. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9576L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809436106. PMC 2701016. PMID 19487662. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ "M Dwarfs: The Search for Life is On, Interview with Todd Henry". Astrobiology Magazine. 29 August 2005. Archived from the original on 2011-06-03. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (4 February 2009). "Red Dwarf Stars". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ Chabrier, G.; Baraffe, I.; Plez, B. (1996). "Mass-Luminosity Relationship and Lithium Depletion for Very Low Mass Stars". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 459 (2): L91 – L94. Bibcode:1996ApJ...459L..91C. doi:10.1086/309951.

- ^ "Habitable zones of stars". NASA Specialized Center of Research and Training in Exobiology. University of Southern California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 2000-11-21. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- ^ Ségransan, Damien; Kervella, Pierre; Forveille, Thierry; Queloz, Didier (2003). "First radius measurements of very low mass stars with the VLTI". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 397 (3): L5 – L8. arXiv:astro-ph/0211647. Bibcode:2003A&A...397L...5S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021714. S2CID 10748478.

- ^ Williams, David R. (2004-09-01). "Earth Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ a b c Kiang, Nancy Y. (April 2008). "The color of plants on other worlds". Scientific American. 298 (4): 48–55. Bibcode:2008SciAm.298d..48K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0408-48. PMID 18380141. S2CID 12329051.

- ^ Heath, Martin J.; Doyle, Laurance R.; Joshi, Manoj M.; Haberle, Robert M. (1999). "Habitability of Planets Around Red Dwarf Stars" (PDF). Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere. 29 (4): 405–424. Bibcode:1999OLEB...29..405H. doi:10.1023/A:1006596718708. PMID 10472629. S2CID 12329736. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ Hoejerslev, N. K. (1986). "3.3.2.1 Optical properties of pure water and pure sea water". Subvolume A. Landolt-Börnstein - Group V Geophysics. Vol. 3a. pp. 395–398. doi:10.1007/10201933_90. ISBN 978-3-540-15092-3.

- ^ Joshi, M.; Haberle, R. (2012). "Suppression of the water ice and snow albedo feedback on planets orbiting red dwarf stars and the subsequent widening of the habitable zone". Astrobiology. 12 (1): 3–8. arXiv:1110.4525. Bibcode:2012AsBio..12....3J. doi:10.1089/ast.2011.0668. PMID 22181553. S2CID 18065288.

- ^ Luger, R.; Barnes, R. (2014). "Extreme Water Loss and Abiotic O2 Buildup on Planets Throughout the Habitable Zones of M Dwarfs". Astrobiology. 15 (2): 119–143. arXiv:1411.7412. Bibcode:2015AsBio..15..119L. doi:10.1089/ast.2014.1231. PMC 4323125. PMID 25629240.

- ^ Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory; Graves, Genevieve J. M. "Red Dwarfs and the End of the Main Sequence". Gravitational Collapse: From Massive Stars to Planets. Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. pp. 46–49. Bibcode:2004RMxAC..22...46A.

- ^ Bolmont, E.; Selsis, F.; Owen, J. E.; Ribas, I.; Raymond, S. N.; Leconte, J.; Gillon, M. (21 January 2017). "Water loss from terrestrial planets orbiting ultracool dwarfs: implications for the planets of TRAPPIST-1". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 464 (3): 3728–3741. arXiv:1605.00616. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.464.3728B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2578.

- ^ Joshi, M. (2003). "Climate model studies of synchronously rotating planets". Astrobiology. 3 (2): 415–427. Bibcode:2003AsBio...3..415J. doi:10.1089/153110703769016488. PMID 14577888.

- ^ "Gliese 581d". Astroprof’s Page. 16 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (April 2010). "Meet the Alien Neighbours: Red Dwarf World". Focus: 45. Archived from the original on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ^ Joshi, M. M.; Haberle, R. M.; Reynolds, R. T. (October 1997). "Simulations of the Atmospheres of Synchronously Rotating Terrestrial Planets Orbiting M Dwarfs: Conditions for Atmospheric Collapse and the Implications for Habitability" (PDF). Icarus. 129 (2): 450–465. Bibcode:1997Icar..129..450J. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5793. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-15. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ Merlis, T. M.; Schneider, T. (2010). "Atmospheric dynamics of Earth-like tidally locked aquaplanets". Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems. 2 (4): n/a. arXiv:1001.5117. Bibcode:2010JAMES...2...13M. doi:10.3894/JAMES.2010.2.13. S2CID 37824988.

- ^ Sagear, Sheila; Ballards, Sarah (2023). "The Orbital Eccentricity Distribution of Planets Orbiting M dwarfs". PNAS. XXX (XX): e2217398120. arXiv:2305.17157. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12017398S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2217398120. PMC 10265968. PMID 37252955. S2CID 258960478.

- ^ Lissauer, Jack J. (2007). "Planets formed in habitable zones of M dwarf stars probably are deficient in volatiles". The Astrophysical Journal. 660 (2): 149–152. arXiv:astro-ph/0703576. Bibcode:2007ApJ...660L.149L. doi:10.1086/518121. S2CID 12312927.

- ^ Menou, Kristen (16 August 2013). "Water-Trapped Worlds". The Astrophysical Journal. 774 (1): 51. arXiv:1304.6472. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774...51M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/774/1/51. S2CID 118363386.

- ^ Kasting, James F.; Whitmire, Daniel P.; Reynolds, Ray T. (1993). "Habitable Zones around Main Sequence Stars" (PDF). Icarus. 101 (1): 108–128. Bibcode:1993Icar..101..108K. doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1010. PMID 11536936. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-26. Retrieved 2017-08-03.

- ^ Croswell, Ken (27 January 2001). "Red, willing and able". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ Guinan, Edward F.; Engle, S. G.: "Future Interstellar Travel Destinations: Assessing the Suitability of Nearby Red Dwarf Stars as Hosts to Habitable Life-bearing Planets"; American Astronomical Society, AAS Meeting #221, #333.02 Publication Date:01/2013 Bibcode:2013AAS...22133302G

- ^ Khodachenko, Maxim L.; et al. (2007). "Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) Activity of Low Mass M Stars as An Important Factor for The Habitability of Terrestrial Exoplanets. I. CME Impact on Expected Magnetospheres of Earth-Like Exoplanets in Close-In Habitable Zones". Astrobiology. 7 (1): 167–184. Bibcode:2007AsBio...7..167K. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.0127. PMID 17407406.

- ^ Kay, C.; et al. (2016). "Probability of Cme Impact on Exoplanets Orbiting M Dwarfs and Solar-Like Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 826 (2): 195. arXiv:1605.02683. Bibcode:2016ApJ...826..195K. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/826/2/195. S2CID 118669187.

- ^ Garcia-Sage, K.; et al. (2017). "On the Magnetic Protection of the Atmosphere of Proxima Centauri b". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 844 (1): L13. Bibcode:2017ApJ...844L..13G. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa7eca. S2CID 126391408.

- ^ K., Vida (2019). "The quest for stellar coronal mass ejections in late-type stars. I. Investigating Balmer-line asymmetries of single stars in Virtual Observatory data". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 623 (14): A49. arXiv:1901.04229. Bibcode:2019A&A...623A..49V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834264. S2CID 119095055.

- ^ Alpert, Mark (November 1, 2005). "Red Star Rising: Small, cool stars may be hot spots for life". Scientific American. 293 (5): 28. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293e..28A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1105-28. PMID 16318021. Archived from the original on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ K., Vida (2017). "Frequent flaring in the TRAPPIST-1 system - unsuited for life?". The Astrophysical Journal. 841 (2): 124. arXiv:1703.10130. Bibcode:2017ApJ...841..124V. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa6f05. S2CID 118827117.

- ^ Zuluaga, J. I.; Cuartas, P. A.; Hoyos, J. H. (2012). "Evolution of magnetic protection in potentially habitable terrestrial planets". arXiv:1204.0275 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ See, V.; Jardine, M.; Vidotto, A. A.; Petit, P.; Marsden, S. C.; Jeffers, S. V.; do Nascimento, J. D. (30 October 2014). "The effects of stellar winds on the magnetospheres and potential habitability of exoplanets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 570: A99. arXiv:1409.1237. Bibcode:2014A&A...570A..99S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424323. S2CID 16146794.

- ^ Dong, Chuanfei; Lingam, Manasvi; Ma, Yingjuan; Cohen, Ofer (10 March 2017). "Is Proxima Centauri b Habitable? A Study of Atmospheric Loss". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 837:L26 (2): L26. arXiv:1702.04089. Bibcode:2017ApJ...837L..26D. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa6438. S2CID 118927765.

- ^ Dong, Chuanfei; et al. (2017). "The dehydration of water worlds via atmospheric losses". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 847 (L4): L4. arXiv:1709.01219. Bibcode:2017ApJ...847L...4D. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa8a60. S2CID 119424858.

- ^ Tilley, Matt A; et al. (22 Nov 2017). "Modeling Repeated M-dwarf Flaring at an Earth-like Planet in the Habitable Zone: I. Atmospheric Effects for an Unmagnetized Planet". Astrobiology. 19 (1): 64–86. arXiv:1711.08484. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1794. PMC 6340793. PMID 30070900.

- ^ Zleba, Sebastian; Kreldberg, Laura (19 June 2023). "No thick carbon dioxide atmosphere on the rocky exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 c". Nature. 620 (7975): 746–749. arXiv:2306.10150. Bibcode:2023Natur.620..746Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06232-z. PMC 10447244. PMID 37337068. S2CID 259200424.

- ^ Damiano, Mario; Bello-Arufe, Aaron; et al. (March 2024). "LHS 1140 b is a potentially habitable water world". arXiv:2403.13265 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ "Habitable Zone Exoplanet LHS 1140b is Probably Snowball or Water World | Sci.News". Sci.News: Breaking Science News. 2024-07-09. Retrieved 2024-07-10.

- ^ Madhusudhan, Nikku; Nixon, Matthew C.; Welbanks, Luis; Piette, Anjali A. A.; Booth, Richard A. (February 2020). "The Interior and Atmosphere of the Habitable-zone Exoplanet K2-18b". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 891 (1): L7. arXiv:2002.11115. Bibcode:2020ApJ...891L...7M. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab7229. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 211505592.

- ^ Cain, Fraser; Gay, Pamela (2007). "AstronomyCast episode 40: American Astronomical Society Meeting, May 2007". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- ^ Croswell, Ken (November 2005). "A Flare for Barnard's Star". Astronomy Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing Co. Archived from the original on 2015-02-24. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ^ Ilin, Ekaterina; Poppenhaeger, Katja; et al. (5 August 2021). "Giant white-light flares on fully convective stars occur at high latitudes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 507 (2): 1723–1745. arXiv:2108.01917. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab2159.

- ^ Cooper, Keith (10 November 2011). "The Methane Habitable Zone". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-05-09. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ He, Matthias Y.; Triaud, Amaury H. M. J.; Gillon, Michaël (2017). "First limits on the occurrence rate of short-period planets orbiting brown dwarfs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 464 (3): 2687–2697. arXiv:1609.05053. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.464.2687H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2391.

- ^ Alibert, Yann; Benz, Willy (26 January 2017). "Formation and composition of planets around very low mass stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 598: L5. arXiv:1610.03460. Bibcode:2017A&A...598L...5A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629671. S2CID 54002704.

- ^ Stapledon, Olaf Star Maker 1937 Chapter 7 "More Worlds" Part 3 "Plant Men and Others"

Further reading

[edit]- Stevenson, David S. (2013). Under a crimson sun : prospects for life in a red dwarf system. New York, NY: Imprint: Springer. ISBN 978-1461481324.

External links

[edit]- "Red Dwarf Stars Probably Not Friendly for Earth 2.0". Seeker. 26 May 2015.