| Harlem Cultural Festival | |

|---|---|

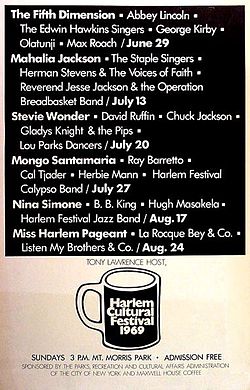

Poster for the 1969 festival | |

| Genre | Rock music, R&B, soul music, jazz, pop music, gospel |

| Dates | June 29 – August 24, 1969 |

| Location(s) | Mount Morris Park in Harlem Manhattan New York City |

| Founders | Tony Lawrence |

The Harlem Cultural Festival was a series of events, mainly music concerts, held annually in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, between 1967 and 1969 which celebrated soul, jazz and gospel and black music and culture and promoted Black pride. The most successful series of concerts, in 1969, became known informally as Black Woodstock,[1] and is presented in the 2021 documentary film Summer of Soul.

Although the 1968 and 1969 events were filmed by Hal Tulchin, the festival had difficulty gaining publicity, partially due to lack of interest by television networks, which felt there would be little benefit in broadcasting it. What was filmed was stored in a basement and hidden from history for decades.[2] The 1969 event took place around the same time as the Woodstock festival, which may have drawn media attention away from Harlem.

Origins and early festivals

[edit]A Harlem Cultural Festival was first proposed in 1964 to bring life to the Harlem neighborhood.[3] At the same time, in the mid-1960s, nightclub singer Tony Lawrence began working on community initiatives in Harlem, initially for local churches, but from 1966 working under New York City Mayor John Lindsay and Parks Commissioner August Heckscher. In 1967, Lawrence helped set up the first Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of free events held across Harlem that included "a Harlem Hollywood Night, boxing demonstrations, a fashion show, go-kart grand prix, the first Miss Harlem contest, and concerts featuring soul, gospel, calypso, and Puerto Rican music".[4][5] In 1968, the second annual Festival included a series of music concerts featuring high profile figures, including Count Basie, Bobby "Blue" Bland, Tito Puente, and Mahalia Jackson.[4] It was filmed by documentary maker Hal Tulchin, and excerpts were broadcast on WNEW-TV in New York.[6]

1969 Harlem Cultural Festival

[edit]Lawrence also hosted and directed the 1969 festival, held in Mount Morris Park on Sundays at 3 PM from June 29 to August 24, 1969. Sponsors included Maxwell House Coffee, and what was then the Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Affairs Division of the City of New York (later separated into Parks and Recreation and Cultural Affairs).[7] Lawrence secured a wide range of performers including Nina Simone, B.B. King, Sly and the Family Stone, Chuck Jackson, Abbey Lincoln & Max Roach, the 5th Dimension, David Ruffin, Hugh Masakela, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson, Mongo Santamaria, Ray Barretto, and Moms Mabley, among many others. The Woodstock rock festival also took place in August 1969, and the Harlem festival then became known informally as the "Black Woodstock".[8][9]

The Festival also involved the participation of community activists and civic leaders including Jesse Jackson.[10] The series of six free concerts had a combined attendance of nearly 300,000.[4] For the concert featuring Sly and the Family Stone on June 29, 1969, the New York City Police Department (NYPD) refused to provide security, and it was instead provided by members of the Black Panther Party.[7]

Film maker Hal Tulchin used five portable video cameras to record over 40 hours of footage of the Festival.[11] Although the majority of this video remains commercially unreleased, CBS broadcast a one-hour special on July 28, 1969, featuring the 5th Dimension, The Chambers Brothers, and Max Roach with Abbey Lincoln. A second hour-long special followed on September 16 on ABC, featuring Mahalia Jackson, the Staple Singers, and Reverend Jesse Jackson.[6] A further five TV specials were announced at the time, but do not appear to have been broadcast.[3]

Summer of Soul

[edit]Several attempts were made to turn Hal Tulchin's videos into a television special or film, including one by Tulchin in 1969 and another in 2004 that ended when funding ran out. During this period, Tulchin named the project Black Woodstock in the hope of gaining further interest.[3] In 2019, it was announced in numerous outlets that Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson would make his directorial debut with Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), a feature documentary about the Harlem Cultural Festival. Questlove's film was released on July 2, 2021, in theaters and on Hulu to critical acclaim.[12][13][14][15] According to Metacritic, which assigned a weighted average score of 96 out of 100 based on 38 critics, the film received "universal acclaim".[16][17][18] On March 27, 2022, Summer of Soul won the Best Documentary award at the 94th Academy Awards.

50th anniversary festival

[edit]A 50th Year Anniversary celebration of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival took place August 14–17, 2019, in Harlem, hosted by Future x Sounds and City Parks Foundation Summerstage.[4][19] The event featured musical performances by Talib Kweli, Cory Henry, Alice Smith, Georgia Anne Muldrow, Keyon Harrold, Braxton Cook, Freddie Stone (who performed at the original event), George "Spanky" McCurdy, Nate Jones On Bass, was curated and co-produced by Neal Ludevig and was musically directed by Igmar Thomas.[20] The event also featured conversations with Jamal Joseph, Felipe Luciano, Gale Brewer, Toni Blackman, Juma Sultan, and Voza Rivers, among many others, at Harlem Stage and the Schomburg.[21][22]

Proposed later events

[edit]Tony Lawrence made plans for further festivals, aiming to turn the Harlem festival into an international touring enterprise, and made recordings aimed at promoting the festivals.[6] However, a shortage of funding meant that the plans failed to materialize. In 1972, Lawrence made a series of allegations in the Amsterdam News against two of his former legal and business partners, claiming financial irregularities. He took legal action against them for fraud, and also claimed that an attempt had been made on his life and that it remained under threat from the Mafia. The Amsterdam News noted that Lawrence's claims were unsubstantiated, and, at the urging of Shirley Chisholm and Charles Rangel, the legal action was dropped.[4] Lawrence also made claims against Tulchin over ownership of the recordings, and attempted to set up his own film company, Uganda Productions.[6] Lawrence attempted to organize further, smaller, versions of the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1973 and 1974, and to set up an International Harlem Cultural Festival, but the plans did not proceed.[4][6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Greene, Bryan (June 2017). "This Green and Pleasant Land". Poverty and Race Research Action Council.

- ^ "Summer of Soul: rescuing a lost festival from Woodstock's unlovely shadow". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- ^ a b c Gaunt, James (2022). "Summer of Soul". Rhythms Magazine (309): 66–69.

- ^ a b c d e f Bernstein, Jonathan (2019-08-09). "This 1969 Music Fest Has Been Called 'Black Woodstock.' Why Doesn't Anyone Remember?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- ^ Edwards, Eve (3 July 2021). "Who is Tony Lawrence? Summer of Soul explores Harlem Cultural Festival promoter's work". The Focus. GRV Media. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Gaunt, James (2021-12-21). "Who Is Tony Lawrence?". The Shadow Knows. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ a b Morgan, Richard (February 1, 2007). "The Story Behind the Harlem Cultural Festival Featured in 'Summer of Soul'". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- ^ "Summer of Soul: New film revives lost 'Black Woodstock' gig series". BBC News. 13 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Remembering Harlem's 'Black Woodstock'". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. August 15, 2009.

- ^ "Questlove's "Summer of Soul" Pulses with Long-Silenced Beats". The New Yorker. 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (September 14, 2017). "Hal Tulchin, Who Documented a 'Black Woodstock,' Dies at 90". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Lang, Brent (2019-12-02). "Questlove to Make Directorial Debut With 'Black Woodstock' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Shaffer, Claire (2019-12-02). "Questlove to Make Directorial Debut With 'Black Woodstock'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Saponara, Michael (2019-12-02). "Questlove to Direct 'Black Woodstock' Documentary". Billboard. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ "Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (2021)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Fear, David (2021-01-29). "'Summer of Soul' Is the Perfect Movie to Kick Off Sundance 2021". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan (2021-01-29). "Summer of Soul review – thrilling documentary reveals a forgotten festival". the Guardian. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- ^ Brooks, Daphne A. (2019-08-15). "At 'Black Woodstock,' an All-Star Lineup Delivered Joy and Renewal to 300,000". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- ^ "Marcus Garvey Park Events - Black Woodstock 50th Anniversary: Igmar Thomas / Talib Kweli / Keyon Harrold & Special Guests In association with Moon31 / Future Sounds : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Archived from the original on 2019-08-27. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- ^ "Changing communities, Black Woodstock, Black Panthers, and Activism". Global Soul Events, Music, News. Archived from the original on 2019-08-27. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- ^ "Dive Deeper: Black Woodstock 50th Anniversary Celebration". Harlem Stage. 15 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

Further reading

[edit]- "Parks and Recreation: Harlem at a Crossroads in the Summer of '69". Poverty & Race. Poverty and Race Research Action Council. June 2017.