Highland Park | |

|---|---|

Arroyo Seco Bank on Figueroa | |

| Coordinates: 34°06′43″N 118°11′53″W / 34.11194°N 118.19806°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| City | Los Angeles |

| Government | |

| • City Council | Eunisses Hernandez (D) Kevin de Leon (D) |

| • State Assembly | Wendy Carrillo (D) |

| • State Senate | María Elena Durazo (D) |

| • US Senators | Alex Padilla (D) Laphonza Butler (D) |

| • U.S. House | Jimmy Gomez (D) |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.4 sq mi (9 km2) |

| Elevation | 591 ft (180 m) |

| Population (2000)[1] | |

• Total | 57,566 |

| • Density | 16,809/sq mi (6,490/km2) |

| Population changes significantly depending on areas included and recent growth. | |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 90041–90042 |

| Area code | 213/323 |

Highland Park is a neighborhood in Los Angeles, California, located in the city's Northeast region. It was one of the first subdivisions of Los Angeles[3] and is inhabited by a variety of ethnic and socioeconomic groups.

History

[edit]

The area was settled thousands of years ago by Paleo-Indians, and would later be settled by the Kizh.[4] After the founding of Los Angeles in 1781, the Corporal of the Guard at the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, Jose Maria Verdugo, was granted the 36,403 acre Rancho San Rafael which included present day Highland Park. Drought in the mid-19th century resulted in economic hardship for the Verdugo family, which eventually compelled them to auction off Rancho San Rafael in 1869 for $3,500 over an unpaid loan. The San Rafael tract was purchased by Andrew Glassell and Albert J. Chapman, who leased it out to sheep herders. In 1885, during the 1880s land boom, it was sold to George Morgan and Albert Judson, who combined it with other parcels they had purchased from the Verdugo family to create the Highland Park tract in 1886.[5][3] Two rail lines were built to Highland Park, which later helped the town to survive the burst of the property bubble.[3] Highland Park was annexed to Los Angeles in 1895. In the early 20th century, Highland Park and neighboring Pasadena became enclaves for artists and intellectuals who were adherents of the Arts and Crafts movement.[6]

With the completion of Arroyo Seco Parkway in 1940, Highland Park began to experience white flight, losing residents to the Mid-Wilshire district and newer neighborhoods in Temple City and in the San Fernando Valley.[7] By the mid-1960s, it was becoming a largely Latino district. Mexican immigrants and their American-born children began owning and renting in Highland Park, with its schools and parks becoming places where residents debated over how to fight discrimination and advance civil rights.[8]

In the final decades of the 20th century, portions of Highland Park suffered waves of gang violence as a consequence of the Avenues street gang claiming them and the adjacent neighborhood of Glassell Park as its territory. At the beginning of the 21st century, then-City Attorney Rocky Delgadillo, a Highland Park native, intensified efforts to rid Northeast Los Angeles of the Avenues. In 2006, four members of the gang were convicted of violating federal hate crime laws.[9] In June 2009, police launched a major raid against the gang, rooting out many leaders of the gang with a federal racketeering indictment,[10] demolishing the gang's Glassell Park stronghold.[11] Law enforcement, coupled with community awareness efforts such as the annual Peace in the Northeast March, have led to a drastic decrease in violent crime in the 2010s.

In the early 2000s, relatively low rents and home prices, as well as Highland Park's pedestrian-friendly streets and proximity to Downtown Los Angeles attracted people of greater affluence than had previously been typical,[12][13] as well as a reversal of the white flight from previous decades.[14] Of special interest were the district's surviving Craftsman homes.[15] Similar to Echo Park and Eagle Rock, Highland Park has experienced rapid gentrification.[16][17][18] The topic of Highland Park's rapid neighborhood changes has garnered national and international attention.[19][20]

In the 2010s, Highland Park experienced significant job growth, especially with businesses along Figueroa Street and York Boulevard. Its educational, health, and social service careers also developed robustly during this period. However, most workers employed in Highland Park do not live there but commute from surrounding areas instead.[21] The benefits of Highland Park's 21st century economic revitalization have been experienced unevenly, bypassing many of the area’s longtime Latino residents.[22]

Geography and climate

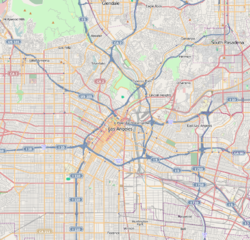

[edit]Highland Park’s boundaries are roughly the Arroyo Seco Parkway (California Route 110) on the southeast, Pasadena on the northeast, Oak Grove Drive on the north, South Pasadena on the east, and Avenue 51 on the west. Primary thoroughfares include York Boulevard and Figueroa Street.[23]

Highland Park sits within the Northeast Los Angeles region along with Mount Washington, Cypress Park, Glassell Park, and Eagle Rock.

| Climate data for Highland Park, Los Angeles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

70 (21) |

71 (22) |

75 (24) |

77 (25) |

83 (28) |

88 (31) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

82 (28) |

74 (23) |

69 (21) |

78 (26) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 45 (7) |

47 (8) |

48 (9) |

51 (11) |

55 (13) |

59 (15) |

62 (17) |

63 (17) |

61 (16) |

56 (13) |

49 (9) |

45 (7) |

53 (12) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.94 (100) |

4.39 (112) |

3.79 (96) |

1.00 (25) |

0.35 (8.9) |

0.14 (3.6) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.15 (3.8) |

0.39 (9.9) |

0.59 (15) |

1.33 (34) |

2.18 (55) |

18.29 (465) |

| Source: [24] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

The 2000 U.S. census counted 56,566 residents in the 3.42-square-mile neighborhood—an average of 16,835 people per square mile. In 2008, the city estimated that the population had increased to 60,841. The median age for residents was 28.[25]

The ethnic composition of Highland Park in 2000 was 72.4% Latino, 11.3% Non-Hispanic White, 11.2% Asian, 8.4% Black, and others, 2.6%. Among the 45% of residents born abroad, Mexico and El Salvador were the most common countries of origin. Mexican and German were the most common ancestries.[25]

The median household income in 2008 dollars was $45,478, and 59% of households earned $40,000 or less. The average household size was 3.3 people. Renters occupied 60.9% of the housing units.[25]

The percentage of never-married men was 41%. The 2000 census found that 21% of families were headed by single parents. There were 1,942 military veterans in 2000, or 4.9% of the population.[25]

According to the 2020 United States census, the ethnic composition of Highland Park in 2020 was 58.7% Latino, 21.8% Non-Hispanic White, 13.4% Asian, 1.8% Black, and 4.3% others. Overall, the population of Highland Park decreased by 7% between 2010 and 2020.[26][27]

Government and infrastructure

[edit]- The Highland Park Post Office - 5930 North Figueroa Street.[28]

- Los Angeles Fire Department Station 12 - 5921 North Figueroa Street.[29]

Transportation

[edit]

- The A Line - The Highland Park Station is located at the intersection of North Avenue 57 at Marmion Way. Built upon the same site as another rail station which was demolished in 1965, the new Highland Park Station was opened in 2003 as part of the original Gold Line.

- Metro Local bus lines 81, 182 & 256 connect to the surrounding areas of Pasadena, South Pasadena, the San Gabriel Valley, and Downtown Los Angeles

- LADOT's DASH Highland Park/Eagle Rock bus line begins in San Pascual Park and ends near the city limits with Glendale. The route connects several local schools, shopping districts, and the Eagle Rock Plaza.

- Arroyo Seco Parkway (California State Route 110) - formerly known as the Pasadena Freeway, it runs through Highland Park and has served local commuters since it opened in 1940.

Parks and libraries

[edit]- Highland Park Recreation Center - 6150 Piedmont Avenue.[30]

- York Boulevard Park - 4948 York Boulevard.[31]

- Sycamore Grove Park - 4702 N. Figueroa St.[32]

- Hermon Park/Arroyo Seco Park - 5566 Via Marisol.[33]

- Garvanza Park - 6240 Meridian St.[34]

- Arroyo Seco Regional Library - 6145 N Figueroa Street. It is a branch of Los Angeles Public Library.[35]

Highland Park was served by a series of public libraries starting in 1890. It housed a collection of 50 books at the now demolished Miller's Hall, formerly located on York Boulevard between Avenues 63 and 64. As the library's collection grew, it was moved to other locations along nearby Avenue 64 in order to accommodate. A grant from Andrew Carnegie made possible a purpose-built facility which eventually became the original Arroyo Seco Library.[36] Its location was decided upon in 1911 as a compromise between the competing residential centers of the district, as well in order to adhere to the stipulations of the grant.[37] The library was opened in 1914.[36]

On October 17, 1960, a newly constructed Arroyo Seco Library was opened to the public, replacing the original building after 46 years of service. Designed by architect John Landon, the second Arroyo Seco Library was the base of operations for the entire northeast region of the Los Angeles Public Library system. It also was equipped with rooftop parking which had access to the library's front door, a feature that was first of its kind among public libraries in the United States.[38] This building would itself be replaced by another, modernized facility in 2003.[39]

Religion

[edit]Highland Park is home to a wide array of religious practitioners. The St. Ignatius Church has been the house of worship for followers of Roman Catholicism in the district since the early 20th century. Originally located on Avenue 52, the church was moved to its present location on the corner of Avenue 60 and Monte Vista Street in 1915.[40]

Temple Beth Israel of Highland Park and Eagle Rock was founded in Highland Park in 1923 and constructed its building in 1930. It is the second oldest synagogue in Los Angeles still operating in its original location, after the Wilshire Boulevard Temple (built in 1929).[41][42]

Landmarks and attractions

[edit]- Galco's Soda Pop Stop has been owned and operated by the Nese family for more than a century.[43]

- Avenue 50 Studio, a nonprofit community-based organization grounded in Latino and Chicano culture.[44]

- Tierra de la Culebra Park, a public art park.[45]

- Pisgah Home Historic District - added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.[46]

Historic-Cultural Monuments

[edit]The following Historic-Cultural Monuments are located in Highland Park:

- Charles Lummis Residence, 200 E. Avenue 43. Historic-Cultural Monument #68, 1970

- Hiner House, 757 N. Figueroa Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #105, 1972

- San Encino Abbey, 6211 Arroyo Glen. Historic-Cultural Monument #106, 1972

- El Mio, 5905 El Mio Drive, Historic-Cultural Monument #142, 1975

- Stroh Residnce, 6028 Hayes Avenue, Historic-Cultural Monument #143, 1975

- Highland Park Police Station, 6045 York Boulevard. Historic-Cultural Monument #274, 1984

- Highland Park Masonic Temple, 104 N. Avenue 56. Historic-Cultural Monument #282, 1984

- Ebell Club Building, 125-135 S. Avenue 57. Historic-Cultural Monument #284, 1984

- Yoakum House, 140-154 S. Avenue 59. Historic-Cultural Monument #287, 1985

- Drake House, 210-220 S. Avenue 60. Historic-Cultural Monument #338, 1988

- Santa Fe Arroyo Seco Railroad Bridge, 162 S. Avenue 61. Historic-Cultural Monument #339, 1988

- Sunrise Court, 5721-5729 Monte Vista Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #400, 1988

- Ziegler Estate, 4601 N. Figueroa Boulevard. Historic-Cultural Monument #416, 1989

- Ivar I. Phillips Dwelling, 4200 N. Figueroa Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #469, 1989

- Ivar I. Phillips Residence, 4204 N. Figueroa Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #470, 1989

- Arroyo Seco Bank Building, 6301-6311 N. Figueroa Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #492, 1990

- Casa de Adobe, 4603-4613 Figueroa Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #493, 1990

- Kelman Residence and Carriage Barn, 5029 Echo Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #494, 1990

- J.E. Maxwell Residence, 211 S. Avenue 52. Historic-Cultural Monument #539, 1991

- Reverend Williel Thomson Residence, 215 S. Avenue 52. Historic-Cultural Monument #541, 1991

- Department of Water and Power Distributing Station No. 2, 211-235 N. Avenue 61. Historic-Cultural Monument #558, 1992

- E.A. Spencer Estate, 5660 Ash Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #564, 1992

- Security Trust and Savings Bank, 5601 N. Figueroa Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #575, 1993

- York Boulevard State Bank, 1301-1313 N. Avenue 51. Historic-Cultural Monument #581, 1993

- W.F. Poor Residence, 120 N. Avenue 54. Historic-Cultural Monument #582, 1993

- Occidental College Hall of Letters Building (Savoy Apartments), 121 N. Avenue 50. Historic-Cultural Monument #585, 1993

- Murdock Residence, 4219 N. Figueroa Street. Historic-Cultural Monument #780, 2004

- Mills Cottage, 4746 Toland Way. Historic-Cultural Monument #781, 2004

- Wilkins House, 915 North Avenue 57. Historic-Cultural Monument #877, 2007

- York Boulevard Church of Christ, 4908 York Boulevard. Historic Cultural Monument #1071, 2015

- Coughlin House, 1501 Nolden Street. Historic Cultural Monument #1107, 2016

- Centro de Arte Publico, 5605-5607 N. Figueroa Street. Historic Cultural Monument #1233, 2021[47]

- Mexicano Art Center, 5337-41 N. Figueroa Street. Historic Cultural Monument #1234, 2021

- Mexico-Tenochitlan: The Wall that Talks, 100-120 N. Avenue 61 & 6029 N. Figueroa St. Historic Cultural Monument #1279, 2023

Education

[edit]Highland Park is zoned to the following schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District.[48]

Zoned elementary schools include:

- Aldama Elementary School

- Annandale Elementary School

- Buchanan Elementary School

- Bushnell Way Elementary School[49]

- Garvanza Elementary School

- San Pascual Elementary School

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola School (K-8)

- Toland Way Elementary School

- Yorkdale Elementary School

- Monte Vista Elementary School

- Arroyo Seco Museum Science Magnet School (K-8)

Residents are zoned to Luther Burbank Middle School[50] and Benjamin Franklin High School. Los Angeles International Charter High School and Academia Avance Charter also serve the community.

Notable people

[edit]- Isaac Colton Ash, City Council member, 1925–27[51]

- Maggie Baird, actress and screenwriter[52]

- Jackie Beat, drag performer and comedian[53]

- Beck, musician[54]

- Jackson Browne, musician[55]

- Rose La Monte Burcham (1857–1944), medical doctor and mining executive whose Highland Park house still stands[56]

- Zack de la Rocha, musician[57]

- Rocky Delgadillo, City Attorney of Los Angeles, 2001–2009[58]

- Daryl Gates, police chief from 1971 to 1992[59]

- Billie Eilish, musician, singer-songwriter[60]

- Che Flores, basketball referee[61]

- Edward Furlong, actor[62]

- John C. Holland, Los Angeles City Council member, 1943–67, businessman[63]

- Diane Keaton, Academy Award-winning actress, brought up in Highland Park [64]

- Mike Kelley, artist[65]

- Marc Maron, comedian and actor[66]

- Finneas O’Connell, singer-songwriter, record producer, musician, and actor[67]

- Ariel Pink, musician[68]

- Fritz Poock, artist[69]

- Cora Scott Pond Pope, real estate developer of the Mt. Angelus area of Highland Park[70]

- Skrillex, musician[71]

- Emily Wells, musician[72]

- David Weidman, silkscreen artist and animation background painter[73]

- Miles Heizer, actor[74]

- Marilyn Ferguson, New Age author and publisher

- Colm Tóibín, Irish novelist[75]

In popular culture

[edit]Motion pictures that have been shot in Highland Park include:

- Reservoir Dogs[76]

- The Lincoln Lawyer – location for the bar The York on York[77]

- Gangster Squad – In early 2012 the entire Highland Park downtown area along Figueroa Street was redone to look like post-WWII-era Los Angeles for the film.[78]

- Yes Man[79]

- Cyrus[80]

- Tuff Turf[81]

Television and feature films have used the old Los Angeles Police Department building in the 6000 block of York Boulevard.[82]

Smith Estate, an historic hilltop Victorian house, has been a shooting location for horror films such as Spider Baby, Silent Scream and Insidious: Chapter 2.

See also

[edit]- Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments on the East and Northeast Sides

- List of districts and neighborhoods of Los Angeles

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Los Angeles Times Neighborhood Project". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "Worldwide Elevation Finder".

- ^ a b c Los Angeles Department of City Planning, Highland Park-Garvanza Historic Preservation Overlay Zone (December 9, 2010). "4.1 History of Highland Park & Garvanza". Highland Park-Garvanza HPOZ Preservation Plan, Including Garvanza, Highland Park, Montecito Heights and Mount Angelus Neighborhoods (Report). Los Angeles Department of City Planning. pp. 17–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ https://www.cpp.edu/~tgyoung/Pom_Parks/Kizh%20not%20Tongva_9-27-17.pdf Archived February 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "The Highlands". Departures. Kcet.org. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Arroyo Culture". Departures. Kcet.org. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "The Parkway". Departures. Kcet.org. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Brown and Proud". Departures. Kcet.org. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ Mozingo, Joe; Quinones, Sam; Winton, Richard (February 23, 2008). "A gang's staying power". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Rubin, Joel (September 22, 2009). "Major police raid targets L.A.'s notorious Avenues gang". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Quinones, Sam (February 5, 2009). "Avenues gang bastion is demolished". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ McDonald, Kathy A. (June 18, 2008). "Edgy neighborhoods attract frosh buyers". Variety.

- ^ "Experience an alternative Los Angeles". London Evening Standard, February 22, 2012. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012.

- ^ Bogado, Aura (January 20, 2015). "Dispatch from Highland Park: Gentrification, Displacement and the Disappearance of Latino Businesses". Colorlines. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Lazo, Alejandro (March 11, 2012). "Highland Park becoming gentrified". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Logan, Tim (December 21, 2014). "Highland Park renters feel the squeeze of gentrification". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Juliano, Michael. "A guide to Highland Park". Timeout. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

Of all the neighborhoods in Northeast L.A.—if not the entire city—none have changed as rapidly as Highland Park.

- ^ Lin, Jan (June 4, 2015). "Northeast Los Angeles Gentrification in Comparative and Historical Context". KCET.

- ^ "York & Fig: At the Intersection of Change". Marketplace.org.

- ^ Gumbel, Andrew (January 26, 2020). "Whitewashed': how gentrification continues to erase LA's bold murals". The Guardian.

- ^ "The State of Highland Park" (PDF). Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ Kamin, Debra (October 22, 2019). "Highland Park, Los Angeles: A Watchful Eye on Gentrification". New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

But [Highland Park's] transition is complicated. Highland Park is historically Latino, and as housing prices have crept up, a slew of Spanish-speaking panaderias, bodegas, and businesses have shuttered.

- ^ Kamin, Debra (October 22, 2019). "Highland Park, Los Angeles: A Watchful Eye on Gentrification". New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "Zipcode 90042". www.plantmaps.com. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Highland Park Profile - Mapping L.A. - Los Angeles Times". Projects.latimes.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ Sanchez, Jesús (August 30, 2021). "2020 Census describes a shrinking Eastside". The Eastsider. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

In Highland Park, the population dropped 7% to nearly 51,000. Latinos accounted for 66% of the population—down 10% since 2010.

- ^ "American Community Survey - Census Data for 90042 Census Tract". US Census Bureau. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ "Post Office Location - HIGHLAND PARK." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on December 9, 2008.

- ^ "Los Angeles Fire Department — Fire Station 12". Lafd.org. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Highland Park Recreation Center". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. July 31, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "York Boulevard Park". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. July 19, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "Sycamore Grove Park". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. September 2, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ "Hermon Park". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. August 5, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ "Garvanza Park". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. August 13, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ "Arroyo Seco Regional Library". Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Dellquest, Wilfred (August 11, 1957). "Northeast Pictures: Arroyo Library result of sacrifice and determination" (PDF). Highland Park News-Herald and Journal. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Branch Library Location Pleases Some—Not All!". Highland Park News-Herald and Journal. September 23, 1911. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Public spirit builds library". Highland Park News-Herald and Journal. October 17, 1963. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Early Los Angeles Historical Buildings (1900 - 1925)". Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Catholics Erecting Huge Church Building". Highland Park News-Herald and Journal. October 9, 1915. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Leibowitz, Ed. "Finding Sanctuary". Archived from the original on September 16, 2008.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on April 29, 2009.

- ^ "GALCO'S SODA POP STOP | 7 Reinterpreting Highland Park | Departures". KCET. February 22, 1999. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Avenue 50 Studio | Art | Highland Park Field Guide". KCET. December 13, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Tierra De La Culebra: Park and Sculpture". KCET. November 20, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ "National Register Information System – Pisgah Historic District (#07001304)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ "Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments" (PDF). City of Los Angeles, Department of City Planning. June 3, 2022.

- ^ Susan Carrier (October 12, 2003). "History hopes to repeat itself in Highland Park". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ "You are about to leave the LAUSD Domain". Lausd.k12.ca.us. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Luther Burbank Middle School website". www.lbmsbears.com.

- ^ Los Angeles Public Library file

- ^ "The Highs and Lows of Being Billie Eilish". September 5, 2019.

- ^ O'Connor, Pauline (July 31, 2016). "Drag queen Jackie Beat's eye-popping pad is up for grabs". Curbed LA. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (February 20, 1994). "Don't Get Bitter on Us, Beck : Thanks to his rap-folk song 'Loser,' the 23-year-old musician is one of the hottest figures to emerge from the L.A. rock scene in years. But now that he's going national, how will he hold up under all the attention?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ "Sunday in the dungeon with Jackson Browne". The Eastsider LA. April 21, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ Bradford Caslon, "Rose La Monte Burcham -- 4900 Pasadena Avenue" A Look Back at Vintage Los Angeles (November 9, 2011).

- ^ "A Chicano Art Collective Needs Help Bringing This Massive Highland Park Mural Back to Life". Retrieved February 22, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Merl, Jean (July 1, 2001). "Life of Promise, Pressing New Issues". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Cannon, Lou (1998), Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD, p.92. Crown. ISBN 0-8129-2190-9. Excerpt available[permanent dead link] at Google Books.

- ^ "Get to Know: Billie Eilish". Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ Carmichael, Emma (October 23, 2023). "NBA Referee Che Flores on Becoming the First Out Trans and Nonbinary Ref in American Pro Sports". GQ. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ "Agreement Reached on Custody of Teen Actor". Los Angeles Times. September 27, 1991. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Los Angeles Public Library reference file

- ^ Finnigan, Kate (August 6, 2017). "Diane Keaton: Why I decided to adopt in my 50s". Glen Innes Examiner. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ "Highland Park pays tribute to Mike Kelley*". February 6, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ "Marc Maron Learned the Meaning of "Feral" from a Cat". August 6, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Powers, Ann (December 10, 2019). "Billie Eilish Is The Weird Achiever Of The Year". NPR. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ Samadder, Rhik (November 15, 2014). "Ariel Pink: 'I'm not that guy everyone hates'". The Guardian. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ "Fritz Poock's Water Colors". Los Angeles Times. July 2, 1933.

- ^ "Save the Date: Stairway tour explores history of Mt. Angelus one step at a time". The Eastsider LA. October 29, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Glazer, Joshua. "Skrillex: Strictly Laptop". Hot Topic. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011.

- ^ "The Evolution of Emily Wells, New York Phase". February 3, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Saperstein, Pat (August 7, 2014). "David Weidman, Animation Artist Whose Work Appeared on 'Mad Men,' Dies at 93". Variety. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ Berlinger, Max (February 21, 2020). "Connor Jessup of 'Locke & Key' Gets His Nails Done". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Max, D. T. (September 13, 2021). "How Colm Tóibín Burrowed Inside Thomas Mann's Head". The New Yorker.

- ^ "Film locations for Reservoir Dogs (1992)". Movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Highland Park bar gets a Hollywood close-up". The Eastsider LA. March 21, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Gangster Squad Recreates Mickey Cohen's 1940s LA - LA Plays Itself - Curbed LA". La.curbed.com. May 10, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Yes Man - Filming Locations - part 1". Seeing-stars.com. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Offbeat Rom-Com Cyrus Premieres at LA Film Festival". Blogcritics. June 19, 2010. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Tuff Turf (1985)". IMDb. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Tour Location: 6045 York Blvd, Los Angeles, California". The Movieland Directory. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

External links

[edit]- History of Highland Park—Occidental College Sociology Department article

- Audubon Center—Audubon Center at Debs Park

- Southwest Museum—Autry National Center, Southwest Museum of the American Indian

- Heritage Square Museum—Historic Rescued Homes

- York & Fig Archived February 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine—a reporting project by Marketplace on the gentrification of Highland Park

- laparks.org Highland Park bike route MAP