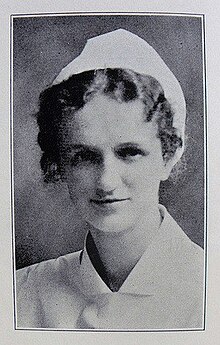

Hildegard Peplau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 1, 1909 Reading, Pennsylvania |

| Died | March 17, 1999 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Chestnut Lodge, Pottstown Hospital School of Nursing, Bennington College, Columbia University |

| Relatives | Letitia Anne Peplau (daughter) |

| Medical career | |

| Institutions | Army Nurse Corps, Rutgers University, World Health Organization |

Hildegard E. Peplau (September 1, 1909 – March 17, 1999)[1] was an American nurse and the first published nursing theorist since Florence Nightingale. She created the middle-range nursing theory of interpersonal relations, which helped to revolutionize the scholarly work of nurses. As a primary contributor to mental health law reform, she led the way towards humane treatment of patients with behavior and personality disorders.[2][3]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Hildegard was born in Reading, Pennsylvania to immigrant parents of German descent, Gustav and Otyllie Peplau. She was the second daughter born of six children. Gustav was an illiterate, hard-working father and Otyllie was an oppressive, perfectionist mother. Though higher education was never discussed at home, Hilda was strong-willed, with motivation and vision to grow beyond women's traditionally constructed roles. She wanted more out of life, and knew nursing was one of few career choices for women in her day.[1] As a child, she was watcher of people's behaviours. She witnessed the devastating flu epidemic of 1918, a personal experience that greatly influenced her understanding of the impact of illness and death on families.[1] She witnessed people jumping from windows in delirium caused by the flu.[4]

In the early 1900s, the autonomous, nursing-controlled, Nightingale era schools came to an end. Schools became controlled by hospitals, and formal "book learning" was discouraged. Hospitals and physicians saw women in nursing as a source of free or inexpensive labor. Exploitation was not uncommon by a nurse's employers, physicians, and educational providers.[5]

Career

[edit]

Peplau's entry into the nursing profession was not prompted by romantic notions of caring for the sick. In Reading, she completed courses at a business school and worked as a store clerk, payroll clerk, and book keeper while completing courses in a business school. She was the valedictorian of her evening high school class, graduating in 1928. Her choices, as she later described them, were "...marriage, teaching, or becoming a nun." By contrast, the prospect of "free room and board" in a nursing program made nursing an attractive choice.[1]

Peplau began her career in nursing in 1931 as a graduate of the Pottstown Hospital School of Nursing in Pottstown, Pennsylvania.[6] She then worked as a staff nurse in Pennsylvania and New York City. A summer position as nurse for the New York University summer camp led to a recommendation for Peplau to become the school nurse at Bennington College in Vermont. There she earned a bachelor's degree in interpersonal psychology in 1943.[6] At Bennington, and through field experiences at Chestnut Lodge, a private psychiatric facility, she studied psychological issues with Erich Fromm, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, and Harry Stack Sullivan. Peplau's lifelong work was largely focused on extending Sullivan's interpersonal theory for use in nursing practice.[7]

From 1943 to 1945, she served as a first lieutenant in the U. S. Army Nurse Corps,[6][8] and was assigned to the 312th Field Station Hospital in England, where the American School of Military Psychiatry was located. Here she met and worked with leading figures in British and American psychiatry. After the war, Peplau was at the table with many of these same men as they worked to reshape the mental health system in the United States through the passage of the National Mental Health Act of 1946.[1]

Peplau held master's and doctoral degrees from Teachers College, Columbia University.[6] She was also certified in psychoanalysis by the William Alanson White Institute of New York City.[6] In the early 1950s, Peplau developed and taught the first classes for graduate psychiatric nursing students at Teachers College. Dr. Peplau was a member of the faculty of the Rutgers College of Nursing now known as the Rutgers School of Nursing from 1954 to 1974. At Rutgers, Peplau created the first graduate level program for the preparation of clinical specialists in psychiatric nursing.[2][9]

She was a prolific writer, and was well known for her presentations, speeches, and clinical training workshops. Peplau was a tireless advocate for advanced education for psychiatric nurses. She thought that nurses should provide truly therapeutic care to patients, rather than the custodial care that was prevalent in the mental hospitals of that era. During the 1950s and 1960s, she conducted summer workshops for nurses throughout the United States, mostly in state psychiatric hospitals. In these seminars, she taught interpersonal concepts and interviewing techniques, as well as individual, family, and group therapy.

Peplau was an advisor to the World Health Organization, and was a visiting professor at universities in Africa, Latin America, Belgium, and throughout the United States. A strong advocate for research in nursing, she served as a consultant to the U.S. Surgeon General, the U.S. Air Force, and the National Institute of Mental Health. She participated in many government policy-making groups. She served as president of the American Nurses Association from 1970 to 1972, and as second vice president from 1972 to 1974.[10] After her retirement from Rutgers, she served as a visiting professor at the University of Leuven in Belgium in 1975 and 1976.[1]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Personal life

[edit]In 1944, Peplau met an American army psychiatrist who was also briefly stationed at the 312th Field Hospital in England. With the psychiatrist dealing with post combat stress, and Peplau herself unsettled by the unexpected death of her mother shortly after the couple met, their relationship quickly developed and Peplau became pregnant. However, since the psychiatrist was married to someone else, this relationship was a temporary one. Peplau went on to raise their daughter as a single parent. She rarely talked about the father to others, though she spoke highly of him shortly before her death. Letitia Anne Peplau was born in 1945, later grew up to become a psychology professor at UCLA, and an influential contributor to the scientific literature. After Letitia's birth, Peplau chose to have no more serious romances, and dedicated her time and energy to her daughter and her career.[1][11]

In 1999, Peplau died peacefully in her sleep at her home in Sherman Oaks, California.[12]

Theoretical work

[edit]In her interpersonal relationship theory, Dr. Peplau emphasized the nurse-client relationship, holding that this relationship was the foundation of nursing practice. Her book, Interpersonal Relations in Nursing, was completed in 1948.[13] Publication took four additional years, mainly because Peplau had authored a scholarly work without a coauthoring physician, which was unheard of for a nurse in the 1950s. At the time, her research and emphasis on the give-and-take of nurse-client relationships was seen by many as revolutionary. The essence of Peplau's theory was creation of a shared experience between nurse and client, as opposed to the client passively receiving treatment (and the nurse passively acting out doctor's orders). Nurses, she thought, could facilitate this through observation, description, formulation, interpretation, validation, and intervention. For example, as the nurse listens to her client she develops a general impression of the client's situation. The nurse then validates her inferences by checking with the client for accuracy. The result may be experiential learning, improved coping strategies and personal growth for both parties.

Peplau's model

[edit]Peplau's Six Nursing Roles

[edit]Peplau describes the six nursing roles that lead into the different phases:

- Stranger role: Peplau states that when the nurse and patient first meet, they are strangers to one another. Therefore, the patient should be treated with respect and courtesy, as anybody would expect to be treated. The nurse should not prejudge the patient or make assumptions about the patient, but take the patient as he or she is. The nurse should treat the patient as emotionally stable unless evidence states otherwise.

- Resource role: The nurse provides answers to questions primarily on health information. The resource person is also in charge of relaying information to the patient about the treatment plan. Usually the questions arise from larger problems, therefore the nurse would determine what type of response is appropriate for constructive learning. The nurse should provide straightforward answers when providing information on counseling.

- Teaching role: The teaching role is a role that is a combination of all roles. Peplau determined that there are two categories that the teaching role consists of: Instructional and experimental. The instructional consists of giving a wide variety of information that is given to the patients and experimental is using the experience of the learner as a starting point to later form products of learning which the patient makes about their experiences.

- Counseling role: Peplau believes that counselling has the biggest emphasis in psychiatric nursing. The counselor role helps the patient understand and remember what is going on and what is happening to them in current life situations. Also, to provide guidance and encouragement to make changes.

- Surrogate role: The patient is responsible for putting the nurse in the surrogate role. The nurse's behaviors and attitudes create a feeling tone for the patient that trigger feelings that were generated in a previous relationship. The nurse helps the patient recognize the similarities and differences between the nurse and the past relationship.

- Leadership role: Helps the patient assume maximum responsibility for meeting treatment goals in a mutually satisfying way. The nurse helps the patient meet these goals through cooperation and active participation with the nurse.[14]

Stages of the Nurse-Client Relationship

[edit]Orientation Phase

[edit]The orientation phase is initiated by the nurse. This is the phase during which the nurse and the patient become acquainted, and set the tone for their relationship, which will ultimately be patient centered. During this stage, it is important that a professional relationship is established, as opposed to a social relationship. This includes clarifying that the patient is the center of the relationship, and that all interactions are, and will be centered around helping the patient. This phase is usually progressed through during a highly impressionable phase in the nurse-client relationship, because the orientation phase occurs shortly after admission to a hospital, when the client is becoming accustomed to a new environment and new people. The nurse begins to know the patient as a unique individual, and the patient should sense that the nurse is genuinely interested in them. Trust begins to develop, and the client begins to understand their role, the nurse's role, and the parameters and boundaries of their relationship.

Identification Phase

[edit]The client begins to identify problems to be worked on within relationship. The goal of the nurse is to help the patient to recognize their own interdependent/participation role and promote responsibility for self.

Exploitation Phase / Working Phase

[edit]During the Working Phase, the nurse and the patient work to achieve the patient's full potential, and meet their goals for the relationship. A sign that the transition from the orientation phase to the working phase has been made, is if the patient can approach the nurse as a resource, instead of feeling a social obligation to the nurse (Peplau, 1997). The client fully trusts the nurse, and makes full use of the nurse's services and professional abilities. The nurse and the patient work towards discharge and termination goal.

Resolution Phase/Termination Phase

[edit]The termination phase of the nurse client relationship occurs after the current goals for the client have been met. The nurse and the client summarize and end their relationship. One of the key aspects of a nurse-client relationship, as opposed to a social relationship, is that it is temporary, and often of short duration (Peplau, 1997). In a more long-term relationship, termination can commonly occur when a patient is discharged from a hospital setting, or a patient dies. In more short-term relationships, such as a clinic visit, an emergency room visit, or a health bus vaccination visit, the termination occurs when the patient leaves, and the relationship is usually less complex. However, in most situations, the relationship should terminate once the client has established increased self-reliance to deal with their own problems.[15]

Works

[edit]- Peplau, Hildegard (1997). "Peplau's Theory of Interpersonal Relations". Nursing Science Quarterly. 10 (4). Chestnut House Publications: 162–167. doi:10.1177/089431849701000407. PMID 9416116. S2CID 1051540.

Awards

[edit]- 1997 - Christiane Reimann Award[16]

- 1994 - Living Legend of the American Academy of Nursing[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Callaway, B. J. (2002). Hildegard Peplau: Psychiatric nurse of the century, p. 3. New York: Springer.

- ^ a b O'Toole, A. W., & Welt, S. R. (Ed.). (1989). Interpersonal theory in nursing practice: Selected works of Hildegarde E. Peplau. New York: Springer.

- ^ Tomey, A. M., & Alligood, M. R. (2006). Nursing theorists and their work (6th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

- ^ Barker, P. (1999). Hildegard E Peplau: the mother of psychiatric nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 6, 175-176. Brock University Library Catalogue.

- ^ Chinn, P. L. (2008). Integrated theory and knowledge development in nursing (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

- ^ a b c d e "Hildegard E. Peplau papers, 1949-1987 PU- N.MC 59". Archives Space. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ Forchuk, C. (1993). Hildegarde E. Peplau: Interpersonal nursing theory – Notes on nursing theories (10). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- ^ "Peplau, Hildegard E. - Social Networks and Archival Context". snaccooperative.org. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ PhD, Barbara J. Callaway (2002-06-18). Hildegard Peplau: Psychiatric Nurse of the Century. Springer Publishing Company. pp. 294–317. ISBN 978-0-8261-9765-8.

- ^ Howk, C.(2002).Hildegard Peplau: Psychodynamic Nursing.In A, Tomey & M, Alligood(Eds.).Nursing Theorists and Their Work (5th ed. pp.379 - 382).St.Louis, MO: Mosby.

- ^ Christina Victor; Louise Mansfield; Tess Kay; Norma Daykin; Jack Lane; Lily Grigsby Duffy; Alan Tomlinson; Catherine Meads (October 2018). "An overview of reviews: the effectiveness of interventions to address loneliness at all stages of the life-course" (PDF). whatworkswellbeing.org. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Howk, C. (2002). Hildegard E. Peplau: Psychodynamic nursing. In A. Tomey & M. Alligood (Eds.), Nursing theory and their work (5th ed., pp. 379). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

- ^ Belcher, J. R., & Brittain-Fish, L. J., (2002). Interpersonal Relations in Nursing: Hildegard E. Peplau. In J. George (Ed.), Nursing theories: The base for professional nursing practice (5th ed.)(pp. 61-82). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- ^ Howk, C (1998). Hildegard E. Peplau: Psychodynamic Nursing. In A. Tomey & M. Alligood. Nursing Theorists and their Work (4th ed., pp. 338). St. Louis, Mosby.

- ^ Peterson, S. J., (2009). Interpersonal Relations. In S. Peterson & T. Bredow (Eds.), Middle range theories: Applications to nursing research (2nd Ed.)(pp. 202-230). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ "Christiane Reimann prize to be shared". Nursing Management. 3 (10): 6. March 1997. doi:10.7748/nm.3.10.6.s9. ISSN 1354-5760.

- ^ "Living Legends - American Academy of Nursing Main Site". www.aannet.org. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

External links

[edit]- Papers of Hildegard E. Peplau, 1923-1984. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Hildegard E. Peplau papers, 1949-1987 PUN.MC 59, University of Pennsylvania: Barbara Bates Center for the Study of The History of Nursing.