The history of education in New York City includes schools and schooling from the colonial era to the present. It includes public and private schools, as well as higher education. Annual city spending on public schools quadrupled from $250 million in 1946 to $1.1 billion in 1960. It reached $38 billion in 2022, or $38,000 per public school student.[1] For recent history see Education in New York City.

Colonial

[edit]There was limited public education during the British colonial period especially in the South and in rural areas.

Prior to the American Revolution, Columbia University, then called King’s College, was the only institution of higher education in New York City. It was one of 9 Colonial colleges founded before the Revolution.

1776 to 1898

[edit]New York was one of the last major cities to set up a public school system. State funds were available, but they were distributed to private organizations running private schools. Families that could afford it hired tutors for their children. In the early Republic, various elite societies emerged to promote education among marginal groups.[2]

The New York Manumission Society was established in 1785 by antislavery activists, including John Jay and Alexander Hamilton. Its stated goals were to alleviate the injustices of slavery, protect the rights of Blacks, and provide them with free educational opportunities. In 1787 it set up the African Free School. This school expanded over time, enrolling over 700 students by 1815. It received support from the city and the state.

In 1805 the Free School Society, organized by philanthropists, was chartered by the state legislature to teach poor children. It received grants from the city and the state and, starting in 1815, funding from the new State Common School Fund. By 1826 it was renamed the Public School Society and operated eight schools with 345 pupils, with separate departments for boys and girls. They were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and religion. Although a private organization, the Public School Society dominated the educational scene, enrolling thousands of pupils in a system that grew to 74 schools.

By 1834, its schools were integrated into the Public School Society.[3] In 1801, the city's Quakers formed the Association of Women Friends for the Relief of the Poor, hired an educated and moral widow as an instructor, and opened the first free school for poor white children. It grew to 750 students by 1823 and received some financial aid from the city or state.[4]

In 1853 the Free School Society became part of the new public school system when it was absorbed by the New York City Board of Education.[5]

In 1829 there were 43,000 children ages 5 to 15 in a city of 200,000. About half were poor and did not get any formal schooling. About 14,000 paid tuition to attend one of the many nonsectarian private schools. Some 4,000 attended church-sponsored schools, such as the Collegiate School, founded by the Dutch in 1628). And 5,000 attended public elementary schools. (There were no public high schools. Working-class youth who had some schooling seldom stayed after age 14, when they started work or became apprentices.[6] The "Free Academy of the City of New York", the first public high school, was established in 1847 by a wealthy businessman and president of the Board of Education Townsend Harris. It included both a high school and a college. There was no tuition; one goal was to provide access to a good education based on the student's merits alone. The conservative Whig Party denounced the school, while Tammany Hall and the Democrats endorsed the plan, and voters gave it 85% approval in a referendum. The Free Academy later dropped its high school and transformed into City College of New York. Other cities had moved much sooner to establish high schools: Boston (1829), Philadelphia (1838), and Baltimore (1839).[7][8]

The Catholic issue

[edit]The Catholic bishop of New York, John J. Hughes in 1840-1842 led a political battle to secure funding for the Catholic schools. He rallied support from both the Tammany Hall Democrats, and the opposition Whig Party, whose leaders, especially Governor William H. Seward supported Hughes. He argued Catholics paid double for schools—they paid taxes to subsidize private schools they could not use and also paid for the parochial schools they did use. Catholics could not use Public School Society schools because they forced students to listen to readings from the Protestant King James Bible which were designed to undermine their Catholic faith. With the Maclay Act in 1842, the New York State legislature established the New York City Board of Education. It gave the city an elective Board of Education empowered to build and supervise schools and distribute the education fund. It provided that no money should go to the schools that taught religion, so Hughes lost his battle.[9]

Parochial system

[edit]Bishop Hughes turned inward: he founded an independent Catholic school system in the city. His new system included the first Catholic college in the Northeast, St. John's College, now Fordham University.[10] By 1870 19 percent of the city's children were attending Catholic schools.[11][12]

Increasingly American-born Irish women attended high schools and normal schools in preparation for a teaching career. The supply allowed the diocese to create many new Catholic elementary schools. After 1870 20 percent of the teachers in the city's public schools were Irish.[13][14] Teaching "had status,” explained a teacher whose parents were immigrants from Ireland. “[You were] looked up to...like a doctor.”[15]

Many of the young immigrant or American-born women joined religious orders. French Catholic orders also established branches in the United States. The nuns were assigned to teach in parochial schools or to work in hospitals and orphanages.[16] One prominent leader was Mother Marie Joseph Butler (1860-1940), an Irish-born Catholic sister who dedicated her life to establishing schools and colleges. In the early 20th century she founded 14 schools, including Marymount School and College in Tarrytown, New York, a suburb of New York City. She established 14 schools, 3 of them colleges, in the United States. Her conviction of the educational value of international experience led her to establish the first study abroad program through Marymount College.[17]

Progressive era, 1890s to 1920s

[edit]By 1860, elementary teaching was a female role, especially in the Northeast with rates of 80% of more female in both urban and rural areas, reaching 89% statewide in New York in 1915. A high school education was the normal requirement. In 1860, about 90% were under age 30, and half were under 25.[18] By 1930, nearly all had started college and 22% had a college degree.[19]

Immigration from Eastern Europe soared after 1880, as did enrollments of Jews, Italians and others. Enrollment in the elementary schools soared from 250,000 in 1881 (including Brooklyn) to 494,000 in 1899, and 792,000 in 1914, when immigration ended. While the number of schools held steady at about 500, the number of teachers doubled from 9,300 in 1899 to 20,000 in 1914. High school enrollment soared from 14,000 in 1899 to 68,000 in 1914.[20] One immigrant from Germany in 1857 was Felix Adler (1851-1933). Adler returned to Germany for a PhD from Heidelberg University at a time only Harvard had a PhD program. He served as a professor of philosophy at Columbia University, 1902-1933. His Society for Ethical Culture promoted numerous educational reforms in the City. They founded a high school for gifted youth, and a teacher training school. They promoted vocational schools that taught basic manual trades. Adler was a national leader in the battle against child labor, and organized advanced studies of children.[21]

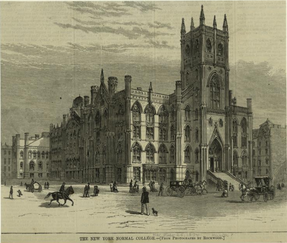

Hunter College was founded in 1870 as the Female Normal and High School, to train young women as teachers in elementary schools. The Industrial Education Association, formed in 1884, promoted manual training courses in the new high schools, and it emphasized the need for more advanced teacher training. It helped found a Teachers College, which became a unit of Columbia University in 1898. It gained a national and international reputation in pedagogy. John Dewey was a highly influential professor there from 1904 until 1930.[22][23] A smaller institution was the Bureau of Educational Experiments, an independent, graduate education school that opened in 1916 and became an experimental site for innovation under the leadership of Lucy Sprague Mitchell (1878–1967). It became the Bank Street College of Education in 1950.[24]

Conflict over the Gary Plan

[edit]In 1907, William Wirt became superintendent of schools in the newly planned city of Gary, Indiana, which was built by U.S. Steel corporation. Wirt began implementing his educational values in the local schools. He initiated teacher hiring standards, designed school buildings, lengthened the school day, and organized the schools according to his ideals. The core of the schools' organization in Gary centered upon the platoon or work-study-play system and Americanizing the 63.4 percent of children with parents who were immigrants.[25] The theory behind the Gary Plan was to accommodate children's shorter attention spans, and that long hours of quiet in the classroom were not tenable.[26]

Above the primary grades, students were divided into two platoons—one platoon used the academic classrooms (which were deemphasized), while the second platoon was divided between the shops, nature studies, auditorium, gymnasium, and outdoor facilities split between girls and boys.[25] Students spent only half of their school time in a conventional classroom.[26] "Girls learned cooking, sewing, and bookkeeping while the boys learning metalwork, cabinetry, woodworking, painting, printing, shoemaking, and plumbing."[25] In the Gary plan, all of the school equipment remained in use during the entire school day; Rather than opening up new schools for the overwhelming population of students, it was hoped that the "Gary Plan would save the city money by utilizing all rooms in existing schools by rotating children through classrooms, auditoriums, playgrounds, and gymnasiums."[25]

The platoon system gained acceptance in Gary and received national attention during the early decades of the twentieth century. In 1914, New York City hired Wirt as a part-time consultant to introduce the work-study-play system in the public schools. In the following three years, however, the Gary system encountered resistance from students, parents, and labor leaders concerned that the plan simply trained children to work in factories and the fact that Gary's Plan was in predominantly Jewish areas.[25] In part because of backing from the Rockefeller family, the plan became heavily identified with the interest of big business.[26] "In January 1916, the Board of Education released a report finding students attending Gary Plan schools performed worse than those in 'non-Garyuzed schools' ."[27]

Mayor John Purroy Mitchel was a reformer who wanted the Gary Plan on city schools. In 1914 there were 20,000 teachers handling 800,000 students in the city's public schools, which had a budget of $44 million. Mitchel argued the Gary Plan was ideal for the students and the community, and assured business it would lower costs since two platoons a day would use the buildings.[28] Fierce opposition by the unions and the Jewish community to the Gary Plan was a major factor in defeating Mitchel's bid for reelection in 1917.[26]

After 1917

[edit]Teachers organize

[edit]Two unions of New York schoolteachers, the Teachers Union, founded in 1916, and the Teachers Guild, founded in 1935, failed to gather widespread enrollment or support. Many of the early leaders were pacifists or socialists and so frequently met with clashes against more right-leaning newspapers and organizations of the time, as red-baiting was fairly common. The ethnically and ideologically diverse teachers associations of the city made the creation of a single organized body difficult, with each association continuing to vie for its own priorities irrespective of the others.[29]

United Federation of Teachers

[edit]The UFT was founded in 1960, largely in response to perceived unfairness in the educational system's treatment of teachers. Pensions were awarded to retired teachers only if over 65 or with 35 years of service. Female teachers faced two years of mandatory unpaid maternity leave after they gave birth. Principals could discipline or fire teachers with almost no oversight. The schools, experiencing a massive influx of baby boomer students, often were on double or triple sessions. Despite being college-educated professionals, often holding advanced master's degrees, teachers drew a salary of $66 per week, or in 2005 dollars, the equivalent of $21,000 a year.

The UFT was created on March 16, 1960, and grew rapidly. On November 7, 1960, the union organized a major strike. The strike largely failed in its main objectives but obtained some concessions, as well as bringing much popular attention to the union. After much further negotiation, the UFT was chosen as the collective bargaining organization for all city teachers in December 1961.[30]

Albert Shanker, a controversial but successful organizer was president of the UFT from 1964 until 1984. He held an overlapping tenure as president of the national American Federation of Teachers from 1974 to his death in 1997.

In 1968, the UFT went on strike and shut down the school system in May and then again from September to November to protest the decentralization plan that was being put in place to give more neighborhoods community control. The Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike focused on the Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn but, ironically, the schools in that area were among the few that were open in the entire city. The Ocean Hill-Brownsville crisis is often described as a turning point in the history of unionism and of civil rights, as it created a rift between African-Americans and the Jewish communities, two groups that were previously viewed as allied. The two sides threw accusations of racism and anti-Semitism at each other.

Following the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis, some 14,000 teachers were laid off and class size soared. Another strike addressed some of these complaints and gave long-serving teachers longevity benefits.

See also

[edit]- New York City Department of Education

- New York City Schools Chancellor § List of New York City Schools chancellors

- List of schools in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York

- New York Interschool, elite private schools in Manhattan.

- Teachers College, Columbia University

- Council of School Supervisors & Administrators: trade union representing supervisors in NYC schools

- Teachers Union (1916–1964)

- Teachers Guild (1935–1960). merged into UFT

- United Federation of Teachers (UFT, 1960 – present)

- American Federation of Teachers nationwide; UFT is member

- New York State United Teachers, statewide; UFT is member

- New York City teachers' strike of 1968, UFT responding to teachers fired in Ocean City-Brownsville

References

[edit]- ^ See Independent Budget Office of the City of New York, "Education Spending Since 1990" (2023)

- ^ Carl F. Kaestle, The Evolution of an Urban School System: New York City, 1750-1850 (1973) p. 75.

- ^ John L. Rury, "The New York African Free School, 1827-1836: Community Conflict over Community Control of Black Education," Phylon 44#3 (1983) pp. 187–197 online.

- ^ William H. S. Wood, Friends of the City of New York in the Nineteenth Century (1904) pp. 28-31.

- ^ William W. Cutler, "Status, values and the education of the poor: The trustees of the New York Public School Society, 1805-1853." American Quarterly 24.1 (1972): 69-85 online

- ^ Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, (1999), p. 501.

- ^ Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, (1999), p. 781.

- ^ Mario Emilio Cosenza, The Establishment of the College of the City of New York as the Free Academy in 1847 (1925) online

- ^ Martin L. Meenagh, Archbishop John Hughes and the New York Schools Controversy of 1840–43 American Nineteenth Century History (2004) 5#1, pp. 34-65, 10.1080/1466465042000222204 online Archived 2013-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schroth, Raymond A. (2008). Fordham: A History and Memoir (rev. ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8232-2977-2. OCLC 727645703.

- ^ Ravitch (1975) pp 3–76.

- ^ Joseph McCadden, "New York's School Crisis of 1840–1842: Its Irish Antecedents." Thought: Fordham University Quarterly 41.4 (1966): 561-588.

- ^ Hasia Diner, Erin's Daughters in America: Irish Immigrant Women in the Nineteenth Century (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983) pp. 96-99.

- ^ Ravitch, p. 102

- ^ Quoted in Janet A. Nolan, Ourselves Alone: Women's Emigration from Ireland, 1885-1920 (University Press of Kentucky, 2021) ch. 5.

- ^ George C. Stewart, Marvels of charity: History of American sisters and nuns (1994) pp.174–180.

- ^ Kathleen A. Mahoney, "Butler, Mother Marie Joseph" in American National Biography (1999).

- ^ Joel Perlmann, and Robert A. Margo, Women’s Work? American Schoolteachers, 1650-1920 (U of Chicago Press, 2001) pp. 22, 37, 90.

- ^ Edward S. Evenden, et al. National Survey of Education of the Education of Teachers. Bulletin, 1933, No. 10. Volume 2: Teacher Personnel in the United States (Office of Education, United States Department of the Interior, 1935) p. 46-47

- ^ Berrol pp 145-146.

- ^ Ellen Salzman-Fiske, Secular religion and social reform: Felix Adler's educational ideas and programs, 1876-1933 (Columbia University Press, 1999).

- ^ Ravitch, The Great School Wars p. 112.

- ^ F. M. McMurry, et al. "Theory and practice at Teachers College, Columbia University." Teachers College Record 5.6 (1904): 43-64. online

- ^ Patricia Fisher, and Anne Perryman, A brief history: Bank Street College of Education (2000) online.

- ^ a b c d e Weiner, 2010, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Ballard, Adele M. (November 24, 1917). "The Gary Bugaboo". The Town Crier. Vol. 12, no. 47. Seattle. p. 8. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ Weiner, 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Raymond A. Mohl, "Schools, Politics, and Riots: The Gary Plan in New York City, 1914-1917," Paedagogica Historica 15.1 (1975): 39-72.

- ^ A different kind of teachers union. Review by Peter Lamphere and Gina Sartori. International Socialist Review. Issue #80. November 2011. Review of: Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union by Clarence Taylor. Columbia University Press, 2011.

- ^ Levine, Marvin J. (1970). "The Issues in Teacher Strikes". The Journal of General Education. 22 (1): 1–18. ISSN 0021-3667. JSTOR 27796193.

Further reading

[edit]- Berrol, Selma. "Immigrants at School: New York City, 1900-1910." Urban education 4.3 (1969): 220–230. online

- Berrol, Selma Cantor. "Immigrants at School: New York City, 1898-1914" (PhD dissertation, City University of New York; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1967. 6712555).

- Berrol, Selma C. "William Henry Maxwell and a New Educational New York." History of Education Quarterly 8.2 (1968): 215–228. online

- Bourne, William Oland. History of the Public School Society of the City of New York: with portraits of the presidents of the Society (1870) online

- Browne, Henry. "Public Support of Catholic Education in New York 1825–1842; Some New Aspects" Catholic Historical Review 39 (1953), pp. 1–27

- Brumberg, Stephan F. Going to America, Going to School: The Jewish Immigrant Public School Encounter in Turn-of-the-Century New York City (Praeger, 1986); 1982 75 page version, online

- Burfield, Elizabeth. "History of Public Elementary Education in Staten Island, New York" (MA thesis, Fordham University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1948. 28927811).

- Burrows, Edwin G., and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (Oxford UP, 1999).

- Cohen, Sol. Progressives and Urban School Reform: The Public Education Association of New York City 1895-1954 (1964)

- Commission on Educational Reconstruction. Organizing the Teaching Profession: The Story of the American Federation of Teachers (1955)

- Cutler, William W. “Status, Values and the Education of the Poor: The Trustees of the New York Public School Society, 1805-1853.” American Quarterly 24#1 (1972), pp. 69–85. online

- Edgell, Derek. The Movement for Community Control of New York City's Schools, 1966–1970: Class Wars, (Edwin Mellen Press, 1998). 532pp.

- Fass, Paula S. Outside in: Minorities and the transformation of American education. Oxford University Press, 1991; see ch.3, "'Americanizing' the High Schools: New York in the 1930s and '40s," pp 73–111.

- Gifford, Walter John. Historical development of the New York State high school system (1922) online

- Hammack, David C. Power and society: greater New York at the turn of the century (1982) online pp. 258–299 on 1890s.

- Huberman, Michael. "The professional life cycle of teachers." Teachers College Record 91.1 (1989): 31-57. online

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. The Encyclopedia of New York City (2010)

- Jeynes, William H. "Immigration in the United States and the golden years of education: Was Ravitch right?." Educational Studies 35.3 (2004). online

- Justice, Benjamin. "Thomas Nast and the Public School of the 1870s" History of Education Quarterly 45#2 (2005), pp. 171–206. online includes analysis of his cartoons and copies of several

- Kaestle, Carl F. The Evolution of an Urban School System: New York City, 1750-1850 (Harvard UP, 1973) online

- Kilpatrick, William Heard. The Dutch schools of New Netherland and colonial New York (1912) online

- Klepper, Rachel. "School and Community in the All-Day Neighborhood Schools of New York City, 1936-1971." History of Education Quarterly 63.1 (2023): 107–125.

- Lannis, Vincent P. Public Money and Parochial Education: Bishop Hughes, Governor Seward, and the New York Schools Controversy (Case Western Reserve University Press, 1968)

- Lewis, Heather. New York City public schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community control and its legacy (Teachers College Press, 2015) online

- McAvoy, Thomas T. "Public Schools vs. Catholic Schools and James McMaster," Review of Politics (1966) 28#1 pp. 19–46 [1] James McMaster edited the leading Catholic newspaper in NYC.

- Meenagh, Martin L. "Archbishop John Hughes and the New York Schools Controversy of 1840–43." American Nineteenth Century History 5.1 (2004): 34-65. online

- Ment, David. "Patterns of public school segregation, 1900-1940: A comparative study of New York City, New Rochelle, and New Haven." in Schools in cities: Consensus and conflict in American educational history (1983): 67–110.

- Mohl, Raymond A. "Schools, Politics and Riots: The Gary Plan in New York CIty, 1914-1917," Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education 15.1 (1975): 39-72. online

- Pantoja, Segundo. Religion and Education among Latinos in New York City (Brill, 2005).

- Ravitch, Diane. The great school wars: A history of the New York City public schools (1975), a standard scholarly history online

- Ravitch, Diane, and Joseph P. Viteritti, eds. City Schools: Lessons from New York (2000)

- Ravitch, Diane, ed. NYC schools under Bloomberg and Klein what parents, teachers and policymakers need to know (2009) essays by experts online

- Ravitch, Diane, and Ronald K. Goodenow, eds. Educating an Urban People: The New York City Experience (1981) online

- Reyes, Luis. "The Aspira consent decree: A thirtieth-anniversary retrospective of bilingual education in New York City." Harvard Educational Review 76.3 (2006): 369–400.

- Rogers, David. Mayoral control of the New York City schools (Springer Science & Business Media, 2009) online.

- Rousmaniere, Kate. City Teachers: Teaching and School Reform in Historical Perspective (1997) on NYC teachers in the 1920s online

- Ruis, Andrew R. " 'The Penny Lunch Has Spread Faster than the Measles': Children's Health and the Debate over School Lunches in New York City, 1908–1930." History of Education Quarterly 55.2 (2015): 190–217. online

- Shelton, Jon. "Dropping Dead: Teachers, the New York City Fiscal Crisis, and Austerity" in Shelton, Teacher Strike! Public Education and the Making of a New American Political Order (U of Illinois Press, 2017) pp 114–142.

- Taft, Philip. United they teach; the story of the United Federation of Teachers (1974) online

- Taylor, Clarence. Knocking at our own door: Milton A. Galamison and the struggle to integrate New York City schools (Lexington Books, 2001) online.

- Tyack, David, and Larry Cuban. Tinkering toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform (Harvard UP, 1997) onlne

- Tyack, David B. The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (Harvard UP, 1974). online

- Wallace, Mike. Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919 (2017), a standard scholarly history online

- Weiner, Melissa F. Power, protest, and the public schools: Jewish and African American struggles in New York City (Rutgers UP, 2010) online.

Primary sources

[edit]- Boese, Thomas, C. ed. Public education in the city of New York: its history, condition, and statistics : an official report to the Board of Education (1869) online

- Bruere, Henry. "Mayor Mitchel's administration of the city of New York." National Municipal Review 5 (1916): 24+ online.

- Department of Education of the City of New York.

- Fifth Annual report of the City Superintendent of Schools for the year ending 1902 online

- Evenden, Edward S., Guy C. Gamble, and Harold G. Blue. National Survey of Education of the Education of Teachers. Bulletin, 1933, No. 10. Volume 2: Teacher Personnel in the United States (Office of Education, United States Department of the Interior, 1935). online

- Maxwell, William H. A quarter century of public school development (1912) online

- Moore, Ernest C. How New York city administers its schools; a constructive study (1913) online

- Palmer, A. Emerson. The New York public school: being a history of free education in the city of New York (1905) online

External links

[edit]- Andy Mccarthy, "Class Act: Researching New York City Schools with Local History Collections", summary story of NYC schools since colonial era; guide to further research; well illustrated