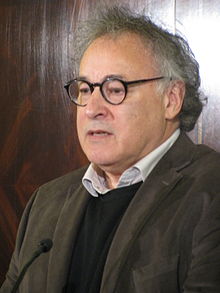

Howard Norman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Howard Alan Norman[1] 1949 Toledo, Ohio, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer, educator |

| Education | |

| Subject |

|

| Notable works | The Bird Artist |

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse | Jane Shore |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Howard Alan Norman (born 1949), is an American writer and educator. Most of his short stories and novels are set in Canada's Maritime Provinces. He has written several translations of Algonquin, Cree, and Inuit folklore. His books have been translated into 12 languages.[2]

Early years

[edit]Norman was born in Toledo, Ohio. His parents were Russian-Polish-Jewish; they met in a Jewish orphanage.[citation needed] The family moved several times, and Norman attended four different elementary schools, including in Grand Rapids, Michigan. His mother watched other children while his father was away most of the time. He is one of three brothers.[3]

After dropping out of high school, Norman moved to Toronto. Working in Manitoba on a fire crew with Cree Indians, Norman became fascinated with their folkstories and culture. He spent the next 16 years living and writing in Canada, including the Hudson Bay area and the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. During this time, he received his high school equivalency diploma, and studied later at Western Michigan University Honors College[4] where he received Bachelor of Arts degrees in zoology and English[citation needed] in 1972.[5] In 1974, he earned a Master of Arts degree from the Folklore Institute of Indiana University linguistics and folklore;[4] his Masters thesis was entitled, Fatal Incidents of Unrequited Love in Folktales Around the World.[4]

For the next three years, he participated in the Michigan Society of Fellows;[4][6] The Cree personal name was published in 1977.[7] Shortly after, his father died in 1996, who Norman had not seen in 20 years.

Career

[edit]"I said this in a nonfiction book, and I’ll repeat it at the risk of quoting myself: when I wake up in Halifax or Nova Scotia, there is a shorter distance between my unconscious life and my conscious life than anywhere else, I feel more complete and more whole." (H.A. Norman, 2004)

- Writer

Norman has been a prolific writer in a variety of styles. How Glooskap Outwits the Ice Giants, The owl-scatterer, and Between heaven and earth are written for juvenile audiences. His books on Canadian folklore include The wishing bone cycle (Cree), Who met the ice lynx (Cree), Who-Paddled-Backward-With-Trout (Cree), The girl who dreamed only geese (Inuit) Trickster and the fainting birds (Algonquin), and Northern tales (Eskimo). Northern Tales, translated into Italian and Japanese, was Norman's first book translated into a foreign language.[9] In Fond Remembrance of Me is not only an English translation of Noah and the Ark stories as told by a Manitoba Inuit elder, it is also a memoir of the friendship that Norman kindles with Helen Tanizaki, a writer who is translating these same stories into Japanese before her death.

Norman describes The Bird Artist, a novel, as his most conservative book structurally, though not psychologically.[8] Time magazine named The Bird Artist one of its Best Five Books for 1994. It also was awarded the New England Booksellers Association Prize in Fiction, and Norman received a Lannan Literary Award for this book.[10] The Bird Artist and The Northern Lights were finalists for the National Book Award. The Northern Lights was completed with assistance from the Whiting Award.[3] He received the Harold Morton Landon Translation Award from the Academy of American Poets for The Wishing Bone Cycle.[11] In On the trail of a ghost, an article published by National Geographic, Norman writes about Japan's haiku master, Matsuo Bashō's 1200-mile walk in 1689, and the journey's epic log, entitled Oku no Hosomichi.[12] His book, My Famous Evening: Nova Scotia Sojourns, Diaries & Preoccupations was published under National Geographic's "Directions" travel series. It includes a chapter on the Nova Scotia poet Elizabeth Bishop.

There are also several early books published in small numbers. These include: The Woe Shirt, Arrives Without Dogs, and Bay of Fundy Journal, amongst others.[9]

- Teacher

In 1999, Norman taught at Middlebury College in Vermont.[13] Norman became Goucher College's Writer in Residence in 2003.[11] In 2006, he was appointed a Marsh professor at University of Vermont.[14] Norman now teaches creative writing in the Masters of Fine Arts program at the University of Maryland, College Park.

- Professional affiliations

Norman has contributed to book review periodicals (The New York Times Book Review; Los Angeles Times Book Review; National Geographic Traveler), participated on literary journals' editorial staff (Conjunctions: Ploughshares), and been a member of the board of directors for PEN New York and PEN/Faulkner group, Washington, D.C.[4]

Personal life

[edit]Norman met poet Jane Shore in 1981, and they married in 1984.[citation needed] They have a daughter, Emma.

Norman and Shore lived in Cambridge, New Jersey, Oahu, and Vermont, before settling into homes in Chevy Chase, Maryland near Washington, D.C. during the school year, and East Calais, Vermont[15] in the summertime.[3][16][17] Their friend, the author David Mamet, Shore's Goddard College classmate, lives nearby.[18]

During the summer of 2003, poet Reetika Vazirani was housesitting the Norman's Chevy Chase home. There, on July 16, she killed her young son before committing suicide.[19][20]

Howard Norman's papers are housed in the Sowell Collection in the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library of Texas Tech University.

Awards

[edit]- Guggenheim Fellowship[5]

- National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships (x3)[21]

- National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship[21]

- 2001, Distinguished Alumni Award, Western Michigan University

- 1996, Lannan Literary Award for Fiction[22]

- 1986, Whiting Award[23]

- 1978, Harold Morton Landon Translation Award[24]

Partial list of works

[edit]- (1976). The Wishing Bone Cycle: Narrative poems from the Swampy Cree Indians. ISBN 0-88373-045-6

- (1978). Who Met the Ice Lynx: Naming stories of the Swampy Cree people. ISBN 0-916914-02-X

- (1986). The Owl-Scatterer. ISBN 0-87113-058-0

- (1987). Who-Paddled-Backward-With-Trout. ISBN 0-316-61182-4

- (1987). The Northern Lights: A novel. ISBN 0-671-53231-6

- (1989). How Glooskap Outwits the Ice Giants; and other tales of the Maritime Indians. ISBN 0-316-61181-6

- (1989). Kiss in the Hotel Joseph Conrad and other stories. ISBN 0-671-64419-X

- (1990). Northern Tales: Traditional stories of Eskimo and Indian peoples. ISBN 0-394-54060-3

- (1994). The Bird Artist. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-11330-0

- (1997). The Girl Who Dreamed Only Geese, and other tales of the Far North. ISBN 0-15-230979-9

- (1998). The Museum Guard. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-21649-5

- (1999). Trickster and the Fainting Birds. ISBN 0-15-200888-8

- (2002). The Haunting of L. Farrar, Straus ISBN 0-374-16825-3

- (2004). Between Heaven and Earth: Bird tales from around the world. ISBN 0-15-201982-0

- (2004). My Famous Evening: Nova Scotia sojourns, diaries & preoccupations. ISBN 0-7922-6630-7

- (2005). In fond Remembrance of Me. ISBN 0-86547-680-2

- (2007). Devotion. ISBN 978-0-618-73541-9

- (2008). "On the Trail of a Ghost". National Geographic. 213 (2), 137–149. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. OCLC 227005140

- (2010) What Is Left the Daughter ISBN 978-0-618-73543-3

- (2013). I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place. ISBN 978-0-547-38542-6

- (2014). Next Life Might Be Kinder. ISBN 978-0-547-71212-3

- (2017). My Darling Detective. ISBN 978-0544236103

- (2019). The Ghost Clause. ISBN 978-0544987296

- (2024). Come to the Window: A Novel. Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 9781324076339

In 1989, in the same issue of International Journal of American Linguistics, the American Indian language scholar Robert Brightman published an article titled "Tricksters and Ethnopoetics" in which he argued that the trickster cycle which appears in "The Wishing Bone Cycle" was originally recorded by the American linguist Leonard Bloomfield from the Cree story teller Maggie Achenam in 1925 and that Norman took Bloomfield's prose version and rewrote it in more poetic language.

References

[edit]- ^ "Norman, Howard A." at Library of Congress Linked Data Service.

- ^ "The Bird Artist". Living Writers Wired. colgate.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-09-28. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ a b c Huppért, Margaritte; Don Lee. "About Howard Norman: A Profile". Ploughshares. Emerson College. Archived from the original on 2008-02-20.

- ^ a b c d e "Press Release". houghtonmifflinbooks.com. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ a b "2001 Distinguished Alumni Award Recipient". wmich.edu. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ "The Michigan Society of Fellows". rackham.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-01-17. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ Norman, Howard A. The Cree personal name. worldcat.org. OCLC 184855188.

- ^ a b "An Interview with Howard Norman". wmich.edu. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-08-11. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ a b Lopez, Ken (1998). "Collecting Howard Norman". lopezbooks.com. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ^ "Howard Norman". answers.com. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ a b "Howard Norman". Ploughshares. Emerson College. September 8, 2005. Archived from the original on 2009-11-15.

- ^ Norman, Howard (February 2008). "Basho". National Geographic. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008.

- ^ "1999 Faculty". middlebury.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-10-19. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ "Howard Norman". uvm.edu. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ Doten, Patti Doten (August 30, 1994). "The Bird man of east Calais, Vt. Novelist Howard Norman hatches ideas in his mountain home". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ "Jane Shore". Poetry Quarterly. 2 (2). washingtonart.com. Spring 2001.

- ^ Norman, Howard (Fall 2003). "Guest Editor's Note". Conjunctions. 41. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ Goldstein, M.M. (October 1, 1998). "The Ups, Downs and Up Again of the Book Deal". newenglandfilm.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ "Senseless tragedy strikes the American poetry scene". chicagopoetry.com. December 5, 2004. Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ Fiore, Kristina (September 9, 2003). "A loss for words: Reetika Vazirani, poet and professor, commits suicide at 40". The Signal. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ a b "Northern Tales". nebraskapress.unl.edu. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ "Literary Awards by Last Name". lannan.org. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ "Recipients of the Whiting Writers Awards 2008-1985". whitingfoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ "Harold Morton Landon Translation Award". poets.org. Archived from the original on 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2009-01-25.