This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

|

|---|

|

|

| Constitution |

|

|

Human rights in post-invasion Iraq have been a subject of concern and controversy since the 2003 U.S. invasion. Issues have been raised regarding the conduct of insurgents, U.S.-led coalition forces, and the Iraqi government. The United States is investigating several allegations of violations of international and domestic standards of conduct in isolated incidents involving its forces and contractors. Similarly, the United Kingdom is conducting investigations into alleged human rights abuses by its forces. War crime tribunals and criminal prosecutions for numerous crimes committed by insurgents are likely still years away. In late February 2009, the U.S. State Department released a report on the human rights situation in Iraq, reflecting on developments during the previous year (2008).[1]

Human rights abuses by insurgents

[edit]

Human rights abuses carried out or alleged to have been carried out by Iraq-based insurgents and/or terrorists include:

August 2003

[edit]The bombing of the U.N. headquarters in Baghdad in August 2003 resulted in the death of the top U.N. representative in Iraq, 55-year-old Sérgio Vieira de Mello, a Brazilian diplomat who also served as the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.[2] The attack claimed the lives of 22 U.N. staff members and injured more than 100 others. Among the dead was Nadia Younes, a former Executive Director at the World Health Organization (WHO) in charge of External Relations and Governing Bodies. The terrorist attack was strongly condemned by U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan and denounced by the U.N. Security Council.[3]

June 2004

[edit]South Korean translator Kim Sun-il was beheaded by followers of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.[4]

July 2004

[edit]Tawhid and Jihad killed Bulgarian truck drivers Ivaylo Kepov and Georgi Lazov. Al-Jazeera aired a videotape of the incident but stated that the segment showing the actual killings was too graphic to broadcast.[5]

December 2004

[edit]Salvatore Santoro, a 52-year-old Italian photographer, was beheaded in a video. The Islamic Movement of Iraqi Mujahedeen claimed responsibility for the act.[4]

February 2005

[edit]Al-Iraqiya TV (Iraq) aired transcripts of confessions by Syrian intelligence officer Anas Ahmad Al-Issa and Iraqi terrorist Shihab Al-Sab'awi. The confessions detailed their involvement in booby-trap operations, explosions, kidnappings, assassinations, and training for beheadings in Syria.[6]

July 2005

[edit]Egyptian and Algerian envoys.

- Two Algerian diplomats, Ali Belaroussi and Azzedine Belkadi, were reported to have been killed by al-Qaeda in Iraq. The group issued a statement online claiming responsibility, stating: “The court of al-Qaeda in Iraq has decided to carry out God’s verdict against the two diplomats from the apostate Algerian government ... and ordered to kill them.” The statement was signed by Abu Maysara al-Iraqi, the al-Qaeda spokesman.[7]

- An Egyptian diplomat, Al-Sherif, was reported to have been killed by al-Qaeda in Iraq. The group posted a statement on a web forum claiming responsibility for the killing. Top Sunni cleric Mohamed Sayed Tantawi condemned the act, describing it as "a crime against religion, morality, and humanity, as well as a crime that goes against honor and chivalry."[8]

February 2006

[edit]The Al Askari Mosque bombing took place on February 22, 2006, at approximately 6:55 am local time (0355 UTC) at the Al Askari Mosque, one of the holiest sites in Shi'a Islam, in the Iraqi city of Samarra, about 100 km (62 mi) northwest of Baghdad. Although no injuries were reported from the blast itself, the bombing led to violence in the following days. On February 23, over 100 dead bodies with bullet holes were found, and at least 165[9] people are believed to have been killed.

June 2006

[edit]A video showing the killing of four Russian diplomats kidnapped in Iraq was posted on the Internet. The group called the Mujahideen Shura Council released the hostage video.[10]

July 2006

[edit]Anba' Al-Iraq News Agency and the Writers Without Borders Organization condemned the imprisonment of its staff member, Husain E. Khadir, who was responsible for covering documentaries about the threats posed by the Kurdistan Federal Region to its neighboring countries. A delegation from Human Rights Watch (HRW) released reports on torture in Iraq, as well as the repression of human rights and freedom of expression. HRW interviewed several detained writers and journalists to document these violations. Mr. Khadir was first detained in Kirkuk and later moved to Erbil, where HRW visited him in one of the detention centers.

The previous year in Baghdad, Khadir faced even worse conditions when he escaped from a Shi'a militia that had seized his house and thrown his family into the streets, an act seen as a serious threat to his life. Such actions are commonly directed at human rights activists, journalists, and writers who criticize the Iraqi government and the Shi'a coalition party. During the constitution-writing process, several press and media agencies strongly criticized the Iraqi Shi'a Coalition. Khadir led a campaign to amend the constitution, advocating for a document that would serve as a peace-building tool, bringing all parties together for national consensus and social cohesion, rather than merely serving as a state-building instrument, as the ruling party frequently stated.

UNAMI commented that most of these civil society activities were supported by UN agencies, international donors, or the U.S. and British governments. The IRIN/UN news agency revealed that journalists and writers are among the most vulnerable victims of killing, threats, kidnapping, torture, and detention, practices commonly carried out by uncontrolled Iraqi forces, paramilitary organizations, and Shi'a or Sunni militias. This situation, similar to Khadir's case, is spreading across southern, central, and northern Iraq.[11]

The number of journalists and writers killed in Iraq has exceeded 220 this year, according to the Iraqi Organization for Supporting Journalists, as reported to IRIN.[12]

U.S. National Guard Sergeant Frank "Greg" Ford claimed to have witnessed human rights violations in Samarra, Iraq. However, a subsequent Army investigation found Ford's allegations to be unfounded. Additionally, Ford was discovered to have worn unauthorized "U.S. Navy SEAL" insignia on his Army uniform, despite having never been a Navy SEAL, a claim he had made for many years while serving in the Army National Guard.

- The Kuwaiti News Agency reported that a high-ranking Iraqi security source in the Interior Ministry confirmed the final death toll of the 13 August bombings in the Al-Zafaraniyah district in southern Baghdad was 57 killed and 145 injured, most of them women and children.[13] Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki blamed Sunni extremists for seeking to escalate the conflict.[14]

Human rights abuses by coalition forces

[edit]

Prison and interrogation abuses by coalition forces

[edit]April 2003

[edit]On April 29, 2003, an Iraqi man, Ather Karen al-Mowafakia, was shot and killed by a British soldier at a roadside checkpoint. Witnesses alleged that he was shot in the abdomen after the door of his car struck a soldier's leg as he was getting out of the vehicle. They further claimed he was then dragged from the car and beaten by the soldier's comrades, later succumbing to his injuries in the hospital. Despite seven attempts by The Guardian to address the incident, the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) has refused to explain why the individuals were detained or provide details on where, how, or why they died.[15]

May 2003

[edit]In May 2003, Saeed Shabram and his cousin, Menem Akaili, were detained by British troops and thrown into a river near Basra. Akaili survived, but Shabram drowned. According to Akaili, the two were approached by a British patrol, led at gunpoint to a jetty, and forced into the water. The act, referred to as "wetting," was reportedly used to humiliate local youths suspected of looting.

"Wetting was supposed to humiliate those suspected of being petty criminals," said Sapna Malik, the family's lawyer from Leigh Day and Co. "Although the Ministry of Defence (MOD) denies the existence of a policy of wetting to deal with suspected looters at the time, evidence we have seen suggests otherwise. The tactics employed by the MOD appeared to include throwing or placing suspected looters into either of Basra's two main waterways."

Iraqi bystanders rescued Akaili, but Shabram disappeared. His body was later recovered by a diver hired by his father, Radhi Shabram, after a four-hour search while his mother waited on the riverbank. "When Saeed's corpse was finally pulled from the river, Radhi described it as bloated and covered with marks and bruises," Malik added.

Although the MOD paid compensation to Shabram's family, none of the soldiers involved were charged in connection with his death.[16]

Ahmed Jabbar Kareem Ali, a 15-year-old boy, was on his way to work with his brother on May 8, 2003, when he was assaulted by a group of British soldiers. The soldiers beat him and then forced him into a canal at gunpoint to "teach him a lesson" for suspected looting. Weakened from the beating, Ali struggled in the water and drowned. His lifeless body was later pulled from the canal.

In a separate case involving the death of another Iragi teenager, four British soldiers were acquitted of manslaughter.[17][18]

August 2003

[edit]Hanan Saleh Matrud, an eight-year-old Iraqi girl, was killed on August 21, 2003, by a soldier from the King's Regiment when a Warrior armoured vehicle stopped near an alley leading to her home. Three or four soldiers exited the vehicle, attracting a group of children, including Hanan. Accounts of what happened next differ.

The soldiers claimed they came under attack from a mob throwing stones, prompting a "warning shot" to be fired. However, local witnesses alleged that the crowd consisted only of children, who had been "coaxed into the open by the soldiers' offers of chocolate." Hanan was shot in the lower torso and rushed by the soldiers to a Czech-run hospital, where she died the following day after an unsuccessful operation.

According to the Ministry of Defence (MOD), "in the absence of impartial witness evidence or forensic evidence to suggest a soldier had acted outside the rules of engagement, no crime was established." In May 2004, following an intervention by Amnesty International, Hanan's family submitted a formal claim for proper compensation, which was under assessment by the MOD as of that time.[19]

September 2003

[edit]On September 14, Baha Mousa, a 26-year-old hotel receptionist, was arrested along with six other men and taken to a British military base. While in detention, Mousa and the other captives were hooded, severely beaten, and assaulted by several soldiers at the base. Two days later, Mousa was found dead.[citation needed]

A post-mortem examination revealed that Mousa had sustained multiple injuries—at least 93—including fractured ribs and a broken nose, which were identified as contributing factors to his death.[20]

Seven members of the Queen's Lancashire Regiment were tried on charges related to the ill-treatment of detainees, including war crimes under the International Criminal Court Act 2001. On September 19, 2006, Corporal Donald Payne pleaded guilty to a charge of inhumane treatment of persons, making him the first member of the British Armed Forces to plead guilty to a war crime.[21] He was subsequently sentenced to one year in prison and expelled from the army.

The BBC reported that the six other soldiers were cleared of any wrongdoing.[22] The Independent stated that the charges against them had been dropped, with the presiding judge, Justice Ronald McKinnon, noting: "None of those soldiers has been charged with any offence, simply because there is no evidence against them as a result of a more or less obvious closing of ranks."[23]

January 2004

[edit]On January 1, Ghanem Kadhem Kati, an unarmed young man, was shot twice in the back by a British soldier at the door of his home. Troops had arrived at the scene after hearing gunfire, which neighbors reported was coming from a wedding party.

Six weeks later, investigators from the Royal Military Police exhumed the teenager's body. However, no compensation has been offered, and the inquiry's conclusion has yet to be announced.[24]

Video footage from the gun camera of a U.S. Apache helicopter in Iraq, showing the killing of suspected Iraqi insurgents, was aired on ABC TV.[26] The case sparked controversy due to the ambiguity of the video. In the footage, a cylindrical object is tossed on the ground in a field. The U.S. military identified the object as an RPG or mortar tube and subsequently fired upon the individuals.

However, IndyMedia UK suggested that the objects might have been harmless tools or implements. The publication also alleged that the helicopter fired upon a man who appeared to be wounded, which they argued would contradict international laws.[27][28]

Retired U.S. Army General Robert Gard stated on German television that, in his opinion, the killings were "inexcusable murders."[29]

April 2004

[edit]On April 14, Lieutenant Ilario Pantano of the United States Marine Corps killed two unarmed captives. Pantano claimed that the captives had advanced on him in a threatening manner. The officer presiding over his Article 32 hearing recommended a court-martial for "body desecration." However, all charges against Pantano were dropped due to a lack of credible evidence or testimony. He later separated from the Marine Corps with an honorable discharge.

In February 2006, a video showing a group of British soldiers apparently beating several Iraqi teenagers was posted on the internet and soon broadcast on major television networks worldwide. The video, filmed in April 2004, was taken from an upper storey of a building in the southern Iraqi town of Al-Amarah. It shows a crowd of Iraqis outside a coalition compound.

After an altercation in which members of the crowd reportedly threw rocks and an improvised grenade at the soldiers, the soldiers rushed the crowd. They brought some Iraqi teenagers into the compound and proceeded to beat them. The video also includes a voiceover, apparently by the cameraman, taunting the beaten teenagers.

The person recording could be heard saying:

- Oh, yes! Oh Yes! Now you gonna get it. You little kids. You little motherfucking bitch!, you little motherfucking bitch.[30]

The event was broadcast in mainstream media, leading the British government and military to condemn it. The incident raised particular concerns for British soldiers, who had previously enjoyed a more favorable position than American soldiers in the region. Following the incident, there were media reports expressing concerns about the safety of soldiers in the country.

While the tape received some criticism from Iraq, it was relatively muted, and media outlets found individuals willing to speak out. The Royal Military Police conducted an investigation, but the prosecuting authorities determined that there was insufficient evidence to justify court-martial proceedings.[31]

May 2004

[edit]In May 2004, a British soldier identified as M004 mistreated captured, unarmed prisoners of war during a "tactical questioning" at Camp Abu Naji.[citation needed]

See: Mukaradeeb wedding party massacre

On May 19, 2004, the village of Mukaradeeb was attacked by American helicopters, resulting in the deaths of 42 men, women, and children. The casualties included 11 women and 14 children, as confirmed by Hamdi Noor al-Alusi, the manager of the nearest hospital. Western journalists also viewed the bodies of the children before they were buried.[32]

November 2005

[edit]See: Haditha killings

On November 19, 24 Iraqis were killed, at least 15 of whom, and allegedly all, were non-combatant civilians. All are believed to have been killed by a group of U.S. Marines. The ongoing investigation into the incident claimed to have found evidence that "supports accusations that U.S. Marines deliberately shot civilians, including unarmed women and children," according to an anonymous Pentagon official.[33]

March 2006

[edit]See: Mahmudiyah killings

On March 12, an Iraqi girl was raped and murdered along with her family in the Mahmudiyah killings. The incident led to the prosecution of the offenders and sparked a number of reprisal attacks against U.S. troops by insurgent forces.

See: Ishaqi incident

On March 15, 11 Iraqi civilians were allegedly bound and executed by U.S. troops in what is known as the "Ishaqi incident." A U.S. investigation concluded that military personnel had acted appropriately and followed the proper rules of engagement, responding to hostile fire and gradually escalating force until the threat was eliminated. The Iraqi government rejected the American conclusions. In September 2011, the Iraqi government reopened their investigation after WikiLeaks published a leaked diplomatic cable highlighting concerns raised by U.N. inspector Philip Alston, the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary, or Arbitrary Executions.[34]

April 2006

[edit]See: Hamdania incident

On April 26, U.S. Marines shot and killed an unarmed Iraqi man. An investigation by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service led to charges of murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy related to the cover-up of the incident. The defendants include seven Marines and a Navy Corpsman. As of February 2007, five of the defendants had pleaded guilty to lesser charges of kidnapping and conspiracy and agreed to testify against the remaining defendants, who face murder charges. Additional Marines from the same battalion faced lesser charges of assault related to the use of physical force during interrogations of suspected insurgents.

May 2006

[edit]On May 9, U.S. troops from the 101st Airborne Division executed three male Iraqi detainees at the Muthana Chemical Complex. An investigation and lengthy court proceedings followed. Spc. William Hunsaker and Pfc. Corey Clagett both pleaded guilty to murder and were each sentenced to 18 years for premeditated murder. Spc. Juston Graber pleaded guilty to aggravated assault for shooting one of the wounded detainees and was sentenced to nine months. A fourth soldier, Staff Sgt. Ray Girouard of Sweetwater, Tennessee, was convicted of obstruction of justice, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and violation of a general order.[35][36]

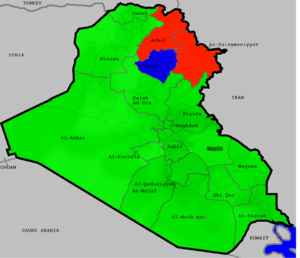

Human rights in northern Iraq

[edit]In Iraqi Kurdistan, according to a 1995 Amnesty International report, the "prime responsibility for human rights abuses lies with the two parties holding the reins of power in Iraqi Kurdistan — the KDP and PUK," due to their political and military dominance. Amnesty reported that Francis Yusuf Shabo, an Assyrian Christian politician responsible for addressing complaints by Assyrian Christians about disputed villages, was shot dead on May 31, 1993, in Duhok, and no one had been brought to justice. Similarly, Lazar Mikho Hanna (known as Abu Nasir), another Assyrian Christian politician, was shot dead on June 14, 1993, in Duhok.

Amnesty criticized the impunity granted to Kurdish political parties' armed and special forces, noting that assailants were not held accountable. The report highlighted the "active undermining of the judiciary and the lack of respect for its independence by the political parties." It also documented incidents where Kurdish forces "arrested people arbitrarily," tortured detainees, killed civilians, and failed to bring perpetrators to justice.[37]

The UNHCR reported incidents of violence against political opponents and minorities in areas under Kurdish control. Minority leaders have alleged that Kurdish political parties and forces have subjected them to violence, forced assimilation, discrimination, political marginalization, and arbitrary arrests and detention. The UNHCR noted that Kurdish parties and forces have been "considered responsible for arbitrary arrests, incommunicado detention, and torture of political opponents and members of ethnic/religious minorities."

The report also highlighted complaints from Christians about Kurdish attempts to assimilate them, as well as allegations of "the use of force, discrimination, and electoral fraud by Kurdish parties and militias." One notable incident occurred in October 2006, when KRG forces reportedly raided the building of a Christian media organization and detained its staff.

The UNHCR reported claims from Christian parties alleging "harassment and forced assimilation by Kurdish militias in Kirkuk and surrounding areas, with the aim of incorporating these areas into the Region of Kurdistan." Christians have accused Kurdish parties and their military forces of engaging in "acts of violence and discrimination, arbitrary arrests and detention on sectarian grounds, political marginalization (including through electoral manipulations), monopolization of government offices, and altering demographics to incorporate Kirkuk and other mixed areas into the Region of Kurdistan."

The Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) described this strategy as a form of "soft ethnic cleansing."[38] According to the UNHCR, Christians have repeatedly complained about ongoing Kurdification efforts. The U.S. State Department also reported that "Kurdish authorities abused and discriminated against minorities in the North, including Turkmen, Arabs, Christians, and Shabak."

The UNHCR further noted that Kurdish parties "denied services to certain villages, arrested minorities without due process, detained them in undisclosed locations, and pressured minority schools to teach in the Kurdish language."[39] [note 1] Additionally, Christians and Shabak people alleged that in the 2005 elections, "non-resident Kurds entered polling centers, and over 200 votes were cast illegally before the Multi-National Force intervened to stop the voting irregularities."[41]

In 2005, a peaceful demonstration by Shabak people "turned violent after KDP gunmen shot at the crowd."[42][43] The UNHCR reported that Christians were at "risk of arbitrary arrest and incommunicado detention" by Kurdish forces. The Washington Post highlighted extrajudicial detentions as early as 2005, describing a "concerted and widespread initiative" by Kurdish parties to assert authority in Kirkuk in an increasingly provocative manner. The report noted that arbitrary arrests and abductions by Kurdish militias had "greatly exacerbated tensions along purely ethnic lines."

The UN Assistance Mission for Iraq's Human Rights Office (UNAMI HRO) stated in 2007 that religious minorities "face increasing threats, intimidation, and detentions, often in KRG facilities run by Kurdish intelligence and security forces."[44] The Washington Post estimated that there were 600 or more extrajudicial transfers, with detainees reporting "arbitrary arrests, incommunicado detentions, the use of torture, and unlawful confiscation of property."[45]

Abuses by Kurdish forces ranged from "threats and intimidation to detention in undisclosed locations without due process."[46] The Kurdish parties’ plans to incorporate "disputed areas" like Kirkuk into Kurdistan were met with resistance from Christian, Arab, and Turkmen groups.

The UNHCR noted that Christians and Arabs in Mosul, Kirkuk, and surrounding areas, which are "under de facto control of the KRG," have become victims of threats, harassment, and arbitrary detention. The UNHCR also reported that Christian and Arab internally displaced people (IDPs) face discrimination and that those expressing opposition to the Kurdish parties, such as by participating in demonstrations, risk "arbitrary arrest and detention."

The KDP and PUK have been "repeatedly accused of nepotism, corruption, and lack of internal democracy," according to the UNHCR. Journalists have claimed that press freedom is restricted and that criticism of the ruling parties can result in physical harassment, the seizure of cameras and notebooks, and arrest.[47] For example, Kamal Sayid Qadir was sentenced to 30 years in prison after writing critically about Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani. The sentence was later reduced due to international pressure.[38][48]

The UNHCR also reported arbitrary detentions of suspected political opponents by Kurdish authorities. Minorities have complained about "forcible assimilation into Kurdish society," increased discrimination against the non-Kurdish population, and efforts to dominate and "kurdify" traditionally mixed areas like Kirkuk. A 2006 poll conducted in Erbil, Sulaymaniyah, and Dahuk revealed that 79% of Kurds opposed allowing Arabs to enter Iraqi Kurdistan, and 63% opposed their settlement in the region.[38]

Assyrian groups have stated that Kurdish authorities alter historical and geographical facts in school textbooks. For example, Assyrian Christian places are reportedly given new Kurdish names, and historical or Biblical figures are claimed to be Kurdish.[49][50]

The American Mesopotamian Organization (AMO) demanded an official apology from Kurdistan President Massoud Barzani for the murder of Assyrians by Kurds in the past, alleging that thousands of Assyrian Christians were killed in the region over the last century. The AMO also criticized a message from Barzani on the occasion of Assyrian Martyrs Remembrance Day, which coincided with the 80th anniversary of the Semile massacre. The massacre, conducted by Kurdish general Bakr Sidqi, was referenced in Barzani's message, which controversially portrayed the Assyrians killed in the Simmele massacre as martyrs in the "Kurdistan liberation movement."[51][52]

Assyrians in the Iraqi Kurdistan region face significant discrimination in various fields of work. Christian Assyrians are often limited to jobs as salespeople in liquor shops or as beauticians in salons, making them targets for Muslim extremists. In 2011, many Assyrian shops were burned. Additionally, Assyrians are reportedly excluded from professions such as police officers, soldiers, journalists for major media outlets, judges, and senior positions within educational institutions.

Local Assyrian history in the KRG-controlled area is often rebranded as Kurdish history. City names have been changed to Kurdish, and Assyrian heritage sites are reportedly neglected or destroyed. Furthermore, Assyrian history is not acknowledged in school textbooks, museums, or during memorial days.[53]

There are also claims that Kurdish criminal organizations force Assyrian girls, particularly vulnerable refugees from southern Iraq, into prostitution. Those who refuse reportedly face death threats. These organizations are said to have ties to political leaders, enabling them to quickly issue passports and send these girls to European Union countries to work in the sex trade.[53]

Assyrians allege that Kurds are actively working to "Kurdify" the local Christian population in northern Iraq. Reports indicate that Christians are sometimes forced to identify as Kurds to access essential services like education or healthcare. Similarly, Yazidis and Shabaks are not recognized as distinct ethnicities, and Assyrians from northern Iraq are increasingly pressured to identify as "Kurdistani" or "Kurdish Christians."

The KRG has also been accused of discriminatory practices against non-Kurdish minorities. Many Assyrians and Yazidis in the Nineveh Plains claim that the KRG has confiscated their property without compensation and has begun constructing settlements on their land. There have also been allegations of killings of Assyrians by agents of Kurdish political parties.

Reports suggest that the KRG uses tactics such as intimidation, threats, restricted access to services, arbitrary arrests, and extrajudicial detentions to pressure political opponents and ordinary members of minority communities into supporting the KRG’s efforts to expand into disputed territories.[note 2]

In 2014, Assyrians accused the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) of systematically disarming and abandoning Assyrian and other minority communities in anticipation of an ISIS assault. The KRG reportedly distributed notices to Assyrians in northern Iraq, demanding their complete disarmament and assuring them that the Kurdish Peshmerga would protect them against ISIS. However, when ISIS launched its attacks, the Peshmerga abruptly retreated.

A similar situation occurred in the Sinjar region and Shingal, where Kurdish Peshmerga forces retreated as ISIS advanced in 2014.[63][64] Peshmerga General Holgard Hekmat, a spokesman for the Peshmerga Ministry, admitted in an interview with SpiegelOnline: “Our soldiers just ran away. It’s a shame and apparently a reason why they invent such allegations.”[65][66]

As a result of these events, approximately 150,000 Assyrian Christians were violently displaced from their ancestral homes in the Nineveh Plains.[58] A KRG official was quoted in a Reuters article in 2014, stating, “ISIL gave us in two weeks what Maliki couldn’t give us in eight years.”[58]

Some Assyrians activists claim they have suffered not only from Arabization but also from Kurdification in Iraqi Kurdistan. These activists allege that the number of Christians living in the region has declined due to the destruction of villages and the implementation of Kurdification policies.[67]

Historically, Christians, including Assyrian Christians, made up a much larger proportion of the population in northern Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan than they do today. Their numbers have significantly decreased due to massacres, displacement, and other factors.

Additionally, the region is home to crypto-Christians—individuals who outwardly identify as Kurdish Muslims but retain memories of their Armenian or Nestorian Christian heritage. Relations between the remaining Christian population and the Kurds have often been strained.[68]

According to Assyrian expert Michael Youash, some Christians became refugees because Kurds seized their land, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) failed to assist them in reclaiming it.[69] In 2007, Youash also reported "numerous instances of Kurdish authorities discriminating against minorities in the North," noting that authorities denied services to certain villages, arrested minorities without due process, and pressured minority schools to teach in Kurdish.[69]

Additionally, reports indicate that Christians who lack political representation struggle to expand their schools and often face exclusion from anything beyond basic funding.[67] Assyrian groups criticized the Kurdish authorities' investigations into a series of bombings targeting Christians in 1998 and 1999.[70]

Assyrians have also been victims of attacks by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and have often been caught in intra-Kurdish conflicts. For instance, in 1997, six Assyrians were killed during a PKK attack in Dohuk.[70] A 1999 U.S. government country report cited allegations by the Assyrian International News Agency about the murder and rape of Helena Aloun Sawa, an Assyrian housekeeper for a KDP politician. Assyrians alleged that this case fit a "well-established pattern" of Kurdish authorities' complicity in attacks against Assyrian Christians in northern Iraq.[70]

In more recent times, some scholars have noted that in northern Iraq, particularly in the area of "ancient Assyria," Kurdish expansion has come at the expense of the Assyrian population. Due to both Arab and Kurdish intimidation policies, particularly by the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP), the Aramaic-speaking Christian population has been significantly reduced. It has been claimed that Kurds have "raised impediments to the acquisition of international aid for development, attempted to prevent the establishment of Aramaic language schools, and blocked the creation of Christian Assyrian schools." These issues have also been criticized by the U.S. State Department.

Additionally, attacks on Christians have been perpetrated by both Arab and Kurdish Islamist groups, such as ISIS and the Kurdish Ansar ul-Islam.[71][72] [note 3] Kurdish forces have also been accused of harassing Arab residents.[74][75]

Assyrian Christian refugees have been blocked from returning to their villages across the Nineveh Plain by the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG), according to a report from The Investigative Project on Terrorism. Jeff Gardiner, director of Restore Nineveh Now, stated, "The Kurdish authorities did not protect the people of the Nineveh Plain. In a way, this was enabled by the Kurdish government. They really set them [Assyrians] up for this catastrophic outcome." Gardiner dismissed claims of a security risk, calling the KRG's actions a "land grab."

Robert Nicholson of The Philos Project remarked, "For months we've been receiving numerous reports from Assyrian Christians and Yazidis that Kurdish forces are using the fog of war to seize land that rightfully belongs to victims of genocide. Each week those reports are increasing. The Nineveh Plain has never been a Kurdish territory. It belongs to the Christians (Assyrians) and Yazidis who have been living there for thousands of years." Members of the Nineveh Protection Units, an Assyrian militia, have faced obstruction by the KRG, with their movements impeded by Kurdish forces.[76]

In a letter to Kurdistani President Masoud Barzani, John McCain expressed concern about "reports of land confiscation and statements you have made regarding Kurdish territorial claims to the Nineveh Plains region." According to Gardner, "This is nothing new. Assyrian Christians complained about the illegal settlement of Kurdistani families on Assyrian land in the early 1990s. The ultimate strategy aims to unify Iraq's Kurds with those in Syria and Turkey in a broader Kurdish state."[77][78][79]

In December 2011, hundreds of Kurds in Zakho burned and destroyed Christian Assyrian businesses and hotels after Friday prayers. Human rights groups suggested that the riots were planned by Kurdish authorities, noting that security representatives had made inquiries about liquor stores three days before the riots and that security forces did not intervene to stop the violence. Assyrians also face discrimination in the labor market and are burdened with administrative tasks, such as the annual requirement for Internally Displaced Persons to obtain a residence permit. Assyrian students are treated and graded differently from Kurdish students. Additionally, Assyrians "suffer abuses and discrimination as a result of the KRG's aspirations to extend its control and its plans to reshape the demographics of Mosul and the Nineveh Plains." An official police force composed of Assyrians "has not been established due to massive resistance from Kurdish groups."[80]

Government complicity in "religiously motivated discrimination has been reported in the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG)." According to the State Department, Christians "living in areas north of Mosul asserted that the KRG confiscated their property without compensation," and Assyrian Christians also alleged that the Kurdish Democratic Party-dominated judiciary routinely discriminates against non-Muslims. Chaldo-Assyrian Christians have stated that KRG officials "deny Christians key social benefits, including employment and housing," and that "foreign reconstruction assistance for Assyrian communities is being controlled by the KRG." KRG officials have used "public works projects to divert water and other vital resources from Assyrian to Kurdish communities." These deprivations led to a mass exodus, followed by "the seizure and conversion of abandoned Assyrian property by the local Kurdish population." Turkmen groups report "similar abuses by Kurdish officials, suggesting a pattern of pervasive discrimination, harassment, and marginalization."

Violence against Iraq's Christian community "remains a significant concern, particularly in Baghdad and the northern Kurdish regions," with a pattern of "official discrimination, harassment, and marginalization by KRG officials exacerbating these conditions."[81][82][83] Kurdish groups have been accused of attempting to annex territories belonging to Assyrians, "claiming that these areas are historically Kurdish." Since 2003, "Kurdish peshmerga, security forces, and political parties have moved into these territories, establishing de facto control over many of the disputed areas." Assyrians, Shabak, and Turkomen groups have accused Kurdish forces "of engaging in systematic abuses and discrimination against them to further Kurdish territorial claims." These accusations include "reports of Kurdish officials interfering with minorities' voting rights, encroaching on, seizing, and refusing to return minority land, conditioning the provision of services and assistance to minority communities on support for Kurdish expansion, forcing minorities to identify themselves as either Arabs or Kurds, and impeding the formation of local minority police forces."[84]

Freedom of speech and political freedom

[edit]Kurdish officials in Iraq have accused the ruling Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), led by Masoud Barzani, of "all kinds of intimidation," corruption, and ballot stuffing.[85][75] During the 2005 elections, "Kurdish authorities, tasked with delivering ballot boxes to Assyrian districts in Iraqi Kurdistan, failed to do so, while Assyrian election workers were fired upon and killed." As a consequence, the Assyrian Democratic Movement was marginalized.[86]

The current state of human rights

[edit]Numerous human rights organizations and Shiite officials have raised significant criticisms, alleging that Sunni groups have systematically kidnapped, tortured, and killed Shiites or those they consider enemies. Amnesty International has also extensively criticized the Iraqi government for its handling of the Walid Yunis Ahmad case, in which an ethnically Turkmen journalist from Iraqi Kurdistan was held for ten years without charge or trial.[87]

According to the Human Rights Watch annual report, the human rights situation in Iraq remains deplorable. Since 2015, the country has been embroiled in a bloody armed conflict involving ISIS and a coalition of Kurdish forces, central Iraqi government forces, pro-government militias, and a United States-led international air campaign. The United Nations reported that 3.2 million Iraqis were displaced due to the conflict. Furthermore, the international organization stated that the warring parties employed various methods, including extrajudicial executions, suicide attacks, and airstrikes, which resulted in the deaths and injuries of over 20,000 civilians.[88]

An Amnesty International report concluded that the Peshmerga forces of the semi-autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) were preventing residents of Arab villages and Arab residents of mixed Arab-Kurdish towns from returning to their homes. In some cases, the Peshmerga forces had destroyed or allowed the destruction of homes and property, seemingly to prevent residents from returning in the future. Amnesty reported that Arab houses were often looted, intentionally burned, bulldozed, or blown up after fighting had ended, and the Peshmerga had taken control of these areas. These actions were not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern.

The report emphasized that the forced displacement of Arab residents and the extensive, unlawful destruction of civilian homes and property violated international humanitarian law and should be investigated as war crimes. For example, the village of Tabaj Hamid was completely razed, and in Jumeili, 95% of all walls and structures were destroyed. Amnesty International researchers reported being apprehended by Peshmerga forces, who escorted them out of the area and prevented them from taking photographs.[89][90][91][92]

Amnesty stated that the deliberate demolition of civilian homes is unlawful under international humanitarian law and considered these acts of forced displacement to constitute war crimes.[93] The organization also urged KRG authorities to conduct prompt and independent investigations into all deaths that occurred during protests against the KDP, such as those in October 2015, and to disclose the findings.[94]

Amnesty International criticized the Peshmerga forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Kurdish militias in northern Iraq for bulldozing, blowing up, and burning thousands of homes in what appears to be an effort to uproot Arab communities. The report, Banished and Dispossessed: Forced Displacement and Deliberate Destruction in Northern Iraq, is based on field investigations in Iraq. It stated, “Tens of thousands of Arab civilians who were forced to flee their homes because of fighting are now struggling to survive in makeshift camps in desperate conditions. Many have lost their livelihoods and all their possessions, and with their homes destroyed, they have nothing to return to. By barring the displaced from returning to their villages and destroying their homes, KRG forces are further exacerbating their suffering.” The report provided evidence of forced displacement and large-scale destruction of homes in villages and towns by Peshmerga forces.[95][96][97][98][99]

Human Rights Watch also reported that Kurds denied Arabs the right to return to their homes while allowing Kurds free movement, even permitting Kurds to move into homes that belonged to Arabs.[100] In a 2016 report titled ‘Where Are We Supposed to Go?’: Destruction and Forced Displacement in Kirkuk, Amnesty International documented cases of Kurdish authorities demolishing and bulldozing homes and forcibly displacing hundreds of Arab residents.[101]

In 2005, during a demonstration by the Democratic Shabak Coalition, the KDP opened fire on protestors, killing two Assyrians and wounding several Assyrians and Shabak participants.[102] Additionally, Assyrian groups have accused Kurdish authorities of election rigging in northern Iraq and of preventing Assyrian representation in politics.[103]

The Shabak people have also suffered from discrimination. Hunain al-Qaddo, a Shabak politician, told Human Rights Watch that "the Peshmerga have no genuine interest in protecting his community and that Kurdish security forces are more interested in controlling Shabaks and their leaders than protecting them." He further stated that Shabaks are "suffering at the hands of the Peshmerga and that the Kurdish government refuses to let the Iraqi armed forces protect them or allow them to establish their own Shabak police force to safeguard their community."

Kurdish forces have been implicated in some attacks against Shabaks. In 2008, Mullah Khadim Abbas, the leader of the Shabak Democratic Gathering—a group opposing the incorporation of Shabak villages into the KRG—was killed only 150 meters from a Peshmerga outpost. Before his assassination, Abbas had angered Kurdish authorities by criticizing Shabaks who supported Kurdish agendas and denouncing Kurdish policies that, in his view, undermined the identity of the Shabak community.

In 2009, Shabak lawmaker al-Qaddo survived an assassination attempt in the Nineveh Plains. He told Human Rights Watch that the attackers wore Kurdish security uniforms. Al-Qaddo alleged that the Kurdish government aimed to impose its will on the Shabak and acquire their lands by silencing him.

Shabak leaders have frequently complained about the lack of accountability for killings. In some incidents, the KDP was accused of failing to investigate the deaths of non-Kurdish civilians at the hands of the Peshmerga. Human Rights Watch noted that "the root of the problem is the near-universal perception among Kurdish leaders that minority groups are, in fact, Kurds." The report further stated that Kurdish authorities have sometimes dealt harshly with Yazidi and Shabak individuals who resisted attempts to impose a Kurdish identity on them.[104]

Sectarian warfare in Iraq

[edit]Iraq experienced a state of sectarian civil war from 2006 to 2008. During this period, small groups and militias carried out bombings in civilian areas and assassinations targeting officials at various levels, as well as Shiites and smaller religious minorities. Secular-oriented individuals, officials of the new government, aides to the United States (such as translators), and individuals and families from the country's various religious groups faced violence and death threats.

Refugee response to threats to life

[edit]See also Refugees of Iraq.

As a result of attempted murders and death threats, approximately 2 million Iraqis fled the country, primarily seeking refuge in Syria, Jordan, and Egypt.[105]

Propaganda

[edit]On February 17, 2006, then U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld discussed the emergence of new realities in the media age:[106]

- "In Iraq, for example, the U.S. military command, working closely with the Iraqi government and the U.S. embassy, has sought nontraditional means to provide accurate information to the Iraqi people in the face of aggressive campaign of disinformation. Yet this has been portrayed as inappropriate; for example, the allegations of someone in the military hiring a contractor, and the contractor allegedly paying someone to print a story—a true story—but paying to print a story."

On March 3, 2006, Army General George Casey stated, "The U.S. military plans to continue paying Iraqi newspapers to publish articles favorable to the United States after an inquiry found no fault with the controversial practice." Casey explained that an internal review had concluded the U.S. military was not violating U.S. law or Pentagon guidelines with its information operations campaign. As part of this campaign, U.S. troops and a private contractor wrote pro-American articles and paid to have them published in Iraqi media without attribution.[107]

The legal status of freedom of speech and the press in Iraq remains unclear. While both freedoms are guaranteed in the Iraqi Constitution, they include exemptions for Islamic morality and national security. Additionally, the 1969 Iraqi Criminal Code contains vague prohibitions against using the press or any electronic means of communication for "indecent" purposes.

Women's rights

[edit]

Women in Iraq at the beginning of the 21st century face a status that is influenced by many factors, including wars (most recently the Iraq War), sectarian religious conflict, debates concerning Islamic law and Iraq's Constitution, cultural traditions, and modern secularism. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqi women have been widowed as a result of a series of wars and internal conflicts. Women's rights organizations continue to struggle against harassment and intimidation as they work to promote improvements to women's status in law, education, the workplace, and many other spheres of Iraqi life. According to a 2008 report in the Washington Post, the Kurdistan region of Iraq is one of the few places in the world where female genital mutilation has been rampant.[110] In 2008, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) stated that honor killings are a serious concern in Iraq, particularly in Iraqi Kurdistan.[111] Honor killings are common in the region, and women also face forced and underage marriage, domestic violence, and polygamy issues. Since the early 1990s, several thousand Iraqi Kurdish women have died from self-immolation.[112]

Other human rights

[edit]The United States, through the CPA, abolished the death penalty (which has since been reinstated) and ordered that the Criminal Code of 1969 (as amended in 1985) and the Civil Code of 1974 would be the operating legal system in Iraq. However, there has been some debate regarding the extent to which the CPA rules have been applied.

For example, the Iraqi Criminal Code of 1969 (as amended in 1985) does not prohibit the formation of trade unions, and the Iraqi Constitution promises that such organizations will be recognized (a right under Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights). However, for some reason, the Iraqi courts and special tribunals seem to be operating under a slightly revised version of the 1988 legal code, which means that the 1987 ban on unions might still be in place.

Likewise, while the Iraqi Criminal Code of 1969 or the apparent 1988 edition does not expressly prohibit homosexual relations between consenting adults in private (a right under a United Nations Human Rights Commission ruling in 1994), scattered reports suggest that homosexuality is still being treated as a crime, possibly a capital crime under a 2001 amendment that technically should not exist. For more information on this topic, see Gay rights in Iraq.

Post COVID-19 rights

[edit]During COVID-19, the Iraqi government implemented stricter curfews and limited shopping hours instead of full lockdowns, aiming to keep the economy afloat. However, human welfare significantly worsened due to droughts in the area. The modern government did not provide adequate assistance to the majority of the population during the crisis. All but two refugee camps were closed, and internally displaced people were targeted by armed forces. Many of these displaced families had been fleeing the Syrian civil war. In December and November 2021, heavy rainfall caused flash floods, leading to many families becoming homeless or displaced, both internally and externally.

Notes

[edit]- ^ There have also been accusations that Kurds were rigging votes in Kirkurk in 2005.[40]

- ^ AINA reported that land disputes between Assyrians and Kurds have a long history, and claim that Kurds have used every opportunity to "seize their villages and lands through massacre, systematic killings and intimidation". They claim that this happened during the Kurdish revolt of the 1960s, the Simel massacre of 1933, the First World War and at other times. AINA also reported that textbooks used in Kurdish controlled areas are "replete with Kurdish flags and nationalist poems glorifying Kurdistan", and that only the Kurdish village names are used. AINA also noted that "hundreds of Kurdish families from Iran settled in the Assyrian town of Sarsing".[54] Francis Yusuf Shabo was an Assyrian Christian politician who dealt with complaints by Assyrian Christians regarding villages from which they had been forcibly evicted during the Arabization and subsequently resettled by Arabs and Kurds.[55][56] He was shot dead in Duhok in 1993. Lazar Mikho Hanna (known as Abu Nasir) was another Assyrian Christian politician who was shot dead in 1993 in Duhok. Amnesty International has reported that these killings were attributed to special forces within the KDP, PUK and IMIK.[55] In 1997, two Assyrian politicians, Samir Moshi Murad and Peris Mirza Salyu, were killed near Arbil, by Kurdish students allegedly members of the PUK.[56] In 1999 KDP members were accused of the rape and murder of 21-year old Assyrian woman Helena Sawa.[57] In 2004, a "KDP militia attacked St. John the Baptist Syriac Catholic church in Bakhdida, and residents were severely beaten, finally taken away".[54] In 2008, KRG authorities arrested Assyrian blogger Johnny Khoshaba al-Raykani based on critical articles he had written. Also reported is the arbitrary arrest and detainment of Hazim Nuh, a member of the ADM, Hammurabi Human Rights Organisation, and Tell-Kayf District Council, in 2009.[54] A series of killings of Christians in Mosul was reported in 2008, with HRW and Washington Times writing about reports from Assyrian groups that Kurds may be behind the attacks. Kurdish authorities have denied their involvement.[54] In 2011, radical imams in Zakho, Dohuk Province encouraged Sunni Muslim Kurds to riot and destroy Christian shops selling alcohol and churches and houses. Thirty shops were burned; and many other Christian buildings destroyed[58] The New York Times reported that after Christians had to flee, Christian towns were being seized and occupied by Kurdish forces. Kurdish peshmerga used the fight against ISIL to expand their territory into Christian lands in the Nineveh Plain. Christian militias had to the Kurds for permission to travel in these regions.[59] There were murders and imprisonment of many Assyrians over land disputes in northern Iraq, the rape of Assyrian girls and the assassination of two prominent Assyrians: Francis Shabo and Franso Hariri.[60] Kurds in Zakho in northern Iraq rioted over four days, set dozens of liquor stores alight, attacked an Assyrian church and homes and destroyed property including four hotels, a health club and an Assyrian social club in Dohuk. The KRG has increased Kurdish expansionism at the expense of Assyrian interests. The KRG has systematically intimidated Assyrian politicians and has sought to flood the territory with Kurds and Kurdish security forces with the hope that an increase in the Kurdish populace and a weakening of political will among divided minority groups will allow them to annex the plains.[61] As was reported from the wikileaks cables, continuing Kurdish intimidation continues to be a problem for Iraqi Christians. Assyrians have reported that there is an increasingly bellicose KRG policy as the result of the Kurds, desire not to lose what was gained in terms of self-rule after the first Gulf War. As a result, there is an ongoing trend toward authoritarianism in the KRG, and the Kurds are a highly tribalized society, prone to in-fighting and more Islamic extremism than was currently apparent. Radicals notwithstanding, there is greater tolerance for the Christian faith among Iraqi Arabs than among Iraqi Kurds.[62]

- ^ The "Assyrian Human Rights Report" states among other things that "as far as the Assyrian community in concerned, the most important role remained the adjudication of expropriation of Assyrian lands at the hands of the Kurds in northern Iraq." Kurds subsequently resettled villages illegally from where they had evicted Assyrians, and have not allowed Assyrians to resettle their lands. The report also states that "recent attacks against Assyrian civilians by Kurds in northern Iraq and by others elsewhere in the country have recently increased, and most of the villages have been subsequently reclaimed by Kurds. It also notes that "following the establishment of the a safe Haven further land grabs by Kurds directly or indirectly supported by local Kurdish authorities have led to the expropriation of lands from 52 additional villages in northern Iraq".[73] Assyrian leader Francis Shabo who was working on this issue was later assassinated. The report also said that in spring 1996, "an attempt was made to Kurdify the educational curriculum". Assyrian girls were kidnapped, raped and forcefully married to Kurds. Such incidents include Wassan Michael, an Assyrian girl from Simele who was kidnapped in 1996 and forced to marry one of the Kurdish kidnappers. In 1996 an Assyrian girl was abducted by a Kurd named Mohamed Babakir.[73]

See also

[edit]- Prisoner abuse

- Operation Phantom Fury

- Human rights in pre-Saddam Iraq

- Human rights in Saddam Hussein's Iraq

- 2003 invasion of Iraq

- Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse

- Human Rights Record of the United States

- Country Reports on Human Rights Practices

- Slavery in Iraq

- Gay rights in Iraq

- Refugees of Iraq

- Sectarianism

- Religious war

References

[edit]- ^ "Iraq". Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ NewsHour Extra: Who Are the Iraq Insurgents? - June 12, 2006 Archived June 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "UN News Centre | News Focus: Dark day for UN". Un.org. Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ a b "CBC News Indepth: Iraq". Cbc.ca. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Insurgents kill Bulgarian hostage: Al-Jazeera". CBC News. July 14, 2004. Archived from the original on April 27, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ "Memri Tv". Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ^ "Free Internet Press - Uncensored News for Real People". Freeinternetpress.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "BBC News | Middle East | Captors kill Egypt envoy to Iraq". London: News.bbc.co.uk. July 8, 2005. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ Worth, Robert F. (February 25, 2006). "Muslim Clerics Call for an End to Iraqi Rioting". New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2006.

- ^ "BBC News | Middle East | Russian diplomat deaths confirmed". London: News.bbc.co.uk. June 26, 2006. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ "IRIN Africa | Horn of Africa | HORN OF AFRICA | HORN OF AFRICA: IRIN-HOA Weekly Round-up 355 for 9-15 December 2006 | Other | Weekly". www.irinnews.org. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- ^ "IRIN Middle East | Middle East | Iraq | IRAQ: Analysts say violence will continue to increase | Conflict | Breaking News". www.irinnews.org. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- ^ "Kuna site|Story page|Final death toll of attack at Al-Zafaraniyah : 57 ...8/14/2006". www.kuna.net.kw. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Bloomberg.com: Worldwide". Bloomberg.com. August 14, 2006. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ "Iraq deaths in British custody could see military face legal challenges". Guardian. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Ministry of Defence pays £100,000 to family of drowned Iraqi teenager". Guardian. 21 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Troops cleared over Iraq drowning". BBC News. 6 June 2006. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ "Iraqi, 15, 'drowned after soldiers forced him into canal'". Guardian. 2 May 2006. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Carrell, Severin (1 August 2004). "Hanan's killing has become a symbol of a flawed occupation'". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "British soldier admits war crime". BBC News. 19 September 2006. Archived from the original on 19 September 2006. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- ^ Devika Bhat; Jenny Booth (September 19, 2006). "British soldier is first to admit war crime". Times Online. London. Retrieved 2006-09-23.[dead link]

- ^ "UK soldier jailed over Iraq abuse". BBC News. 30 April 2007. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ "A bloody epitaph to Blair's war". Independent on Sunday. London. 17 June 2007. Archived from the original on June 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ^ "Youth, 19, died at wedding | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ "Video shows killing of 3 Iraqis by US helicopter". The Irish Times. 6 May 2004.

- ^ Raddatz, Martha (9 January 2004). "Rules of Engagement". ABC News. Archived from the original on 19 January 2004.

- ^ "The Apache Killing Video". IndyMedia. 19 January 2004. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ "Experts examine Apache Killing Video". IndyMedia. February 29, 2004. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- ^ "Das Erste - Panorama - Militärexperten beschuldigen US-Soldaten des Mordes". Daserste.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "Nyheterna.se - Video visar hur britter slår irakier". Nyheterna.se. 12 February 2006. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2006-02-12.

- ^ "UK Troops Beating Iraqi Children". February 13, 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-05. [dead link]

- ^ "EastSouthWestNorth: The Wedding Party at Mogr el-Deeb". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "Evidence suggests Haditha killings deliberate: Pentagon source". Associated Press. 2 August 2006. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Gowen, Annie; Asaad Majeed (September 2, 2011). "Iraq to reopen probe of deadly 2006 Ishaqi raid". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Associated Press, Kristin M. Hall (February 2012). "Jury reviews records for soldier's sentencing". Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Bender, Bryan (June 20, 2006). "Army says 3 soldiers shot 3 Iraqis execution-style". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 22, 2006. Retrieved June 20, 2006.

- ^ "IRAQ: HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN IRAQI KURDISTAN SINCE 1991". amnesty. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ a b c UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylym Seekers — United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, August 2007.

- ^ UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylym Seekers — United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, August 2007, see USDOS, 2005 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Iraq,

- ^ UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylym Seekers — United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, August 2007, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link); AFP, Ethnic tensions deepen over vote in northern Iraqi city, 6 February 2006, http://www.institutkurde.org/en/info/index.php?subaction=showfull&id=1107790140&archive=&start_from=&ucat=2&; - ^ UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylym Seekers — United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, August 2007, see AINA, Kurds Block Assyrians, Shabaks From Police Force in Northern Iraq *PIC*, 24 June 2006, "Kurds Block Assyrians, Shabaks from Police Force in Northern Iraq *PIC". Archived from the original on 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2016-12-13.."

- ^ "Kurdish Gunmen Open Fire on Demonstrators in North Iraq". www.aina.org. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

- ^ "Kurdish sub-group demand separate recognition in new Iraq". Archived from the original on 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ "State Department cable details ethnic cleansing by US-backed forces in Iraq". World Socialist Web Site. 16 June 2005. Archived from the original on 2012-04-27. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylym Seekers — United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, August 2007, see Al-Ahram Weekly Online, An Iraqi powderkeg, Issue No. 750, 7–13 July 2005, http://weekly.ahram[permanent dead link]. org.eg/2005/750/re5.htm."

- ^ UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylym Seekers — United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, August 2007, see USDOS, 2005 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Iraq, see above footnote 333. See also: Cordesman, see above footnote 443; Al-Qaddo, see above footnote 209."

- ^ UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylym Seekers — United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, August 2007, Kathleen Ridolfo, Iraq: New Kurdish Administration Comes Under Scrutiny, RFE/RL, 12 May 2006, http://www.rferl.org/featuresarticle/2006/5/4B58E7A7-5456-4D67-A1F1-B5DF2E2[permanent dead link] AD5B4.html.

- ^ Ridolfo, ibid; Nora Bustany, In Releasing Writer, Kurds Ponder Press Freedom, The Washington Post, 7 April 2006, [1] 040602067.html?nav=rss_opinion/columns."[dead link]

- ^ "PYD Impose Kurdish Education Curricula on Assyrians, Arabs in Syria". www.aina.org. Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ "No equal rights - Victims of injustice". www.atour.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ "Assyrians Demand Kurdish Apology for Last Century Killings". rudaw.net. Archived from the original on 2016-11-13. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ "Barzani Calls Assyrian Massacre Victims 'Kurds'". www.aina.org. Archived from the original on 2017-01-07. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ a b "2013 Human Rights Report on Assyrians in Iraq". Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ^ a b c d Iraq — The Struggle to Exist — Rights Situation in the New Iraq http://www.aina.org/reports/acetste.pdf Archived 2016-11-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Amnesty International Country Report, Iraq 1995 and http://www.atour.com/news/assyria/20030617a.html Archived 2016-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b http://www.atour.com/news/assyria/20030617a.html Archived 2016-12-28 at the Wayback Machine Amnesty International Country Report, Iraq 1997

- ^ United States Department of State http://www.aina.org/releases/helena.htm Archived 2016-11-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "The Kurds and Assyrians: Everything You Didn't Know". Archived from the original on 2017-01-10. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ^ Griswold, Eliza (22 July 2015). "Is This the End of Christianity in the Middle East?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ "Assyrian Leaders Have a History of 'Disappearing' in North Iraq". Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ^ "The desperate plight of Iraq's Assyrians and other minorities | Mardean Isaac". TheGuardian.com. 24 December 2011. Archived from the original on 2017-01-11. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ^ "Full-text search". cablegatesearch.wikileaks.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "The Kurds and Assyrians: Everything You Didn't Know". www.aina.org. Archived from the original on 2017-01-10. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ "Mass Graves of Yazidis Killed by the Islamic State Organization or Local Affiliates On or After August 3, 2014" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-10.

- ^ "The betrayal of Shingal". ÊzîdîPress - English. 2015-08-07. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ Reuter, Christoph (2014-08-18). "PKK Assistance for Yazidis Escaping the Jihadists of the Islamic State". Der Spiegel. ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ a b On the Margins of Nations: Endangered Languages and Linguistic Rights. Foundation for Endangered Languages. 2007 Cambridge University Press, Joan A. Argenter, R. McKenna Brown - 2004 -

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Iraq's Minority Crisis and U.S. National Security: Protecting Minority Rights in Iraq". Archived from the original on 2017-01-10. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ a b c "Iraq". Retrieved 2017-06-24.

- ^ Schanzer, Jonathan. (2004) Ansar al-Islam: Back in Iraq Middle East Quarterly

- ^ "From Lingua Franca to Endangered Language The Legal Aspects of the Preservation of Aramaic in Iraq" by Eden Naby, In: On the Margins of Nations: Endangered Languages and Linguistic Rights, Foundation for Endangered Languages. Eds:Joan A. Argenter, R. McKenna Brown PDF Archived 2017-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Assyrian Human Rights Report". Archived from the original on 2016-12-24. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- ^ "Iraq and the Kurds: Confronting Withdrawal Fears". 28 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ a b "Four Myths about the Kurds, Debunked". 4 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2024-01-13. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ "US group accuses Kurds of keeping Yazidi, Christian refugees from their Iraqi homeland". Fox News. 15 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ "Advocates: Kurds Keeping Christians and Yazidis from Going Home". Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ "Senator McCain Sends Letter on Assyrians to Kurdish President". Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-07-08. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "2011 Human Rights Report on Assyrians in Iraq The Exodus from Iraq" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ "United States Commission on International Religious Freedom" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-15. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

- ^ "Iraqi Kurdistan: Not So Democratic". www.aina.org. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

- ^ "ANNUAL REPORT OF THE UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

- ^ "2012 Annual Report". Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Internal Divisions Threaten Kurdish Unity". Archived from the original on 2017-05-18. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ "Iraqi Kurdistan: Not So Democratic". Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ "Walid Yunis Ahmad: Charged After 11 Years of Unlawful Detention". Amnesty International. March 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Iraq - Events of 2015. January 1, 2016. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Banished and Dispossessed — Forced Displacement and Deliberate Destruction in Northern Iraq, a report by Amnesty International, 2016"

- ^ "Report: Kurds displacing Arabs in Iraq in what could be 'war crimes' - the Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ^ "Peshmerga forces from the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Kurdish militias in northern Iraq have bulldozed, blown up and burned down thousands of homes in an apparent effort to uproot Arab communities in revenge for their perceived support for the so-called Islamic State (IS), said Amnesty International in a new report published today". Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

- ^ "Northern Iraq: Satellite images back up evidence of deliberate mass destruction in Peshmerga-controlled Arab villages". 20 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ^ Amnesty — We had nowhere else to go — Syria: 'We had nowhere to go' - Forced displacement and demolitions in Northern Syria By Amnesty International, 13 October 2015, Index number: MDE 24/2503/2015

- ^ Iraq: Kurdistan Regional Government must rein in armed political party militias and investigate killings during protests By Amnesty International, 21 October 2015, Index number: MDE 14/2711/2015

- ^ "Peshmerga forces from the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Kurdish militias in northern Iraq have bulldozed, blown up and burned down thousands of homes in an apparent effort to uproot Arab communities in revenge for their perceived support for the so-called Islamic State (IS), said Amnesty International in a new report published today". Archived from the original on 2016-11-20. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ^ "Northern Iraq: Satellite images back up evidence of deliberate mass destruction in Peshmerga-controlled Arab villages". 20 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ^ "Amnesty: Kurden vertreiben arabische Iraker". kurier.at (in German). 2016-01-20. Archived from the original on 2016-11-20. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Amnesty wirft Peschmerga-Kämpfern Kriegsverbrechen vor | DW | 20.01.2016". DW.COM (in German). Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Neue Vertreibungsvorwürfe gegen Kurden". 21 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-01-24. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ^ "Irakisch-Kurdistan: Araber vertrieben, ausgegrenzt und eingesperrt". Human Rights Watch (in German). 2015-02-25. Archived from the original on 2016-11-20. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Iraq: Kurdish authorities bulldoze homes and banish hundreds of Arabs from Kirkuk". 7 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ^ The Legacy of Iraq by Benjamin Isakhan Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Crisis in Kirkuk: The Ethnopolitics of Conflict and Compromise, Liam Anderson, Gareth Stansfield University of Pennsylvania Press, 123-126

- ^ "On Vulnerable Ground". Human Rights Watch. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ "BBC News | Middle East | Warnings of Iraq refugee crisis". London: News.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-10-28. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Speaker: Donald H. Rumsfeld, Secretary, U.S. Department of DefensePresider: Kenneth I. Chenault, Chairman, American Express Company. "New Realities in the Media Age: A Conversation with Donald Rumsfeld [Rush Transcript; Federal News Service, Inc.] - Council on Foreign Relations". Cfr.org. Archived from the original on 2008-08-10. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Detnews.com | This article is no longer available online". Detnews.com. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change" (PDF). www.unicef.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-26.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation (FGM): A Survey on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice among Households in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region" (PDF). www.unicef.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-07.

- ^ Paley, Amit R. (December 29, 2008). "For Kurdish Girls, a Painful Ancient Ritual: The Widespread Practice of Female Circumcision in Iraq's North Highlights The Plight of Women in a Region Often Seen as More Socially Progressive". Washington Post Foreign Service. p. A09. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Muscati, Samer (22 February 2011). "At a Crossroads". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "Self-immolations on the rise among Iraqi Kurdish women - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

External links

[edit]General human rights

[edit]- Assyrian Human Rights Report

- [2] Human Rights Watch: Background on the Crisis in Iraq (a contents page for the organization's various reports on Iraq, mostly after Saddam's regime fell)

- Iraq Inter-Agency Information & Analysis Unit Reports, Maps and Assessments of Iraq's Governorates from the UN Inter-Agency Information & Analysis Unit

- [3] U.S. Department of State Country Report on Human Rights Practices: Iraq, 2005 (released March 8, 2006)

- [4] Freedom House 2006 report on Iraq

Torture

[edit]- "OneWorld.net's Latest Coverage on Iraq". Archived from the original on 2008-02-02. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Pictures of the abuse by US soldiers, courtesy of The Memory Hole. Note that the full set of pictures has not been released, including the rape of a young Iraqi by a military contractor.

- April 7, 2003 DOD Briefing on Geneva Convention, EPW's and War Crimes at the Wayback Machine (archived January 30, 2006)

- The Guardian: Soldier arrested over Iraqi torture photos (May 31, 2003)

- Washington Post: 'Torture Lite' Takes Hold in War on Terror (March 3, 2004)

- US tactics condemned by British officers (April 21, 2004) (Daily Telegraph)

- CBS 60 minutes II: Abuse Of Iraqi POWs By GIs Probed (April 29, 2004)

- BBC: US acts after Iraq prisoner abuse, (30 April 2004)

- Doubt cast on Iraq torture photos (May 2, 2004) (BBC)

- 13 reasons why this picture may not be all it seems (May 2, 2004) (Daily Telegraph)

- This Is Not A Hoax. I Saw It, I Was There (Answers to some of the objections; May 3, 2004) (The Daily Mirror) (Alternative link)

- A third UK soldier steps up (May 7, 2004) (The Guardian)

- Mirror admits it was "hoaxed" (May 15, 2004) (The Daily Mirror)

- Two Danish physicians attest to British abuse (May 15, 2004) Archived October 23, 2004, at the Wayback Machine (The New Zealand Herald)

- New Details of Prison Abuse Emerge (May 21, 2004)

- Report: Army doctors involved in Abu Ghraib abuse (2004-08-20) (Reuters)

- Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib - Interview with Seymour Hersh by Democracy Now! on September 14, 2004.

- Journalists Among Those Abused by US Troops (IFEX)

- U.S. State Department on Iraq Human rights in 2004 (released 2005) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices section on Iraq. 460 KB in size for the Iraq portion alone. HTML. One page. No pictures, all English text.

- Editorial: Patterns of Abuse, New York Times, May 23, 2005

- UN raises alarm on death squads and torture in Iraq (Reuters, September 8, 2005)

- US Troops Seize Award-Winning Iraqi Journalist, The Guardian, January 9, 2006

- Thank You Joe Darby – A site for expressions of support for Joe Darby, the soldier that exposed the graphic photos and video and brought the Abu Ghraib prison scandal to light.

- Iraq general's killer reprimanded, BBC, January 24, 2006

- Mild Penalties in Military Abuse Cases, Los Angeles Times, January 25, 2006

Death Squads

[edit]- "The Salvador Option". Archived from the original on 2005-01-14. Retrieved 2006-05-12., Newsweek, January 14, 2005

- Sunni men in Baghdad targeted by attackers in police uniforms, Knight Ridder, June 28, 2005

- 539 Bodies Found in Iraq Since April, AP, October 7, 2005

- Ex-PM: Abuse as bad as Saddam era, CNN, November 27, 2005

- Killings Linked to Shiite Squads in Iraqi Police Force, LA Times, November 29, 2005