| Jahanara Begum | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shahzadi of the Mughal Empire | |||||

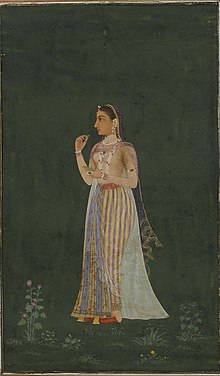

Begum aged 18, painting dated 1632 | |||||

| Padshah Begum | |||||

| 1st reign | 17 June 1631 – 31 June 1658 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mumtaz Mahal | ||||

| Successor | Roshanara Begum | ||||

| 2nd reign | 1669 – 16 September 1681 | ||||

| Predecessor | Roshanara Begum | ||||

| Successor | Zinat-un-Nissa | ||||

| Born | 23 March 1614[1] Ajmer, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Died | 16 September 1681 (aged 67) Delhi, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Burial | Nizamuddin Dargah, Delhi | ||||

| |||||

| House | Timurid | ||||

| Father | Shah Jahan | ||||

| Mother | Mumtaz Mahal | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Jahanara Begum (23 March 1614 – 16 September 1681) was a princess of the Mughal Empire. She was the second and the eldest surviving child of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal.

After Mumtaz Mahal's untimely death in 1631, the 17-year-old Jahanara was entrusted with the charge of the royal seal and conferred the title of Padshah Begum (First lady) of the Mughal Empire, even though her father had three surviving wives. She was Shah Jahan's favorite daughter and she wielded major political influence during her father's reign, and has been described as "the most powerful woman in the empire" at the time.[2]

Jahanara was an ardent partisan of her brother, Dara Shikoh, and supported him as her father's chosen successor. During the war of succession which took place after Shah Jahan's illness in 1657, Jahanara sided with the heir-apparent Dara and joined her father in Agra Fort, where he had been placed under house arrest by Aurangzeb. When Aurangzeb ascended to the throne, Jahanara was replaced by her younger sister, Roshanara as Padshah Begum. A devoted daughter, she took care of Shah Jahan until his death in 1666. Later, Jahanara reconciled with Aurangzeb who gave her the title 'Empress of Princesses' and replaced her younger sister, Princess Roshanara Begum, as the First Lady.[3] Jahanara died during Aurangzeb's reign. She is known for her written works as well, which continues to be a primary way in which her presence in Sufism survives into today. She is well known for a biography of Sheikh Mu’in ad’-Din Chishti, ‘Munis al arwah’ whom she believed to have been the highest of the Sufi saints in India and her spiritual master, despite having lived four centuries before her.[4]

Early life and education

[edit]Jahanara's early education was entrusted to Sati al-Nisa Khanam, the sister to Jahangir's poet laureate, Talib Amuli. Sati al-Nisa was known for her knowledge of the Qur'an and Persian literature, as well as for her knowledge of etiquette, housekeeping, and medicine. She also served as principal lady-in-waiting to her mother, Mumtaz Mahal.[5]

Many of the women in the imperial household were accomplished at reading, writing poetry and painting. They also played chess, polo and hunted outdoors. The women had access to the late Emperor Akbar's library, full of books on world religions, and Persian, Turkish and Indian literature.[6] Jahanara was no exception.

From a carefree girl, she was pushed into government politics, overseeing domestic and international trade, and even mediating courtiers and foreigners to communicate with the emperor, and was involved in the tasks of resolving family disputes. Upon the death of Mumtaz Mahal in 1631, Jahanara, aged 17, took the place of her mother as First Lady of the Empire, despite her father having three other wives.[7] In addition to caring for her younger brothers and sisters, she was also a good caretaker of her father.

One of her tasks after the death of her mother was to oversee, with the help of Sati al-Nisa, the betrothal and wedding of her brother, Dara Shikoh to Nadira Banu Begum, which was originally planned by Mumtaz Mahal, but postponed by her death.

Her father frequently took her advice and entrusted her with the charge of the Imperial Seal. Having the right to issue farmans [clarification needed] and nishans [clarification needed], she was given the greatest and highest rank in the harem. She also attended councils and discussed important aspects of state and governance from behind her curtained seat. The state nobles and kings or foreign ambassadors, whether commercial or political, sought her intervention before the emperor. Her word became so powerful that it was said that it could change the fortunes of people. As French traveller and physician François Bernier writes in his memoirs,Travels in the Mogul Empire,

"Shah Jahan reposed unbounded confidence in his favourite child; she watched over his safety, and so cautiously observant, that no dish was permitted to appear upon the royal table which had not been prepared under her superintendence."

In 1644, when Aurangzeb angered his father, the Badshah, Jahanara interceded on her brother's behalf and convinced Shah Jahan to pardon him and restore his rank.[8] Shah Jahan's fondness for his daughter was reflected in the multiple titles that he bestowed upon her, which included: Sahibat al-Zamani (Lady of the Age), Padishah Begum (Lady Emperor), and Begum Sahib (Princess of Princesses).

Her power was such that, unlike the other imperial princesses, she was allowed to live in her own palace, outside the confines of the Agra Fort. There, she held her own court where she entertained nobles, ministers, officers, clerics and ambassadors, and discussed government affairs or their requests. Foreign trade was known to be an aspect of the empire which felt her influence. It is recorded that the Dutch embassy, in attempting to get permission for trade, had taken note of the importance of Jahanara’s approval, in swaying her father Shah Jahan.[9] In addition to this, she often travelled from the capital, accepting many beggars and petitioners from the people and issued Hukm [clarification needed] or Farman [clarification needed] to meet the needs of society.[10]

In March 1644,[11] just days after her thirtieth birthday, Jahanara suffered serious burns on her body and almost died of her injuries. Shah Jahan ordered that vast sums of alms be given to the poor, prisoners be released, and prayers offered for the recovery of the princess. Aurangzeb, Murad, and Shaista Khan returned to Delhi to see her.[12][13] Accounts differ as to what happened. Some say Jahanara's garments, doused in fragrant perfume oils, caught fire.[13] Other accounts assert that the princess' favorite dancing woman's dress caught fire and the princess, coming to her aid, burnt herself on the chest.[14]

During her illness, Shah Jahan was so concerned about the welfare of his favourite daughter, that he made only brief appearances at his daily durbar in the Diwan-i-Am.[15] Royal physicians failed to heal Jahanara's burns. A Persian doctor came to treat her, and her condition improved for a number of months, but then, there was no further improvement until a royal page named Arif Chela mixed an ointment that, after two more months, finally caused the wounds to close. A year after the accident, Jahanara fully recovered.[16]

After the accident, the princess went on a pilgrimage to Moinuddin Chishti's shrine in Ajmer.[citation needed]

After her recovery, Shah Jahan gave Jahanara rare gems and jewellery, and bestowed upon her the revenues of the port of Surat.[10] She later visited Ajmer, following the example set by her great-grandfather Akbar.[17]

Wealth and charity

[edit]In honor of his coronation, on 6 February 1628,[18] Shah Jahan awarded his wife, Mumtaz Mahal, Jahanara's mother, the title of Padshah Begum and 200,000 ashrafis (Persian gold coins worth two Mohurs), 600,000 rupees and an annual privy purse of one million rupees. Moreover, Shah Jahan presented Mumtaz with jewels worth five million rupees. Jahanara was given the title of Begum Sahiba and received 100,000 ashrafis, 400,000 rupees and an annual grant of 600,000 and she was also awarded jewels worth two million and five hundred thousand rupees.[19][20] Upon Mumtaz Mahal's death, her personal fortune was divided by Shah Jahan between Jahanara Begum (who received half) and the rest of Mumtaz Mahal's surviving children.[21]

Jahanara was allotted income from a number of villages and owned several gardens, including, Bagh-i-Jahanara, Bagh-i-Nur and Bagh-i-Safa.[22] "Her jagir included the villages of Achchol, Farjahara and the Sarkars of Bachchol, Safapur and Doharah. The pargana of Panipat was also granted to her."[23] As mentioned above, she was also given the prosperous city of Surat.

Her great-grandmother, Mariam-uz-Zamani established an international trading business in the Mughal Empire and owned several trading ships like Rahīmī and Ganj-I-Sawai, which dealt between Surat and the Red Sea trading silk, indigo and spices. Nur Jahan continued the business, trading in indigo and cloth. Later, Jahanara continued the tradition.[24] She owned a number of ships and maintained trade relations with the English and the Dutch.[25]

Jahanara was known for her active participation in looking after the poor and financing the building of mosques.[26] When her ship, the Sahibi was to set sail for its first journey (on 29 October 1643), she ordered that the ship make its voyage to Mecca and Medina and, "... that every year, fifty koni (One Koni was 4 Muns or 151 pounds) of rice should be sent by the ship for distribution among the destitute and needy of Mecca."[27]

As the de facto Primary Queen of the Mughal empire, Jahanara was responsible for charitable donations. She organized almsgiving on important state holidays and religious festivals, supported famine relief and pilgrimages to Mecca.[28]

Jahanara made important financial contributions in the support of learning and arts. She supported the publication of a series of works on Islamic mysticism, including commentaries on Rumi's Mathnavi, a very popular mystical work in Mughal India.[29]

Sufism

[edit]Along with her brother Dara Shikoh, she was a disciple of Mullah Shah Badakhshi, who initiated her into the Qadiriyya Sufi order in 1641. Jahanara Begum made such progress on the Sufi path that Mullah Shah would have named her his successor in the Qadiriyya, but the rules of the order did not allow this.[17]

She wrote a biography of Moinuddin Chishti, the founder of the Chishti Order in India, titled Mu'nis al-Arwāḥ (Arabic: مونس الارواح, lit. 'confidante of souls'), as well as a biography of Mullah Shah, titled Risālah-i Ṣāḥibīyah, in which she also described her initiation by him.[30] Her biography of Moinuddin Chishti is highly regarded for its judgment and literary quality. In it, she regarded him as having initiated her spiritually four centuries after his death, described her pilgrimage to Ajmer, and spoke of herself as a faqīrah to signify her vocation as a Sufi woman.[31]

An aspect of her Sufi work also included an autobiographical narrative, detailing her thoughts and experiences, titled Sahibiya (The Lady’s Treatise), and contained information pertaining to her spiritual experience, her search for a Sufi master and her transitioning to the Qadiri order in Lahore. This transition was a complicated decision to make: “It occurred to me that I was a disciple of the Chishti order, but now that I was entering the Qadiri order, would there be conflict in me?”[32]

Jahanara Begum stated that she and her brother Dārā were the only descendants of Timur to embrace Sufism.[33] (However, Aurangzeb was spiritually trained as a follower of Sufism as well.) As a patron of Sufi literature, she commissioned translations and commentaries of many works of classic Sufi literature.[34]

War of Succession

[edit]

Shah Jahan fell seriously ill in 1657. A war of succession broke out among his four sons, Dara Shikoh, Shah Shuja, Aurangzeb and Murad Baksh.[35]

During the war of succession, Jahanara supported her brother Dara Shikoh, the eldest son of Shah Jahan. When Dara Shikoh's generals sustained a defeat at Dharmat (1658) at the hands of Aurangzeb, Jahanara wrote a letter to Aurangzeb and advised him not to disobey his father and fight with his brother. She was unsuccessful. Dara was badly defeated in the Battle of Samugarh (29 May 1658), and fled towards Delhi.[36]

Shah Jahan did everything he could to stop the planned invasion of Agra. He asked Jahanara to use her diplomacy to convince Murad and Shuja not to throw their weight on the side of Aurangzeb.[37]

In June 1658, Aurangzeb besieged his father Shah Jahan in the Agra Fort, forcing him to surrender unconditionally, by cutting off the water supply. Jahanara came to Aurangzeb on 10 June, proposing a partition of the empire. Dara Shikoh would be given the Punjab and adjoining territories, Shuja would get Bengal, Murad would get Gujarat, Aurangzeb's son Sultan Muhammad would get the Deccan, and the rest of the empire would go to Aurangzeb. Aurangzeb refused Jahanara's proposition on the grounds that Dara Shikoh was an infidel.[38]

On Aurangzeb's ascent to the throne, Jahanara joined her father in imprisonment at the Agra Fort, where she devoted herself to his care until his death in 1666. Her rival and younger sister, Roshanara, replaced her as Padshah Begum and Begum Sahib, and took over the control of the imperial family and palace thanks to the assistance she had rendered to Aurangzeb during the war of succession.[39][40]

After the death of their father, Jahanara and Aurangzeb reconciled. He restored her former titles to her; Padshah Begum (Lady Emperor or Grand Empress), and Begum Sahib (Princess of Princesses), and bestowed upon her a new title, Shahzadi Sahib (Empress of Princesses). Again, the control of the Khāndān-e-Shahi (royal family) and the Zenana (harem) was entrusted to her. Jahanara replaced Roshanara as the First Lady. As the first lady of his court, her annual allowance was raised from Rs 1 million rupees (during the reign of Shah Jahan) to Rs 1.7 million. In addition, Aurangzeb again gave her the revenue of the port of Surat and a grand mansion in Delhi, where Aurangzeb would spend hours conversing with her. Aurangzeb respected her and sought her counsel in matters of state and public welfare. She never shied from arguing with the Emperor in order to prove her point, especially when it concerned his enforced austerity measures or his practice of religious intolerance.[3]

Jahanara re-entered politics and was influential in various important matters and had certain special privileges which other women did not possess: an independent life with a private palace of her own, the power to issue Hukm or Farman (an imperial order that was only the emperor's right), to attend the council (shura or diwan), to receive audiences in her palace, and to mediate between officers, politicians, and foreign kings and the emperor. She also argued against Aurangzeb's strict regulation of public life in accordance with his conservative religious beliefs, and his decision in 1679 to restore the poll tax on non-Muslims, which she believed would alienate his Hindu subjects. She publicly quarreled with him on these issues and criticised him for his policy.[41]

Relationship with Shah Jahan

[edit]Jahanara’s influence in Mughal administration resulted in several rumors and accusations of an incestuous relationship with her father, Shah Jahan.[42][43] Such accusations have been dismissed by modern historians as gossip, as no witness of an incident has been mentioned.[44]

Historian K. S. Lal also dismisses such claims as rumors, propagated by courtiers and mullahs. He cites Aurangzeb's confining of Jahanara in the Agra Fort with the royal prisoner and gossip magnifying a rumor.[45]

Several contemporary travelers have mentioned such accusations. Francois Bernier, a French physician, mentions rumors of an incestuous relationship being propagated in the Mughal Court.[46] However, Bernier did not mention witnessing such a relationship.[47] Niccolao Manucci, a Venetian traveler, dismisses such accusations by Bernier as gossip and "The talk of the Low People".[42][48]

Burial

[edit]

Jahanara had her tomb built during her lifetime. It is constructed entirely of white marble with a screen of trellis work, open to the sky.[49]

Upon her death, Aurangzeb gave her the posthumous title, Sahibat-uz-Zamani (Mistress of the Age).[50] Jahanara is buried in a tomb in the Nizamuddin Dargah complex in New Delhi, which is considered "remarkable for its simplicity". The inscription on the tomb reads as follows:

بغیر سبزہ نہ پو شد کسے مزار مرا

کہ قبر پوش غریباں ہمیں گیاہ و بس است

Allah is the Living, the Sustaining.

Let no one cover my grave except with greenery,

For this very grass suffices as a tomb cover for the poor.

The mortal simplistic Princess Jahanara,

Disciple of the Khwaja Moin-ud-Din Chishti,

Daughter of Shah Jahan the Conqueror

May Allah illuminate his proof.

1092 [1681 AD]

Architectural legacy

[edit]Jahanara Begum's caravanserai that formed the original Chandni Chowk, from Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalf's 1843 album.

In Agra, she is best known for sponsoring the building of the Jami Masjid or Friday Mosque in 1648, in the heart of the old city.[51] The Mosque was funded entirely by Jahanara, using her personal allowance.[52] In addition to this mosque, she also financed the construction of the Mulla Shah mosque which is located in Srinagar.[53] She founded a madrasa, which was attached to the Jama Masjid, for the promotion of education.[54] She also funded the making of a garden in Kashmir, she was a benefactor of the people.[55]

She also made a significant impact on the landscape of the capital city of Shahjahanabad. Of the eighteen buildings in the city of Shahjahanabad commissioned by women, Jahanara commissioned five. All of Jahanara's building projects were completed around the year 1650, inside the city walls of Shahjahanabad. The best known of her projects was Chandni Chowk, the main street in the walled city of Old Delhi.

She constructed an elegant caravanserai on the East side of the street with gardens in the back. Herbert Charles Fanshawe, in 1902, mentions about the serai:

- "Proceeding up the Chandni Chowk and passing many shops of the principal dealers in jewels, embroideries, and other products of Delhi handicrafts, the Northbrook Clock Tower and the principal entrance to the Queen's Gardens are reached. The former is situated at the site of the Karavan Sarai of the Princess Jahanara Begum (p. 239), known by the title of Shah Begum. The Sarai, the square in front of which projected across the street, was considered by Bernier one of the finest buildings in Delhi, and was compared by him with the Palais Royal, because of its arcades below and rooms with a gallery in front above."[56]

The serai was later replaced by[57] a building, now known as the Town Hall, and the pool in the middle of the square was replaced by a grand clock tower (Ghantaghar).

In popular culture

[edit]- Indian filmmaker F. R. Irani made Jahanara (1935), an early talkie film about her.[58]

- Her early life is depicted in The Royal Diaries book series as Jahanara: Princess of Princesses, India - 1627 by Kathryn Lasky.

- Jahanara is the protagonist of the novel Beneath a Marble Sky (2013) by John Shors.

- She is the main character in the novel Shadow Princess (2010) written by Indu Sundaresan.

- Jahanara is also the main character in Jean Bothwell's An Omen for a Princess (1963).

- She is also the protagonist in Ruchir Gupta's historical novel Mistress of the Throne (2014).

- Madhubala, Mala Sinha and Manisha Koirala have portrayed the role of Jahanara in their respective films, namely Mumtaz Mahal (1944), Jahan Ara (1964) and Taj Mahal: An Eternal Love Story (2005).

- Jahanara is a main character of the 2017 alternate history novel 1636: Mission To The Mughals and the 2021 follow up novel 1637: The Peacock Throne from the Ring of Fire Book series.

- Jahan Ara, a character inspired from the historical figure, is the main character of the 2022 Pakistani historical drama series "Badshah Begum (TV series)" played by Zara Noor Abbas, produced by Momina Duraid and Rafay Rashidi under the banner of MD Productions, HumTv.

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Jahanara Begum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Literature

[edit]- Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal Throne (paperback) (First ed.). London: Phoenix. pp. 555 pages. ISBN 978-0-7538-1758-2.

- Preston, Diana & Michael (2007). A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time (Hardback) (First ed.). London: Doubleday. pp. 354 pages. ISBN 978-0-385-60947-0.

- Lasky, Kathryn (2002). The Royal Diaries: Jahanara, Princess Of Princesses (Hardback) (First ed.). New York: Scholastic Corporation. pp. 186 pages. ISBN 978-0439223508.

References

[edit]- ^ Lal, K.S. (1988). The Mughal harem. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. p. 90. ISBN 9788185179032.

- ^ ASHER, CATHERINE; Asher, Catherine Ella Blanshard; Asher, Catherine Blanshard; Asher, Catherine B. (1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. p. 265. ISBN 9780521267281.

- ^ a b Preston, page 285.

- ^ Lambert-Hurley, Siobhan (2022). Three Centuries of Travel Writing By Muslim Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ^ Nicoll, Fergus (2009). Shah Jahan. London: Haus Publishing. p. 88.

- ^ Anantha Raman, Sita (2009). Women in India: a Social and Cultural History. Santa Barbara: Praeger. pp. 16 (vol. 2).

- ^ Preston, page 176.

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17 Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. p. 129. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ Misra, Rekha (1967). Women of Mughal India. Munshiram Manoharlal.

- ^ a b Preston, page 235.

- ^ "The Biographical Dictionary of Delhi – Jahanara Begum, b. Ajmer, 1614–1681". Thedelhiwalla.com. 14 July 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. pp. 120–121. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ a b Gascoigne, Bamber (1971). The Great Moghuls. New Delhi: Time Books International. p. 201.

- ^ Irvine, William (trans.) (1907). Storia Do Mogor or Mogul India 1653–1708 by Niccolao Manucci Venetian. London: Murray. pp. 219 (vol. 1) – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gascoigne, Bamber (1971). The Great Moghuls. New Delhi: Time Books International. p. 202.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal throne: the saga of India's great emperors. London: Phoenix. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-7538-1758-2.

- ^ a b Schimmel, Annemarie (1997). My Soul Is a Woman: The Feminine in Islam. New York: Continuum. p. 50. ISBN 0-8264-1014-6.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal throne: the saga of India's great emperors. London: Phoenix. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-7538-1758-2.

- ^ Lal, Muni (1986). Shah Jahan. Delhi: Vikas. pp. 100–101.

- ^ Nicoll, Fergus (2009). Shah Jahan. London: Haus Publishing. p. 158.

- ^ Preston, page 175.

- ^ Taher, Mohamed, ed. (1997). Mughal India. Delhi: Anmoi. p. 53.

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu women in the 16th and 17th centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. pp. 124–125. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ Gascoigne, Bamber (1971). The Great Mughals. New Delhi: Time Books International. p. 165.

- ^ Neth, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindi Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. p. 125. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ "Jahanara". WISE Muslim Women. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Moosvi, Shireen (2008). People, Taxation, and Trade in Mughal India. Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-19-569315-7.

- ^ Nicoll, Fergus (2009). Shah Jahan. London: Haus Publishing. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-906598-18-1.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (2004). The Empire of the great Mughals: history, art and culture. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 266. ISBN 1-86189-185-7.

- ^ Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas (1983). A History of Sufism in India. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Mushiram Manoharlal. p. 481. ISBN 81-215-0038-9.

- ^ Helminski, Camille Adams (2003). Women of Sufism: A Hidden Treasure. Boston: Shambhala. p. 129. ISBN 1-57062-967-6.

- ^ Lambert-Hurley, Siobhan (2022). Three Centuries of Travel Writing By Muslim Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ^ Hasrat, Bikrama Jit (1982). Dārā Shikūh: Life and Works (second ed.). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 64.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1997). My Soul Is a Woman: The Feminine in Islam. New York: Continuum. p. 51. ISBN 0-8264-1014-6.

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. p. 125. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. p. 130. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ Lal, Muni (1986). Shah Jahan. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House. p. 318.

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. p. 131. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ "Tomb of Begum Jahanara". Delhi Information. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1989). Studies in Aurangzeb's Reign. London: Sangam Books Ltd. p. 107.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal throne: the saga of India's great emperors. London: Phoeniz. pp. 401–402. ISBN 978-0-7538-1758-2.

- ^ a b Banerjee, Rita (7 July 2021), "Women in India: The "Sati" and the Harem", India in Early Modern English Travel Writings, Brill, pp. 173–208, ISBN 978-90-04-44826-1, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ Bano, Shadab (2013). "Piety and Pricess Jahanara's Role in the Public Domain". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 74: 245–250. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44158822.

- ^ Banerjee, Rita (7 July 2021), "Women in India: The "Sati" and the Harem", India in Early Modern English Travel Writings, Brill, pp. 173–208, ISBN 978-90-04-44826-1, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ Lal, Kishori Saran, ed. (1988), "The Charge of Incest", The Mughal Harem, Adithya Prakashan, pp. 93–94

- ^ Constable, Archibald, ed. (1916), "Begum Saheb", Travels in Mogul India, Oxford University Press, p. 11

- ^ Manzar, Nishat (31 March 2023), "Looking Through European Eyes: Mughal State and Religious Freedom as Gleaned from The European Travellers' Accounts of the Seventeenth Century", Islam in India, London: Routledge, pp. 121–132, doi:10.4324/9781003400202-9, ISBN 978-1-003-40020-2, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ Irvine, William, ed. (1907), "Begum Saheb", Storia Do Mogor Vol 1, Oxford University press, pp. 216–217

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. p. 137. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ Preston, page 286.

- ^ "Jami Masjid Agra – Jami Masjid at Agra – Jami Masjid of Agra India". Agraindia.org.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. pp. 204–205. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ Lambert-Hurley, Siobhan (2022). Three Centuries of Travel Writing By Muslim Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ^ Nath, Renuki (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu Women in the 16th and 17th Centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications. p. 136. ISBN 81-210-0241-9.

- ^ Lambert-Hurley, Siobhan (2022). Three Centuries of Travel Writing By Muslim Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ^ Fanshawe, H.C. (1902). Delhi Past and Present. J. Murray. p. 52. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Khandekar, Nivedita (8 December 2012). "Landmark building with uncertain fate". Hindustan Times. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 9780851706696. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Sarker, Kobita (2007). Shah Jahan and his paradise on earth : the story of Shah Jahan's creations in Agra and Shahjahanabad in the golden days of the Mughals. Kolkata: K.P. Bagchi & Co. p. 187. ISBN 978-81-7074-300-2. OCLC 176865104.

- ^ Sarker (2007, p. 187)

- ^ Mehta, J. L. (1986). Advanced study in the history of medieval India. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers. ISBN 81-207-0298-0. OCLC 1007201916.

- ^ Mehta (1986, p. 418)

- ^ Thackeray, Frank W.; Findling, John E. (2012). Events that formed the modern world : from the European Renaissance through the War on Terror. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-59884-902-8. OCLC 828682002.

- ^ Thackeray & Findling (2012, p. 254)

- ^ a b Mehta (1986, p. 374)

- ^ * Mukherjee, Soma (2001). Royal Mughal ladies and their contributions. New Delhi: Gyan Pub. House. p. 128. ISBN 81-212-0760-6. OCLC 49618757.

- ^ Mukherjee (2001, p. 128)

- ^ Subhash Parihar, Some Aspects of Indo-Islamic Architecture (1999), p. 149

- ^ Shujauddin, Mohammad; Shujauddin, Razia (1967). The Life and Times of Noor Jahan. Caravan Book House. p. 1.

- ^ Ahmad, Moin-ud-din (1924). The Taj and Its Environments: With 8 Illus. from Photos., 1 Map, and 4 Plans. R. G. Bansal. p. 101.