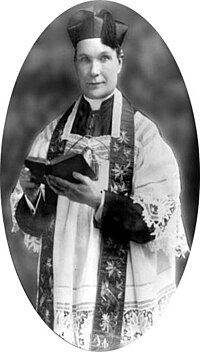

James Coyle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | James Edwin Coyle March 23, 1873 |

| Died | August 11, 1921 (aged 48) Birmingham, Alabama, United States |

| Education | Mungret College, Limerick Pontifical North American College |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| Ordained | May 30, 1896 |

James Edwin Coyle (March 23, 1873 – August 11, 1921) was a Catholic priest who was murdered in Birmingham, Alabama, by a Ku Klux Klan member for performing an interracial marriage.

Biography

[edit]James Coyle was born in Drum, County Roscommon, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, now modern day Ireland, to Owen Coyle and his wife Margaret Durney.[1] He attended Mungret College in Limerick and the Pontifical North American College in Rome, and was ordained a priest at age 23 on May 30, 1896.

Later that year, he sailed with another priest, Father Michael Henry, to Mobile, Alabama, and served under Bishop Edward Patrick Allen. He became an instructor, and later rector, of the McGill Institute for Boys. In 1904 Bishop Allen appointed Coyle to succeed Patrick O'Reilly as pastor of St. Paul's Church (later Cathedral) in Birmingham, where he was well received and loved by the congregation.[2] Father Coyle was the Knights of Columbus chaplain of Birmingham, Alabama Council 635.[3]

Murder

[edit]On August 11, 1921, Father Coyle was shot in the head on the porch of St. Paul's Rectory by E. R. Stephenson, a Southern Methodist Episcopal minister and a member of the Ku Klux Klan. There were many witnesses.[4] The murder occurred just hours after Coyle had performed a secret wedding between Stephenson's daughter, Ruth, and Pedro Gussman, a Puerto Rican whom she had met while he was working at Stephenson's house five years earlier. Gussman had also been a customer at Stephenson's barber shop. Several months before the wedding, Ruth had converted to Catholicism.[5]

Father Coyle was buried in Birmingham's Elmwood Cemetery.[6]

Trial and aftermath

[edit]Stephenson was charged with Father Coyle's murder. The Ku Klux Klan paid for the defense; of the five lawyers, four were Klan members. The case was assigned to the Alabama courtroom of Judge William E. Fort, a Klansman. Hugo Black, a future Justice of the Supreme Court and a future Klansman, was also one of the defense attorneys.[5] The Birmingham News called it the biggest trial in Alabama history.[7]

The defense team took the unusual step of entering a dual plea of "not guilty and not guilty by reason of insanity", essentially arguing that the shooting was in self-defense, and arguing that at the time of the shooting, Stephenson was suffering from "temporary insanity".[8] Stephenson was acquitted by one juror's vote. One of Stephenson's attorneys responded to the prosecution's assertion that Gussman was of "proud Castilian descent" by stating that "he has descended a long way".[9]

The outcome of the murder trial of Father Coyle's assassin had a chilling impact on Catholics, who were the targets of Klan violence for many years to come.[10] Nevertheless, by 1941, a Catholic writer in Birmingham would write that "the death of Father Coyle was the climax of the anti-Catholic feeling in Alabama. After the trial, there followed such a strong feeling of revulsion among the right-minded who before had been bogged down in blindness and indifference that slowly and almost unnoticeably the Ku Klux Klan and their ilk began to lose favor among the people".[11]

Legacy

[edit]On February 22, 2012, Bishop William H. Willimon of the North Alabama Conference of the United Methodist Church presided over a service of reconciliation and forgiveness at Highlands United Methodist Church in Birmingham.[12]

On August 11, 2021, the 100th anniversary of the murder of Coyle, a centennial memorial Mass was held in Coyle's honor at St Paul's Cathedral.[13]

In popular media

[edit]- In 2010, Coyle's great-nephew, Pat Shine, produced a documentary about the murder, A Cross in Alabama.[12][14]

- In 2021, Coyle's grand-niece, Sheila Killian, wrote and published Something Bigger, telling the story of his sister, Marcella Coyle, and her relationship with her brother as well as their interactions with the world around them.[15]

References

[edit]- References

- ^ Community of Drum 2010.

- ^ Davies 2010b, p. 31.

- ^ "The Father James E. Coyle Memorial Project". The Father James E. Coyle Memorial Project. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Sharon Davies, "Tragedy in Birmingham", Columbia Magazine, vol. 90, no. 3 (March 2010), p. 31.

- ^ a b "Remembering A Murdered Birmingham Priest For His Faith And Courage". WBHM 90.3. 2021-08-13. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ Lovett, Rose Gibbons (1980). The Catholic Church in the Deep South: The Diocese of Birmingham in Alabama, 1540-1976. The Diocese.

- ^ Pryor, Jr, William H. (February 2014). "The Murder of Father James Coyle, the Prosecution of Edwin Stephenson, and the True Calling of Lawyers". Notre Dame Journal of Law, Politics, and Public Policy. 20.

- ^ Davies 2010a, p. 215.

- ^ Davies 2010a, p. 275.

- ^ "The Catholic Priest Killed by the Klan for Performing an Interracial Marriage". 20 February 2018.

- ^ McGough, Helen (1941-08-01). "Things I Remember About Father Coyle, His Death, Twenty Years Afterwards". Catholic Weekly. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ a b "Bishop Willimon to lead Ash Wednesday Service of Repentance and Reconciliation". www.umcna.org. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ https://www.wvtm13.com/article/birmingham-remembers-father-james-coyle-on-the-100th-anniversary-of-his-death/37286244

- ^ "Drum native to feature on RTÉ tonight – Drum.ie". Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ Killian, Sheila (Jul 20, 2021). "Murdered by the Ku Klux Klan: The story of my granduncle, a priest, in Alabama in 1921". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- Works cited

- Davies, Sharon (2010). Rising Road: A True Tale of Love, Race, and Religion in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537979-2.

- Davies, Sharon (March 2010). "Tragedy in Birmingham". Columbia Magazine. 90 (3).

- "Fr James Coyle". Community of Drum. 20 March 2010. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Beecher, L. T. (September 1921). "The Passing of Father Coyle". Catholic Monthly. 12.

- Davies, Sharon (2010). Rising Road: A True Tale of Love, Race, and Religion in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537979-2.

- Garrison, Greg (20 August 2006). "Burial site set for priest Klansman killed in '21". The Birmingham News.

- Remillard, Arthur (2011). Southern Civil Religions: Imagining the Good Society in the Post-Reconstruction Era. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-4139-2.