James William Jackson | |

|---|---|

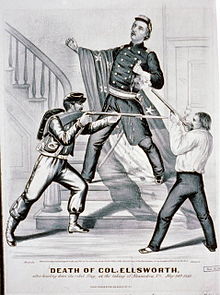

James Jackson shooting Col. Ellsworth | |

| Born | March 6, 1823 Fairfax County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | May 24, 1861 (aged 38) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Occupation | Proprietor of the Marshall House |

| Known for | Ardent secessionist |

James William Jackson (March 6, 1823 – May 24, 1861) was an ardent secessionist and the proprietor of the Marshall House, an inn located in the city of Alexandria, Virginia, at the beginning of the American Civil War. He is known for flying a large Confederate flag – the "Stars and Bars" variant – atop his inn that was visible to President Abraham Lincoln from Washington, D.C., and for killing Col. Elmer Ellsworth in an incident that marked the first conspicuous casualty and the first killing of a Union officer in the Civil War. Jackson was killed immediately after he killed Ellsworth. While losing their lives, both gained fame as martyrs to their respective causes.

The incident

[edit]During the month that Virginia voters contemplated whether to follow the recommendation of the Virginia Secession Convention, President Abraham Lincoln and his Cabinet reportedly observed, through field glasses from an elevated spot in Washington, Jackson's large Confederate flag flying atop the Marshall House inn in Alexandria, across the Potomac River.[1][2] Jackson had reportedly stated the flag would only be taken down "over his dead body".[1][3]

On May 24, 1861, the day after Virginia voters ratified the secession recommendation, federal troops crossed the Potomac and captured Alexandria.[1] One federal regiment was the famously flamboyant 11th New York Zouave Infantry, led by Col. Elmer Ellsworth, who was a close friend of Lincoln.[4]

When approaching the Marshall House, Ellsworth saw the flag, and went inside the building to seize it.[1] When questioned, a boarder at the house informed Ellsworth that he knew nothing about the flag.[5] Ellsworth then climbed the stairs and removed the flag from the flagpole.[1] As Ellsworth returned downstairs with the flag, Jackson suddenly appeared and shot him dead with an English-made double-barrel shotgun.[1][5][6] Then Francis E. Brownell of Ellsworth's regiment shot and bayonetted Jackson, thus killing him.[1][5] Both men immediately became celebrated martyrs for their respective causes.[1][5][7]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1862, an account of his death was published in Richmond, Virginia.[8] In 1863, Union officials established a contraband camp (for former slaves) on or adjacent to or land owned by Jackson's widow in Lewinsville.[9]

In 1999, sociologist and historian James W. Loewen noted in his book Lies Across America that the Sons of Confederate Veterans had placed a bronze plaque on the side of a Holiday Inn that had been constructed on the former site of the Marshall House. Loewen reported that the plaque described Jackson's death but omitted any mention of Ellsworth.[10] Adam Goodheart further discussed the incident and the plaque (which was then within a blind arch near a corner of a Hotel Monaco) in his 2011 book 1861: The Civil War Awakening.[11]

The plaque called Jackson the "first martyr to the cause of Southern Independence" and said he "was killed by federal soldiers while defending his property and personal rights ... in defence of his home and the sacred soil of his native state".[12] In full, it read:

THE MARSHALL HOUSE

stood upon this site, and within the building

on the early morning of May 24,

JAMES W. JACKSON

was killed by federal soldiers while defending his property and

personal rights as stated in the verdict of the coroners jury.

He was

the first martyr to the cause of Southern Independence.

The justice of history does not permit his name to be forgotten.

–––––––––––––––– O –––––––––––––––

Not in the excitement of battle, but coolly and for a great principle,

he laid down his life, an example to all, in defence of his home and

the sacred soil of his native state.

VIRGINIA

In 2013, WTOP reported that some Alexandria residents were advocating the removal of the plaque, but that city officials had no control over the matter as the plaque was on private property.[13] However, in December 2016, Marriott International purchased The Monaco, added it to its boutique Autograph Collection and renamed it as "The Alexandrian".[14] By October 2017, Marriott had removed the plaque from The Alexandrian and had given it to the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.[15][better source needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Snowden, W.H. (1894). Alexandria, Virginia. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company. pp. 5–9. LCCN rc01002851. OCLC 681385571. Retrieved 2019-01-29 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Goodheart, p. 280.

- ^ Leepson, Marc (Fall 2011). Greenberg, Linda (ed.). "The First Union Civil War Martyr: Elmer Ellsworth, Alexandria, and the American Flag" (PDF). The Alexandria Chronicle. Alexandria, Virginia: Alexandria Historical Society, Inc.

- ^ Goodheart, p. 279.

- ^ a b c d (1) "The Murder of Colonel Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (232): 357–358. 1861-06-08. Retrieved 2019-01-28 – via Internet Archive.

(2) "The Murder of Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (233): 369. 1861-06-15. Retrieved 2019-01-28 – via Internet Archive. - ^ "James W. Jackson's shotgun". CivilWar@Smithsonian: First Blood. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution: National Portrait Gallery. 2004. Archived from the original on 2019-01-27. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- ^ (1) Prats, J. J. (ed.). ""Alexandria: Alexandria in the Civil War" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

(2) Fuchs, Tom (2006-02-23). ""Alexandria: Alexandria in the Civil War" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original (photograph) on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

(3) "Wayfinding: Marshall House". City of Alexandria, Virginia. 2018-03-28. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26. - ^ "Life of James W. Jackson, The Alexandria Hero, The Slayer of Ellsworth, Martyr in the Cause of Southern Independence; Containing a Full Account of the Circumstances of His Heroic Death, and the Many Remarkable Incidents In His Remarkable Live, Constituting a True History, More Like Romance Than Reality. Published for the Benefit of His Family". Richmond, Virginia: West & Johnson. 1862. Retrieved 2019-01-27 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Baumgarten, Ronald J. Jr. (2013-09-29). "In Search of the Contraband Camps of McLean, Virginia, Part II: Camp Beckwith". All Not So Quiet Along the Potomac: The Civil War in Northern Virginia & Beyond. Archived from the original (blog) on 2019-01-27. Retrieved 2019-01-27 – via Blogger.

- ^ Loewen, James W. (2000). The Clash of the Martyrs: Virginia: Alexandria. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 294–295. ISBN 9781595586766. LCCN 99014212. OCLC 892054466. Retrieved 2019-01-26 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Goodheart

- ^ (1) Goodheart, p. 292.

(2) Pfingsten, Bill (ed.). ""The Marshall House" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

(3) Groeling, Meg (2017-10-23). "Colonel Elmer Ellsworth and the Marshall House Hotel Plaque". Emerging Civil War: Battlefield Markers & Monuments. Archived from the original (blog) on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-25 – via WordPress. - ^ wtopstaff (2013-02-02). "Curious plaque tells forgotten story". WTOP. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ Barton, Mary Ann (2016-12-14). "Hotel Monaco Sold, to Become The Alexandrian". Patch: Old Town Alexandria. Patch Media. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

As of Dec. 20, a boutique division of Marriott will manage Hotel Monaco and Morrison House in Alexandria, after sale of properties.

- ^ Groeling, Meg (2017-10-23). "Colonel Elmer Ellsworth and the Marshall House Hotel Plaque". Emerging Civil War: Battlefield Markers & Monuments. Archived from the original (blog) on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-25 – via WordPress.

References

[edit]Goodheart, Adam (2012). 1861: The Civil War Awakening. New York: Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc. ISBN 9781400032198. LCCN 2010051326. OCLC 973512612. Retrieved 2019-01-25 – via Google Books.

External links

[edit] Media related to James W. Jackson at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to James W. Jackson at Wikimedia Commons