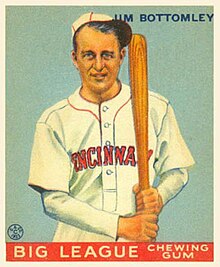

| Jim Bottomley | |

|---|---|

| |

| First baseman / Manager | |

| Born: April 23, 1900 Oglesby, Illinois, U.S. | |

| Died: December 11, 1959 (aged 59) St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Left | |

| MLB debut | |

| August 18, 1922, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 16, 1937, for the St. Louis Browns | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .310 |

| Hits | 2,313 |

| Home runs | 219 |

| Runs batted in | 1,422 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| As player

As manager | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1974 |

| Election method | Veterans Committee |

James Leroy Bottomley (April 23, 1900 – December 11, 1959) was an American professional baseball player, scout and manager. He played in Major League Baseball as a first baseman from 1922 to 1937, most prominently as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals where he helped lead the team to four National League pennants and two World Series titles.

Born in Oglesby, Illinois, Bottomley grew up in Nokomis, Illinois. He dropped out of high school at the age of 16 to raise money for his family. While he was playing semi-professional baseball, the Cardinals scouted and signed Bottomley before the 1920 season. He became an integral member of the Cardinals batting order, driving in 100 or more runs batted in between 1924 and 1929 as the team's cleanup hitter. In 1924, he established a major league record for driving in 12 runs in a nine inning game.[1]

In 1926 he led the National League (NL) in runs batted in and total bases, helping the Cardinals win their first World Series championship. Bottomley was named the NL's Most Valuable Player in 1928 after leading the league in home runs, runs batted in and total bases. He won another World Series with the Cardinals in 1931. Bottomley hit above .300 nine times and had accumulated a .310 career batting average by the end of his sixteen-year major league career. He also played for the Cincinnati Reds and St. Louis Browns and also served as player-manager for the Browns in 1937.

After finishing his playing career with the Browns, Bottomley joined the Chicago Cubs organization as a scout and minor league baseball manager. After suffering a heart attack, Bottomley retired to raise cattle with his wife in Missouri. Bottomley was nicknamed "Sunny Jim" because of his cheerful disposition. Bottomley was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1974 by the Veterans Committee and to the Cardinals Hall of Fame in 2014.

Early life

[edit]Bottomley was born on April 23, 1900,[2] to Elizabeth (née Carter) and John Bottomley in Oglesby, Illinois. His family later moved to Nokomis, Illinois, where Bottomley enrolled in grade school and Nokomis High School.[3] He dropped out when he was 16 years old in order to help support his family financially. Bottomley worked as a coal miner, truck driver, grocery clerk, and railroad clerk. His younger brother, Ralph, died in a mining accident in 1920.[2]

Bottomley also played semi-professional baseball for several local teams to make additional money, earning $5 a game ($101 in current dollar terms).[2][4] A police officer who knew Branch Rickey, the general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, saw Bottomley play, and recommended Bottomley to Rickey.[2]

Professional career

[edit]St. Louis Cardinals

[edit]Rickey dispatched scout Charley Barrett to investigate Bottomley. The Cardinals decided to invite Bottomley to a tryout in late 1919, and signed him to a $150-a-month ($2,636 in current dollar terms) contract.[2] Bottomley began his professional career in minor league baseball in 1920. That year, Bottomley played for the Mitchell Kernels of the Class-D South Dakota League, posting a .312 batting average in 97 games, as Barrett continued to scout him.[5] He also played six games for the Sioux City Packers of the Class-A Western League. During his time in the minor leagues, the media began to call Bottomley "Sunny Jim", due to his pleasant disposition.[2]

The next season, Bottomley played for the Houston Buffaloes of the Class-A Texas League.[2] Bottomley suffered a leg injury early in the season which became infected, and impeded his performance during the season. Bottomley managed only a .227 batting average in 130 games and struggled with his fielding. Unable to sell Bottomley after the season to Houston for $1,200 ($20,499 in current dollar terms), Rickey sold Bottomley to the Syracuse Chiefs of the Class-AA International League for $1,000 ($17,082 in current dollar terms).[6] Fully recovered from his leg injury in 1922, Bottomley batted .348 with 14 home runs, 15 triples, and a .567 slugging percentage for the Chiefs. After the season, the Cardinals purchased Bottomley from the Chiefs for $15,000 ($273,042 in current dollar terms).[2]

Bottomley made his Major League Baseball debut for the St. Louis Cardinals on August 18, 1922. Replacing Jack Fournier, Bottomley batted .325 in 37 games. The Cardinals named Bottomley their starting first baseman in 1923. As a rookie, Bottomley batted .371, finishing second in the National League (NL) behind teammate Rogers Hornsby, who batted .384. His .425 on-base percentage also finished second in the NL behind Hornsby, while he finished sixth in slugging percentage, with a .535 mark. His 94 runs batted in (RBIs) were tenth-best in the league.[7]

Bottomley posted a .316 batting average in 1924.[2] In a game against the Brooklyn Dodgers on September 16, 1924, Bottomley set the major league record for RBIs in a single game, with 12, breaking Wilbert Robinson's record of 11, set in 1892. Robinson was serving as the manager of the Dodgers at the time.[2][8] (Bottomley had two home runs, a double and three singles as he went 6-for-6 at the plate.) This mark has since been tied by Mark Whiten in 1993.[9] As he finished the season with 111 RBIs, placing third in the NL, Bottomley's 14 home runs were seventh-best in the NL, while his .500 slugging percentage was good for tenth.[10] On August 29, Bottomley became the last left-handed player to record an assist while playing second base.[11]

Bottomley hit .367 in 1925, finishing second in the NL to Hornsby. He led the NL with 227 hits, while his 128 RBIs were third-best, and his .413 on-base percentage was seventh-best in the league.[12] Bottomley batted .298 during the 1926 season, with an NL-leading 120 RBIs. His 19 home runs placed second in the NL, behind Hack Wilson's 21, while his .506 slugging percentage was sixth-best.[13] He batted .345 in the 1926 World Series, as the Cardinals defeated the New York Yankees.[2]

In 1927, Bottomley finished the season with 124 RBIs, fourth best in the league, and a .509 slugging percentage, finishing sixth in the NL.[14] Bottomley hit .325 with 31 home runs and 136 RBIs in 1928, leading the league in home runs and RBIs.[15] He also became the second Major League player in history to join the 20–20–20 club, and became the first (since achieved by Jimmy Rollins in 2007) to record a 30 double, 20 triple, 30 home run season.[16] That year, he won the League Award, given to the most valuable player of the NL.[17] The Cardinals reached the 1928 World Series, and Bottomley batted .214 as they lost to the New York Yankees.[18]

In 1929, Bottomley hit 29 home runs, finishing seventh in the NL, while his 137 RBIs were fifth-best, and his .568 slugging percentage placed him in eighth.[19] After having what manager Gabby Street considered a "poor year" in 1930,[20] Bottomley struggled in the 1930 World Series, batting .045 in 22 at-bats, as the Cardinals lost to the Philadelphia Athletics. Following the series, Bottomley described his World Series performance as "a bust as far as hitting goes".[21][22][23]

Amid questions about Bottomley's status with the Cardinals heading into the 1931 season, he demonstrated renewed hitting ability during spring training.[24] Despite the presence of Ripper Collins, a superior fielder who transferred to the Cardinals from the Rochester Red Wings of the International League, Street announced that Bottomley would remain the starting first baseman.[25] However, Bottomley suffered an injury and struggled early in the 1931 season after returning to the game, and it appeared that he might lose his job to Collins, who filled in for Bottomley during his injury.[26] Bottomley returned to form after his return, and he finished the season with a .3482 batting average, placing third behind teammate Chick Hafey's .3489 and Bill Terry's .3486, the closest batting average finish in MLB history.[2] His .534 slugging percentage was the sixth best in the league.[27] The Cardinals reached the 1931 World Series, with Bottomley batting .160, as the Cardinals defeated the Athletics.[28] That offseason, other teams began to attempt to trade for either Bottomley or Collins.[29] Bottomley batted .296 in 1932, though he played in only 91 games.[2]

Cincinnati Reds

[edit]After the 1932 season, the Cardinals traded Bottomley to the Cincinnati Reds for Ownie Carroll and Estel Crabtree, in an attempt to partner Bottomley with Chick Hafey in developing a more potent offensive attack. Bottomley had also sought Cincinnati's managerial position that offseason, which instead went to Donie Bush.[30][31]

Bottomley threatened to quit baseball in a salary dispute with the Reds, as he attempted to negotiate a raise from his $8,000 salary ($188,298 in current dollar terms), a reduction from the $13,000 salary ($290,312 in current dollar terms) he earned with the Cardinals the previous year.[32] He and the Reds eventually came to terms on a one-year contract believed to be worth between $10,000 and $13,000.[33] Bottomley finished eighth in the NL with 83 RBIs in 1933, and ninth with 13 home runs.[34] In three seasons with the Reds, Bottomley failed to hit higher than .283 or record more than 83 RBIs in a season. Bottomley left the Reds during spring training in 1935 due to a salary dispute,[35] deciding to return to the team in April.[36]

St. Louis Browns

[edit]Before the 1936 season, the Reds traded Bottomley to the St. Louis Browns of the American League (AL), who were managed by Hornsby, for Johnny Burnett.[37] During a July road trip, Bottomley announced his retirement as a result of an injured back;[38][39] however, he changed his mind and decided to remain with the team.[40] Bottomley batted .298 for the 1936 season.[2]

Bottomley decided to return to baseball in 1937.[41] When the Browns struggled during the 1937 season, beginning the season with a 25–52 win–loss record, the Browns fired Hornsby and named Bottomley their player-manager.[2][42] Bottomley led the Browns to 21 more victories, as the team finished the season in eighth place, with a 46–108 record. The Browns trailed the seventh place Athletics by 9+1⁄2 games, and were 56 games out of first place. As a player, Bottomley batted .239 in 65 games during the 1937 season.[2] Bottomley was among the ten oldest players in the AL that year.[43]

The Browns did not retain Bottomley after the 1937 season,[44] replacing him with Street, who served as his first assistant during the 1937 season.[45] In 1938, Bottomley served as the player-manager of Syracuse. After a bad start to the season, and with team president Jack Corbett not adding capable players, Bottomley resigned and was replaced with Dick Porter.[46] Bottomley also indicated that he did not want to continue playing.[47]

Career statistics

[edit]In 1,991 games over 16 seasons, Bottomley posted a .310 batting average (2,313-for-7,471) with 1,177 runs, 465 doubles, 151 triples, 219 home runs, 1,422 RBI, 58 stolen bases, 664 bases on balls, .369 on-base percentage and .500 slugging percentage. Defensively, he recorded a .988 fielding percentage as a first baseman. In 24 World Series games over four Series, he batted just .200 (18-for-90) with one home run and 10 RBI.[48]

Managerial record

[edit]| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| SLB | 1937 | 77 | 21 | 56 | .273 | 8th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 77 | 21 | 56 | .273 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

Personal life

[edit]Bottomley married Elizabeth "Betty" Browner, who operated a St. Louis beauty parlor, on February 4, 1933.[49] The couple had no children.[2] After he retired from baseball in 1938, Bottomley and his wife moved to the Bourbon, Missouri, area, where he raised Hereford cattle.[2] In 1939, Bottomley became a radio broadcaster, signing a deal with KWK, an AM broadcasting station, to broadcast Cardinals and Browns games.[50][51]

Bottomley returned to baseball as a scout for the Cardinals in 1955.[52] In 1957, he joined the Chicago Cubs as a scout[53] and managed the Pulaski Cubs of the Class D Appalachian League. While managing in Pulaski, Bottomley suffered a heart attack. The Bottomleys moved to nearby Sullivan, Missouri.[2] Bottomley died of a heart ailment in December 1959.[54] He and his wife Betty were interred in the International Order of Odd Fellows Cemetery, Sullivan, Missouri.[2]

Honors

[edit]Bottomley holds the single-season record for most unassisted double plays by a first baseman, with eight. Bottomley is also known as the only man to be sued for hitting a home run ball that hit a fan. The plaintiff was not looking. He had over 100 RBIs in each season from 1924 to 1929. Bottomley was the second player in baseball history to hit 20 or more doubles, triples, and home runs in one season (Frank Schulte being the first)[55] and the first of two players (Lou Gehrig being the other) to collect 150 or more doubles, triples, and home runs in a career.[56]

Bottomley was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame posthumously in 1974 by the Veterans Committee. The Baseball Writers' Association of America charged that the Veterans Committee was not selective enough in choosing members.[57] Charges of cronyism were levied against the Veterans Committee.[58] When Bottomley was elected, the Veterans Committee included Frankie Frisch, a teammate of Bottomley's with the Cardinals. Frisch and Bill Terry, also a member of the Veterans Committee at the time, shepherded the selections of teammates Jesse Haines in 1970, Dave Bancroft and Chick Hafey in 1971, Ross Youngs in 1972, George Kelly in 1973, and Freddie Lindstrom in 1976.[59] This led to the Veterans Committee having its powers reduced in subsequent years.[60]

In 2014, the Cardinals announced Bottomley was among 22 former players and personnel to be inducted into the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame Museum for its inaugural class of 2014.[61]

The city park in his adopted home town of Sullivan, Missouri is named for Bottomley.[2] Also the park in his birthplace Oglesby, Illinois. A museum in Nokomis, Illinois, the Bottomley-Ruffing-Schalk Baseball Museum, is dedicated to Bottomley and fellow Hall of Famers Ray Schalk and Red Ruffing, who were also Nokomis residents.[2][62]

See also

[edit]- 20–20–20 club

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball annual doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball runs batted in records

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of St. Louis Cardinals team records

- St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame Museum

- List of Major League Baseball single-game hits leaders

References

[edit]- ^ http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1924/B09160BRO1924.htm The record has been equaled only once; by Mark Whiten 0/7/93 retrieved August 30, 2015

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Johnson, Bill. "Jim Bottomley". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Bases loaded: Nokomis second to none in baseball history

- ^ "End For A Blithe Spirit: Sunny Jim Bottomley Dies Suddenly; Combined Color And Top-Flight Talent". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. December 12, 1959. p. 14. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "Puzzlers In Baseball: Scout Recalls a Story of Jim Bottomley". The News and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina. March 22, 1929. p. 8. Retrieved May 14, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Talk To Students Gives Rickey Star First Sacker: Jim Bottomley, Discarded as Failure, Stages Meteoric Comeback to Fame". Ludington Daily News. Associated Press. November 21, 1923. p. 6. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "1923 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "Robinson Looks On As Jim Bottomley Breaks His Record". Hartford Courant. September 17, 1924. p. 17. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ Fimrite, Ron (September 20, 1993). "Mark Whiten". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 2, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "1924 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Preston, JG (September 6, 2009). "Left-handed throwing second basemen, shortstops and third basemen". prestonjg.wordpress.com. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "1925 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "1926 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "1927 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "1928 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Martell, Matt (December 27, 2022). "Jimmy Rollins Has a Long Way to Go Before He Gets His Hall of Fame Due". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Bell, Brian (December 5, 1928). "Jim Bottomley Voted Most Valuable In National League: St. Louis Player Awarded Coveted Baseball Honors; "Sunny Jim" Leads Freddy Lindstrom of Giants by Six Points; Eight Baseball Writers Select Infielder". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. pp. 2–3. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "1928 World Series – New York Yankees over St. Louis Cardinals (4–0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "1929 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Street, Gabby (February 17, 1931). "Street, Summing Up Cards' Chances, Believes Bottomley Due For Great Year". Kentucky New Era. p. 4. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "'Sunny Jim' Bottomley Has Unwelcome Record". Hartford Courant. November 16, 1930. p. 7C. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ Bottomley, Jim (October 9, 1930). "Jim Bottomley Admits He Was Bust In Series: Has No Excuses To Offer for Batting Slump". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Universal Service. p. 18. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "1930 World Series – Philadelphia Athletics over St. Louis Cardinals (4–2)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Regains Old Hitting Form: Veteran to Hold Down First Base For Cards Again". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. March 23, 1931. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Davis, Ralph (March 27, 1931). "'Sunny Jim' Bottomley Will Remain With Cards As First Baseman". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 47. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Regains Batting Eye on Eastern Trip: Cardinal Star Lands Fourth Place With .338; Davis Continues to Lead National Loop Race With Average of .350". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. August 29, 1931. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "1931 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "1931 World Series – St. Louis Cardinals over Philadelphia Athletics (4–3)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "Carey Seeking Jim Bottomley: With Bissonette Injured, Robins Need First-Sacker". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. March 25, 1932. p. 39. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley May Be Named Manager Of Reds". Hartford Courant. September 25, 1932. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Is Traded To Redlegs by St. Louis: Cincinnati Obtains Cardinal First Sacker in Swap for Owen Carroll and Estil Crabtree". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. December 18, 1932. p. 1-B. Retrieved May 22, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Threatens To Quit". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. January 31, 1933. p. 28. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Signs One-year Contract With Cincinnati: Yields After 4-Hour Talk With Weil". Rochester Evening Journal. March 3, 1933. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "1933 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Quits the Reds". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. March 30, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved May 22, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Will Return to Redlegs". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. April 9, 1935. p. 31. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ "To Join Browns". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. March 22, 1936. p. 15. Retrieved May 23, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Sunny Jim Bottomley Announces His Retirement From Baseball". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. July 18, 1936. p. 6. Retrieved June 4, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Checks Out: Jim Bottomley Given Big Cheer Last Time Up". San Jose News. Associated Press. July 17, 1936. p. 6. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley to Hold Post". Los Angeles Times. July 22, 1936. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Changes Mind About Retiring From Game". Los Angeles Times. January 3, 1937. p. A11. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ "Hornsby Is Given Air By Barnes: Jim Bottomley Named Acting Manager of Brownies". San Jose News. Associated Press. July 21, 1937. p. 6. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ "1937 American League Awards, All-Stars, & More Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Given Release: Popular St. Louis Diamond Performer Loses Job as Browns' Pilot". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. November 20, 1937. p. 16. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ "Gabby Street and Jim Bottomley Part Company". The Milwaukee Journal. November 28, 1937. p. 17. Retrieved May 23, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Quits Syracuse Manager Post". Schenectady Gazette. United Press International. May 20, 1938. p. 30. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Resigns As Chiefs' Manager". Meriden Record. Associated Press. May 20, 1938. p. 4. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley statistics and history". Baseball Reference.com. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ ""Sunny Jim" Bottomley Signs Marriage Contract". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. February 5, 1933. p. 2. Retrieved May 21, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Gets Job on Radio". Los Angeles Times. April 29, 1939. p. 11. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Gets Job As Baseball Announcer". Meriden Record. Associated Press. April 29, 1939. p. 4. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ "'Sunny Jim' Bottomley To Scout for Cardinals". Hartford Courant. April 21, 1955. p. 16A. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ "Bottomley Joins Chicubs As Scout". The Gadsden Times. Associated Press. January 27, 1957. p. 10. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Bottomley Dies: Heart Ailment Fatal to Former First Baseman". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. December 11, 1959. p. 14. Retrieved May 14, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Granderson joins elite homer-double-triple club, helping Tigers beat Seattle". USA Today. September 7, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "How Jim Bottomley smiled his way to the Hall of Fame". KSDK. August 17, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "Baseball Brouhaha Brewing". The Evening Independent. January 19, 1977. p. 1C. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Sullivan, Tim (December 21, 2002). "Hall voter finds new parameters unhittable". The San Diego Union Tribune. p. D.1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Jaffe, Jay (July 28, 2010). "Prospectus Hit and Run: Don't Call it the Veterans' Committee". Baseball Prospectus. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Booth, Clark (August 12, 2010). "The good news: Baseball Hall looking at electoral revamp". Dorchester Reporter. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Cardinals Press Release (January 18, 2014). "Cardinals establish Hall of Fame & detail induction process". www.stlouis.cardinals.mlb.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Kane, Dave (October 8, 2009). "Town's baseball ties on display at museum". The Register-Mail. Galesburg, Illinois. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Johnson, Bill. "Jim Bottomley". SABR.

- Obituary at The Deadball Era via Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Jim Bottomley at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Jim Bottomley managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Jim Bottomley at Find a Grave