John Dickson Carr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 30, 1906 Uniontown, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | February 28, 1977 (aged 70) Greenville, South Carolina, United States |

| Resting place | Springwood Cemetery, Greenville |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Genre | Detective novel, murder mystery |

| Literary movement | Golden Age of Detective Fiction |

| Notable works | The Hollow Man, The Burning Court |

| Relatives | Shelly Dickson Carr (granddaughter- Mystery Author) |

John Dickson Carr (November 30, 1906 – February 27, 1977) was an American author of detective stories, who also published using the pseudonyms Carter Dickson, Carr Dickson, and Roger Fairbairn.

He lived in England for a number of years, and is often grouped among "British-style" mystery writers. Most (though not all) of his novels had English settings, especially country villages and estates, and English characters. His two best-known fictional detectives (Dr. Gideon Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale) were both English.

Carr is generally regarded as one of the greatest writers of so-called "Golden Age" mysteries; complex, plot-driven stories in which the puzzle is paramount. He was influenced in this regard by the works of Gaston Leroux and by the Father Brown stories of G. K. Chesterton. He was a master of the so-called locked room mystery, in which a detective solves apparently impossible crimes. The Dr. Fell mystery The Hollow Man (1935), usually considered Carr's masterpiece, was selected in 1981 as the best locked-room mystery of all time by a panel of 17 mystery authors and reviewers.[1] He also wrote a number of historical mysteries.

The son of Wooda Nicholas Carr, a U.S. congressman from Pennsylvania, Carr graduated from The Hill School in Pottstown in 1925 and Haverford College in 1929. During the early 1930s, he moved to England, where he married Clarice Cleaves, an Englishwoman. He began his mystery-writing career there, returning to the United States as an internationally known author in 1948.

In 1950, his biography of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle earned Carr the first of his two Special Edgar Awards from the Mystery Writers of America; the second was awarded in 1970, in recognition of his 40-year career as a mystery writer. He was also presented the MWA's Grand Master award in 1963. Carr was one of only two Americans ever admitted to the British Detection Club.

In early spring 1963, while living in Mamaroneck, New York, Carr suffered a stroke, which paralyzed his left side. He continued to write using one hand, and for several years contributed a regular column of mystery and detective book reviews, "The Jury Box", to Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. Carr eventually relocated to Greenville, South Carolina, and died there of lung cancer on February 28, 1977.[2]

Dr. Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale

[edit]"Mr. Carr can lead us away from the small, artificial, brightly-lit stage of the ordinary detective plot into the menace of outer darkness. He can create atmosphere with an adjective, alarm with an allusion, or delight with a rollicking absurdity. In short he can write" -

Carr's two major detective characters, Dr. Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale, are superficially quite similar. Both are large, upper-class, eccentric Englishmen somewhere between middle-aged and elderly. Dr. Fell, who is fat and walks only with the aid of two canes, was clearly modeled on the British writer G. K. Chesterton and is at all times civil and genial. He has a great mass of untidy hair that is often covered by a "shovel hat" and he generally wears a cape. He lives in a modest cottage and does not have any official association with public authorities.

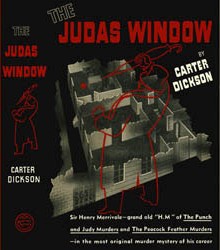

Henry Merrivale or "H.M.", on the other hand, although stout and with a majestic "corporation", is active physically and is feared for his ill-temper and noisy rages. In a 1949 novel, A Graveyard To Let, for example, he demonstrates an unexpected talent for hitting baseballs improbable distances. A wealthy descendant of the "oldest baronetcy" in England, he is part of the Establishment (even though he frequently rails against it) and in the earlier novels is the director of the British Secret Service. In The Plague Court Murders he is said to be qualified as both a barrister and a medical doctor. Even in the earliest books the bald, bespectacled, and scowling H.M. is clearly a Churchillian figure and in the later novels this similarity is somewhat more consciously evoked. Many of the Merrivale novels, written using the Carter Dickson byline, rank with Carr's best work, including the much-praised The Judas Window (1938).

Many of the Fell novels feature two or more different impossible crimes, including He Who Whispers (1946) and The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941). The novel The Crooked Hinge (1938) combines a seemingly impossible throat-slashing, witchcraft, a survivor of the ship Titanic, an eerie automaton modeled on Wolfgang von Kempelen's chess player, and a case similar to that of the Tichborne Claimant into what is often cited as one of the greatest classics of detective fiction. But even Carr's biographer, Douglas G. Greene,[3] notes that the explanation, like many of Carr's in other books, seriously stretches plausibility and the reader's credulity.

Dr. Fell's own discourse on locked room mysteries in chapter 17 of The Hollow Man is acclaimed critically and is sometimes printed as a stand-alone essay in its own right.

Other works

[edit]Besides Dr. Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale, Carr mysteries feature two other series detectives: Henri Bencolin and Colonel March.

A few of his novels do not feature a series detective. The most famous of these, The Burning Court (1937), involves witchcraft, poisoning, and a body that disappears from a sealed crypt in suburban Philadelphia; it was the basis for the French movie La chambre ardente (1962).

Carr wrote in the short story format as well. Julian Symons, in Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel: A History (1972), said: "Most of Carr's stories are compressed versions of his locked-room novels, and at times they benefit from the compression. Probably the best of them are in the Carter Dickson book, The Department of Queer Complaints (1940), although this does not include the brilliantly clever H.M. story The House in Goblin Wood or a successful pastiche which introduces Edgar Allan Poe as a detective."[4]

During 1950, Carr wrote the novel, The Bride of Newgate, set during 1815 at the close of the Napoleonic Wars, "one of the earliest historical mystery novels."[5] The Devil in Velvet and Fire, Burn! are the two historical novels (involving also Time travel) with which he said he himself was most pleased. With Adrian Conan Doyle, the youngest son of Arthur Conan Doyle, Carr wrote Sherlock Holmes stories that were published in the 1954 collection The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes. He was also honored by the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by being asked to write the biography for the legendary author. The book, The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, was published during 1949 and received generally favorable reviews for its vigor and entertaining style.

Critical appraisal

[edit]Dr. Fell has generally been considered to be Carr's major creation. The British novelist Kingsley Amis, for instance, writes in his essay, "My Favorite Sleuths", that Dr. Fell is one of the three great successors to Sherlock Holmes (the other two are Father Brown and Nero Wolfe) and that H.M., "according to me is an old bore." This may be in part because in the Merrivale novels written after World War II, H.M. frequently became a comic caricature of himself, especially in the physical misadventures in which he found himself at least once in every novel. Humorous as these episodes were intended to be, they also tended to have the effect of decreasing the mystique of the character. Earlier, however, H.M. had been regarded more favorably by a number of critics. Howard Haycraft, author of the seminal Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story, wrote during 1941 that H.M. or "The Old Man" was "the present writer's admitted favorite among contemporary fictional sleuths". During 1938 the British mystery writer R. Philmore wrote in an article called "Inquest on Detective Stories" that Sir Henry was "the most amusing of detectives". And further: "Of course, H.M. is so much the best detective that, once having invented him, his creator could get away with any plot."

There is a book-length critical study by S. T. Joshi, John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study (1990) (ISBN 0-87972-477-3) and a chapter on Carr in Joshi's book Varieties of Crime Fiction (2019) ISBN 978-1-4794-4546-2.

The definitive biography of Carr is by Douglas G. Greene, John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles (1995) (ISBN 1-883402-47-6). From an obituary published in Greenville, South Carolina, Carr allegedly also published using the name of Fenton Carter, but no works by anyone of this name have yet been identified.

Radio plays

[edit]Carr also wrote many radio scripts, particularly for the Suspense radio anthology series in America and for its UK equivalent Appointment With Fear introduced by Valentine Dyall, as well as many other dramas for the BBC, and some screenplays. His 1943 half-hour radio play Cabin B-13 was expanded into a series on CBS during 1948–49[6] for which Carr wrote all 23 scripts, basing some on earlier works or re-presenting devices that Chesterton had used. The 1943 play Cabin B-13 was also expanded into the script for the 1953 movie Dangerous Crossing, directed by Joseph M. Newman and featuring Michael Rennie and Jeanne Crain. Carr worked extensively for BBC Radio during World War II, writing both mystery stories and propaganda scripts. During the late 1940s he hosted Murder by Experts transmitted by Mutual radio. He introduced works by other mystery writers who were the week's guest writers. The show originated from Mutual's main station WOR in New York City. Many of these shows are available for free listening or downloading at the Internet Archive.

Film and television

[edit]Carr's works were the basis for several movies, including The Man With a Cloak (1951) and Dangerous Crossing (1953). The Emperor's Snuffbox was filmed as That Woman Opposite (1957), and La Chambre Ardente (1962) was a loose adaptation of The Burning Court.

Various Carr stories formed the basis for episodes of television series, particularly those without recurring characters such as General Motors Presents. During 1956, the television series Colonel March of Scotland Yard, featuring Boris Karloff as Colonel March, was based on Carr's character and his stories and was broadcast for 26 episodes.

Publications

[edit]As John Dickson Carr

[edit]Henri Bencolin mysteries

[edit]- It Walks By Night – 1930

- The Lost Gallows – 1931

- Castle Skull – 1931

- The Waxworks Murder – 1932 (US title: The Corpse In The Waxworks)

- The Four False Weapons, Being the Return of Bencolin – 1937

Dr. Gideon Fell mysteries

[edit]- Hag's Nook – 1933

- The Mad Hatter Mystery – 1933

- The Eight of Swords – 1934

- The Blind Barber – 1934

- Death-Watch – 1935

- The Hollow Man – 1935 (US title: The Three Coffins)

- The Arabian Nights Murder – 1936

- To Wake the Dead – 1938

- The Crooked Hinge – 1938

- The Black Spectacles – 1939 (US title: The Problem Of The Green Capsule)

- The Problem of the Wire Cage – 1939

- The Man Who Could Not Shudder – 1940

- The Case of the Constant Suicides – 1941

- Death Turns the Tables – 1941 (UK title: The Seat of the Scornful, 1942)

- Till Death Do Us Part – 1944

- He Who Whispers – 1946

- The Sleeping Sphinx – 1947

- Below Suspicion – 1949 (with Patrick Butler)

- The Dead Man's Knock – 1958

- In Spite of Thunder – 1960

- The House at Satan's Elbow – 1965

- Panic in Box C – 1966

- Dark of the Moon – 1967

Non-series mysteries

[edit]- Poison in Jest – 1932 (features Jeff Marle from the Henri Bencolin series)

- The Burning Court – 1937

- The Emperor's Snuff-Box – 1942

- The Nine Wrong Answers – 1952

- Patrick Butler for the Defence – 1956 (features Patrick Butler from the Dr. Fell novel Below Suspicion)

Historical mysteries

[edit]- The Bride of Newgate – 1950

- The Devil in Velvet – 1951

- Captain Cut-Throat – 1955

- Fire, Burn! – 1957

- Scandal at High Chimneys: A Victorian Melodrama – 1959

- The Witch of the Low Tide: An Edwardian Melodrama – 1961

- The Demoniacs – 1962

- Most Secret (novel) – 1964 (This was a revision of a novel by Carr that was published in 1934 as Devil Kinsmere under the pseudonym "Roger Fairbairn")

- Papa La-Bas – 1968

- The Ghost's High Noon – 1970

- Deadly Hall – 1971

- The Hungry Goblin: A Victorian Detective Novel – 1972 (Wilkie Collins is the detective)

Short story collections

[edit]- The Department of Queer Complaints, as Carter Dickson - 1940

- Dr. Fell, Detective, and Other Stories - 1947

- The Third Bullet and Other Stories of Detection - 1954

- The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes, with Adrian Conan Doyle - 1954 (Sherlock Holmes)

- The Men Who Explained Miracles - 1963

- The Door to Doom and Other Detections - 1980 (includes radio plays)

- The Dead Sleep Lightly - 1983 (radio plays)

- Fell and Foul Play - 1991 (includes the full version of The Third Bullet and the short story 'Harem-Scarem', not in any other collection)

- The Kindling Spark: Early Tales of Mystery, Horror, and Adventure --2022. Apprentice stories edited by Dan Napolitano. Crippen & Landru

Stage plays

[edit]- Speak of the Devil - Crippen & Landru, 1994 (a radio play in 8 parts). First publication of Carr's radio script. Written in 1941.

- 13 to the Gallows - Crippen & Landru, 2008. A collection of 4 stage plays, written during the early 1940s —- 2 by Carr alone, and 2 in collaboration with the BBC's Val Gielgud.

Radio plays

[edit]- The Island of Coffins - Crippen & Landru, 2020. A collection of radio scripts from the Cabin B-13 radio show, written during 1948-1949.

- The Old Time Radio Series "Suspense" contains 22 plays by Carr, many of them not available in printed form. The radio plays can be downloaded from this site in MP3 format: https://archive.org/index.php]

- BBC has issued a set of two 90-minute cassettes containing radio versions of The Hollow Man and Till Death us Do Part featuring Donald Sinden as Dr. Fell (also now on CD).

Non-fiction

[edit]- Brotherhood of Shadows - 1923. Unpublished essay

- The Murder of Sir Edmund Godfrey - 1936, historical analysis of a noted murder of 1678

- The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle - 1949, the authorized biography

As Carter Dickson

[edit]Sir Henry Merrivale mysteries

[edit]- The Plague Court Murders - 1934

- The White Priory Murders- 1934

- The Red Widow Murders - 1935

- The Unicorn Murders - 1935

- The Punch and Judy Murders -1936 (UK title: The Magic Lantern Murders)

- The Ten Teacups - 1937 (US title: The Peacock Feather Murders)

- The Judas Window - 1938 (alternate US paperback title: The Crossbow Murder)

- Death in Five Boxes - 1938

- The Reader is Warned - 1939

- And So To Murder - 1940

- Murder in The Submarine Zone - 1940 (US title: Nine - And Death Makes Ten, also published as Murder in the Atlantic)

- Seeing is Believing - 1941 (alternate UK paperback title: Cross of Murder)

- The Gilded Man - 1942 (alternate US paperback title: Death and The Gilded Man)

- She Died A Lady - 1943

- He Wouldn't Kill Patience - 1944

- The Curse of the Bronze Lamp - 1945 (UK title: Lord of the Sorcerers, 1946)

- My Late Wives - 1946

- The Skeleton in the Clock - 1948

- A Graveyard To Let - 1949

- Night at the Mocking Widow - 1950

- Behind the Crimson Blind - 1952

- The Cavalier's Cup - 1953

Colonel March mysteries

[edit]- The Department of Queer Complaints (as Carter Dickson) (detective: Colonel March) - 1940 (The 1940 volume contains 7 stories about Colonel March and 4 non-series stories. The 7 March stories were reprinted as Scotland Yard: Department of Queer Complaints, Dell mapback edition, 1944.)

- Merrivale, March and Murder - 1991 'The Department of Queer (ODD) Complaints' It contains all of the Colonel March short stories, and the short story 'The Diamond Pentacle', not in any other collection)

In the early 1950s Boris Karloff played Col. March in a weekly television series Colonel March of Scotland Yard.

Non-series mysteries

[edit]

- The Bowstring Murders - 1933 (Originally published as by Carr Dickson, but Carr's publishers complained that the name was too similar to Carr's real name, so Carter Dickson was substituted.)

- The Third Bullet (John Dickson Carr) - 1937 (novella)

- Drop to His Death (in collaboration with John Rhode) - 1939 (US title: Fatal Descent)

Historical mysteries

[edit]- Fear Is the Same - 1956

Biography

[edit]- John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles by Douglas G. Greene, Otto Penzler Books/ Simon & Schuster, 1995. Biography & critical study of his works.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pugmire, John. "A Locked Room Library". Mystery File. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "Forgotten authors No.50: John Dickson Carr". The Independent. 21 March 2010.

- ^ Douglas G. Greene (1995), John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles, Otto Penzler, ISBN 9781883402471

- ^ Julian Symons, Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel: A History, first published Faber and Faber 1972, with revisions Penguin 1974, ISBN 0-14-003794-2

- ^ Donsbach, Margaret. "The Bride of Newgate by John Dickson Carr". HistoricalNovels.info. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved 2019-10-04.

External links

[edit]- John Dickson Carr at Library of Congress, with 120 library catalog records

- Carter Dickson at LC Authorities, with 40 records, and at WorldCat

- John Dickson Carr at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Illustrated Bibliography of 1st Editions

- The John Dickson Carr Collector – pictures of first edition covers (archived 2018)

- John Dickson Carr: Explaining the Inexplicable by Douglas G. Greene, undated at MysteryNet.com (archived 2018)

- Petri Liukkonen. "John Dickson Carr". Books and Writers.

- John Dickson Carr – Master of the Locked Room Mystery by Alexander G. Rubio, 30 November 2006 at BitsofNews.com (archived 2013)

- John Dickson Carr One Hundred Years On by Nicholas Fuller, Spring 2007 at Mystericale.com

Book review sites/annotated book lists

[edit]- The Ministry of Miracles: The Detective Fiction of John Dickson Carr a site made by Nicholas Fuller which includes book reviews.

- The Grandest Game in the World a blog by Nicholas Lester Fuller which includes book reviews and expands upon the old site above.

- Grobius Shortling's John Dickson Carr (Carter Dickson) Page a site made by Grobius Shortling which includes ratings & book reviews.

Forums

[edit]- John Dickson Carr - Golden Age Mysteries a discussion forum for fans.