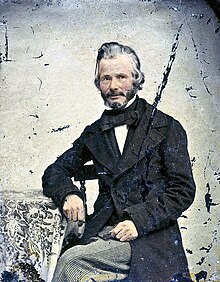

John Stringfellow | |

|---|---|

19th century tin-plate photograph | |

| Born | 1799 |

| Died | 13 December 1883 (aged 84) Chard, Somerset, England |

| Known for | Aerial Steam Carriage |

| Spouse |

Hannah Ketch (m. 1827) |

| Children | 4 daughters, 6 sons |

John Stringfellow (1799 – 13 December 1883) was a British early aeronautical inventor, known for his work on the aerial steam carriage[1] with William Samuel Henson.

Life

[edit]

Stringfellow was born in Attercliffe, England to Martha [née Gillan] and William Stringfellow, stone mason. Initially apprenticed to the lace making trade in Nottingham, c.1820 he relocated to Chard, Somerset to work as an engineer of bobbins and carriages for the lace industry, becoming so successful that he started his own company. On 27 February 1827 he married Hannah Keetch.[2] They had 10 children, including a son who died in infancy and a daughter, Laura, who had epilepsy and died age 29.[3]

Together with William Samuel Henson, he had ambitions of creating an international company, the Aerial Transit Company, with designs showing aeroplane travel to exotic locations like Egypt and China.[4] The initial designs were flawed, with Stringfellow's ideas centred on monoplane and triplane models and Henson's ideas centred on an underpowered steam-powered vehicle, however In 1848 Stringfellow achieved the first ever powered flight using an unmanned 10 ft wingspan steam-powered monoplane, built in a disused lace factory in Chard, Somerset.[5] Employing two contra-rotating propellers on the first attempt, made indoors, the machine flew ten feet before becoming destabilised, damaging the craft. The second attempt was more successful, the machine leaving a guide wire to fly freely, achieving some thirty yards of straight and level powered flight.[6][7][8] A bronze model of that first primitive aircraft stands in Fore Street in Chard. The town's museum has a unique exhibition of flight before the advent of the internal combustion engine and before the manned, powered flight made famous by the Wright Brothers. Stringfellow also invented and patented compact electric batteries, which were used in early medical treatment. Stringfellow's work was featured in an exhibition in 1868 at The Crystal Palace in London.

Stringfellow was also a member of the South West Photographic Society and gave lectures about his inventions with photographs as illustration and proof of his pioneering aviation work. A keen photographer in his spare time, Stringfellow had begun learning the new art / science in the late 1850s, being among the first to produce a wet print of an image and quickly becoming proficient enough to advertise as a professional portrait photographer at his studio near the family home in Chard High Street. The studios in Chard and in Crewkerne are where some of his flying vehicle machines were photographed. The 1871 census of England and Wales lists his occupation as "Machinist & Photographer".[9]

It is recorded that Stringfellow met Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Marconi at regular South West Engineering Institution and Royal Society events, enjoying great debates over the science and engineering principles of the day with his fellow engineers. In 1868 he was elected a member of the Royal Aeronautical Society and used his prize money to build a larger workspace for continuing his experiments. However, at nearly 70 years, his sight was beginning to fail and he was unable to make further progress.[3] His 1881 census status is "Retired Mechanician Inventor of Flying Machines".[10]

John Stringfellow died in 1883 at the age of 84 and was buried in Chard Cemetery, Somerset, where there is a commemorative family monument.[11][12][13]

Stringfellow's first powered flight achievement was referenced in the 1965 film The Flight of the Phoenix. The character Heinrich Dorfmann (Hardy Krüger), a German aeroplane designer, explains that it was a model aeroplane that made the first powered flight in 1851 and though his own experience with aeroplane design is with building models, the principles are the same. His design for an aeroplane to be built from the scraps of their crashed plane will fly them out of the desert to safety.

Stringfellow and Henson are honoured by the Royal Aeronautical Society with an annual lecture and dinner in Yeovil[14][circular reference]

See also

[edit]- Aviation history

- Frederick Brearey

- George Cayley, aviation pioneer

- John Chapman, engineer

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Royal Aeronautical Society | Heritage | WS Henson's 'Aerial Steam Carriage': Specification (1842-1843)". aerosocietyheritage.com.

- ^ "Hannah Stringfellow, née Keetch (1807–1888), Wife of the Pioneer Aeronaut | Art UK".

- ^ a b "John Stringfellow". Graces Guide.

- ^ "John Stringfellow".

- ^ "Geograph:: Stringfellow Gallery, Chard © Derek Harper".

- ^ "FLYING MACHINES - John Stringfellow".

- ^ Parramore, Thomas C. (1 March 2003). First to Fly: North Carolina and the Beginnings of Aviation. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9780807854709 – via Google Books.

- ^ "High hopes for replica plane". BBC News. 10 October 2001.

- ^ "England and Wales Census, 1871". FamilySearch.org.

- ^ "England and Wales Census, 1881". FamilySearch.org.

- ^ Historic England. "STRINGFELLOW MONUMENT, APPROXIMATELY 65 METRES WEST OF CEMETERY MORTUARY CHAPELS, Chard Town (1297091)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "John Stringfellow and Powered Flight • Inventors and Inventions from Yorkshire • MyLearning". www.mylearning.org.

- ^ "John Stringfellow Should be Alongside Wright Brothers". 18 June 2020.

- ^ Royal Aeronautical Society#Henson & Stringfellow Lecture and Dinner

- Harald Penrose, An Ancient Air: A Biography of John Stringfellow of Chard, The Victorian Aeronautical Pioneer (Shrewsbury, England: Airlife Publishing, Ltd., 1988), 183p., illus. ISBN 1-85310-047-1