| Kakiemon elephants | |

|---|---|

on display in the museum | |

| Material | porcelain |

| Size | Height: 35.5 cm Width: 44 cm Length: 14.5 cm |

| Created | 1660-1690 Edo period |

| Place | Arita, Japan |

| Present location | Room 92-94, British Museum, London |

| Identification | 766883 |

| Registration | 1980,0325.1-2 |

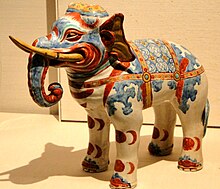

The Kakiemon elephants are a pair of 17th century Japanese porcelain figures of elephants in the British Museum. They were made by one of the Kakiemon potteries, which created the first enamelled porcelain in Japan,[1] and exported by the early Dutch East India Company. These figures are thought to have been made between 1660 and 1690 and are in the style known as Kakiemon. They were made near Arita, Saga on the Japanese island of Kyūshū at a time when elephants would not have been seen in Japan.[2]

Description

[edit]The figures are largely based on Asian elephants but differ slightly in some details. Like Dürer's Rhinoceros this is art based on the best information available. The artists who made these figures had never seen a real elephant and had to work from drawings and sketches; possibly from Buddhist sources.[3] They are made from enamelled porcelain, which would have been a new technology in Japan at the time they were made. Each elephant is 35.5 cm high, 44 cm long and 14.5 cm wide. The novel near-white glaze which is called 'nigoshide' was developed in this Japanese pottery in the seventeenth century.[4] 'Nigoshide' is known for its whiteness and is named after the residue that is left after washing rice.[5] The white ground is decorated with the additional characteristic coloured glazes of red, green, yellow and blue.[2]

Provenance

[edit]

These ceramics came from the pottery of Sakaida Kakiemon who lived from 1596 to 1666. He worked with Higashijima Tokuemon to create this now traditional type of pottery, which was copied by other factories in the area. Kakiemon's descendants continued this style of porcelain but it fell into disuse and it was revived by a twelfth generation descendant, Sakaida Shibonosuke.[1] Kakiemon ware was an important type of Japanese export porcelain, shipped to Europe by the Dutch East India Company between the ports of Imari and Amsterdam. This trade grew enormously in the late 17th century. England had tried to establish a 'factory' (that is, a trading post) in Japan in 1613 under an agreement between King James I and the shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada but the initiative was abandoned in 1623.

The elephants are now in the British Museum, as part of the collection donated by Sir Harry Garner.

Importance

[edit]The emergence of enamelled porcelain near Arita in Kyushu began Kakiemon-style decoration in overglazed coloured enamels. The success of the Japanese was due to the disruption of the Chinese Jingdezhen porcelain industry during the civil war at the transition between the Ming Dynasty and the Qing dynasty. In this brief period Chinese export porcelain largely dried up, and Japanese potters stepped in to fill the gap, including Kakiemon's new technique and style. These elephants are thought to have been made in 1660 to 1690. They would have been made by casting into moulds and the remains of broken elephant shaped moulds have been found in modern excavations at Arita.[3] Meissen porcelain, which was developed in the 18th century, is considered to have been strongly influenced by the Kakiemon Japanese imports.[4]

The milk-white glaze called 'nigoshide', developed by Kakiemon, was out of use by the end of the Edo period. However the technique was rediscovered in 1953 by Sakaida Kakiemon XII (1878–1963) and Sakaida Kakiemon XIII (1906–1982) and was declared a Japanese "Important Intangible Cultural Asset" in 1971. Kakiemon porcelain continued to be made under Sakaida Kakiemon XIV until his death in June 2013.[5]

There are few artefacts like this pair of elephants extant although there is a similar elephant (c.1680) in the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands and another in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.[3]

A History of the World in 100 Objects

[edit]This sculpture was featured in A History of the World in 100 Objects, a series of radio programmes that started in 2010 as a collaboration between the BBC and the British Museum.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Japan: Its History, Arts and Literature. Volume 8, Frank Brinkley, p.112, accessed September 2010

- ^ a b Kakiemon elephants, British Museum, accessed 6 September 2010

- ^ a b c Object of the Month November, Groningen Museum, accessed 6 September 2010

- ^ a b Japan encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric p.455, accessed 6 September 2010

- ^ a b Kakiemon Sakaida, ExploreJapaneseCeramics, accessed 7 September 2010

- ^ A History of the World in 100 Objects, BBC. accessed 5 September 2010