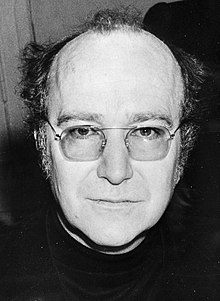

Klaus Croissant (24 May 1931 – 28 March 2002) was a lawyer of the Red Army Faction, later an East German spy and a political activist for Berlin's Alternative Liste für Demokratie und Umweltschutz and, after 1990, the PDS.

Croissant was shown by Kurt Rebmann, then Attorney General of Germany, "to have organized his cabinet the operational reserve of West German terrorism". A campaign against his imprisonment was organized in which, in particular, Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault took part. He was released on bail and absconded to France on 10 July 1977. He was apprehended in Paris on 30 September. He applied for political asylum but his plea was rejected by the court of criminal appeal of the Court of Appeal of Paris and an extradition order made on 16 November 1977 despite some protests in Germany, France and Italy. He was extradited to West Germany the following day. In a platform published in Le Monde on 2 November 1977, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari wrote:

Three things worry us immediately: the possibility that many German men of the left in an organized system of denouncement, see their life becoming intolerable in Germany, and are forced to leave their country. Conversely, the possibility that Croissant is delivered, returned to Germany where he risks the worst [Andreas Baader and his comrades had been found dead in their cells on October 18, 1977], or, simply expelled in a country of "choice" which would not accept him. Lastly, the prospect which whole Europe passes under this type of control claimed by Germany.[1]

He was sentenced to two-and-a-half years' imprisonment for supporting a designated terrorist organization. After his release, Croissant started to work for the Stasi, which registered him, in 1981, as Inoffizieller Mitarbeiter "IM Taler", Reg. Nr. XV/5231/81. His girlfriend, the taz-publisher and green member of the European Parliament Brigitte Heinrich, was led by Croissant to join his work for the Stasi till her death in 1987. In 1992, his collaboration with the Stasi was made public.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (2 November 1977) "The worst means of making Europe", Le Monde, p. 6. Included in Two Regimes of Madness: Interviews and Texts 1985-1995 (Semiotext(e), 2006), pp. 134–137

- ^ Klaus Marxen, Gerhard Werle (Hrsg.):Strafjustiz und DDR-Unrecht: Dokumentation. Spionage, Band 4, Walter de Gruyter, 2004, ISBN 978-3899490800, S. 19

Sources

[edit]- "Erinnerung an einen Freund oder Die Amsterdamer Gewissenserforschung" (Remembering a friend or researching conscience in Amsterdam)by Gaspard Dünkelsbühler in Fern und nah, Gesichter, Stimmen 1950 – 70, 2003

- Peter O. Chotjewitz: Mein Freund Klaus (My friend Klaus), Berlin 2007, Verbrecher Verlag, ISBN 978-3-935843-89-8