A library catalog (or library catalogue in British English) is a register of all bibliographic items found in a library or group of libraries, such as a network of libraries at several locations. A catalog for a group of libraries is also called a union catalog. A bibliographic item can be any information entity (e.g., books, computer files, graphics, realia, cartographic materials, etc.) that is considered library material (e.g., a single novel in an anthology), or a group of library materials (e.g., a trilogy), or linked from the catalog (e.g., a webpage) as far as it is relevant to the catalog and to the users (patrons) of the library.

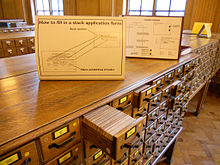

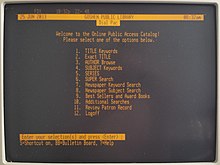

The card catalog was a familiar sight to library users for generations, but it has been effectively replaced by the online public access catalog (OPAC). Some still refer to the online catalog as a "card catalog".[2] Some libraries with OPAC access still have card catalogs on site, but these are now strictly a secondary resource and are seldom updated. Many libraries that retain their physical card catalog will post a sign advising the last year that the card catalog was updated. Some libraries have eliminated their card catalog in favor of the OPAC for the purpose of saving space for other use, such as additional shelving.

The largest international library catalog in the world is the WorldCat union catalog managed by the non-profit library cooperative OCLC.[3] In January 2021, WorldCat had over half a billion catalog records and three billion library holdings.[4]

Goal

[edit]

Antonio Genesio Maria Panizzi in 1841[5] and Charles Ammi Cutter in 1876[6] undertook pioneering work in the definition of early cataloging rule sets formulated according to theoretical models. Cutter made an explicit statement regarding the objectives of a bibliographic system in his Rules for a Printed Dictionary Catalog.[7] According to Cutter, those objectives were

1. to enable a person to find a book of which any of the following is known (Identifying objective):

- the author

- the title

- the subject

- the date of publication

2. to show what the library has (Collocating objective)

- by a given author

- on a given subject

- in a given kind of literature

3. to assist in the choice of a book (Evaluating objective)

- as to its edition (bibliographically)

- as to its character (literary or topical)

These objectives can still be recognized in more modern definitions[8] formulated throughout the 20th century.

Other influential pioneers in this area were Shiyali Ramamrita Ranganathan and Seymour Lubetzky.[9]

Cutter's objectives were revised by Lubetzky and the Conference on Cataloging Principles (CCP) in Paris in 1960/1961, resulting in the Paris Principles (PP).

A more recent attempt to describe a library catalog's functions was made in 1998 with Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR), which defines four user tasks: find, identify, select, and obtain.[10]

A catalog helps to serve as an inventory or bookkeeping of the library's contents. If an item is not found in the catalog, the user may continue their search at another library.

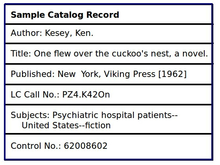

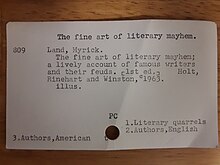

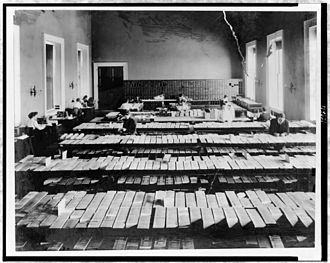

Card

[edit]A catalog card is an individual entry in a library catalog containing bibliographic information, including the author's name, title, and location. Eventually the mechanization of the modern era brought the efficiencies of card catalogs. It was around 1780 that the first card catalog appeared in Vienna. It solved the problems of the structural catalogs in marble and clay from ancient times and the later codex—handwritten and bound—catalogs that were manifestly inflexible and presented high costs in editing to reflect a changing collection.[11] The first cards may have been French playing cards, which in the 1700s were blank on one side.[12]

In November 1789, during the dechristianization of France during the French Revolution, the process of collecting all books from religious houses was initiated. Using these books in a new system of public libraries included an inventory of all books. The backs of the playing cards contained the bibliographic information for each book and this inventory became known as the "French Cataloging Code of 1791".[13]

English inventor Francis Ronalds began using a catalog of cards to manage his growing book collection around 1815, which has been denoted as the first practical use of the system.[14][15] In the mid-1800s, Natale Battezzati, an Italian publisher, developed a card system for booksellers in which cards represented authors, titles and subjects. Very shortly afterward, Melvil Dewey and other American librarians began to champion the card catalog because of its great expandability. In some libraries books were cataloged based on the size of the book while other libraries organized based only on the author's name.[16] This made finding a book difficult.

The first issue of Library Journal, the official publication of the American Library Association (ALA), made clear that the most pressing issues facing libraries were the lack of a standardized catalog and an agency to administer a centralized catalog. Responding to the standardization matter, the ALA formed a committee that quickly recommended the 2-by-5-inch (5 cm × 13 cm) "Harvard College-size" cards as used at Harvard and the Boston Athenaeum. It also suggested that a larger card, approximately 3 by 5 inches (8 cm × 13 cm), would be preferable. By the end of the nineteenth century, the bigger card won out, mainly to the fact that the 3-by-5-inch (8 cm × 13 cm) card was already the "postal size" used for postcards.

Melvil Dewey saw well beyond the importance of standardized cards and sought to outfit virtually all facets of library operations. To the end he established a Supplies Department as part of the ALA, later to become a stand-alone company renamed the Library Bureau. In one of its early distribution catalogs, the bureau pointed out that "no other business had been organized with the definite purpose of supplying libraries". With a focus on machine-cut index cards and the trays and cabinets to contain them, the Library Bureau became a veritable furniture store, selling tables, chairs, shelves and display cases, as well as date stamps, newspaper holders, hole punchers, paper weights, and virtually anything else a library could possibly need. With this one-stop shopping service, Dewey left an enduring mark on libraries across the country. Uniformity spread from library to library.[17]

Dewey and others devised a system where books were organized by subject, then alphabetized based on the author's name. Each book was assigned a call number which identified the subject and location, with a decimal point dividing different sections of the call number. The call number on the card matched a number written on the spine of each book.[16] In 1860, Ezra Abbot began designing a card catalog that was easily accessible and secure for keeping the cards in order; he managed this by placing the cards on edge between two wooden blocks. He published his findings in the annual report of the library for 1863 and they were adopted by many American libraries.[13]

Work on the catalog began in 1862 and within the first year, 35,762 catalog cards had been created. Catalog cards were 2 by 5 inches (5 cm × 13 cm); the Harvard College size. One of the first acts of the newly formed American Library Association in 1908 was to set standards for the size of the cards used in American libraries, thus making their manufacture and the manufacture of cabinets, uniform.[12] OCLC, major supplier of catalog cards, printed the last one in October 2015.[18]

In a physical catalog, the information about each item is on a separate card, which is placed in order in the catalog drawer depending on the type of record. If it was a non-fiction record, Charles A. Cutter's classification system would help the patron find the book they wanted in a quick fashion. Cutter's classification system is as follows:[19]

- A: encyclopedias, periodicals, society publications

- B–D: philosophy, psychology, religion

- E–G: biography, history, geography, travels

- H–K: social sciences, law

- L–T: science, technology

- X–Z: philology, book arts, bibliography

Types

[edit]

Traditionally, there are the following types of catalog:

- Author catalog: a formal catalog, sorted alphabetically according to the names of authors, editors, illustrators, etc.

- Subject catalog: a catalog that sorted based on the Subject.

- Title catalog: a formal catalog, sorted alphabetically according to the article of the entries.

- Dictionary catalog: a catalog in which all entries (author, title, subject, series) are interfiled in a single alphabetical order. This was a widespread form of card catalog in North American libraries prior to the introduction of the computer-based catalog.[20]

- Keyword catalog: a subject catalog, sorted alphabetically according to some system of keywords.

- Mixed alphabetic catalog forms: sometimes, one finds a mixed author / title, or an author / title / keyword catalog.

- Systematic catalog: a subject catalog, sorted according to some systematic subdivision of subjects. Also called a Classified catalog.

- Shelf list catalog: a formal catalog with entries sorted in the same order as bibliographic items are shelved. This catalog may also serve as the primary inventory for the library.

History

[edit]

The earliest librarians created rules for how to record the details of the catalog. By 700 BCE the Assyrians followed the rules set down by the Babylonians. The seventh century BCE Babylonian Library of Ashurbanipal was led by the librarian Ibnissaru who prescribed a catalog of clay tablets by subject. Subject catalogs were the rule of the day, and author catalogs were unknown at that time. The frequent use of subject-only catalogs hints that there was a code of practice among early catalog librarians and that they followed some set of rules for subject assignment and the recording of the details of each item. These rules created efficiency through consistency—the catalog librarian knew how to record each item without reinventing the rules each time, and the reader knew what to expect with each visit. The task of recording the contents of libraries is more than an instinct or a compulsive tic exercised by librarians; it began as a way to broadcast to readers what is available among the stacks of materials. The tradition of open stacks of printed books is paradigmatic to modern American library users, but ancient libraries featured stacks of clay or prepaper scrolls that resisted browsing.[citation needed]

As librarian, Gottfried van Swieten introduced the world's first card catalog (1780) as the Prefect of the Imperial Library, Austria.[11]

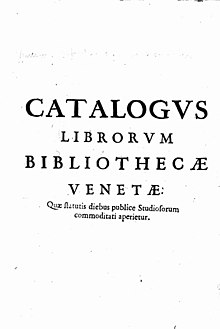

During the early modern period, libraries were organized through the direction of the librarian in charge. There was no universal method, so some books were organized by language or book material, for example, but most scholarly libraries had recognizable categories (like philosophy, saints, mathematics). The first library to list titles alphabetically under each subject was the Sorbonne library in Paris. Library catalogs originated as manuscript lists, arranged by format (folio, quarto, etc.) or in a rough alphabetical arrangement by author. Before printing, librarians had to enter new acquisitions into the margins of the catalog list until a new one was created. Because of the nature of creating texts at this time, most catalogs were not able to keep up with new acquisitions.[21]

When the printing press became well-established, strict cataloging became necessary because of the influx of printed materials. Printed catalogs, sometimes called dictionary catalogs, began to be published in the early modern period and enabled scholars outside a library to gain an idea of its contents.[22] Copies of these in the library itself would sometimes be interleaved with blank leaves on which additions could be recorded, or bound as guardbooks in which slips of paper were bound in for new entries. Slips could also be kept loose in cardboard or tin boxes, stored on shelves. The first card catalogs appeared in the late 19th century after the standardization of the 5 in. x 3 in. card for personal filing systems, enabling much more flexibility, and toward the end of the 20th century the online public access catalog was developed (see below). These gradually became more common as some libraries progressively abandoned such other catalog formats as paper slips (either loose or in sheaf catalog form), and guardbooks. The beginning of the Library of Congress's catalog card service in 1911 led to the use of these cards in the majority of American libraries. An equivalent scheme in the United Kingdom was operated by the British National Bibliography from 1956[23] and was subscribed to by many public and other libraries.

- c. Seventh century BCE, the royal Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh had 30,000 clay tablets, in several languages, organized according to shape and separated by content. Assurbanipal sent scribes to transcribe works in other libraries within the kingdom.[24]

- c. Third century BCE, Pinakes by Callimachus at the Library of Alexandria was arguably the first library catalog.

- 9th century: Libraries of Carolingian Schools and monasteries employ library catalog system to organize and loan out books.[25][26][27]

- c. 10th century: The Persian city of Shiraz's library had over 300 rooms and thorough catalogs to help locate texts these were kept in the storage chambers of the library and they covered every topic imaginable.[28]

- c. 1246: Library at Amiens Cathedral in France uses call numbers associated with the location of books.[29]

- c. 1542–1605: The Mughul emperor Akbar was a warrior, sportsman, and famous cataloger. He organized a catalog of the Imperial Library's 24,000 texts, and he did most of the classifying himself.[30]

- 1595: Nomenclator of Leiden University Library appears, the first printed catalog of an institutional library.

- Renaissance Era: In Paris, France The Sorbonne Library was one of the first libraries to list titles alphabetically based on the subject they happened to fall under. This became a new organization method for catalogs.[31]

- Early 1600s: Sir Thomas Bodley divided cataloging into three different categories. History, poesy, and philosophy.[32]

- 1674: Thomas Hyde's catalog for the Bodleian Library.

- 1791: The French Cataloging Code of 1791[33]

- 1815: Thomas Jefferson sells his personal library to the US government to establish the Library of Congress. He had organized his library by adapting Francis Bacon's organization of knowledge, specifically using Memory, Reason, and Imagination as his three areas, which were then broken down into 44 subdivisions.

- 1874/1886: Breslauer Instructionen (English: Wroclaw instructions) by Karl Dziatzko

- 1899: Preußische Instruktionen (PI) (English: Prussian instructions) for scientific libraries in German-speaking countries and beyond

- 1932: DIN 1505

- 1938: Berliner Anweisungen (BA) (English: Berlin instructions) for public libraries in Germany

- 1961: Paris Principles (PP), internationally agreed upon principles for cataloging

- 1967: Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR)

- 1971: International Standard Bibliographic Description (ISBD)

- 1976/1977: Regeln für die alphabetische Katalogisierung (RAK) (English: Rules for alphabetical cataloging) in Germany and Austria

More about the early history of library catalogs has been collected in 1956 by Strout.[34]

Sorting

[edit]

In a title catalog, one can distinguish two sort orders:

- In the grammatical sort order (used mainly in older catalogs), the most important word of the title is the first sort term. The importance of a word is measured by grammatical rules; for example, the first noun may be defined to be the most important word.

- In the mechanical sort order, the first word of the title is the first sort term. Most new catalogs use this scheme, but still include a trace of the grammatical sort order: they neglect an article (The, A, etc.) at the beginning of the title.

The grammatical sort order has the advantage that often, the most important word of the title is also a good keyword (question 3), and it is the word most users remember first when their memory is incomplete. To its disadvantage, many elaborate grammatical rules are needed, so many users may only search with help from a librarian.

In some catalogs, persons' names are standardized (i. e., the name of the person is always cataloged and sorted in a standard form) even if it appears differently in the library material. This standardization is achieved by a process called authority control. Simply put, authority control is defined as the establishment and maintenance of consistent forms of terms – such as names, subjects, and titles – to be used as headings in bibliographic records.[35] An advantage of the authority control is that it is easier to answer question 2 (Which works of some author does the library have?). On the other hand, it may be more difficult to answer question 1 (Does the library have some specific material?) if the material spells the author in a peculiar variant. For the cataloger, it may incur too much work to check whether Smith, J. is Smith, John or Smith, Jack.

For some works, even the title can be standardized. The technical term for this is uniform title. For example, translations and re-editions are sometimes sorted under their original title. In many catalogs, parts of the Bible are sorted under the standard name of the book(s) they contain. The plays of William Shakespeare are another frequently cited example of the role played by a uniform title in the library catalog.

Many complications about alphabetic sorting of entries arise. Some examples:

- Some languages know sorting conventions that differ from the language of the catalog. For example, some Dutch catalogs sort IJ as Y. Should an English catalog follow this suit? And should a Dutch catalog sort non-Dutch words the same way? There are also pseudo-ligatures which sometimes come at the beginning of a word, such as Œdipus. See also Collation and Locale (computer software).

- Some titles contain numbers, for example 2001: A Space Odyssey. Should they be sorted as numbers, or spelled out as Two thousand and one? (Book-titles that begin with non-numeral-non-alphabetic glyphs such as #1 are similarly very difficult. Books which have diacritics in the first letter are a similar but far-more-common problem; casefolding of the title is standard, but stripping the diacritics off can change the meaning of the words.)

- de Balzac, Honoré or Balzac, Honoré de? Ortega y Gasset, José or Gasset, José Ortega y? (In the first example, "de Balzac" is the legal and cultural last name; splitting it apart would be the equivalent of listing a book about tennis under "-enroe, John Mac-" for instance. In the second example, culturally and legally the lastname is "Ortega y Gasset" which is sometimes shortened to simply "Ortega" as the masculine lastname; again, splitting is culturally incorrect by the standards of the culture of the author, but defies the normal understanding of what a 'last name' is—i.e. the final word in the ordered list of names that define a person—in cultures where multi-word-lastnames are rare. See also authors such as Sun Tzu, where in the author's culture the surname is traditionally printed first, and thus the 'last name' in terms of order is in fact the person's first-name culturally.)

Classification

[edit]In a subject catalog, one has to decide on which classification system to use. The cataloger will select appropriate subject headings for the bibliographic item and a unique classification number (sometimes known as a "call number") which is used not only for identification but also for the purposes of shelving, placing items with similar subjects near one another, which aids in browsing by library users, who are thus often able to take advantage of serendipity in their search process.

Online

[edit]

Online cataloging, through such systems as the Dynix software[36] developed in 1983 and used widely through the late 1990s,[37] has greatly enhanced the usability of catalogs, thanks to the rise of MARC standards (an acronym for MAchine Readable Cataloging) in the 1960s.[38]

Rules governing the creation of MARC catalog records include not only formal cataloging rules such as Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, second edition (AACR2),[39] Resource Description and Access (RDA)[40] but also rules specific to MARC, available from both the U.S. Library of Congress and from OCLC, which builds and maintains WorldCat.[41]

MARC was originally used to automate the creation of physical catalog cards, but its use evolved into direct access to the MARC computer files during the search process.[42]

OPACs have enhanced usability over traditional card formats because:[43]

- The online catalog does not need to be sorted statically; the user can choose author, title, keyword, or systematic order dynamically.

- Most online catalogs allow searching for any word in a title or other field, increasing the ways to find a record.

- Many online catalogs allow links between several variants of an author's name.

- The elimination of paper cards has made the information more accessible to many people with disabilities, such as the visually impaired, wheelchair users, and those who suffer from mold allergies or other paper- or building-related problems.

- Physical storage space is considerably reduced.

- Updates are significantly more efficient.

See also

[edit]- Cataloging – Process of creating meta-data for information resources to include in a catalog database

- International Standard Bibliographic Description – human-readable standard for description of bibliographic resources

- Social cataloging application – collaborative cataloging of literature based in web

References

[edit]- ^ Highsmith, Carol M. (2009), Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress in the Thomas Jefferson Building, archived from the original on 2019-06-15, retrieved 2019-04-20

- ^ For example, the website of the Childress Public Library in Childress, Texas refers to its online catalog as a "card catalog": "Online Card Catalog | Childress Public Library". harringtonlc.org. Archived from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 2020-09-17. Another example of the term "card catalog" used to refer to an online catalog is in an instructional presentation produced by the Hayner Public Library District, which serves townships around Alton, Illinois: Cordes, Mary. "Searching the Card Catalog and Managing Your Library Account Online" (PDF). www.haynerlibrary.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-10-07. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ Oswald, Godfrey (2017). "Largest unified international library catalog". Library world records (3rd ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 291. ISBN 9781476667775. OCLC 959650095.

- ^ "Inside WorldCat". OCLC. Archived from the original on 2017-01-30. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ Panizzi, Antonio "Anthony" Genesio Maria (1841). "Rules for the Compilation of the Catalogue". Catalogue of Printed Books in the British Museum. Vol. 1. London, UK. pp. V–IX.

- ^ Cutter, Charles (1876). Rules for a dictionary catalog. United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ Cutter, Charles Ammi (1876). Public Libraries in the United States of America their History, Condition, and Management.

- ^ "What Should Catalogs Do? / Eversberg". 2016-03-05. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ Denton, William (2007). "FRBR and the History of Cataloging". In Taylor, Arlene G. (ed.). Understanding FRBR. What it is and how it will affect our Retrieval Tools. Westport: Libraries Unlimited. pp. 35–57 [35–49]. hdl:10315/1250.

- ^ Hider, Philip (2017-02-17). "A Critique of the FRBR User Tasks and Their Modifications". Cataloging & Classification Quarterly. 55 (2): 55–74. doi:10.1080/01639374.2016.1254698. ISSN 0163-9374. S2CID 63488662.

- ^ a b "1780: The Oldest Card Catalogue". Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Archived from the original on 2022-03-02. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ a b Krajewski, M. (2011). Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548–1929. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262015899.[page needed]

- ^ a b Nix, L. T. (21 January 2009). "Evolution of the Library Card Catalog". The Library History Buff. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ James, M. S. (1902). "The Progress of the Modern Card Catalog Principle". Public Libraries. 7 (187): 185–189.

- ^ Ronalds, B. F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: ICP. ISBN 9781783269174.

- ^ a b Schifman, J. (11 February 2016). "How the Humble Index Card Foresaw the Internet". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ LOC (2017). The Card Catalog: Books, Cards, and Literary Treasures. San Francisco: Chronicle. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9781452145402.

- ^ "OCLC prints last library catalog cards". Library, Archive & Museum. Online Computer Library Center. 1 October 2015. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Murray, S. A. F. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse. p. 205. ISBN 9781602397064.

- ^ Wiegand, Wayne; Davis, Donald G. Jr. (1994). Encyclopedia of Library History. Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 605–606. ISBN 978-0824057879.

- ^ Murray, pp. 88–89.

- ^ E.g. (1) Radcliffe, John Bibliotheca chethamensis: Bibliothecae publicae Mancuniensis ab Humfredo Chetham, armigero fundatae catalogus, exhibens libros in varias classas pro varietate argumenti distributos; [begun by John Radcliffe, continued by Thomas Jones]. 5 vols. Mancuni: Harrop, 1791–1863. (2) Wright, C. T. Hagberg & Purnell, C. J. Catalogue of the London Library, St. James's Square, London. 10 vols. London, 1913–55. Includes: Supplement: 1913–20. 1920. Supplement: 1920–28. 1929. Supplement: 1928–53. 1953 (in 2 vols). Subject index: (Vol. 1). 1909. Vol. 2: Additions, 1909–22. Vol. 3: Additions, 1923–38. 1938. Vol. 4: (Additions), 1938–53. 1955.

- ^ Walford, A. J., ed. (1981) Walford's Concise Guide to Reference Material. London: Library Association; p. 6

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-61608-453-0.

- ^ Schutz, Herbert (2004). The Carolingians in Central Europe, Their History, Arts, and Architecture: A Cultural History of Central Europe, 750–900. BRILL. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-90-04-13149-1.

- ^ Colish, Marcia L. (1999). Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition, 400–1400. Yale University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-300-07852-7.

- ^ Lerner, Fred (2001-02-01). Story of Libraries: From the Invention of Writing to the Computer Age. A&C Black. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8264-1325-3.

- ^ Murray, p. 56

- ^ Joachim, Martin D. (2003). Historical Aspects of Cataloging and Classification. Haworth Information Press. p. 460. ISBN 978-0-7890-1981-3.

- ^ Murray, pp. 104–105

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-61608-453-0.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-61608-453-0.

- ^ "Origins of the Card Catalog – LIS415OL History Encyclopedia". 2012-12-15. Archived from the original on 2012-12-15.

- ^ Strout, R.F. (1956). "The development of the catalog and cataloging codes" (PDF). Library Quarterly. 26 (4): 254–75. doi:10.1086/618341. S2CID 144623376. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02.

- ^ "Authority Control". Dictionary.com Unabridged. 2017.

- ^ Dunsire, G.; Pinder, C. (1991). "Dynix, automation and development at Napier Polytechnic". Program: Electronic Library and Information Systems. 25 (2): 91. doi:10.1108/eb047078.

- ^ Automation Systems Installed Archived January 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Counting by Library organizations.

- ^ Coyle, Karen (2011-07-25). "MARC21 as Data: A Start". The Code4Lib Journal (14). Archived from the original on 2019-05-23. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "AACR2". www.aacr2.org. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "RDA Toolkit". Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ "WorldCat facts and statistics". Online Computer Library Center. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-12-05. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ^ Avram, Henriette D. (1975). MARC, its history and implications. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 29–30. hdl:2027/mdp.39015034388556. ISBN 978-0844401768.

- ^ Husain, Rashid; Ansari, Mehtab Alam (March 2006). "From Card Catalogue to Web OPACs". DESIDOC Bulletin of Information Technology. 26 (2): 41–47. doi:10.14429/dbit.26.2.3679. Archived from the original on 2016-02-07. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

Sources

[edit]- Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Chicago: Skypoint Publishing. ISBN 978-1602397064.

Further reading

[edit]- Chan, Lois Mai (2007). Cataloging and Classification: An Introduction (3rd ed.). Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810860001. OCLC 124031949.

- Hanson, James C. M.; et al. (1908). Catalog Rules: Author and Title Entries (American ed.). Chicago: American Library Association. OCLC 1466843.

- Joudrey, Daniel N.; Taylor, Arlene G.; Miller, David P. (2015). Introduction to Cataloging and Classification (11th ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited/ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-856-4. OCLC 911180115.

- Library of Congress (2017). The Card Catalog: Books, Cards, and Literary Treasures. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1452145402. OCLC 953599088.

- Svenonius, Elaine (2000). The Intellectual Foundation of Information Organization. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262194334. OCLC 42040872.

- Taylor, Archer (1986). Book Catalogues: Their Varieties and Uses. Introductions, corrections and additions by W. P. Barlow, Jr. (2nd ed.). New York: Frederic C. Beil. ISBN 978-0913720660. OCLC 14931714. Previous edition: Taylor, Archer (1957). Book Catalogues: Their Varieties and Uses (1st ed.). Chicago: Newberry Library. OCLC 1705207.